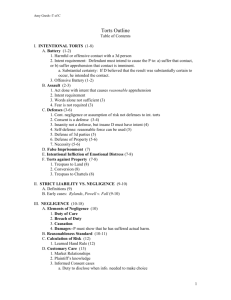

TORTS OUTLINE - NYU School of Law

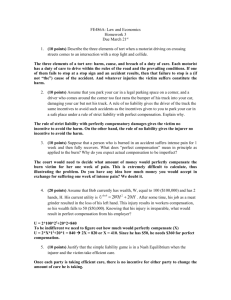

advertisement