Arts Research Compilation - McKay School of Education

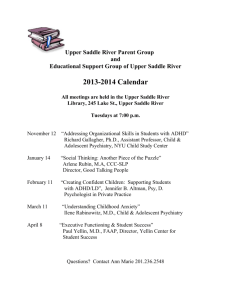

advertisement