Overview of RAP techniques

advertisement

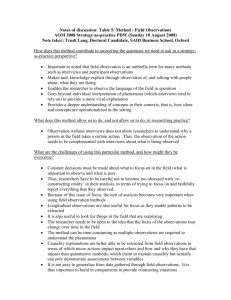

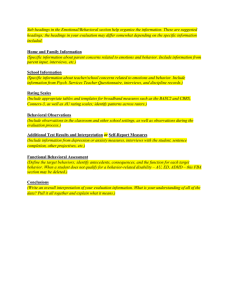

OVERVIEW OF RAP TECHNIQUES OBSERVATION SEMI-STRUCTURED AND STRUCTURED OBSERVATIONS PURPOSE Direct observation is always relevant. On-site visual inspection may provide rapid data on the dynamics within a population group, and of the health, nutrition , shelter, water, sanitation and environmental conditions, among other things. It is used throughout a field visit, including on arrival and departure by air or road. LINKAGES/COMPARISONS TO OTHER METHODS Observation is naturally combined with other methods (e.g. what is seen could be used to cross-check answers from interviews, finding from secondary sources) It will naturally complement techniques such as transect walk/mapping. TECHNIQUES Guidelines for observation are necessary to ensure that data collectors are consistent in terms of what is to be observed, and clear as to why. If different people observe the same things, it is important to standardise observation techniques. In practice it will be useful to test checklists through a preparation exercise in which all participants jointly observe a site and later compare their notes. Observations can be: Semi-structured, the same items are observed in all sites, or Structured, involving counting or verifying an event at a pre-defined interval or location. An example of structured observation is to count every 30 minutes, during a whole day, the number, age and gender of people queuing at a particular water source or food distribution centre. (See core content sheet "The observation plan".) CONSIDERATIONS IN CRISIS AND UNSTABLE CONTEXTS As visual images are often powerful and observations are often perceived as “true”, they must be weighed carefully for bias, based on location (centre/periphery, health centre vs. open community), gender, culture, etc. Look for what is hidden. For example, sickly and malnourished children may be kept out of sight and may be missed unless the researchers specifically ask about them. Both structured and semi-structured observations should involve close co-ordination among researchers or assessment team members to ensure consistency on what is being observed and to cross-check interpretations and explanations. Sketches, videos, photos can help record a wealth of data, but, especially in the context of complex emergencies, they might not be feasible. Overview of RAP techniques- Page 1/7 INTERVIEWS AND DISCUSSIONS INDIVIDUAL INTERVIEWS PURPOSE Individual interviews can be used to gather information from a range of informants: local authorities, local humanitarian actors, the affected populations. They can be done on a cross-section of the population to gather and compare their view (see section on sampling), or to selected key informants to collect insights from individuals with particular expertise on the subject. LINKAGES/COMPARISONS TO OTHER METHODS Compared with other interview and discussion techniques, individual interviews are more likely to provide personal answers and therefore could be better at revealing conflicts than group interviews. Interviews should be always used with observation. Examining the context while doing the interview can help identify contrasting perspectives or the need for more in-depth questioning. Interviews with key informants will focus more on realities affecting the broader community. They may use techniques to draw out such information, for example, depending on type of expertise, timelines, seasonal calendar. TECHNIQUES Semi-structured interviews use a checklist of items to be discussed, for example: Water availability and access: Sources accessible (security, distance, ownership) Quantity available by family (seasonal variations, other variations in availability, line-ups) Factors affecting access for different groups (labour available and how this conflicts with other concerns, distance, transportation and security) CONSIDERATIONS IN CRISIS AND UNSTABLE CONTEXTS Fear, mistrust, trauma and panic. People could say nothing, play things down, exaggerate or lie. Interviews are bound to have a difficult dynamic when they are carried out within a circle of armed guards; or when people are devastated by a disaster. Pressure for having immediate relief is constant in a crisis setting. (see: Slim) Learning to listen and to understand behind words in this context is fundamental. GROUP INTERVIEWS PURPOSE Small discussions with 6 – 12 people who share common characteristics are more likely to discuss sensitive issues because of their common experience. They can convey a large amount of information in a relatively short time. LINKAGES/COMPARISONS TO OTHER METHODS Group interviews can encourage discussion on sensitive issues that individual interviews could not convey; similar backgrounds will make participants relatively more relaxed and they will often express feelings and beliefs or recount practices that they would not convey otherwise. Overview of RAP techniques- Page 2/7 TECHNIQUES A facilitator will raise pre-defined issues and ask the group to discuss them. Some tips: Be flexible and allow new and unexpected issues to be brought up and discussed Prevent a few individuals from dominating the discussions, have respect for every participant’s right to speak Even in an emergency context, a comfortable environment with no interruptions (e.g. a closed area) is needed Establish equality and trust between yourself and participants Record the discussion and agree on the method of doing so, e.g. blackboard, flip chart (taping could be intrusive) CONSIDERATIONS IN CRISIS AND UNSTABLE CONTEXTS Group interviews are useful to discuss questions on which there is consensus but that would not be comfortably expressed in individual interviews (e.g. misuse of funds or resources). The solidarity of the groups can help express otherwise sensitive issues They can be used to involve groups that often "do not have a voice", e.g. women and children. They are likely to be shy with external visitors, but more talkative in groups They are more likely to generate consensual issues: the self-correcting mechanism of the groups means that impressions not shared by the group are immediately corrected INFORMAL SURVEYS PURPOSE Examples of informal surveys include: collecting information on family structure among the displaced (presence of adult men, teenage caregivers with children) at a central meeting point or water distribution point; verifying water quantity by going to a few water sources, measuring the amount of water carried by a number of people and asking them how many such trips they will take each day. (This could be useful if conflicting information has been provided.) LINKAGES/COMPARISONS TO OTHER METHODS A very rough source of information that serves to cross-check what is provided in key informant or focus group interviews Using well-chosen key informants with cross-checking can often provide better information more quickly TECHNIQUES Typically, 25 – 50 interviews will be done using purposive sampling and convenience sampling and a semistructured questionnaire, leaving interviewers free to ask additional questions whenever relevant. (A common use of informal surveys in emergencies is to provide a rapid check on nutrition status using the middle upper arm circumference (MUAC) measure. This is not advised because of the enormous potential for error — both due to the lack of sampling structure and actual errors in measurement.) CONSIDERATIONS IN CRISIS AND UNSTABLE CONTEXTS Useful when information needs are limited to detection of a problem or determining a very rough order of magnitude, such as presence of unaccompanied children, for which follow-up assessment work will be necessary. This is particularly true for very rapid surveys of an area during the acute phase of a crisis. Informal surveys must not be considered as a substitute for formal surveys with appropriate statistical sampling; as quantitative data, it remains extremely limited. Informal survey results must be interpreted and used with great care, especially true for external relations where careful comment on methodological limitations might not be absorbed and repeated correctly. Overview of RAP techniques- Page 3/7 RANKING AND SCORING RANKING AND SCORING PURPOSE Ranking and scoring methods are used to identify priorities or preferences, as well as the criteria used by the respondent in order to place them. Wealth ranking is used to investigate perceptions of wealth differences in a community (e.g. the poorest, the middle, the richest). Ranking implies select priorities (the best, the second best…), while in scoring exercises, participants are asked to give a score (e.g. marks out of 100) to different options. In practice, the two methods can be combined (as shown in the examples in the "techniques" section below. LINKAGES/COMPARISONS TO OTHER METHODS Ranking and scoring are useful tools during interviews, group meetings, etc. Conversely, they can be used on their own, perhaps leading to more direct questions ("Why is problem x more serious than problem y?") TECHNIQUES PRIORITY RANKING: 1. Identify an issue (e.g. problems of water collection) 2. List possible reasons/alternatives, perhaps pointed out by people in a short preliminary discussion (e.g., reasons: distance, queuing time, security at taps) 3. Ask participants to rank the problems: What is the biggest problem when collecting water? The second biggest? The third? The smallest? 4. Analyse results Comparing total scores identifies the most important problem of the group as a whole (in this case: small containers) The analysis of the table can help identify particular concerns for some individuals: e.g. why security is an important issue for A and E? Example: Respondents priority ranking of problems in water collection Problem Distance to source Queuing time Small containers Lack of storage Steep hill Security at taps Respondents’ ranking (6=most important, 1=least important) A B C D 4 3 2 5 3 4 3 2 5 6 5 6 2 5 6 4 1 2 4 1 6 1 1 3 E 2 3 4 6 1 5 Total score 16 15 26 23 9 16 MATRIX RANKING Allows analysis of a range of options according to objective criteria: Comparisons: e.g. different food security constraints (seeds, tools, labour, rains, pests, security) can be ranked according to whether they were more or less problematic before or after a crisis situation Choices among different options according to a range of pre-established criteria (e.g. choosing a site for a health centre). Overview of RAP techniques- Page 4/7 The ranking is done along two axes: one displaying the options (e.g. in the example of site selection, the different sites) and one with the different criteria (e.g. proximity to school, central location, good road access, space available, state of repair of building). A common scale is then used to rate each site and each criterion (e.g. from very good to very bad). In analysing the results, criteria can be weighted according to their relative importance. Example: matrix ranking of potential sites for health centre 'X' Criteria Central location Proximity to school Road access […] Site A Very good Good Very bad Site B Good Good Bad Site C Bad Good Very good Numeric ratings can be used. Matrix ranking can also be combined with proportional piling where participants are less comfortable with numeric ranking or have difficulty with structured scales. For more refined analysis, the criteria could be weighted (e.g. before summing them up, their relative importance could be acknowledged by multiplying them for a weighting factor). PROPORTIONAL PILING This is a visual form of estimating proportions. One hundred beans, sticks, or the locally current form of counters is used. Interviewees can be asked, for example, to show the distribution between women with husbands (married or not) and women without, making piles from the 100 counters, which represent each group. An initial answer can be used for further probing, breaking down distributions. This is most useful for getting some sense of the population profile where no background survey exists or can be conducted, as well as for understanding relative importance of food sources, disease prevalence, etc. Mothers with husbands present Mothers with husbands away Mothers with no husbands CONSIDERATIONS IN CRISIS AND UNSTABLE CONTEXTS In their most basic form, ranking and scoring techniques can take a few minutes with a small group of people. Though they require repetition to draw conclusions, they can help get at least very rough orders of magnitude and understand preferences. Overview of RAP techniques- Page 5/7 DIAGRAMMES COMMUNITY MAPS PURPOSE Community maps, drawn in groups, are useful to learn about an area, and about how different groups use it. LINKAGES/COMPARISONS TO OTHER METHODS Community maps can be used During interviews, group meetings, etc. To cross-check maps that might be rapidly outdated by the development of a crisis With direct observation CONSIDERATIONS IN CRISIS AND UNSTABLE CONTEXTS Community maps can be useful tools for assessing different perceptions of the same reality. For example, community maps drawn by women may be quite different from those drawn by men Mapping can be a good orientation activity at the beginning of an assessment, particularly to establish a spatial understanding of patterns, such as population movements, trade routes, resource distribution and population sub-groups, and to begin to identify key issues in livelihood strategies TRANSECT WALK PURPOSE A transect walk is a simple observation technique. The researcher/assessment team member walks from one extreme of the community to the other with a local community member as a guide to answer questions along the way about what is observed. Information can be recorded in a transect diagram (a cross-section view of the community) and/or can be transferred onto a geographical map. LINKAGES/COMPARISONS TO OTHER METHODS This can be combined with a checklist for semi-structured observation, or it can be used for unstructured observation and probing. It adds to observation methods, by structuring a focus on differences according to physical context, i.e. difference between the centre and the periphery of the community, different eco-zones and livelihood patterns, different accessibility to key services or activities. CONSIDERATIONS IN CRISIS AND UNSTABLE CONTEXTS Transect walk is a very useful tool in acute phases of crisis, for example during rapid assessment visits. Security can limit the mobility of researcher in particularly unsafe areas, and this technique may be not applicable. Be aware of the presence of minefields. Overview of RAP techniques- Page 6/7 TIME LINES PURPOSE Event xxx Crisis outset Event yyy Time lines are flow charts showing the sequence of different events. They can be used to study people’s daily activity, or examine the life cycle of a programme. LINKAGES/COMPARISONS TO OTHER METHODS Timelines can be used during interviews, group meetings, etc. CONSIDERATIONS IN CRISIS AND UNSTABLE CONTEXTS It is useful to identify key events locally, which will involve identifying how and when the crisis has affected the local area. SEASONAL CALENDARS PURPOSE A seasonal calendar is usually drawn on the ground in the form of a chart, placing months or seasons (using locally appropriate terms) along the top or bottom of the chart and tracing the trends of interest through the year. LINKAGES/COMPARISONS TO OTHER METHODS Seasonal calendars can be used during interviews, group meetings, etc. Ranking can be used to help build a seasonal calendar, e.g. "in what month do you have the most work to do?" followed by questions about the type of work CONSIDERATIONS IN CRISIS AND UNSTABLE CONTEXTS This can be used to understand annual patterns (normal and otherwise) regarding the environment, population movements, labour, agricultural production (hunger gaps), disease trends, access to health services, market prices, availability of disposable income, etc. It helps to identify key issues in livelihood strategies. This need not be repeated many times. Overview of RAP techniques- Page 7/7