Pressure Ulcers - British Geriatrics Society

advertisement

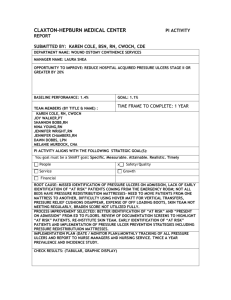

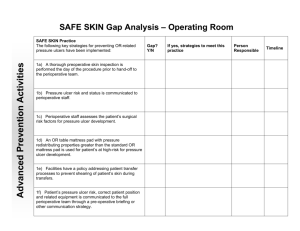

British Geriatrics Society Best Practice Guide Pressure Ulcers 1. Executive Summary Pressure ulcers are an unwanted complication of illness, severe physical disability or increasing frailty. They are caused by pressure and/or shear forces over a bony prominence in the presence of a number of risk factors, the most important of which is immobility. Data on older adults from the UK General Practitioner Research Database identified a pressure ulcer incidence of 1.61%. A number of medical conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; cerebro-vascular accident; diabetes mellitus; hip fracture and hip surgery have been significantly associated with pressure ulcers. Geriatricians thus have an important role to play in the prevention and management of pressure ulcers through and awareness and understanding of current best practice. It has to be accepted that it is not possible to prevent all pressure ulcers, but with appropriate care, the majority can be prevented. Prevention strategies need to address the specific risk factors identified in the initial assessment. The commonest strategies are: Pressure relief by means of repositioning and/or the use of pressure redistributing equipment Consideration of the needs of patient when seated in relation to pressure relief Improvement of nutritional status Skin care including on-going monitoring of skin status and any indications of pressure damage. Many of the strategies used for pressure ulcer treatment are the same as those employed for pressure ulcer prevention, although they may be more intensive than those used in prevention. Assessment of the pressure ulcer should include: Category – shows severity Size Position on the body – may affect dressing selection Level of exudate – will affect dressing selection and frequency of dressing change Pain assessment – many ulcers are painful for the patient Healing may not be a fast process, but generally as long as the patient has adequate pressure redistribution, good nutrition and appropriate wound management, the ulcer will heal in most instances. Geriatricians will encounter individuals at risk of pressure ulceration as well as those with established pressure ulceration on a regular basis. As part of Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment and MDT working they are best placed to manage such individuals appropriately. Additionally, familiarity with risk stratification scales and relevant, often local, guidelines and policies will prove invaluable adjuncts to optimal management. 2. Introduction Pressure ulcers are an unwanted complication of illness, severe physical disability or increasing frailty. They are caused by pressure and/or shear forces over a bony prominence. There are a number of risk factors associated with pressure ulceration, the most important of which is immobility. Additional risk factors include poor nutritional status, loss of sensation, poor perfusion and alterations to intact skin, possibly due to a previous history of pressure ulcers. Furthermore a number of medical conditions were found to be significantly associated 1 with pressure ulcer development including: Alzheimer’s disease; congestive heart failure; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; stroke; diabetes mellitus; deep venous thrombosis; hip fracture; hip surgery; limb paralysis; lower limb oedema; malignancy; Parkinson’s disease; rheumatoid arthritis; and urinary tract infections. Pressure ulcers have their highest prevalence amongst frailty, and Geriatricians thus have an important role to play in the prevention and management of pressure ulcers through and awareness and understanding of current best practice. There are no published national audits of the prevalence of pressure ulcers in the UK. In the last decade, surveys in other countries found a prevalence in the range of 10-22% of inpatients. The European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel published a pilot survey in 5 European Epidemiological studies in 2005, including over 2500 patients from 15 hospitals in the UK, and found a UK prevalence of 23%, or 13.9% if only including Category 2 or above ulcers (Vanderwee). Data on older adults from the UK General Practitioner Research Database identified a pressure ulcer incidence of 1.61%. In spite of this huge prevalence and the lack of national audit data, the National Outcomes Framework for 2012/13 has defined 4 avoidable harms, namely category 2-4 pressure ulcers, medication errors, VTE and Healthcare associated infections within the NHS Safety Thermometer CQUIN. This will provide new incentives to reduce pressure ulcer incidence. 3. Definitions / Terminology The following definition is the most recent and developed for international guidelines by the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel and European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP/EPUAP, 2009) in a joint collaboration. A pressure ulcer is localised injury to the skin and/or underlying tissue usually over a bony prominence, as a result of pressure, or pressure in combination with shear. A number of contributing or confounding factors are also associated with pressure ulcers; the significance of these factors is yet to be elucidated. This pressure ulcer classification is used widely across the UK. The term category, rather than grade or stage, is now preferred. Category I: Non-blanchable erythema Intact skin with non-blanchable redness of a localized area usually over a bony prominence. Category II: Partial thickness skin loss Partial thickness loss of dermis presenting as a shallow open ulcer with a red pink wound bed, without slough. May also present as an intact or open/ruptured serum-filled or serosanginous filled blister. Category III: Full thickness skin loss Full thickness tissue loss. Subcutaneous fat may be visible but bone, tendon or muscle is not exposed. Slough may be present but does not obscure the depth of tissue loss. Category IV: Full thickness tissue loss Full thickness tissue loss with exposed bone, tendon or muscle. Slough or eschar may be present. The additional category of unstageable is also recommended by the Tissue Viability Society for reporting systems within England (TVS, 2012). Unstageable/ Unclassified: Full thickness skin or tissue loss – depth unknown Full thickness tissue loss in which actual depth of the ulcer is completely obscured by slough (yellow, tan, grey, green or brown) and/or eschar (tan, brown or black) in the wound bed. 2 4. Health Policy and Guidance There are numerous policy documents and guidelines in relation to pressure ulcers. Quality Improvement Productivity and Prevention (QIPP) in England: http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Healthcare/Qualityandproductivity/QIPPworkstreams/DH_11 5447 Health Improvement Scotland Best Practice Statement: http://www.healthcareimprovementscotland.org/previous_resources/best_practice_st atement/prevention_and_management_of_p.aspx Skin Bundle in Wales: http://www.1000livesplus.wales.nhs.uk/opendoc/179648 NICE Pressure Ulcer Guidelines: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/index.jsp?action=byID&o=10972 Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Ulcers: http://www.epuap.org/guidelines/ National Patient Safety Agency: http://www.npsa.nhs.uk/corporate/news/nhs-toadopt-zero-tolerance-approach-to-pressure-ulcers/?locale=en NHS Commissioning for Quality and Innovation Payment Framework (CQUIN): http://www.institute.nhs.uk/commissioning/pct_portal/cquin.html 5. Pressure Ulcer Prevention It has to be accepted that it is not possible to prevent all pressure ulcers, but with appropriate care, the majority can be prevented. At a very simple level, prevention means identifying those at risk and instigating appropriate prevention strategies according to individual need. However, it is not always straightforward to recognise those at risk. A number of risk calculators are available for use, but they all have limitations and so produce false positives (those deemed to be at risk who do not get a pressure ulcer) or false negatives (those whose score says they are not at risk but who develop pressure damage). NPUAP/EPUAP (2009) recommend that risk assessment should include a comprehensive skin assessment and clinical judgement as well as using a risk calculator. Skin assessment is often poorly done, but is most important to identify potential areas of vulnerability. Prevention strategies need to address the specific risk factors identified in the initial assessment. The commonest strategies are: Pressure relief by means of repositioning and/or the use of pressure redistributing equipment Consideration of the needs of patient when seated in relation to pressure relief Improvement of nutritional status Skin care including on-going monitoring of skin status and any indications of pressure damage. Pressure relief is the most important prevention strategy and traditionally was achieved by the use of ‘2 hourly turning’. These days a wide range of pressure redistributing equipment is available and has almost replaced repositioning of patients. This is unfortunate as repositioning is important for more than pressure relief. All hospital beds have a high specification foam mattress as a minimum. If a patient requires a mattress with greater pressure relief then alternating air overlays or mattresses are generally available. These systems have a series of cells which alternately inflate and deflate and have varying levels of sophistication. If a patient is difficult to move or only able to lie in one position then use of a low air loss bed may beneficial. This support system has an integral bed-frame and mattress which is composed of a series of large cells filled with air. The air is slowly ‘lost’ through the cell walls and replaced via the pump resulting in very low pressures in the cells so that the patient lies in rather than on the mattress. 3 It is an important aspect of care for elderly patients to sit out of bed. However, there are a number of aspects to consider in relation to pressure ulcer prevention. It is important that whenever possible patients should be seated in a position that allows them to maintain function as well as reducing pressure and shear. This may require the use of a footstool or foot rest to ensure that feet are not left dangling if they do not reach the floor. Patients should not be left sitting in a chair for long periods of time without pressure relief. Although labour intensive, encouraging patients to lie on the bed for a short rest after lunch is a simple way of ensuring they do not sit for too long at a time. Assessment of nutritional status should be part of the routine care of any patient. A UK survey of 11,278 people in hospitals, care homes and mental health units found 28% of hospital patients and 30% of care home residents to be malnourished (Russell & Elia, 2007). It is well recognised that the elderly are vulnerable to poor nutrition (Guigoz et al, 2002; Cereceda et al, 2004). The International Pressure Ulcer Guidelines recommend that any patient who is recognised to be poorly nourished and at risk of pressure ulceration should be referred to a dietician (NPUAP/EPUAP, 2009). They also recommend that patients who are both at nutritional risk and pressure ulcer risk should be offered a minimum of 30-35 kcal per kg body weight per day, with 1.25-1.5g/kg/day protein and 1ml of fluid intake per kcal per day. The use of nutritional supplements between meals may be a useful way of increasing intake. Skin assessment and skin care is often a neglected area of patient care. Yet skin assessment is the only way of identifying signs of tissue damage. It should be an ongoing process as it is the most effective way of determining the effectiveness of the prevention plan. If there are persistent signs of redness over a pressure area, the prevention plan needs intensifying. The resilience of skin in the elderly is often impaired. Any prevention plan should consider the use of emollients if the skin is dry or barrier products if the skin is excessively moist (Bou et al, 2005; Beekman et al, 2009). 6. Pressure Ulcer Treatment Many of the strategies used for pressure ulcer treatment are the same as those employed for pressure ulcer prevention, although they may be more intensive than those used in prevention. For example, a more sophisticated support surface may be required. It may be helpful to identify the factors/events which led to the development of the pressure ulcer so that they can be addressed where possible. It must also be accepted that for some patients, palliative care may be more appropriate than curative treatment. This section focuses mainly on the wound care aspect of pressure ulcer treatment. Assessment of the pressure ulcer should include: Category – shows severity Size Position on the body – may affect dressing selection Level of exudate – will affect dressing selection and frequency of dressing change Pain assessment – many ulcers are painful for the patient Having assessed the ulcer, the treatment objectives and plan of care can be determined. The overall all goals are to achieve a healthy wound bed and promote healing, however, wound debridement and control of exudate may be necessary in the first instance. An appropriate wound management product should be selected meet the wound requirements. Table 1 provides information about the range of products that are widely available. Keeping a record of simple measurements and wound appearance will provide information about the progress of the ulcer. Pain management will ensure the patient is comfortable. Table 1: Wound Management Products in General Use Category Comment Alginates Useful for all wounds with moderate to heavy exudate 4 Cadexomer iodine Use for sloughy or infected wounds with heavy exudate Capillary - action Wicks exudate away from wound surface, only for heavily exuding sloughy wounds Use with care on fragile skin. Best on epithelialising wounds with low exudate Foams have variable levels of absorbency depending on the brand. Best on granulating wounds May be found as a topical or in combination with other products e.g. alginate. For use in infected wounds May be used for most types of wounds with low to moderate exudate. Not suitable for infected wounds Greater absorbent capacity than hydrocolloids. Useful for wounds with moderate to heavy exudate Donate moisture to dry sloughy or necrotic wounds and assist autolytic debridement. Can be used on wounds with low exudate. Not suitable for infected wounds Silver is an antibacterial and is generally found as a composite dressing with other products e.g. alginates, foams, hydrocolloids. Use on infected wounds These dressings are non-adherent and best used on granulating wounds. Some incorporate a pad for greater absorbency Films Foams Honey Hydrocolloids Hydrocolloid - fibrous Hydrogel Silver Soft polymers Healing may not be a fast process, but generally as long as the patient has adequate pressure redistribution, good nutrition and appropriate wound management, the ulcer will heal in most instances. 7. Models of Service Provision In the UK most pressure ulcer services are run by Tissue Viability Nurses (TVNs). They oversee the provision of pressure relieving equipment such as mattresses and beds as well as working with the clinical team to plan care provision for individual patients. 8. Responsibilities / Role of the Geriatrician Individuals between 70 and 75 years of age have double the incidence of pressure ulcers compared with 55 to 69 year-olds. The greatest incidence of pressure ulcers occurs in the 80 to 84 year age group (Perneger et al, 1998). More than two-thirds of the elderly with pressure ulcers are female. Geriatricians will, therefore, encounter individuals at risk of pressure ulceration as well as those with established pressure ulceration on a regular basis. As part of Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment and MDT working they are best placed to manage such individuals appropriately. Additionally, familiarity with risk stratification scales and relevant, often local, guidelines and policies will prove invaluable adjuncts to optimal management. An excellent further summary of the whole topic is available by Grey (2006). 9. Audit (including clinical governance) Audit of pressure ulcers takes the form of prevalence and incidence surveys. They are generally undertaken by the TVNs and may form part of the CQUIN in some regions. Pressure ulcers may also be the subject of root cause analysis and serious untoward incidents reports. The new NHS Safety Thermometer will providing a constant monitoring of the incidence of ulcers, but of course will rely on self-reporting, and the inaccuracies inherent with multiple assessors potentially using slightly different non-standardised criteria. 5 10. Recommendations A Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment will identify relevant patient factors in relation to pressure ulceration which ensure an effective management plan The majority of pressure ulcers can be prevented by the use of appropriate prevention strategies Patients should have a comprehensive skin assessment as well as assessment of their risk profile before determining a prevention plan Patients with established pressure ulcers require intensified prevention strategies and an overall wound assessment including pain assessment. Auditing pressure ulcer incidence is an important method of monitoring the quality of patient care. 11. References Beeckman D, Schoonhoven L, Verhaeghe, Heyneman A, Defloor T (2009) Prevention and treatment of incontinence-associated dermatitis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 65 (6) 11411154 Bou JE, Segovia GT, Verdu SJ, Nolasco BA, Rueda LJ, Perejamo M (2005) The effectiveness of a hyperoxygenated fatty acid compound in preventing pressure ulcers. Journal of Wound Care, 14 (3) 117-121 Cereceda FC, Gonzalez GI, Antolin JFM< Garcia FP, Tarrazo ER, Suarez CB, Alvarez HA, Manso DR (2003) Detection of malnutrition on admission to hospital. Nutricion Hospitalaria, 18 (2) 95-100 Grey, JE, Harding KG, Enoch A. ABC of Wound healing : Pressure Ulcers BMJ 2006;332:472-4 Guigoz Y, Lauque S, Vellas BJ (2002) Identifying the elderly at risk for malnutrition. The Mini Nutritional Assessment. Clinics of Geriatric Medicine Margolis D, Knauss J, Bilker W, Baumgarten M (2003) Medical conditions as risk factors for pressure ulcers in an out-patient setting. Age & Ageing, 32: 259-264 NPUAP/EPUAP (2009) Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Ulcers: Clinical Practice Guideline. NPUAP, Washington DC Perneger TV, Héliot C, Raë A-C, Borst F, Gaspoz J-M (1998) Hospital-Acquired Pressure UlcersRisk Factors and Use of Preventive Devices. Archives Internal Medicine, 158(17):19401945 Russell CA, Elia M (2008) Nutrition Screening Survey in the UK in 2007. http://bapen.org.uk/pdfs/nsw/nsw.07_report.pdf (accessed 24.11.08) Vanderwee K, Clark M, Dealey C et al Pressure Ulcer prevalence in Europe: a pilot study. J Eval Clin Pract. 2006;13:227-235. Author : Carol Dealey for BGS Policy Committee (June 2012) 6