Charisma Ying-Hin Liouh BA, California State

advertisement

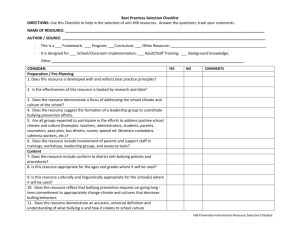

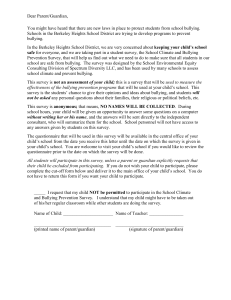

TEACHERS’ AND STUDENTS’ PERCEPTION OF BULLYING Charisma Ying-Hin Liouh B.A., California State University, Sacramento, 2005 THESIS Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATION at CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, SACRAMENTO SPRING 2010 TEACHERS’ AND STUDENTS’ PERCEPTION OF BULLYING A Thesis by Charisma Ying-Hin Liouh Approved by: __________________________________, Committee Chair Dr. Juliana Raskauskas __________________________________, Second Reader Dr. Sheri Hembree ____________________________ Date ii Student: Charisma Ying-Hin Liouh I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format manual, and that this thesis is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to be awarded for the thesis. __________________________, Graduate Coordinator Dr. Sheri Hembree Department of Child Development iii ___________________ Date Abstract of TEACHERS’ AND STUDENTS’ PERCEPTIONS OF BULLYING by Charisma Ying-Hin Liouh The aim of this study was to explore teachers’ and students’ perceptions of bullying. Surveys assessing teachers' and students' perceptions of bullying were administered at two middle schools in Sacramento, California across 43 seventh grade students and six of their teachers. Results showed a significant difference in teachers’ and students’ perceptions of the Personal Characteristics of Bullies/Victims. Results for males’ and females’ perception of bullying were also presented and discussed. The results are discussed in relation to Bronfenbrenner’s theoretical viewpoint and practical implications for teachers and students. _______________________, Committee Chair Dr. Juliana Raskauskas _______________________ Date iv DEDICATION I would like to dedicate this piece of work to the following people who believed in me: To my parents Farm On Liew and Ta Hin Saeliew for inspiring, supporting, guiding, and encouraging me to pursue higher education. To my husband Nai Jow Bienh, my love, for supporting me in completing my Master’s Degree. To my son Marc Liouh Bienh, my pride and joy. To my little brother Ton Hin Saeliew for being my emotional support system. To my older brothers San Hin, Sou Hin, and Nai Hin for showing me that higher education is important. To all my nieces and nephews for keeping Marc entertained while I complete my degree. Charisma Ying-Hin Liouh v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Juliana Raskauskas for her unconditional support and guidance. I would also like to express my gratitude to Dr. Sheri Hembree who has helped me in the completion of this research study. Last but not least, I would like to thank the schools and students who participated in this study. vi TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Dedication……………………………………………………………………………......v Acknowledgments……………………………………………………………………….vi List of Tables……………………………………………………………………………..x Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………….…..1 Purpose of the Study………………………………………………………….…...1 Statement of the Problem …………………………………………………….…...1 Significance of the Study………………………………………………………….3 Methods…………………………………………………………………………...4 Definition of Terms……………………………….……………………………….5 Limitations………………………………………….……………………………..5 Organization of the Thesis……………………………….………………………..6 2. LITERATURE REVIEW………………………………………………………………8 Bullying…………………………………………………………….……………..8 Effects of Bullying……………………………………………………….10 Theoretical Framework…………………………………………………..12 Roles of Attitudes about Bullying………………………………………..15 Teachers’ and Students’ Perception of Bullying………………………...16 Factors Contributing to Bullying……………………………………………..… 17 vii Characteristics Associated with Bullies……………………………...….18 Characteristics Associated with Victims………………………………...18 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………….20 3. METHODOLOGY……………………………………………………………………22 Purpose of the Study……………………………………………………………..22 Design of the Study……………………………………………………………....22 Participants…………………………………………………………………….…23 Data Sources and Instruments…………………………………………….……...24 Definition of Bullying……………………………………………………24 Perception Items……………………………………………………….…25 Developing Factors………………………………………………………………25 Procedures…………………………………………………………………….….27 4. RESULTS………………………………………………………………………….….28 Agreement on Perceptions……………………………………………………….28 Group Comparisons……………………………………...………………………30 Teacher versus Student…………………………………………………..30 Gender Comparison……………………………………………………...31 5. DISSUSION…………………………………………………………………………..33 Agreement on Perceptions……………………………………………………….34 Theoretical Framework…………………………………………………………..35 Implications……………………………………………………………………....38 viii Limitations and Future Research………………………………………………...39 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………….40 Appendix A. Questionnaires……………………………………………………………..42 References…………………………….………………………………………………….47 ix LIST OF TABLES Page 1. Table 1 Perception Items ..............………………………………………….…...26 2. Table 2 Percentage of Agreement with Items for each Respondent Group..........29 3. Table 3 Mean Numbers and Standard Deviations for Males and Females of Factors...................................................................................................................32 x 1 Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION Purpose of the Study Bullying among children and adolescents is a growing concern among educators and parents. The purpose of the present study was to examine teachers’ and students’ perceptions of bullying including the behaviors, risk factors, attitudes, and the effects of bullying. Seventh-grade students’ and their teachers’ knowledge were compared and gender differences examined. Statement of the Problem Bullying has been identified as a serious problem that is pervasive in homes and schools (Nesdale & Scarlett, 2004). Bullying in schools has been the focus of many studies over the last three decades (Dussich & Maekoya, 2007; Espelage & Swearer, 2003; Gini, 2004; & Pikas, 2002). Although bullying has been widely investigated with students, adults have limited knowledge on bullying (Frisen, Jonsson, & Persson, 2007). Research studies have indicated that children often do not agree with adults on what behaviors should be regarded as bullying or how to address it (Boulton, Bucci, & Hawker, 1999; Stockdale, Hangaduambo, Duys, Larson, & Sarvela, 2002). This is a 2 serious issue because adults are often the first line of intervention when bullying problems arise. Being bullied has been linked to future social and emotional problems in children (Crick, 1996; Crick & Bigbee, 1998) so it is important to be able to build consensus about perceptions of bullying between adults and students in order to design effective interventions. Since educators are often the adult most in a position to help students who are being bullied it is important to examine their perceptions of bullying and attitudes about bullies and victims. There is currently a lack of research comparing teachers’ and students’ perceptions of bullies and victims. Discrepancies between student and teacher perceptions of bullying may make it difficult for teachers to recognize bullying and understand victims. Without awareness of what children are at risk it is harder for educators to identify and assist students who are being bullied. Many students report that teachers are typically unaware of bullying that occurs at school or have stereotypes that are inconsistent with reality (Boulton, Bucci, & Hawker, 1999; Kockenderfer-Ladd & Pelletier, 2008). Therefore, it is essential to conduct research that compares teachers’ and students’ perception of who is bullied, who bullies, and why. It is also important to investigate teachers’ and students’ understandings about risk factors and effects of bullying because it may contribute to teachers’ willingness to intervene. Investigations of discrepancies between teachers’ and students’ beliefs can contribute to staff training on how to recognize and deal with bullying occurring at school. The present study intends to examine teachers’ and students’ perceptions of bullying, specifically ratings of bullying behaviors, characteristics, attitudes, and effects. 3 Significance of the Study A review of previous research studies has confirmed that both the bully and the victim have certain characteristics that are linked to bullying (Batsche & Knoff, 1994; Floyd, 1985; Frisen et al., 2007; Loeber & Dishion, 1984; Olweus, 1999). However, most studies fail to investigate the causes of bullying through the views of the students and the teachers. Such investigation is essential in order to evaluate bullying participants effectively. More than 60% of students involved in bullying report that school staff members respond poorly to bullying problems occurring in school (Batsche & Knoff, 1994). If teachers are educated in the area of bullying, they would be more than likely to intervene because they would have the knowledge of how to identify and handle a bullying situation. Appropriate adult intervention can reduce bullying (Frisen et al., 2007). Boulton, Bucci, and Hawker (1999) noted that several research studies have indicated that many children do not agree with the view of adults on certain types of behavior that should be regarded as bullying. To further support this argument, Frisen, Jonsson, and Persson (2007) explored the issue of bullying by using data collected from open-ended questionnaires to explore why children and adolescents become the victim and why they become the bully. This study explored adolescent’s perception of bullying, but failed to incorporate measures of adults’ perceptions of bullying. While many studies have been conducted on how bullying situations arises, there is a need for research investigating both the teachers’ and students’ perception of bullying to better understand 4 the key causes of bullying. This study was significant because it adds to the field by providing information on discrepancies between teachers’ and students’ perception of bullies, victims, and correlates. Methods In order to understand how bullies choose their victims and how children become the bully through the views of the students and their teachers a purposive sample of 7th grade students and their teachers were given self-report surveys on perceptions about bullying. Student and teacher responses regarding bullying were compared. Participants included 43 seventh grade students and six seventh grade teachers from two middle schools in Sacramento, California. At each school four co-occurring classrooms were randomly selected and all students in those classrooms were invited to participate. Student participants were 12 to 14 years (M = 12.5, SD = 0.6) and teachers ranged in age from 27 to 62 years old (M = 41.6, SD = 14.5). Consent letters were sent home with students to their parents/guardians explaining the purpose of the research. The instruments provided to the participants were self-report surveys designed for this research. They included instructions, a definition of bullying, demographic items and 41 statements on which participants rated their agreement. They included items on who gets bullied, why kids are bullied, attitudes to bullies, gender/ethnic differences, and how to make bullying stop. Items were based on the findings of Frisen, Jonsson, and Persson (2007), who identified common themes 5 characterizing bullies, victims, and attitudes from opened ended questions asked of high school students. The data were examined for similarities and the differences of teacher’s and students’ beliefs on the causes of bullying. Descriptive percentages were calculated for answers to key items on students’ and teachers’ percentages and compared. A factor analysis was used to identify key themes among the items and correlational analyses further tested the relationships between those variables within groups. Finally, t-tests were used for comparing students and teachers on key themes. Definition of Terms In order to identify behaviors, it is important to understand the term “bullying.” Bullying is a repeated aggressive behavior, physical, verbal, or psychological, that intentionally causes hurt to the recipient by an individual or a group that is unprovoked by the victim (Olweus, 1993; Woodhead, Faulkner, & Littleton, 1999). Limitations It is important to note the limitations of this study. There are four limitations that should be highlighted. First, the sample size was small, especially for teachers, and samples were not drawn from diverse population in a widespread environment which limits external validity. With a small sample size, the findings in this research cannot be 6 considered representative of seventh grade students or seventh grade teachers perceive bullying to be. Since the sample was non-random findings should not be generalized beyond the current context. Since the sample was drawn from only two schools within Sacramento area, it lacks input from students in other location. Second, due to some reading level differences survey questions were read and explained to some ESL (English Second Language) students in their native language by their teachers. Bias may exist in the sample because these students received the information differently than those who read and completed the survey on their own. Third, the surveys were collected following Star Testing week. Students may or may not answer the survey question to the best of their knowledge because they may be overwhelmed by school testing. Finally, the factor analysis identified nine factors, but only three factors had acceptable internal reliability. This limited conclusions that could be made and the utility of the survey data. Organization of the Thesis The current chapter provided an overview of the study. Chapter 2 is a review of the literature in the areas of bullying, the overlap between students’ and teachers’ perceptions, and the theoretical framework for this study. Chapter 3 explains the methods used in this research. Chapter 4 will provide an overview of the data analyses used to address the hypothesis, and the results of these analyses. The hypothesis being analyzed is that teachers and students will perceive a relationship between personal characteristics (e.g., small, short, weak) and bullying behavior differently. Finally, Chapter 5 7 summarizes the findings, describes the limitations, and provides suggestions for further research. 8 Chapter 2 LITERATURE REVIEW The purpose of this chapter is to provide a literature review to support the examination of any similarities and the differences in teachers’ and students’ perceptions of bullying. This review provides the reader with background information on the definition of bullying, the effects of bullying, and reviews the existing literature about attitudes about bullying. Similarly, broad profiles of the types of bullying and the characteristics of the bullies and the victims are presented. Gaps in the existing research regarding the teachers’ and students’ perception of bullying will be identified and presented along with a theoretical framework helpful for understanding bullying and people’s perceptions of it. Bullying Bullying is defined as a repeated aggressive behavior, either physical or psychological, that intentionally causes hurt to the recipient by an individual or a group that is unprovoked by the victim (Woodhead, Faulkner, & Littleton, 1999). Olweus (1993) proposed that bullying is a repeated negative action to which a person is exposed to by one or more students. A negative action occurs when a person intentionally inflicts injury or discomfort upon another person through means of physical contact or words. 9 Actions are not considered bullying if students of equal strength fight or disagree because bullying involves a power imbalance. Thus, bullying is a repeated aggressive behavior intentionally causing hurt or discomfort toward another by means of physical or verbal contact that is characterized by a power imbalance such that it is difficult for the victim to make the bully stop. Nansel et al. (2001) measured the prevalence of bullying behaviors among 15,686 sixth through tenth grade students in public and private schools throughout the United States. It was reported that 29.9% were involved in moderate to frequent bullying. The prevalence of bullying has been found to be highest among middle schools populations (Eliot & Cornell, 2009; Nansel et al., 2001). These statistics indicate that bullying is a huge problem in the United States and that special attention should be paid to middle school age students. Bullying behaviors are often classified into two sub types of bullying: overt (e.g., physical, verbal) and covert (e.g., relational aggression) (Crick, 1996; Crick & Bigbee, 1998; Crick & Grotpeter, 1995). Overt bullying includes behaviors that go directly from the bully to the victim and traditionally do not involve other people. The most common forms of overt bullying include physical aggression (e.g., hitting, kicking, biting) and verbal aggression (e.g., teasing, taunting, name calling) (Crick & Bigbee, 1998; Crick & Grotpeter, 1995). Covert aggression, on the other hand, includes the use of indirect means to harass another. Crick and colleagues have dubbed the main form of covert bullying as “relational aggression” (Crick, 1996; Crick & Bigbee, 1998; Crick & Grotpeter, 1995). 10 Relational aggression involves harming others through hurtful manipulation of peer relationships or friendships (Crick & Bigbee, 1998). This type of aggression includes malicious gossip, social exclusion, rumor spreading, and manipulation (Crick, 1996; Werner & Nixon, 2005). Gender differences have been found between covert and overt bullying. Although both genders will engage in both types, boys are more likely to use primarily overt bullying while girls are more likely to engage primarily in covert (Crick & Grotpeter, 1995; Espelage & Swearer, 2003; Olweus, 1993). Research indicates that girls use more covert bullying because relational aggression is more effective for girls’ tight-knit peer groups than males’ less intimate peer groups (Crick, 1996; Crick & Grotpeter, 1995; Simmons, 2002). Girls also place more importance on popularity and social comparison than males during adolescent years. Therefore, the threat of or actual loss of connection to peer group or popularity that characterizes relational aggression can be especially devastating to girls. Simmons (2002) concluded from her research with adolescent girls that peer groups can turn on a member without warning and resulting exclusion can negatively affect them (Simmons, 2003). Effects of Bullying Research indicates that all forms of bullying can produce social and emotional problems in children (Bond, Carlin, Thomas, Rubin, & Patton, 2001; Crick, 1996; Crick & Bigbee, 1998; Crick, Casas & Mosher, 1997; Crick, Ostrov, & Werner, 2006; Werner & Nixon, 2005). Cumulative evidence has shown that bullying has acute consequences 11 ranging from suicide, murder, absenteeism at school, and medical conditions such as faints, vomiting, paralysis, hyperventilation, limb pains, headaches, visual symptoms, stomachaches, fugue states, and long-term psychological disturbances such as anxiety, depression, loneliness, and hysteria (Bond et al., 2008; Espelage & Swearer, 2003; Olweus, 1993; Stockdale et al., 2002). Gender differences have been found in the types of effects reported by victims. Boys who are victims are at a greater risk of acting out and delinquency as young adults while girls who are victims have a greater risk of experiencing poor mental health such as peer rejection, anxiety, depression, and isolation (Bond et al., 2008; Crick, 1996; Crick & Grotpeter, 1995). Therefore, bullying is a serious concern and without intervention the effects are likely to worsen over time (Crick, 1996; Espelage & Swearer, 2003; Olweus, 1993). Types of bullying can also make a difference in effects. Crick (1996) conducted a study with 245 children in 3rd through 6th grade from two elementary schools. At these two schools, she assessed aggression, pro-social behavior, and social adjustment three times during the academic year using a peer-nomination measure. Results indicated that students who experienced relational aggression were most at risk for future adjustment problems (Crick, 1996; Crick & Grotpeter, 1995). Physical bullying, on the other hand, is most strongly associated with physical injuries and anxiety, while verbal bullying is associated most with reductions in self esteem and increased depressive symptoms (Bond et al., 2001; O’Moore & Kirkham, 2001; Seals & Young, 2003). 12 Theoretical Framework Bronfenbrenner (1995) proposed that human development occurs through “reciprocal interaction” between individuals (e.g., parent-child activities, student-student activities) on regular basis over the course of time. The interaction between the individuals may have contributed to the individuals’ behavior. For example, a boy who sees his father being aggressive (e.g., hitting, kicking) to his vulnerable mother on a regular basis may be influenced by his father’s aggressive behavior. The boy may become aggressive to his peer/s at school. In addition to living with an abusive father the boy may have also been interacting with his environment (e.g., television). Bronfenbrenner also states that human development can occur through interaction with the environment. If the boy above also chooses to watch violent movies and continue to be exposed to violent on regular basis the boy may start or continue to bully at school. Research shows that it’s important to consider all levels of the social ecology (e.g., school, family, community) to understand bullying (Espelage & Swearer, 2003). Urie Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Model is composed of five socially organized subsystems that help illustrate teachers’ and students’ perception of bullying and why they are important (Bronfenbrenner, 1994; Espelage & Swearer, 2003). The five subsystems are microsystems, mesosystems, exosystems, macrosystems, and chronosystems. The microsystem contains the individual who exists within the microsystem in a face to face interaction. Examples of these include family, school, peer group, and 13 workplace. Students are mostly affected by their family, their school life, and their peer group which would affect their perceptions of bullying. Teachers’ perceptions of bullying are also affected by their family, their school, their peer group, and their workplace (Bronfenbrenner, 1994). The second subsystem, the mesosystem, is comprised of the links between the microsystem. For example, the relations between the parents and teachers that influence the child's development. In this subsystem, Bronfenbrenner states that family and school have greater effect than those attributable to socioeconomic status or race. This means that both teachers and students perceptions of bullying would be affected by their family and school environment. For example, students would be influenced by how their families and peers at school view bullying and teachers would be influenced by how their families and their colleagues at school view bullying (Bronfenbrenner, 1994) The exosystem, the third subsystem in Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Model, is comprised of settings that do not contain the developing person, but indirectly influence the person through the micro- and mesosystems. For example, for the student, the parents’ employment decides how much supervision and research has shown that lack of supervision in the home has previously been associated with bullying (Batsche & Knoff, 1994; Olweus, 1993). This subsystem explains that students’ perceptions of bullying are influenced by their home life and the parent’s workplace. For example, the developing child may feel a sense of loneliness if his/her parents spends most of their time at work daily. For teachers, perceptions of bullying are influenced by their relation between the school and the neighborhood peer group. This explains that teachers’ perceptions and 14 attitudes of bullying are influenced by their school experience, policies, support from the administration, as well as the neighborhood where the school is and the population it serves. The macrosystem is the subsystem that consists of the overarching pattern of the microsystem, the mesosystem, and the exosystems. It is the history, culture, and laws surrounding the teachers and students that are influencing them (Bronfenbrenner, 1994). For example, the developing child's culture can contribute to the individual's perception about bullying. Minority children were more likely to report experiences with bullying than non-minority children (Soriano et al., 1994). In Bronfenbrenner’s model, these minority children were influenced by their culture to report bullying incidents. Teachers’ perception of bullying can also be influenced by the macrosystem. For example, if the teacher who enjoys teaching at a particular upscale school but was transferred to a lower scale school because of economic recession, this teacher might view bullying differently because of the exposure to the different environment and the changes in residence and employment. The last subsystem is the chronosystem. A chronosystem includes changes or consistency over time not only in the characteristics of the person but also of the environment in which that person lives. For example, changes over the life course in family structure, socioeconomic status, employment, or place of residence. Students’ perception of bullying can be influenced by chronosystem. For example, Espelage and Swearer (2003) state that the variables (e.g. race, sex, prior victimization) in the subsystem of the social-ecological model should be examine since they influence over 15 time. As Bronfenbrenner has suggested, cultures, family, and peer group change over time. Teachers’ and students’ perception of bullying today is different than it was 2 decades ago and it will continue to change slowly as more bullying research becomes more available. With more research available teachers and students come to recognized bullying as an issue (Espelage & Swearer, 2003). An application of Urie Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Model to bullying suggests that teachers’ and students’ attitudes about bullying would be influenced by their environmental contexts. Whether it is a day-to-day influence or over the course of time influence, teachers and students are influenced by their family, school, peer group, race, sex, prior victimization, internalizing psychopathology (Espelage & Swearer, 2003). These contexts would contribute to teachers’ and students’ perceptions of bullying. Role of Attitudes about Bullying With the high number of children involved in bullying across the United States, it is important to look at teachers’ and students’ attitudes about bullying. These attitudes pertain to how students perceive the characteristics of bullies. For example, is bullying appropriate, is bullying fair, and what are the characteristics of those involved in bullying? Biggs et al. (2008) found that students in classrooms with teachers who adhered to a bullying intervention program were seen by peers as more helpful to victims of bullying relative to students in other classrooms. This study also showed that students showed greater empathy and less involvement in bullying when teachers showed concern and willingness to intervene in bullying. This indicates that students’ attitudes about 16 bullying are related to their teachers’ attitudes about bullying because teachers who use the intervention in their classroom have students with greater empathy towards victims of bullying. Teachers’ and Students’ Perception of Bullying Although bullying has been widely investigated, many adults have a very little knowledge on bullying or opportunities to witness this behavior (Frisen, Jonsson, & Persson, 2007). The results of Boulton, Bucci, and Hawker’s (1999) study indicate that many children do not agree with the view of adults on whether certain types of behavior should be regarded as bullying Teachers’ perceptions of bullying is important to consider in the research because teachers play an important role in the school environment and it's important to consider teachers in implementation of any prevention of intervention programs (Linares et al., 2009). In addition, most students report that bullying is most frequent within the school grounds (Espelage & Swearer, 2003; Olweus, 1993). Naylor and colleagues (2006) showed that 25% (N = 138) of teachers did not include in their bullying definitions: name calling, spreading rumors, intimidating by staring and taking other people’s belongings. Over 50% of these teachers did not include social exclusion, suggesting that teachers lack knowledge of bullying behaviors. More than 60% of students involved in bullying report that school staff members respond poorly to bullying problems occurring in school (Batsche & Knoff, 1994). If teachers are educated about bullying, specifically the risk factors, characteristics of those involved, behaviors, and effects, they may be more likely to correctly identify and intervene in bullying correctly. 17 Frisen and colleagues (2007) showed adults who intervene can stop bullying situations. Unfortunately 86% (N = 119) of students have little faith in adults’ ability to stop bullying. Therefore, it is essential to consider teachers’ perception of bullying in order to see whether it matches existing research as well as students’ own perceptions. It is important to consider students’ perceptions of bullying along with teachers’ because students and teachers have a reciprocal relationship in which they both play an important role in preventing and intervening in bullying (Linares et al., 2009). By gathering information on students’ perception of bullying, researchers are able to narrow down the key component of students’ beliefs of bullying. Gathering information would help researchers understand how each group (e.g., student, teacher) view key aspects of bullying. For example, key components included but not limited to the characteristics of bullies (e.g., family problems) and characteristics of victims (e.g., fat and short). Establishing effective communication and shared understanding between students and teachers is also necessary for coordination of reporting and intervention efforts (Sahin, 2010). Once researchers are able to understand teachers’ and students’ beliefs of bullying, they will be able to formulate effective bullying prevention and intervention. Factors Contributing to Bullying Bullying among children and adolescents has been a focus of many international studies over the last three decades (Espelage & Swearer, 2003; Nansel et al., 2001; Olweus, 2003). Research has identified characteristics common to bullies and victims and 18 these factors are described below. However, it is important to note that there is little existing research examining whether students or teachers agree with these factors. Characteristics Associated with Bullies Researchers have explored the issue of bullying by investigating the characteristics of the bullies and their victims (Floyd, 1985; Loeber & Dishion, 1984). In one study, variables such as parents’ lack of supervision, hostile behavior, and poor teaching and problem solving skill predicted bullying. By acting upon what bullies have developed from their parents, they feel a sense of security when they are exerting control by bullying other children (Batsche & Knoff, 1994). Simmons (2002) suggests that aggression is the “hallmark of masculinity;” it allows men to control their surroundings and to obtain peers’ respect for resisting authority, and acting tough, troublesome, dominating, cool, and confident. The bullies use their physical strength to gain superiority by bullying other children. Research does indicate that boys are more likely to be bullied than girls; however, victims are just as likely to be girls or boys (Espelage & Swearer, 2003; Olweus, 1993, Raskauskas & Stoltz, 2007). Characteristics Associated with Victims Batsche and Knoff (1994) found two types of victim (passive victims and provocative victims). Passive victims are described insecure and non-defensive versus provocative victims who are hot-tempered and retaliate when attacked. Bullies who choose insecure and non-defensive children to be their victims do so so that they can be 19 more in control. Bullies choose hot-tempered victims because provocative victims are restless and anxious and provide more of a response to reinforce the bullying such as yelling or crying. According to this investigation, characteristics of the children (e.g., insecure and hot-tempered) predict involvement as both victims and bullies. Other research indicates associations between personal characteristics and being bullied and victimized. For example, shorter children are at higher risk of being bullied than tall children (Voss & Mulligan, 2000). Frisen, Jonsson, and Persson (2007) collected data from open-ended questionnaires of 119 adolescents aged 15 to 20 years. Frisen et al. (2007) found that 40% of bullying is reportedly due to appearance (being different from peers such as being thin, fat, ugly or speaking/acting different) and 36% are due to behavior such as being anxious. For children who have been bullies, 28% are due to low self-esteem, 26% are due to feeling cool and in control, and 15% are due to problems. This contradicts findings by Olweus (1993) who reports that children with such characteristics are not at greater risk for being bullied than their classmates, but instead that bullies will use characteristics that students are sensitive about to bully. Still, the real or perceived victimization for characteristics like being fat, red-haired, wear glasses, or speak in an unusual dialect are a risk factor for depression. (Batshe & Knoff, 1994; Frisen et al., 2007; Olweus, 1993). Most children feel that they cannot change the way they look (e.g., born with freckles) are more likely to feel helpless to stop bullying which may contribute to depression. Ethnicity is another important characteristic to examine. (Soriano et al. (1994) reported that minority children were more likely to report experiences with bullying than 20 non-minority children. Hanish and Guerra (2000) found that Hispanic children reported less bullying than either African American or Caucasian/Non-Hispanic children but other studies have found no significant differences (Siann, Callaghan, Glisson, Lockhard, & Rawson, 1994). Graham and Juvonen (2002) suggest that it is the ethnic composition of the school, rather than ethnicity of the individual, which predicts involvement in bullying. Moreover, some studies have found SES to be a better predictor of aggressive behavior than ethnicity (Hanish & Guerra, 2000; Patterson et al., 1990). Although research studies suggest ethnicity to have little effect in bullying involvement, ethnicity should not be ignored because it does seem to be associated with bullying in some studies. Conclusion The literature review presented described bullying, how it can affect students, and how the environment and behavior can both shape and be shaped by beliefs and attitudes. The review of literature shows that attitudes about bullying of students or teachers can be important in understanding bullying behavior and staffs willingness to intervene. However, there is a lack of research regarding teachers’ and students’ perception of bullying and the consistency between them. Based on the readings, bullying can contribute to severe damages (e.g., depression) and may even result in death (Crick, 1996; Crick & Bigbee, 1998). Readings also suggested that several bullying behaviors occur on school ground (Nesdale & Scarlett, 2004). Although these studies have indicated these results, it lacks research on 21 the individuals on school ground (e.g., students and teachers). The present study was formulated to examine similarities and differences in teachers’ and students’ perceptions of bullying. The hypothesis being examined is that teachers and students will perceive a relationship between personal characteristics (e.g. small, short, weak) and bullying behavior differently. 22 Chapter 3 METHODOLOGY In this chapter, study participants (e.g., male, female, teacher, student), definition of term, perception items, and data analysis will be described. The procedure and data sources will also be described. Purpose of the Study The purpose of this quantitative research study was to examine teachers’ and students’ perceptions of bullying, specifically ratings of bullying behaviors, characteristics, attitudes, and effects. A correlational study using self-report surveys was used to compare teachers’ and students’ perceptions. The intention behind the survey was to investigate similarities and differences about their beliefs about bullying between the two groups. Design of the Study The data were examined for similarities and the differences between teachers’ and students’ beliefs on the causes of bullying. Descriptive percentages were calculated for answers to key items on students’ and teachers’ percentages and compared by gender and 23 respondent (teacher and student). A factor analysis was used to identify key themes among the items and correlational analyses further tested the relationships between those variables within groups. Finally, t-tests were used to comparing students and teachers on key themes. Teachers and students were compared on their perceptions of personal characteristics and bullying behavior differently as well as perceiving the relationship between the motivations of bullying and the blaming of the victim. Participants The study group was comprised of 43 seventh graders and 6 teachers from two middle schools in the Sacramento County; 44.9% of participants came from one middle school and 55.1% of participants came from another middle school. Student participants were 12 to 14 years old (M = 12.5, SD = 0.6) and teachers ranged in age from 27 to 62 years (M = 41.6, SD = 14.5). Of the 49 participants, 61.2% were female and 38.8% were male. Of the 43 students 40% were male and 60% were female. Of the six teachers 33% were male and 67% were female. The two schools from which the samples were drawn were in an urban center in Northern California. Both schools were approximately the same size and serviced primarily lower income families. Students did not report on their own ethnicity or family income. However, demographic information for the schools as a whole were available from the district. School 1 had 836 students with 55 teachers participating in the study. This school body was comprised of 17.8% African American, 25.5% Asian, 47.3% 24 Hispanic, 6.0% white, 1.2% American Indian, 1.3% Pacific Islander, and 1.0% others. Of these 836 students, 87.0% were reported as socioeconomically disadvantaged in that they received free and reduced lunch. School 2 had 900 students with 48 teachers. This school was comprised of 25.2% African American, 0.2% American Indian, 40.3% Asian, 1.8% Filipino, 24.7% Hispanic, 2.8% Pacific Islander, 4.6% white, and 0.4% others. Of the 900 students, 99.0% socioeconomically were listed as economically disadvantaged in that they received free and reduced lunch. Data Sources and Instruments Using self-report surveys, data were collected from two middle schools. The instrument designed for this research included instructions, a definition of bullying, demographic items and perception items. Definition of Bullying A definition of bullying was provided to guide responses and ensure all students were using the same definition when making decisions about characteristics, motivations, and effects of bullying. The definition provided was “A repeated aggressive behavior which is negative that involves physical or verbal contact that intentionally causes harm to the victim which the victim is unable to defend him/herself.” 25 Perception Items Perception items included 41 statements in which participants rate their agreement. It also included items on student attitudes regarding who gets bullied, why kids are bullied, attitudes to bullies, gender/ethnic differences, and how to make bullying stop. Items were based directly on the findings of Frisen, Jonsson, and Persson (2007), who identified common themes about these items from opened ended questions asked of high school students. Participants rated their agreement on a 3 point scale: Disagree (0), Unsure (1), and Agree (2). This is a common format for bullying attitude questions that has been used in previous studies (Rigby, 1993; Smith, Pepler, & Rigby, 2004). Despite the fact that Frisen et al. created categories a priori, a factor analysis was used to develop categories from the data because this was the first time this survey was used and the original categories were developed based on responses of high school students. The measure is reproduced in Appendix A. Developing Factors To identify key themes or factors among the 41 perception items, a Factor Analysis with Varimax rotation was used and nine factors were identified. Of the nine factors found, six had Eigen values over 1.00 but only three factors had acceptable internal consistency. The three factors with acceptable consistency are described below and provided in Table 2. For each factor a mean score was calculated. 26 Factor 1 or Personal Characteristics of Bullies/Victims factor had eight items. The mean of the items was used to create the scale (M = 2.2, SD = 0.4, alpha = 0.8). Factor 2 or Motivation of Bullying had four items. The mean of the items was used to create the scale (M = 1.7, SD = 0.5, alpha = 0.7). Factor 3 or Blaming Victims had two items. The mean of the two items was used to create the scale (M = 1.8, SD = 0.7, alpha = 0.8). Items identified in the Factor Analysis were combined to create composite variables for comparison analyses. Table 1 Perception Items Factor 1 – Personal Characteristics of bullies Victims of bullying are usually fat. Victims of bullying are often considered ugly. Victims are mostly African American. Victims are mostly Hispanics. Victims are mostly Caucasian (white). Bullies are jealous of the victim. Bullies lack respect for other people. Bullies stop when they matures (get older). Factor 2 – Motivations for bullying Bullies are really cowards underneath. Bullies have psychological problems Bullies have family problems. Bullies have low self-esteem. Factor 3 – Blaming victims Bullies are annoyed by the victim’s appearance. Bullies are annoyed by the victim’s behavior. 27 Procedures There were two visits to the schools, one to announce the survey and hand out consent forms, and one to administer the survey approximately one week later. Consent letters were sent home with students to their parents/guardians explaining the purpose of the research. Students whose families gave permission for their participation in this study returned the signed consent form to the researcher. The child also completed an assent form on the day of the survey. Of the 49 consent letters returned, 44 parents/guardians allowed their children to participate. Of the 44 students who had permission to participate, 43 of them wished to sign the assent form and participated in the research study. Six teachers of the 43 students also participated in the study. The survey was administered in class by the researcher and the teacher. Those who did not have permission or did not wish to participate in the study sat quietly in their desks working on a class assignment independently. Teachers who participated in the research study completed the survey during the time that his/her classrooms were taking the surveys. Administration of the survey took approximately 20-30 minutes in each classroom. 28 Chapter 4 RESULTS In this chapter, the results are presented. The data are examined for key areas of difference between student and teacher perceptions as well as significant differences on factors derived from the data. Agreement on Perceptions The survey was examined for items where teachers and students differed on their agreement to the statements. Table 2 identifies the items which teachers and students have low agreements on. All teachers reported that bullies have psychological problems and family problems while only 47% of students reported that bullies have psychological problems and 37% of students reported that bullies have family problems. All of the teachers (100%) reported that victims of bullies are mostly Caucasian (white) and African American while 14% of students reported that victims of bullies are mostly African American and 19% of students reported that victims of bullies are mostly Caucasian. 33% of students reported that bullies will stop when they mature (e.g. get older) while none of the teachers reported that bullies will stop when they mature. The percentage of agreement between teacher and student on these items are very different. 29 Table 2 Percentage of Agreement with Items for each Respondent Group Item Male Female Victims of bullying are usually fat. 16% 7% 0% 9% Victims of bullying are often considered ugly. 21% 17% 33% 16% Victims are mostly African American. 16% 10% 100% 14% 5% 7% 17% 5% Victims are mostly Caucasian (white). 26% 10% 100% 19% Bullies are jealous of the victim. 21% 37% 17% 33% Bullies lack respect for other people. 58% 63% 85% 58% Bullies stop when they matures (get older). 26% 30% 0% 33% Bullies are really cowards underneath. 84% 40% 83% 53% Bullies have psychological problems. 74% 40% 100% 47% Bullies have family problems. 63% 33% 100% 37% Bullies have low self-esteem. 37% 17% 50% 21% Bullies are annoyed by the victim’s appearance. 32% 47% 33% 53% Bullies are annoyed by the victim’s behavior. 40% 33% 35% Victims are mostly Hispanics. 26% Teachers Students 30 Table 2 also shows differences of agreement on these items for males and females in the study on the perception items. Sixty-three percent of males agreed that bullies have family problems, 74% agreed they have psychological problems, and 84% agreed that bullies are cowards underneath. For females, 33% agreed that bullies have family problems, 40% agreed that bullies have psychological problem and are cowards underneath. Males and females percentage of agreement is very different. A higher percentage of males agreed that bullies have psychological problems, family problems, and that bullies are cowards underneath. Group Comparisons In order to address whether there are differences between teachers’ and students’ perception of bullying on the three factors (e.g., Personal Characteristics of Bullies/Victims, Motivation of Bullying, and Blaming Victims), a series of independent sample t-tests were conducted and are reported below. Gender differences were similarly examined. Means and Standard Deviations for group comparisons are presented in Table 3. Teacher versus Student To compare teachers and students perceptions of the Personal Characteristics of Bullies/Victims factor, an independent sample t-test was conducted. Teachers (M = 2.5, SD = 0.4) on average had higher scores on the perceptions of Personal Characteristics of 31 bullies and victims than students (M = 2.1, SD = 0.4) and this differences was statistically significant, t (47) = 2.1, p = .04, d = 1.0. To compare teachers’ and students’ perception on the Motivation of Bullying factor, another independent sample t-test was conducted. On average, students (M = 1.8, SD= 0.5) had higher scores on the motivation of bullying than teachers (M = 1.3, SD = 0.4) and that this differences was greater than expected by chance, t (47) = -2.2, p = .04, d = 1.1. An independent sample t-test was used to compare teachers’ and students’ perceptions of Blaming the Victims factor. However, this difference was not statistically significant, t (47) = 1.0, p = 0.3, d = 0.4. Gender Comparisons Three independent sample t-tests were conducted to compare males’ and females’ scores on the three perception scores (see Table 3). For the Bullies/Victims factor, females (M = 2.2, SD = 0.4) had slightly higher scores on the personal characteristics of bullies and victims than males (M = 2.1, SD = 0.5), but this difference was nonsignificant, t (47) = -.50, p = 0.6, d = 0.2. On the Motivation of Bullying factor, females (M = 2.0, SD = 0.5) had higher scores than males (M = 1.4, SD = 0.4) and this difference significant, t (47) = -3.4, p = .001, d = 1.3. Finally, while males (M = 1.9, SD = 0.6) had slightly higher Blaming the Victims scores than females (M = 1.8, SD = 0.7), this difference was also non-significant, t (47) = -.3, p = 0.7, d = 0.2. 32 These comparisons indicate that teachers often have different perceptions of bullying than students, such that more teachers agree that victims of bullies carry certain characteristics (e.g., ugly) and bullies have problems (e.g., family and psychological problems). Males have different perception of bullying than female, such that more males agree that bullies are cowards underneath and bullies have psychological problems. The following chapter will discuss these differences and why these findings are consistent with the previous research on bullying. Table 3 Mean Numbers and Standard Deviations for Males and Females of Factors ________________________________________________________________________ Factors Males Females ___________________ __________________ M SD M SD ________________________________________________________________________ 1. Personal Characteristics of Bullies/Victims 2.1 0.5 2.2 0.4 2. Motivation of Bullying 1.4 0.4 2.0 0.5 3. Blaming the Victims 1.9 0.6 1.8 0.7 ________________________________________________________________________ 33 Chapter 5 DISCUSSION Bullying among children and adolescents is a growing concern among educators and parents. Researchers agree that bullying has been identified as a serious problem in schools (Dussich & Maekoya, 2007; Espelage & Swearer, 2003; Gini, 2004; Nesdale & Scarlett, 2004; & Pikas, 2002). Although bullying has been widely investigated, adults have limited knowledge on bullying behavior and studies have indicated that children often do not agree with adults on what behaviors should be regarded as bullying (Boulton, Bucci, & Hawker, 1999; Frisen, Jonsson, & Persson, 2007). The present study explored the similarities and the differences in teachers’ and students’ perceptions of bullying. To explore any similarities and differences in teachers’ and students’ perceptions of bullying, the hypothesis was examined. The hypothesis was that teachers and students will perceive the relationship between personal characteristics (e.g. small, short, ugly, fat,) and bullying behavior differently. As expected, it was found that there is a difference. More teachers disagree with students that having certain personal characteristics promote involvements in bullying. Frisen et al (2007) found that 40% of bullying is reportedly due to their appearance (being different from peers such as being thin, fat, ugly or speaking/acting different). 34 Agreement on Perceptions When students and teachers were compared on agreement of their perceptions of victims, bullying, motivation, and the nature of bullying, differences were found. All of the teachers reported that bullies have psychological problems and family problems while less than half of the students reported that bullies have psychological problems and family problems. All of the teachers also reported that victims of bullies are mostly Caucasian (white) and African American and less than a fifth of students reported that victims of bullies are mostly African American and Caucasian. Teachers’ perceptions on which ethnic groups gets bullied the most are more consistent with existing research (Hanish & Guerra, 2000). A third of the students reported that bullies will stop when they mature (e.g., get older) while none of the teachers reported that bullies will stop when they mature. The percentages of agreement with bullying statements between teachers and students are very different. It is possible that students' agreement with teachers is low because students are the ones involved in bullying or witness bullying so they have a more realistic perspective. However, it is important to note that teacher's perceptions are more consistent with the existing research (Frisen et al., 2007). This research just looked at perceptions of bullies and victims not identification of specific bullying incidents. Frisen et al. (2007) found that many adults have opportunities to witness bullying behavior. When teachers do see bully behavior, they often don’t witness what started this behavior. These could be the reasons why Boulton et al. (1999) found that many children do not agree with the view of adults on specific bullying incidents. 35 More than half of the males agreed that bullies have family problems, psychological problems, and that bullies are cowards underneath, while half of the females agreed that bullies have family problem, psychological problem, and are coward underneath. Males and females percentage of agreement with these statements is very different with a higher percentage of males agreeing that bullies have psychological problems, family problems, and that bullies are cowards underneath. Males may endorse this statement because they are more likely to be involved in bullying than females. Researchers found that boys are more often involved in bullying than girls, both as bullies and victims (Farrington, 1993; Olweus, 1994). Theoretical Framework Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Model and Bioecological Model suggest that the developing child (e.g., students, teachers) can be influenced by the environment. These environments included but not limited to the developing child’s home, school, and family (Bronfenbrenner, 1994; Bronfenbrenner, 1995). The Ecological Model and Bioecological Model can help explain differences between students’ and teachers’ perceptions. In the microsystem, for example, Bronfenbrenner states that interactions in face-to-face settings such as family, school, peer group, and workplace. Students are mostly affected by their family, their school life, and their peer group which would affect their perceptions of bullying. 36 In the second subsystem known as the mesosystem is comprised of the links between the microsystem which includes the relations between the home and school, and the school and workplace. In this subsystem, Bronfenbrenner states that family and school have greater effect than those attributable to socioeconomic status or race. This means that both teachers and students perceptions of bullying were hugely affected by their family and school environment. For example, students were influenced by how their family and peers at school view bullying and teachers were influenced by how their family and their colleagues at school view bullying. More than half of the teachers disagree that having certain personal characteristics promote involvements in bullying while less than half of the students disagree. More teachers disagree with students that having certain personal characteristics causes bullying because students are the ones to experience bullying at school. The exosystem, the third subsystem in Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Model, is comprised of the effects of settings that does not contain the developing person, but does indirectly influence him/her. For example, for the student, the relation between the home and the parent’s workplace; for the teacher, the relation between the school and the neighborhood peer group. This subsystem explains that students’ perceptions of bullying are influenced by their home lives and the parent work settings. For the student, the parents’ employment decides how much supervision and research has shown that lack of supervision in the home has previously been associated with bullying (Batsche & Knoff, 1994; Olweus, 1993). It also explains that teachers’ perception of bullying are influenced by their school as well as the neighborhood peer group at where they live. More than half 37 of the teachers disagree with students that personal characteristics causes bullying and bullies are motivated to bully due to family problems and self-esteem. The macrosystem is the subsystem that consists of the overarching pattern of belief systems, bodies of knowledge, material resources, customs, life-styles, opportunity structures, hazards, and life course options that are embedded in each of these broader systems. The macrosystem includes history, culture, and laws, which means that teachers and students are also influenced by how their culture perceives bullying to be. The two schools where the data were collected were very diverse. Both of the schools were comprised of Hispanic, Asian, African American, white, American Indian, Pacific Islander, and others. Due to the schools’ diversity, the students and the teachers come from many various cultures with various perceptions on the characteristics and the motivation of bullying. The last and final subsystem is the chronosystem. A chronosystem include changes over time not only in the characteristics of the person but also of the environment in which that person lives. For example, changes over the life course in family structure, socioeconomic status, employment, or place of residence. Students’ perception of bullying can be influenced by chronosystem. Teachers’ perception of bullying can also be influenced by the chronosystem. Teachers and students differ on agreement of the characteristics associated with bullying and the motivation of bully because over time family structure changes, socioeconomic status changes, and employment changes. Teachers have more disagreements on the characteristics and the motivations of bullying because they may have worked at the school longer than the 38 students have been in school and they may have encounter multiple bullying situations that were not due to personal characteristics of the person. Bronfenbrenner’s Bioecological Model suggests that teachers and students’ perceptions of bullying are influenced by their interaction with their parents or peers (e.g., teacher-teacher activities, student-student activities, parent-child activities). These positive/negative interactions (e.g., loving parents, aggressive parents) could influence students’ and teachers’ perception on what they think are the motivations of bullying or the characteristics associated with bullying. Implications There are practical implications of these results for intervention or prevention strategies in schools. It is clear that teachers and students could agree upon not blaming the victims who involves in bullying but that they both disagree on the characteristics of the bullies and the victims and the motivation of bullying. This is a positive aspect for curriculum work and for policy development against bullying (Menesini et al. 1997). Schools can either use these results along with other related studies to create intervention/prevention strategies or conduct similar studies based on the current research study. The results of this study have provided information with regards to agreement between teachers’ and students’ perception about bullying that can help children (e.g., students) and adults (e.g., parents, teachers, principals, counselors, and other 39 professionals) have a shared understanding of bullying for creating a more effective bullying prevention and intervention programs. Limitations and Future Research It is important to note the limitations of this study. There are four key limitations, the first of which is the sample size, which was small across teachers and students. With a small sample size, the findings in this research were unable to represent what the average seventh grade students or seventh grade teachers perceive bullying to be. Samples were not drawn from diverse population in a widespread environment which similarly limits external validity. Since the sample was drawn from only two schools within Sacramento area, it lacks input from students in other location. Future research should collect data across multiple schools and across the states to ensure larger sample size and to ensure the data represents 7th graders and their teachers. Second, the fact that the survey procedures differed for a subset of students is a limitation. Survey questions were read and explained to some ESL (English Second Language) students in their native language by their teachers. Bias may exist in the sample because these students may receive the information differently than those who read the survey questions themselves. Future research should acquire a bilingual research assistant to help read and explain the survey questions to the students. Doing so will help eliminate how the questions are presented. 40 Third, the surveys were collected following Star Testing week. Students may or may not answer the survey question to the best of their knowledge because they may be overwhelmed by school testing. Future research should find out when schools are conducting Star Testing week and then either do the surveys 3-4 weeks before or after Star Testing. This would allow the students to become less overwhelmed. Finally, the perception survey based on Frisen et al.’s (2007) findings was shown to lack internal consistency. Six factors were found, but only three factors were reliability. Future research should create a better instrument that can discriminate student and teacher perceptions. Doing this may include using a five-point instead of three-point scale to show more variability. Unlike the present study, the instrument used in future research should be pilot tested. Future research should attempt to collect a larger and diverse population. Because data is best when collected towards the end of school at which students get more acquaintance with each other, future research should prepare to collect data for multiple years to insure a larger sample. Conclusion Many children do not agree with the view of adults on certain types of behavior that should be regarded as bullying (Boulton, Bucci, & Hawker, 1999). Despite the limitations this research may have, this research provides new information regarding teachers’ and students’ perceptions of bullying. The interesting finding here is that while 41 Frisen and colleagues (2007) pointed out that adults differ from students on their knowledge of bullying, the results of the current study indicate that teachers' perceptions were more in line with existing research. Findings show a need for perceptions to be examined more thoroughly to guide education and consensus around expectations for teachers and students. School based interventions for bullying are necessary since bullying is linked to future social and emotional problems in children and teachers are the first line of defense (Bond, Carlin, Thomas, Rubin, & Patton, 2001; Crick, 1996; Crick & Bigbee, 1998; Crick, Casas & Mosher, 1997; Crick, Ostrov, & Werner, 2006; Werner & Nixon, 2005). To further investigate teachers' and students' perceptions of bullying; future research should consider asking the following questions: "How are victims of bullies chosen?” “What should victims do to stop bullying?” “What are the signs of victimization?” Increased understanding of perceptions and beliefs about bullying may be important in ultimately changing future behaviors. 42 APPENDIX A Questionnaires Gender: ________ Age: ________ Circle one: _Teacher / Student__ Definition of bullying A repeated aggressive behavior Which is negative That involves physical or verbal contact Intentionally causes harm to the victim Which the victim is unable to defend him/herself. Please read each of the following sentences carefully and choose whether you agree or disagree with each one. Pick the answer that reflects whether you think these things are true about bullies and the victims of bullying. Circle the best answer. 1. Bullies are really cowards underneath. Your answer: Agree Unsure Disagree 2. Bullying is normal, everyone gets bullied. Your answer: Agree Unsure Disagree 3. Nobody likes a wimpy kid. Your answer: Unsure Disagree 4. It’s funny to see kids get upset when they are teased. Your answer: Agree Unsure Disagree 5. Victims of bullying are usually thin. Your answer: Disagree Agree Agree Unsure 43 6. Victims of bullying are usually fat. Your answer: Agree Unsure Disagree 7. Victims of bullying are often considered ugly. Your answer: Agree Unsure Disagree 8. Victims of bullying often talk or sound different. Your answer: Agree Unsure Disagree 9. Victims of bullying are shy. Your answer: Agree Unsure Disagree 10. Victims have low self-esteem Your answer: Agree Unsure Disagree 11. Victims come from poor families Your answer: Agree Unsure Disagree 12. Victims are mostly Asian. Your answer: Agree Unsure Disagree 13. Victims are mostly African American. Your answer: Agree Unsure Disagree 14. Victims are mostly Hispanics. Your answer: Agree Unsure Disagree 15. Victims are mostly Caucasian (white). Your answer: Agree Unsure Disagree 16. Victims have no friends. Your answer: Unsure Disagree Agree 44 17. Bullies think they are cool. Your answer: Agree Unsure Disagree 18. Bullies want to feel superior. Your answer: Agree Unsure Disagree 19. Bullies want to show that they have power. Your answer: Agree Unsure Disagree 20. Bullies have psychological problems Your answer: Agree Unsure Disagree 21. Bullies have family problems. Your answer: Agree Unsure Disagree 22. Bullies have low self-esteem. Your answer: Agree Unsure Disagree 23. Bullies bully others to feel better. Your answer: Agree Unsure Disagree 24. Bullies want to impress others. Your answer: Agree Unsure Disagree 25. Bullies are jealous of the victim. Your answer: Agree Unsure Disagree 26. Bullies lack respect for other people. Your answer: Agree Unsure Disagree 27. Bullies are annoyed by the victim’s appearance. Your answer: Agree Unsure Disagree 45 28. Bullies are annoyed by the victim’s behavior. Your answer: Agree Unsure Disagree 29. Bullies are also victims. Your answer: Unsure Disagree Unsure Disagree 31. Victims should changes schools to escape bullying. Your answer: Agree Unsure Disagree 32. Victim should stand up for himself/herself. Your answer: Agree Disagree Agree 30. Victims should changes classes to escape bullies. Your answer: Agree Unsure 33. Victim should become psychologically stronger to stop bullying. Your answer: Agree Unsure Disagree 34. Victim should stop being different (loses weight or gets the right clothes) if they want bullying to stop. Your answer: Agree Unsure Disagree 35. Bullies stop when they matures (get older). Your answer: Agree Unsure Disagree 36. Bullies become tired of bullying. Your answer: Agree Unsure Disagree 37. Bullies can find other victims. Your answer: Agree Unsure Disagree 46 38. Bullies feel a sense of guilt (realizes it’s wrong to bully others and feels badly) Your answer: Agree Unsure Disagree 39. Bullying stops when adults intervene (school, teachers, or others intervene) Your answer: Agree Unsure Disagree 40. Bullying stops if victims don’t care if they are bullied. Your answer: Agree Unsure Disagree 41. Bullying stops if victims of bullies can make new friends. Your answer: Agree Unsure Disagree 47 REFERENCES Batsche, G.M., & Knoff, H.M. (1994). Bullies and their victims: Understanding a pervasive problem in the schools. School Psychology Review, 23, 165-175. Biggs, B. K., Vernberg, E. M., Twemlow, S. W., Fonagy, P., & Dill, E. J. (2008). Teacher adherence and its relation to teacher attitudes and student outcomes in an elementary school-based violence prevention program. School Psychology Review, 37(4), 533-549. Bond, L., Carlin, J. B., Thomas, L., Rubin, K., & Patton, G. (2001). Does bullying cause emotional problems? A prospective study of young teenagers. BMJ, 323, 480-484. Boulton, M. J., Bucci, E., & Hawker, D. D. S. (1999). Swedish and English secondary school pupils’ attitudes towards, and conceptions of, bullying: Concurrent links with bully/victim involvement. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 40, 277-284. Bronfenbrenner, U. (1994). Ecological Models of Human Development. International Encyclopedia of Education, 3, 1643-1647. Bronfenbrenner, U. (1995). Developmental ecology through space and time: A future perspective. In P. Moen, G. H. Elder, Jr., & K. Luscher (Eds.), Examining lives in context: Perspectives on the ecology of human development (pp. 619-647). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Crick, N. R. (1996). The role of overt aggression, relational aggression, and prosocial in the prediction of children’s future social adjustment. Child Development, 67, 2317-2327. Crick, N. R., & Bigbee, M. A. (1998). Relational and overt forms of peer victimization: A multiinformant approach. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66 (2), 337-347. Crick, N. R., Casas, J. F., & Mosher, M. (1997). Relational and overt aggression in preschool. Developmental Psychology, 33 (4), 579-588. Crick, N.R., & Grotpeter, J.K. (1995). Relational aggression, gender, and socialpsychological adjustment. Child Development, 66, 710-722. Crick, N. R., Ostrov, J. M., & Werner, N. E. (2006). A longitudinal study of relational aggression, physical aggression, and children’s social-psychological adjustment. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 34 (2), 127-138. 48 Dussich, J., & Maekoya, C. (2007). Physical child harm and bullying-related behaviors: A comparative study in Japan, South Africa, and the United States. International Journal of Offender Therapy & Comparative Criminology, 51 (5), 495-509. Eliot, M., & Cornell, D. G. (2009). Bullying in middle school as a function of insecure attachment and aggressive attitudes. School Psychology International, 30 (2), 201-214. Espelage, D. L., & Swearer, S. M. (2003). Research on school bullying and victimization: What have we learned and where do we go from here? School Psychology Review, 32 (3), 365-383. Farrington, D.P. (1993). Understanding and preventing bullying. In M. Tonry (Ed.), Crime and justice (pp.381-459). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Floyd, N. M. (1985). “Pick on somebody your own size?” Controlling victimization. The Pointer, 29, 917. Frisen, A., Jonsson, A., & Persson, C. (2007). Adolescents’ perception of bullying: Who is the victim? Who is the bully? What can be done to stop bullying? Adolescence, 42 (168), 749-761. Gini, G. (2004). Bullying in Italian Schools. School Psychology International, 25 (1), 106-116. Graham, S., & Juvonen, J. (2002). Ethnicity, peer harassment, and adjustment in middle school: An exploratory study. Journal of Early Adolescence, 22, 173-199. Hanish, L. D., & Guerra, N. G. (2000). The role of ethnicity and school context in predicting children’s victimization by peers. American Journal of Community Psychology, 28, 201223. Kochenderfer-Ladd, B., & Pelletier, M. E. (2008). Teachers' views and beliefs about bullying: Influences on classroom management strategies and students' coping with peer victimization. Journal of School Psychology, 46 (4), 431-453. Linares, J., Diaz, A., Fuentes, M., & Acien, F. L. (2009). Teachers’ perception of school violence in a sample from three European countries. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 24, 49-59. Loeber, R., & Dishion, T. J. (1984). Boys who fight at home and school: Family conditions influencing cross-setting consistency. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 52, 759-768. 49 Menesini, E., Eslea, M., Smith, P. K., Genta, M. L., Giannetti, E., Fonzi, A., & Costabile. (1997). Cross-national comparison of children’s attitudes towards bully/victim problems in school. Aggressive Behavior, 23, 245-257. Nansel, T.R., Overpeck, M., Pilla, R.S., Ruan, W.J., Simons-Morton, B., & Scheidt, P. (2001). Bullying behaviors among US youth. Prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. American Medical Association, 16 (285), 2094-2100. Naylor, P., Cowie, H., Cossin, F., Bettencourt, R., & Lemme, F. (2006). Teachers’ and pupils’ definitions of bullying. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 76, 553-576. Nesdale, D., & Scarlett, M. (2004). Effects of group and situational factors on preadolescent children’s attitudes to school bullying. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 28 (5), 428-434. Olweus, D. (1993). Bullying at school: what we know and what can we do. Malden, MA: Blackwell. Olweus, D. (1994). Annotation: Bullying at school: Basic facts and effects of a schoolbased intervention program. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry, 35, 1171-1190. Olweus, D. (1999). Sweden. In P. K. Smith, Y. Morita, J. Junger-Tas, D. Olweus, R. Catalano, & P. Slee (Eds.), The nature of school bullying: A cross-national perspective (pp. 7-27). London: Routledge. O’Moore, M., & Kirkham, C. (2001). Self-esteem and its relationship to bullying behavior. Aggressive Behavior, 27, 269-283. Patterson, C. J., Kupersmidt, J. B., & Vaden, N.A. (1990). Income level, gender, ethnicity, and household composition as predictors of children’s school-based competence. Child Development, 61, 485-494. Pikas, A. (2002). New developments of the shared concern method. School Psychology International, 23 (3), 307-326. Raskauskas, J., & Stoltz, A. D. (2007). Involvement in traditional and electronic bullying among adolescents. Developmental Psychology, 43 (3), 564-575. Rigby, K. (1993). School children's perceptions of their families and parents as a function of peer relations. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 154 (4), 501-514. Seals, D., & Young, J. (2003). Bullying and victimization: Prevalence and relationship to 50 gender, grade level, ethnicity, self-esteem, and depression. Adolescence, 38 (152), 735-747. Siann, G., Callaghan, M., Glissov, P., Lockhart, R., & Rawson, L. (1994). Who gets bullied? The effect of school, gender, and ethnic group. Educational Research, 36, 123-134. Simmons, R. (2002). Odd girl out: The hidden culture of aggression in girls. New York: Harcourt. Smith, P.K., Pepler, D., & Rigby, K. (2004). Bullying in schools: How successful can interventions be? Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Soriano, M., Soriano, F. I., & Jimenez, E. (1994). School violence among culturally diverse populations: Sociocultural and institutional considerations. School psychology Review, 23, 216-235. Stockdale, M. S., Hangaduambo, S., Duys, D., Larson, K., & Sarvela. (2002). Rural elementary students’, parents’, and teachers’ perceptions of bullying. American Journal of Health Behavior, 26 (4), 266-277. Voss, L.D., & Mulligan, J. (2000). Bullying in school: Are short pupils at risk? Questionnaire study in a cohort. BMJ, 320, 612-613. Werner, N. E., & Nixon, C. L. (2005). Normative beliefs and relational aggression: An investigation of the cognitive bases of adolescent aggressive behavior. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 34 (3), 229-243. Woodhead, M., Faulkner, D., Littleton, K. (1999). Making sense of social development. New York: New York. Routledge.