Edgefield Syllabus

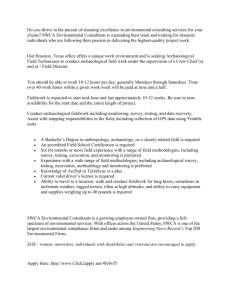

advertisement

Anthropology 454 and 455 George Calfas University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign gcalfas2@illinois.edu (217)766-6069 Field School Objectives: This class introduces archaeological field technique and outlines a critical understanding of the methods and approaches by which archaeological sites are interpreted. During the summer students will be involved in all phases of archaeology: archaeological survey, field excavation, and lab processing of artifacts. The course focuses on the Pottersville kiln site in the Edgefield District of South Carolina. The Edgefield Pottery District was at the epicenter of a ground-breaking stoneware alkaline glaze in the nineteenth century. To ensure a long term work force the Edgefield potteries utilized enslaved laborers to create the utilitarian vessels for the marketplace. Archaeological and Research Setting: Pottersville (38ED011) Pottersville is located in present day Edgefield County and it is the home to the world’s first alkaline glazed stoneware vessels. Pottersville is recognized as a nationally significant site based on historical, documentary evidence, and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places (NPS 2009). The Camden Gazette first wrote about the Pottersville vessels describing them as “the first of the kind” and “superior in quality” (C.G. 3 June 1819: 4-5). The quality of these vessels was later echoed by Robert Mills in his 1826 “Statistics of South Carolina” when he stated the stoneware was “stronger, better, and cheaper than any European or American ware of the same kind” (Mills 1826). Though the Pottersville manufacturing facility changed hands several times during its operation, it remained an integral site for stoneware manufacturing until closing in approximately 1843. Today, Pottersville is situated in an open pasture within one hundred meters of a modern road. A small stream is located four hundred meters to the east and a small pond approximately 1 km to the northeast. The kiln remains sit on the highest elevated point of the field, surrounded by a surface scatter of ceramic sherds in all directions. Schedule: Week 1 23-28 May: Orientation followed by fieldwork at the Pottersville site. Students will conduct geophysical surveys of the area kiln area to determine the placement of the archaeological units. Week 2-5 29 May- 25 June: Students will work in teams to excavate a specific portion of the kiln. This work will be based on geophysical surveys and soil test probes of the kiln site. Students will excavate according to standard archaeological techniques. Participants will receive training in how to prepare a site for excavation, excavate according to stratigraphy or "arbitrary" levels, describe the sediments and soils, perform detailed note taking, take accurate measurements, create scale drawings, learn field photography, and do mapping with a computerized laser transit and a highly accurate Global Positioning System. LiDAR data has been collected for 5-square miles around the Pottersville kiln site. Student teams will learn to interpret the maps and select sites for ground truthing. Pedestrian survey and shovel test pits will be utilized in efforts of located the dwellings of the enslaved African laborers. Any features discovered during this phase will be prioritized and excavated as time permits. Week 6 26 June-1 July: All archaeological units must be completely mapped prior to replacing soil. Students will work in teams of two in order to render the physical space onto two-dimensional graph paper. Once the site has been fully recorded all excavation units will be closed and refilled with soil. Suggested Field Equipment: Water bottle Sunglasses Sunscreen Bug repellant Camera and film Wide-brimmed hat Swimsuit Raincoat or poncho Hard soled work boots or work shoes, no sandals or flip-flops Clothing you don't mind getting dirty, including: long and short sleeved shirts; pants and shorts Toiletries Attendance: This course will only last six weeks, so missing one day is like missing a whole week during a normal semester. Obviously there may be circumstances like illness where you might be late or forced to miss a day. If you do wake up ill, you're expected to notify me. Sometime shortly after field school begins, I will distribute a list of everyone's room numbers. If you do miss a day for a legitimate reason, you will be allowed to make it up after the semester ends. All students who miss classes will receive an incomplete until those classes are made up. You absolutely must arrange make-up days with me before the end of the semester: if you do not arrange makeup days at the end of the semester, you will penalized a letter grade for every day you miss. All incompletes automatically become F's in a year. Promptness: The excavation day starts at 700a. Transportation will leave the hotel promptly at 630a. Same criteria holds for the public lectures. The field school students will arrive prior to the start of the lecture so we can meet community members and share the projects progress. Grading criteria: There are not papers or tests in this course, but there are certain expectations that must be fulfilled to receive a strong course grade. Grades are based upon the following: excavations, field lab, readings, and lecture attendance. Excavations consume the major portion of our time and contribute the most to your grade. Due to the heat in South Carolina we will conclude everyday washing artifacts; the field day will end once this task is completed. Everyone will be expected to follow the assigned readings and contribute actively to weekly discussions. Readings will focus our talks and those presented at the public lecture series. Due to the truncated time schedule attendance is paramount. You may miss time due to illness but remember one day away from the field site is equal to missing a week of classes on campus. Readings Readings will be utilized to guide evening discussion sections or serve as read ahead material for the public lecture series. Articles will be presented by a group of students; group size will be based upon the number of readings and will vary from week to week. Student groups will prepare their presentation and lead the discussion based on the reading, the archaeological project, and lessons learned about the discovered artifacts to date. I will provide PDF's of the readings prior to leaving for field school; these reading should be downloaded on a laptop you plan to bring with you or printed if you will not be traveling with a computer. *Reading list below* Excavation Unit Tours: Once each week, we'll go around the site as a group and each talk about the excavation unit we're digging. You should talk about what has been found, identify features, consider how that unit relates to other units on the site, and so on. Although these site seminars are intended to let us all know what's going on across the site, you should approach these talks as though you were explaining what you're doing to a nonarchaeologist. Think about how people who don't know excavation technique make sense of a site, and consider ways we can make it easier to understand what archaeologists do. Volunteers: We encourage people to volunteer as field excavators. After you've dug long enough to have an understanding of excavation, you will occasionally be assigned to work in an excavation unit with these folks. You will be expected to teach the volunteers to excavate and help them think about why we do archaeology. Most of these volunteers are from the Edgefield area, so they have a special interest in the work which we do. You should take advantage of their insights: consider what interests them about our work and think about how archaeology can more adequately address these interests. You should work with them as you would with any other member of the excavation team. Visitors: Site visitors and the media: During the summer we will sometimes have visitors, and it is possible those visitors may even include reporters from local newspapers or television. We will never turn away anyone who is interested in talking to us about the fieldwork, and we will have prepared handouts for folks who wish to take something away from the site. Obviously the way these people view and represent us is very important to the success of the project, so there are some basic things to keep in mind. Media: When visitors ask you questions--regardless of whether it’s a curious neighbor or The New York Times--don't say things off the top of your head. Off-the-cuff comments can cause us considerable grief, so think before you speak. To prepare you for such media encounters, we'll discuss what the project is interested in telling the community. You will not need to memorize a carefully worded statement, and on any given day you’ll have something different to show whoever shows up at the edge of your pit, but there are some things we want folks to understand about why we’re doing this particular dig. Keep in mind that whenever we are on the site, we represent the University and a long-term research project that needs community support and interest. Positive visitor experiences and media coverage are among the most effective forums we have for telling people about our research. Safety: An archaeology site is littered with sharp tools, deep holes, broken glass, rusty metal, and a variety of safety issues, so all students will be required to review our site safety protocol, which has specific directions regarding all site safety and behavior. A first aid kit is on site at all times containing basic supplies. Please take site safety seriously: in many ways this is no different than working on a construction site, so please help to make certain this is an injury-free summer. Working out in the Sun: Many of you will notice the spectacular glow your skin will display after a day or two of excavation time. Archaeology and a summer of digging will result in a fine tan, should this be what you desire. However, the sun can also make you truly miserable, and the long-term implications of sun exposure can be profoundly serious. Be sure to use sunscreen; don't worry about ruining your tan, because you're ensured plenty of ultraviolet exposure. Some folks like to wear a hat or bandanna to reduce summertime headaches -- you'll figure out what works for you. For those unfortunates who do burn or get singed in spots where the sunscreen was not liberally applied (e.g., ears, behind the knees, the crevice where your shirt creeps up your back, etc), be sure to cover those spots; few things can make your field school experience more miserable than layered sunburns. The heat and humidity will drain much of your physical and metal energy over days of digging. Be aware of the symptoms of heat exposure and monitor your friends. Heat exposure is a serious health threat, so drink plenty of fluids and rest when you are tired. If you are thirsty you are already dehydrated. Drink lots of water, occasionally spend time in the shade, and let us know if you don't feel good. Dress During the course of the field school we can expect visitors ranging from community members, reporters, and other interested parties. Consequently, there are some minor attire guidelines that will allow room for fashion statements without startling any of our visitors or the rest of us. Everybody must wear a shirt; tank tops are okay, but no exposed midriffs or swim suits. Always wear shoes with closed tops to protect your toes from shovels or falling buckets (i.e., no sandals or bare feet). Smoking: There will be no smoking permitted on site. Readings: Week 1 23-28 May: Castille, George J. (1988). Archaeological Survey of Alkaline-Glazed Pottery Kiln Sites in the Old Edgefield District, South Carolina. Report submitted to the South Carolina Department of Archives and History. McKissick Museum and South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC. National Park Service (2009). National Register of Historic Places. Pottersville, Edgefield County, South Carolina, Record No. 141573, National Register Information System No. 75001698, entered Jan. 17, 1975. National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service, Washington, DC., website http://nrhp.focus.nps.gov. Steen, Carl (1994). An Archaeological Survey of the Pottery Production Sites in the Old Edgefield District of South Carolina. Report submitted to the South Carolina Department of Archives and History. Diachronic Research Foundation, Columbia, SC. Week 2 29 May- 4 June: Holcombe, Joe L., and Fred E. Holcombe (1986). South Carolina Potters and Their Wares: The Landrums of Pottersville. South Carolina Antiquities 18(1&2): 47-62. Holcombe, Joe L., and Fred E. Holcombe (1989). South Carolina Potters and Their Wares: The History of Pottery Manufacture in Edgefield District’s Big Horse Section, Part I (ca. 1810-1825). South Carolina Antiquities 21(1&2): 11-30. Holcombe, Joe L., and Fred E. Holcombe (1998). Archaeological Findings. In "I Made This Jar . . ." The Life and Works of the Enslaved African-American Potter, Dave, edited by Jill B. Koverman, pp. 72-81. McKissick Museum, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC. Week 3 5-11 June: Horne, Catherine W., editor (1990). Crossroads of Clay: The Southern Alkaline-Glazed Stoneware Tradition. McKissick Museum, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC. Koverman, Jill B., editor (1998). "I Made This Jar . . ." The Life and Works of the Enslaved African-American Potter, Dave. McKissick Museum, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC. Koverman, Jill B. (1998). Dave's Verse as Social Response. In "I Made This Jar . . ." The Life and Works of the Enslaved African-American Potter, Dave, Jill B. Koverman, editor, pp. 82-92. McKissick Museum, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC. Week 4 12-18 June: Burton, Orville Vernon (1998). Edgefield, South Carolina, Home of Dave the Potter. In "I Made This Jar . . ." The Life and Works of the Enslaved African-American Potter, Dave, edited by Jill B. Koverman, pp. 39-52. McKissick Museum, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC. de Groft, Aaron (1998). Eloquent Vessels/Politics of Power: The Heroic Stoneware of "Dave the Potter." Winterthur Portfolio 33(4): 249-260. Week 5 19-25 June: Montgomery, Charles J. (1908). Survivors from the Cargo of the Negro Slave Yacht "Wanderer." American Anthropologist 10(4): 611-623, with a note by Frederick Starr. Newell, Mark M., and Peter Lenzo (2006). Making Faces: Archaeological Evidence of African-American Face Jug Production. In Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter, pp. 123-138. Chipstone Foundation, Milwaukee, WI. Thompson, Robert F. (1969). African Influence on the Art of the United States. In Black Studies in the University: A Symposium, edited by Armstead L. Robinson, Craig C. Foster, and Donald H. Ogilvie, pp. 112-170. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT. Vlach, John M. (1990b). International Encounters at the Crossroads of Clay: European, Asian, and African Influences on Edgefield Pottery. In Crossroads of Clay: The Southern Alkaline-Glazed Stoneware Tradition, edited by Catherine W. Horne, pp. 17-39. McKissick Museum, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC. Week 6 26 June-1 July: Joseph, J. W. (2007). One More Look into the Water -- Colonoware in South Carolina Rivers and Charleston's Market Economy. African Diaspora Archaeology Newsletter June, University of Illinois website, http://www.diaspora.uiuc.edu/news0607/news0607.html#2. South, Stanley (1991). Early Research and Publications on Alkaline-Glazed Pottery. South Carolina Antiquities 23(1&2): 43-45.