Oral Cancer

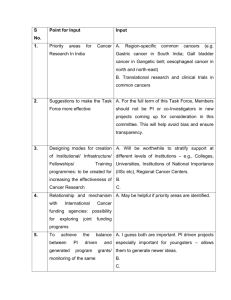

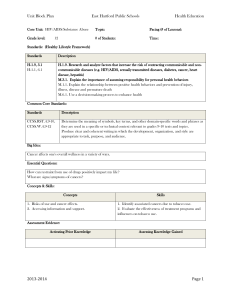

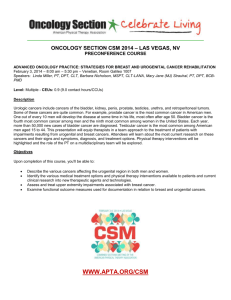

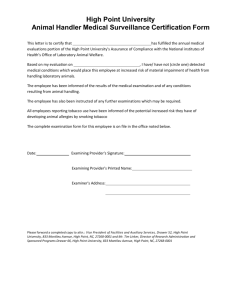

advertisement