Disease Management - Botany and Plant Pathology

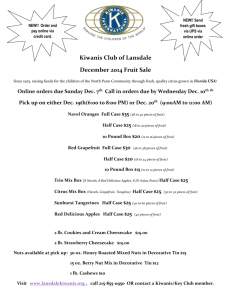

advertisement