Online-Oncampus: The best of both worlds in a `blended learning

advertisement

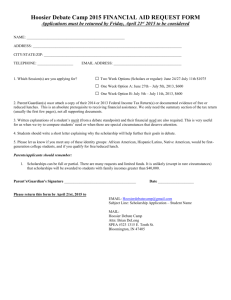

Online-oncampus: the best of both worlds in a ‘blended learning’ project. Darrall Thompson University of Technology, Sydney darrall.thompson@uts.edu.au Abstract: (word count 249) The early economic imperative that funded ill-considered approaches to e-learning is maturing to the appropriate use of blended online and face-to-face methodologies. This paper introduces an exemplar of one such project aimed at leveraging the best of both worlds in an undergraduate design course with ninety second year students. Scenario from the online debate project brief: ‘Imagine we have just been joined on our UTSOnline website by eighteen famous typographers / artists / designers. They represent strong views about the ‘self-expressive’ versus the ‘functional’ approaches to typography and design. Some of them are in disagreement and want to have a discussion / argument about their approaches. However quite a few of them are dead and the others not here in Australia so we have arranged for this to happen using your tutorial groups as champions of their points of view and philosophy.’. A final face-to-face ‘first-person’ debate in the lecture theatre gave release to the tension between opposing groups in dramatic creative portrayals of 18 ‘individuals’ exploring their design philosophy and practice. This blended learning group-based project was run online by one lecturer with two thirty minute oncampus briefing sessions. Criterion-based and self and peer assessment were conducted with two online systems designed and developed at UTS and outlined in this paper. The depth and dimension of student learning through this project are described using samples of evidence from a research case study which included questionnaire surveys, focus groups, analysis of online data and video of the faceto-face presentation. Keywords: Online, Assessment, Groupwork, Attributes, Blended, Learning, Design Paper: (word count 3951 including refs) Introduction ‘... What the learned world tends to offer is one second-hand scrap of information illustrating ideas derived from another second-hand scrap of information. The secondhandedness of the learned world is the secret of its mediocrity.’ (Whitehead 1929:74) The last thing we need in universities is a mediocre experience in which the surface engagement of students may lead to boredom and a passive ‘acquisition’ of inert knowledge. The teaching of design history at university level has too-often fallen into this category using a lecture ‘delivery’ metaphor, with minimal reflection about the degree or quality of student learning achieved. In the BDesign Visual Communication program at UTS a new approach to a design history subject was developed by Adjunct Professor Jenny Wilson. During the last four years I have developed an online / oncampus ‘blended learning’ version which extends the themes explored through this subject and endeavours to enhance the depth of student engagement and the quality of their learning. In an endeavour to underpin this new approach with sound educational principles, I took the opportunity of a six month secondment to the UTS Centre for Learning and Teaching (now Institute for Interactive Media and Learning). Through my studies in educational theory and research it became clear that there was an unreconciled gap between the theorists and the practitioners in higher education. For example Ramsden (1992: ix) complained that: ‘the busy lecturer or head of department has no time to acquire an understanding of the subject of education’. “Don’t give me theory: just give me something that works” is a plea that there is every temptation to answer.’ The translation of theory into practical solutions could be considered not to be the responsibility of pure theorists and researchers, but perhaps of those who often work closely with them in educational development units. However, staff in these units are often remote from faculties, and with no funds allocated to develop the specific solutions needed. In the case of design education there appeared to be little application of educational theory to the teaching context, and a great need for ‘something that works’. Stimulated by the possibilities, and with a background in interface design, I became involved with the design of two web-based software applications. These two online assessment ‘systems’ and the pedagogy embedded in them were specifically aimed at the assessment of group work and graduate attributes, and became integral to the learning design of the new design history subject. The idea behind this online assessment approach was to facilitate good teaching and learning strategies with tools which reduced staff workload and enhanced student learning. Extracts from my recent research case study are used in this paper to highlight particular successes and areas for further study. The site for research - an undergraduate course of study The BDesign Visual Communication is a four-year honours program, which commands the highest UAI (University Admissions Index) for a design course in Australia. The course prepares students for employment in the burgeoning publishing, web, TV broadcast, film and advertising industries including many government and non-government organisations and corporations who have their own ‘in-house’ design departments. The four years of the course have general themes: 1st year- Introductory; 2nd year- Experimental; 3rd yearProfessional; 4th year- Self Directed. The case study for this research was done at the beginning of the 2nd year with 90 students in their ‘experimental’ stage. The subject ‘Introduction to Typography’ had been designed to accommodate the learning task for this case study. It was referred to as the ‘Online Debate’ project and sat between two other learning tasks in the subject: Task 1. - 30% ‘Thamus’ - a poster design calling for detailed typographic layout to enhance meanings within the text, in combination with complementary self generated imagery; Task 2. - 20% The Online Debate. (to be described in detail later in this paper); Task 3. - 50% Font Design, the design of an original typeface from concept to a complete finished computer drawn font. The overall 13 week subject was run on the same day each week with students attending a one-hour lecture, followed by a two-hour computer tutorial, followed by a two-hour practical studio class. There was no tutorial or class time allocated to Task 2 The Online Debate, but there were two thirty minute briefing sessions and a two-hour live presentation by students at the end of the project in week 10. Features of the ‘learning design’ for the research case study There can be no adequate technical education which is not liberal, and no liberal education which is not technical; that is, no education which does not impart both technique and intellectual vision. .... This intimate union of practice and theory aids both. The intellect does not work best in a vacuum’. (Whitehead 1929:79) The Online Debate project was the only group task alongside two other individual tasks and involved students in extensive research about other designers’ works whilst they were actively engaged in producing individual design work during computer tutorials and studio classes. Students were randomly formed into 18 ‘learning groups’ of 5 students each at the beginning of semester as a method for managing tutorial and studio sessions throughout the thirteen week period. The online debate project ran whilst the other two tasks were being undertaken and spanned a period of eight weeks in the middle of the semester. There were two online submission deadlines on Sundays at midnight to stimulate online activity from home and also to avoid other interim deadlines within the course. The following extract from the ‘Online Debate briefing document’ is part of the explanation students received through UTSOnline (a customised version of Blackboard Courseinfo learning management software): ‘Scenario: Imagine we have just been joined on our UTSOnline website by eighteen famous typographers / artists / designers. They represent strong views about the ‘expressive’ versus the ‘functional’ approaches to typography and design. Some of them are in disagreement and want to have a discussion / argument about their approaches. However quite a few of them are dead and the others not here in Australia so we have arranged for this to happen using your tutorial groups as champions of their points of view and philosophy.’ (extract from the online debate project brief 2003). In order to promote a deep engagement with the learning task, students were challenged to ‘become’ the typographer or designer their group had been given, or at least to temporarily adopt their views and philosophies. This was encouraged using a number of online / oncampus features and events built into the learning design and integrated with the online systems used: a) a photograph of each learning group was posted online with their new ‘persona’s’ name at the time when the groups needed to identify and challenge the group opposing their position, b) an instruction was given in the brief that all online written submissions (and the live debate at the end) had to be written or spoken in ‘first person’ style; c) an instruction that the group had to research their given persona through the following ‘holistic’ research questions which I designed to broaden the information that would form the basis for their online debate submissions: The ‘Five-Dimensional’ Research Questions: 1. Propositions - What did they believe and what were they trying to do? 2. Influences and connections - Where did they draw there influences from and who were they connected to eg. artistic movements etc? 3. Principles and ways of working - How did they go about their work and what did they consider important in the way it was done ? 4. Character / Personality - What were they like as a person ? 5. Facts and Figures - What interesting facts can you find as well as the usual birth / death / education that is available. (Guided research questions from the Online Debate brief 2003) d) The SPARK self and peer assessment system for group work was explained showing examples and student comments. Students had access to the system and were encouraged to question the criteria upon which they would rate themselves and their colleagues at the end of the learning task. e) Students were asked to position (X) their given individual with reference to a ‘spectrum’ ranging from ‘functional’, ‘problem-solving’ design at one end to ‘expressive’, ‘artistic’ design at the other. FUNCTIONAL <--------------------------------------------------(X)-------> EXPRESSIVE f) Students were encouraged to be creative in costume and drama in making their points in the live debate at the end of the task. Assessment systems used for the Online Debate learning task 'Assessment is the single most powerful influence on learning in formal courses and, if not designed well, can easily undermine the positive features of an important strategy in the repertoire of teaching and learning approaches' (Boud, Cohen et al. 2001:67) It is clear that the careful contextualisation and motivational features described so far could be undermined by poor assessment design. For example, in my previous attempts using paper-based self and peer assessment for group work projects, a number of serious problems rendered the process untenable: ‘The Identified Problems of Paper-based systems In summary the problems identified through the use of paper-based systems in two design subjects were: • lack of time to reflect and change ones ratings after the end of the project. • small range of criteria did not address contributions leaving graduate attributes non-specific or hidden. • lack of choice where anonymity is concerned - arising from the practicality of assessment happening when all the students are together. • the complexities of calculating the contribution of multiple feedback from each group member across a range of criteria. • lecturer's avoidance of comprehensive criteria due to the onerous task of calculating a conversion of the group mark into individual marks. • collusion, and the students' adoption of a surface approach to the whole system, undermining the educational value of group work. • lack of scalability when extra groups and larger numbers of students are involved • difficulty of distribution and collection of assessment particularly with part time courses and lecturers.’ (Thompson 2002: 365) SPARK (Self and Peer Assessment Resource Kit) As a result of my recent research case study it is my view that these problems can be solved through the careful application of an open source web-based solution called SPARK (Self and Peer Assessment Resource Kit), developed with a team of colleagues at UTS (http://www.educ.dab.uts.edu.au/darrall/SPARKsite/). Since 2000 there have been a number of case studies highlighting the success of this online approach and this paper reinforces those findings. The results are discussed later in this paper with extracts from my research case study based on the online debate project. Figure 1 SPARK rating process showing criteria and rating scale The factors produced from these SPARK ratings were then used to calculate individual marks based on each group member’s contribution to the group mark given by the lecturer. Online Criteria Based Assessment Software (O.C.B.A) Apart from the group work aspect of the project there were two assessment criteria used t assess the group mark that covered all three parts of the student groups’ submissions (Opening Statements, Challenging Statements and Live Debate). The criteria related to two subject learning objectives in the categories of Research and Process: RESEARCH - Depth of research in substantiating the points of view, and PROCESS - The cogency with which arguments and rebuttals are developed. In assessment throughout the four years of the BDesign Visual Communication degree there is a consistent set of criteria categories which forms the basis of an approach to ensuring the development of necessary graduate attributes. The five categories are: RESEARCH, CONCEPT, COMMUNICATION, PROCESS, PROFESSIONALISM. As part of my research I designed Online Criteria-based Assessment software to gather multiple assessments from a range of learning tasks and assessment criteria, and give feedback to students about their progress in these specific graduate attribute areas. A beta version was used in the Online Debate subject to mark and give feedback on this task (together with the two other tasks in the subject). Staff were able to assess both on and off campus and students were able to log on to receive their group’s assessment and feedback online. Research case study data from the online debate project Figure 2 Data sets collected in the research case study These five data sets together with transcripts of staff interviews were analysed to discover areas of student learning with specific reference to group work and graduate attributes. The following extracts serve to give a brief snapshot of some of the data which will be fully published in my research masters mid. 2004. As an indicator of the students’ engagement in the task, the online access on weekends Table 1 shows that the Saturday and Sunday hits constitute about a quarter of all logon statistics. Analysis of the data revealed that 33.2% of the weekday accesses occurred outside the normal undergraduate class time of 9am to 5pm. This is an extensive use of home access not driven by workload pressures as questionnaire data indicated that 87% of students did not find this learning task an onerous undertaking. Table 1 Access to UTSOnline showing extensive usage at weekends User Accesses Per Day of the Week (8 wk period) Day of Week Hits Saturday 1258 Sunday 2516 Monday 1736 Tuesday 1538 Wednesday 776 Thursday 5751 Friday 1755 Total 15330 The hits were distributed amongst students as follows: One student had 0 hits; Another 5 students had less than 50 hits; 23 had between 50 and 100 hits; 57 students exceeded 100 hits; One student had 552 hits. Percent 8.2 16.41 11.32 10.03 5.06 37.51 11.44 100 These figures show a strong participation rate for the majority of students. The figures also show that six students were able to complete the project with comparatively minimal personal online engagement, presumably assisted by their peers. In studying the 36,000 words of online written submissions there was ample evidence of the groups’ participation levels in the degree to which they adopted the position of their given designer/typographer. Their language used in submissions also displayed levels of learning at the higher ‘extended abstract’ end of Biggs’ (1991) SOLO (Structure of Observed Learning Outcomes) Taxonomy. The following quote is extracted from a ‘challenging statement’ from one of the groups who identified their designer/typographer as positioned at the functional end of the design spectrum (Functional > Expressive): ‘Why, Neville, do you blatantly break all conventions, going out of your way to be different purely for the sake of it? You say your work ‘typifies your sense of self, and it is through typography that your identity is personified.’ A nice idea, but where does your viewer enter the equation? As Bayer rightly stated, typography is ‘a service art not a fine art’. It is there for both the designer and the viewer, a means by which a message is not only given but also received and understood. To use typographic design in a way that is expressive to the point of inhibiting the viewer from grasping the original meaning is surely nothing more than egotistical self-indulgence. Be bold, be daring, but remember your audience!’ (from the student group ‘being’ Laszlo Moholy-Nagy to the group ‘being’ Neville Brody, online challenging statement 27.4.03) As an example from the expressive end of the spectrum the following quote is part of the Neville Brody group’s response to the Laszlo group: ‘I do not agree with your philosophy of uniform lettering and elimination to detail. Type must be visually engaging in order to attract and maintain attention. With expressive type, the end interpretation is always left up to the audience, and to the designer, successful design is one that creates a mixture of reactions. I strongly believe that in order to make changes to what already exists in the design world we have to find the courage to risk being different. Originality is the key to distinction.’ (from the student group ‘being’ Neville Brody to the group ‘being’ Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, online challenging statement 27.4.03) The live debate which followed the online submissions was a two-hour presentation to lecturers and peers with each group giving a seven minute creative performance. The video of this session shows complex reinterpretations of the philosophical positions of eighteen individual artists / designers / typographers, by students who may not personally agree with those positions. This intense on-campus session not only encouraged students to reflect on their own position but showed a vast range of examples of design work. The development of Graduate Attributes through this blended learning project. I used the UTS statement of Graduate Attributes (2000) as a way to code 60 student questionnaire comments, together with 15,000 words from focus group transcripts. In this UTS model there are three main attributes within the ‘Graduate Capability’: 1. Learning to Learn Attribute; 2. Personal Attribute; 3. Professional Attribute. These each have a number of ‘domains’ outlined in the diagram in figure 3. Figure 3 Diagram from the UTS Statement of Graduate Attributes (University of Technology 2000) The following sample quotes are indicative of the students’ development of identifiable graduate attributes using this UTS model as my grid for analysis. The following quote shows knowledge literacies (Learning to Learn attribute) in that the student has taken the time to appreciate the validity of the points of view expressed, and their context in history (professional attribute, contextual domain). The quote also shows that the student has a responsive attitude to the community of ‘budding designers’ and also the autonomy domain in ‘we have to make up our own minds’. ‘I found it interesting that opposing and yet equally valid points of view have existed throughout typography history. It encourages you to think for yourself, realising that as budding designers we have to make up our own minds regarding these things’.(Quote from Q1, second student survey) The next quote shows an appreciation of the potential of more engaging modes of learning as part of a ‘Learning to Learn’ attribute and an appreciation of the need for deeper engagement. It also indicates a personal attribute of reflection about ones own position in society (citizenship domain) ‘It’s a lot better learning this way than say getting given a 1500 word essay to write. Yes, This way you actually have to know more about the typographer. What he or she was like and what they believe in. As I said before, you can reflect upon that and see where you stand as a designer as well.’(Quote from Focus Group 2. transcript 22.5.03) There were many examples from the complete range of Graduate Attributes identified in student responses indicating that a well designed project can be the vehicle for multiple learning objectives. Group work Assessment using SPARK (Self and Peer Assessment Resource Kit). The research case study yielded a rich source of data about the way in which the groups of students responded to rating themselves and their peers online against the range of criteria outlined earlier in this paper. One of the concerns I had about using such a system was whether students would use it responsibly with genuine reflection on their own and their peers performance in the group task. In attempting to determine whether this had been the case, I analysed the frequency of the negative ratings used (i.e. -1: the group member had been detrimental to the group performance in a particular criteria, 0: no contribution, 1: below average contribution). The results of this analysis were very encouraging in that out of almost 3,000 ratings entered only 12 ratings of -1 were used as shown in figure 4 below. Table 2 SPARK ratings entered by students showing responsible use of negative rating scores Total number of ratings entered: 2986 Ratings of -1 (detrimental contribution): 12 ratings entered Ratings of 0 (no contribution): 45 ratings entered Ratings of 1 (below average contribution): 370 ratings entered Ratings of 2 (average contribution): 838 ratings entered Ratings of 3 (above average contribution): 1631 ratings entered Students noted that they appreciated the option to use the -1 rating and their opportunity to influence final assessment marks at the end of the project. ‘Yes, we did it on-line….Yes, I thought it was good because in our group there were some people that slacked off, well, not slacked off, but they just didn’t do as much as everyone else, so doing the ratings, like it felt good…you know, distributing the mark…(Quote from Focus Group 1. 22.5.03)’ This quote shows that the student understands the idea of distributing a group mark and has remembered the term ‘ratings’. The student is also expressing emotional satisfaction ‘like it felt good’ showing that carefully implemented self and peer assessment can have a very positive impact on group-based assessment tasks. Conclusions and reflections In reflecting on the online submissions and the live debate performance I was impressed by the level of engagement and enthusiasm, and quantity and quality of work generated from an online learning task allocated 20% of the total subject assessment marks. There was evidence in the focus group transcripts that the online aspect of this learning design had fuelled student’s enthusiasm by giving them the opportunity of a different online identity through which to express strong opinions.. The live debate performance at the end of the task allowed an active and creative engagement with their own research material. The use of anonymous online group self and peer assessment against specific criteria had the effect of allowing students to relax into their group task when they realised that they would have the opportunity to distribute marks according to the actual contributions of each group member. The fact that a number of students were able to complete the project through minimal online engagement and peer support was an interesting feature of the ‘blended learning’ environment. The self and peer assessment for these students showed that their oncampus contributions were highly valued and acknowledged by the other group members. It was clear from student comments that the clarity of the assessment criteria used and the quality of their integration into the design of the learning task were instrumental in encouraging students to adopt a deep approach to this task. It was also clear that the immediacy of online communication greatly facilitated the flexible engagement of students in the learning task and the assessment processes. There was ample evidence that this online / oncampus approach facilitated deep engagement and the fulfilment of a broad range of learning objectives. The building of dynamic tension through various online activities and engagements between opposing pairs of groups was an important motivational factor. The oncampus live debate presentation was a vital ‘capstone’ of the learning design, giving release to the tension and an opportunity for dramatic engagement, witnessed by peers in a supportive, exciting and richly informative event. It is my conclusion that the best of both online and oncampus worlds was leveraged using a carefully designed blended learning project. Further study is continuing in the formative use of SPARK for group work feedback and the development of the Online Criteria Based Assessment system as an e-portfolio for students. References: Biggs, J. B. (1991). Teaching for Learning: The view from Cognitive Psychology. Victoria, Australia, Hawthorne. Boud, D., R. Cohen, et al., Eds. (2001). Peer Learning in Higher Education. London, Kogan Page. Ramsden, P. (1992). Learning to Teach in Higher Education. London, Routledge. Thompson, D. (2002). Online Learning Environments for Group-based Assessment. ENHANCING CURRICULA: exploring effective curriculum practices in art, design and communication in higher education., London, Centre for Learning and Teaching in Art and Design. University of Technology, S. (2000). Statement of UTS Graduate Attributes, UTS Academic Board. http://www.iml.uts.edu.au/learnteach/design/gradatt.pdf 2003. Whitehead, A. N. (1929). The Aims of Education. New York, The Macmillan Co.