new mexico archeological council 2006 fall conference

advertisement

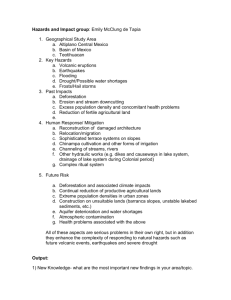

NEW MEXICO ARCHEOLOGICAL COUNCIL 2010 FALL CONFERENCE Indigenous Mobile Groups (and Other Light Signatures) of the Protohistoric and Historic Periods Highly mobile indigenous groups were present in and raided and traded into New Mexico during the terminal prehistoric and early Spanish periods. These include various Apache (Jicarilla, Mescalero, Chiricahua), Ute, Jano, Jocome, Manso, and Suma groups, as well as others. Settlements and material culture associated with these groups left slight traces on the landscape that have often been overlooked or incorrectly categorized. Shrines will also be discussed, as will new evidence relating to the UteNavajo debate. Efforts over the past decade have honed in on these lighter signatures. Sites of this period, of mobile groups, and of specialized activities (such as ritual and game traps) can now be routinely recognized. Learn their archaeological signatures. Hibben Center, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque Saturday, November 13, 2010 Co-sponsored by the Maxwell Museum of Anthropology, UNM ►►►Subject to change before or during the conference.◄◄◄ Saturday, November 13: All Day 9:00–4:00 Standing exhibits and posters (Hibben Atrium) Saturday, November 13: Morning Session (Southern & Eastern Groups) 8:00–8:45 On-site registration; continental breakfast (Hibben Atrium) 8:00–8:45 NMAC Business Meeting (Hibben 105) Papers are 15 minutes Saturday, November 13: Morning Session (Southern & Eastern Groups) 8:00-8:45 On-site registration; continental breakfast (Hibben Atrium) 8:00-8:45 NMAC Business Meeting (Hibben 105) 8:45-9:00 INTRODUCTION Rethinking Mobility: Method and Theory for the 21st Century NMAC Fall Conference, Nov. 13, 2010, Page 2 _____________________________________________________________________________ (Deni J. Seymour) 9:00-9:15 Excavations in the Carrizalillo Hills Region of Southwestern New Mexico Reveal Protohistoric Mobile Group Camps (Alex Kurota and Leslie Cohen, Office of Contract Archeology, University of New Mexico) 9:15-9:30 Large Rocks, Small Rocks, Rocks in a Ring: Three Types of Protohistoric Thermal Features in Southwestern New Mexico (Joanne Gilby, Office of Contract Archeology, University of New Mexico) 9:30-9:45 Protohistoric Sites in the Cedar Mountains, New Mexico (Meade F. Kemrer) 9:45-10:00 A Fateful Day in 1698..."A Glorous Victory": Defining the Jano, Jocome, Manso, Suma, and Apache in the Battle remains at Santa Cruz de Gaybaniptea (Deni Seymour) 10:00-10:15 Discussion 10:15-10:30 Break; continuation of continental breakfast. 10:30-10:45 Session Statement 10:45-11:00 Plains Apache Diaspora: Implications for Archaeo-ethnicity (Jeffery R. Hanson, Statistical Research) 11:00-11:15 Identification of Apache Iconography at Southern New Mexico and West Texas Rock Art Sites (LeRoy Unglaub) 11:15-11:30 The Hormiguero Site: A Large Peloncillo Mountain Site as a Guide for Identifying Apachean Material Culture (Deni J. Seymour) 11:30-11:45 Athapaskan Migration and Jicarilla Ethnogenesis in Eastern Colorado during the 15th and 16th Centuries (Kevin Gilmore and Sean Larmore, ERO Resources Corporation) 11:45-12:00 Discussion 12:00-1:30 Break for lunch. A Pueblo oven bread demonstration and sale of Indian tacos, posole, fry bread, oven bread, etc. will take place in the Maxwell Museum courtyard to coincide with the conference. Saturday, November 13: Afternoon Session (Northern Groups and the Ute-Navajo Controversy) Saturday, November 13: Afternoon Session (Northern Groups and the Ute-Navajo Controversy) 1:30-1:35 Session Statement NMAC Fall Conference, Nov. 13, 2010, Page 3 _____________________________________________________________________________ 1:35-1:50 Shrines and the Sacred Landscape (Dave Lugare, BLM) 1:50-2:05 Needzii': Diné Game Traps on the Colorado Plateau (Jim Copeland, Bureau of Land Management) 2:05-2:20 Emerging from the Shadows: In Quest of the Yavapai of the Verde Valley (Peter J. Pilles, Jr., Forest Archaeologist, Coconino National Forest) 2:20-2:35 Squeezing Blood from Stone Flaking Debris: Using Debitage as a Cultural and Chronological Marker (Matthew Bandy, SWCA Environmental Consultants) 2:35-2:40 Questions and Introductory Comment-The Ute and Navajo Controversy (Dave Brugge) 2:40-3:00 The Old Wood Calibration Project and Colorado's Missing Record of Ute Prehistory (Steven G. Baker, Centuries Research; Jeffrey S. Dean and Ronald H. Towner, Laboratory of Tree Ring Research) 3:00-3:15 The Colorado Wickiup Project (Curtis Martin, Dominquez Archaeological Research Group) 3:15-3:30 Site 42UN5406: A Numic and Ancestral Pueblo Ceramic Assemblage in the Uintah Basin, Uintah County, Utah (James A. Truesdale, David V. Hill, and Christopher James ("CJ") Truesdale) 3:30-3:40 Break; with snack 3:40-3:55 The Archaeological Difference between Ute and Navajo (David Brugge) 3:55-4:30 Discussion, Additional questions and comments NOTE: certificates of attendance for the Saturday symposium will be handed out at the end of the day, not before. Partial attendance does not count. NMAC Fall Conference, Nov. 13, 2010, Page 4 _____________________________________________________________________________ Posters: Ute-Comanche Rock Art in the Northern Rio Grande (Pilar, NM) Annie Danis and Severin Fowles of Barnard College, Columbia University This poster presents a large, recently documented site of Plains tradition rock art in the Orilla Verde recreational area (BLM) near Pilar, NM. The rock art depicts dynamic scenes of battle and raiding as well as iconic plains imagery such as tipis and parfleches, unprecedented in the research of the area. The site is a dramatic addition to the narrative of Plains presence in the Northern Rio Grand in the early historic period, and offers a visually striking account of Comanche-Ute (and possibly Apache) movement through the Taos area. The Border Fence Project: Summary of Archeological Research in Southwestern New Mexico Leslie Cohen and Alexander Kurota Office of Contract Archeology, University of New Mexico Between February 2008 and January 2009, the Office of Contract Archeology conducted extensive surveys and limited excavations along the New Mexico-Mexico border as a series of contracts to enable the construction of the international border fence. The project became to be known as the Border Fence Project. The work was divided into four major research areas: (1) Eastern Boot Heel, (2) Three Sites, (3) Nineteen Canyon, and (4) the Santa Teresa Area. The research has brought to light new information about the subsistence practices of Archaic huntergatherers, late Formative period farmers, and protohistoric nomadic people. Survey, excavation, archival research, and interviews with local residents highlighted the complex nature of life along the New Mexico-Mexico border during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Native American Lithic Procurement Patterns and Sites in the Boot Heel of Southwestern New Mexico Kate Zeigler (1), Chris Hughes (2), Alex Kurota (2), and Patrick Hogan (2) 1 Zeigler Geologic Consulting, Albuquerque 2 Office of Contract Archeology, University Of New Mexico Multidisciplinary field projects can be very useful to a more fundamental understanding of the world around us. The combination of archeology and geology enhances our understanding of human behavior and human use of the landscape with an intimate knowledge of geologic processes and available lithic materials. OCA's excavations and surveys along the international border fence reveal patters of use of geologic materials during the Archaic, Formative, and Protohistoric Native American groups. Thousands of lithic artifacts and groundstone were documented from the southern Peloncillo mountains to the Carrizalillo Hills west of Columbus. The majority of rock types utilized by native people are local siliceous volcanic materials. NMAC Fall Conference, Nov. 13, 2010, Page 5 _____________________________________________________________________________ However, artifacts made from obsidian were transported into the region from northern Mexico and eastern Arizona indicating long-distance travel and/or trade routes. ABSTRACTS In alphabetical order, by presenter or senior presenter Steven G. Baker (Centuries Research); Jeffrey S. Dean and Ronald H. Towner (Laboratory of Tree Ring Research, University of Arizona) The Old Wood Calibration Project and Colorado’s Missing Record of Ute Prehistory “The Old Wood Calibration Project” (OWCP) has been a collaborative effort between Centuries Research, Inc. and the Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research at the University of Arizona. The project was initiated in 2004 and has been investigating a suspected “old wood effect” in the radiocarbon and tree ring dating of hearth fuel woods from archaeological sites in western Colorado. The OWCP has demonstrated that 1000+ year-old pieces of dead wood suitable for burning are present on the current landscape and that elements more than 600 years old are relatively abundant. It has also empirically demonstrated that the probability is high (virtually 100 percent) that radiocarbon or tree ring dates from pinion or juniper charcoal from hearths or other thermal features will be significantly older than the human acts of building and maintaining a fire with such pieces of dead wood. These ages will commonly be significantly earlier than the ranges indicated by even the two sigma confidence levels in radiocarbon dating. Such confidence levels alone should thus no longer be relied upon for approximating the dates of occupations. In the project’s three study areas of Colorado’s western slope three different minimal mean-age correction factors were determined. These range from 482 years on the Douglas Creek Arch to 219 years further south in the Montrose area. Regional radiocarbon dates based on hearth fuel woods can accordingly no longer be accepted at standard confidence levels but must be adjusted by adding correction factors. The OWCP suggests that the dating chronologies currently in use relative to the occupations by Colorado’s Ute Peoples significantly overstate their age. Even when minimal correction factors are applied to the radiocarbon dates for bona fide Ute sites, the archaeological record for the Ute presence in western Colorado moves forward in time to the very late prehistoric or early historic contexts at least. Ute sites from this time frame are both obvious and not uncommon in western Colorado. This interpretation relating to the late time frame for the Ute occupation is supported by both linguistic and rock art data as well as negative data stemming from a currently perceived near total absence of Ute sites at demonstrable prehistoric time depth. These findings appear to explain why, despite our gains in learning to identify the Ute archaeological culture, evidence of such an older Ute occupation has to date proven to be so elusive. Beyond Colorado the OWCP has major implications for the prehistoric chronometric record of the Desert West. Work is now underway to further test these findings and to carry the research into additional areas. Matthew Bandy (SWCA Environmental Consultants) NMAC Fall Conference, Nov. 13, 2010, Page 6 _____________________________________________________________________________ Squeezing Blood from Stone Flaking Debris: Using Debitage as a Cultural and Chronological Marker The flake scatter is one of the most common types of archaeological site routinely encountered in archaeological inventories. However, the information potential of these sites is severely limited by our inability to place them within a chronological context. Without an idea of when they might date to, it is difficult to assess changes in human behavior on a landscape scale. The problem is particularly acute for mobile populations that typically deposit few chronologically diagnostic artifacts. This paper presents an approach for using lithic debitage as a chronological indicator. The approach is illustrated with an example from northwestern Colorado. Jim Copeland (Bureau of Land Management) Needzii': Diné Game Traps on the Colorado Plateau Game traps recorded by Navajo Lands Claim archaeologists across the Colorado Plateau and more recently by the BLM in the San Juan Basin offers some insight to the level of cooperation and effort required to conduct drive hunts. Understanding the location and placement of these features may help in the interpretation of other sites on the landscape. The results of some field surveys associated with game traps are also presented. Joanne Gilby (Office of Contract Archeology, University of New Mexico) Large Rocks, Small Rocks, Rocks in a Ring: Three Types of Protohistoric Thermal Features in Southwestern New Mexico During OCA’s Border Fence Project excavations, groups of thermal features in the Carrizalillo Hills region provided twelve surprising radio-carbon assays, all dating to the Protohistoric/Early Historic era. These sites are therefore interpreted as being of Apache or other protohistoric group affinity. Analysis of the morphology and the macrobotanical/faunal remains from numerous thermal features aided in deciphering their discrete physical attributes, assessing their function, and ultimately placing them into emerging typological categories. Three distinctive thermal feature types are presented here to offer a beginning typology of protohistoric thermal features for southwestern New Mexico. This typology leads to the conclusion that each type is a specialized construction, differently using rocks and other attributes for temperature and heat duration control. Kevin Gilmore and Sean Larmore, ERO Resources Corporation Athapaskan Migration and Jicarilla Ethnogenesis in Eastern Colorado during the 15th and 16th Centuries NMAC Fall Conference, Nov. 13, 2010, Page 7 _____________________________________________________________________________ Like all migrations, the movement of Athapaskans from their northern homeland into the area they occupied at the time of contact was the end result of a combination of social and environmental factors. Human migrations are rarely the product of unilinear movement of population; they are instead the product of a complex sequence of stages usually involving back and forth movement of both people and information. Sites attributed to the Proto-Apache in Colorado dated to the 15th and 16th centuries provide evidence for both chain and reverse migration strategies used by Athapaskans to move through both plains and mountain landscapes. Although the evidence is thus far sparse, material culture from these sites, including the remains of a habitation structure from the Eureka Ridge site in the mountains of central Colorado, suggest that by the 15th and 16th centuries (if not earlier) the Athapaskans living in Colorado were already in possession of the adaptations and material culture similar to that identified with both the Dismal River culture and the Jicarilla of the historic period. This material culture includes micaceous ceramic wares, tri-notched projectile points, snub-nosed endscrapers, double-bitted drills with lateral lugs, and use of lithic raw material from the Jemez Mountains. Jeffery R. Hanson (Statistical Research, Inc.) Plains Apache Diaspora: Implications for Archaeo-ethnicity Four of the more significant challenges of assigning tribal identification to archaeological sites and complexes are migration, mobility, ethnogenesis, and cultural change. Each of these factors has implications for the nature and content of archaeological assemblages. These challenges are illustrated by the Plains Apache diaspora, in which several groups of Apaches from a common ancestral area experienced significant territorial shifts and cultural changes which in some cases severed their connection to their archaeological past. Meade F. Kemrer Protohistoric Sites in the Cedar Mountains, New Mexico Surveys in the Cedar Mountains identified protohistoric and historic Native American sites. This paper describes the radiocarbon dates, settlement characteristics, and artifacts. These sites conform to with the nomadic occupations Seymour described and found in the southern American Southwest. Alex Kurota and Leslie Cohen (Office of Contract Archeology, University of New Mexico) Excavations in the Carrizalillo Hills Region of Southwestern New Mexico Reveal Protohistoric Mobile Group Camps The Office of Contract Archeology recently excavated four Protohistoric period sites in the Carrizalillo Hills region of southwestern New Mexico. The research conducted under the Border Fence Project revealed new information on these mobile group camps from the southern NMAC Fall Conference, Nov. 13, 2010, Page 8 _____________________________________________________________________________ Southwest. Twelve radiocarbon and two thermoluminescence dates place the four sites and all excavated features consistently into the mid-15th to the late 19th century. This research uncovers new evidence for these mobile groups’ subsistence practices, lithic procurement, lithic tool manufacture and recycling, seasonality of use, and their movement throughout the landscape. Curtis Martin (Dominquez Archaeological Research Group) The Colorado Wickiup Project The ongoing Colorado Wickiup Project has documented 366 aboriginal wooden features (wickiups, tree platforms, etc.) on 58 sites in western Colorado. The findings have provided new understanding regarding the Protohistoric and Early Historic Northern Ute and their continued occupation of traditional, off-reservation, homelands after their removal to reservations. Dendrochronological dates from metal ax-cut feature elements range from A.D. 1815 to 1915/1916, with over half of the dates indicating occupation during post-“removal” times (after 1881). Two of the sites were occupied after 1900. Two resources have revealed relatively unique site types in the archaeological record of western Colorado. At one, the Ute Hunters’ Camp (5RB563), canvas wall tents provided shelter for the occupants occupied with meat and hide processing, bullet reloading, and, possibly, leather working. Another, the Black Canyon Ramada (5DT222), includes the partially collapsed remains of a Protohistoric flat-roofed sunshade. Based on our findings, this author proposes that Phase V of Baker’s Model of Ute Culture History be divided into two sub-phases. The proposed Phase V-A, or “Ungacochoop Phase,” would embody post-1900 Early Historic Era sites. Peter J. Pilles, Jr. (Coconino National Forest) Emerging from the Shadows: In Quest of the Yavapai of the Verde Valley The Pai people have occupied central Arizona for centuries, yet their archaeological presence has seldom been recognized. As mobile hunter/gatherers, their material culture was mostly of lightweight, perishable materials, leaving little but remnants of flaked and ground stone tools to indicate their camps. Consequently, Yavapai sites have commonly been overlooked, masked by later occupants or thought to be Archaic period sites. This paper summarizes artifactual, architectural, technological, and pictorial data that is thought to indicate Yavapai use and occupation of the Verde Valley. Different theories about the origins of the Yavapai are discussed in light of oral traditions and archaeological evidence that date the appearance and continuity of the Pai people in the archaeological record. Finally, it is suggested that relations between the Yavapai and earlier occupants of the Verde Valley may not have been as bellicose as some have theorized. History and ethnology provide other examples of hunter/gatherer and agriculturalist interactions that should be examined as alternatives to existing concepts. Deni J. Seymour (The Southwest Center) INTRODUCTION Rethinking Mobility: Method and Theory for the 21st Century NMAC Fall Conference, Nov. 13, 2010, Page 9 _____________________________________________________________________________ Existing conceptions that distinguish limited-activity sites and residential sites are detrimental for understanding material and spatial evidence related to mobile groups. Similarly, the Binforddevised models of site structure which are based on ethnoarchaeologically derived information are inappropriate for Southwestern open sites occupied for the short term. Despite the prevalence of these models, archeological evidence indicates that sites are much more dispersed, without a residential-core focus and that activities are not focused on hearths. Worldwide evidence of this pattern provides a cross-cultural basis for assessing its significance for site interpretation and boundary definition. Deni J. Seymour The Hormiguero Site: A Large Peloncillo Mountain Site as a Guide for Identifying Apachean Material Culture. A sizable ancestral Apache site in the Peloncillo Mountains has distinctive structure outlines, storage platforms, rock art, pottery, and other features and artifacts. The nature of this site provides information on how to identify Apache sites, how to distinguish between Apache and non-Apache mobile groups, and how to distinguish between various Apachean groups. It also provides a way to connect ethnographic sources to the archaeological record to understand landscape use, terrain selection, and the Apachean perception of their neighbors. James A. Truesdale, David V. Hill, and Christopher James (“CJ”) Truesdale Site 42UN5406: A Numic and Ancestral Pueblo Ceramic Assemblage in the Uintah Basin, Uintah County, Utah The dating of the arrival of Numic-speaking peoples into the Southwest is currently controversial. Clear associations of material culture that can be associated with Numic occupations dating prior to the eighteenth century are rare. The ceramic and lithic assemblage from 43UN5406 indicates the presence of Numic-speakers in northeastern Utah and the Greater Southwest by the early fourteenth century. Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL) dating for a finger-nail impressed sherd supports the fourteenth century occupation of the site. LeRoy Unglaub Identification of Apache Iconography at Southern New Mexico and West Texas Rock Art Sites Southern New Mexico and West Texas has a number of rock art styles to include multiple archaic styles, the Jornada-Mogollon style which is the principal rock art style in this region, Apache style, and possibly others. Some Apache iconography is relatively easy to identify but NMAC Fall Conference, Nov. 13, 2010, Page 10 _____________________________________________________________________________ becomes more difficult especially at sites with multiple rock art styles. This paper will discuss and illustrate the methods and criteria used to identify Apache iconography at a number of rock art sites in Southern New Mexico and West Texas.