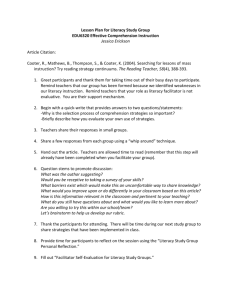

Literacy in Conflict Situations

advertisement