where and who are the world`s illiterates: china

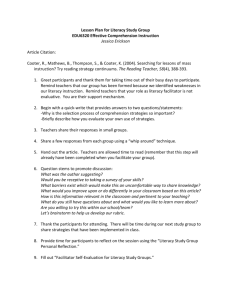

advertisement