An Empirical Study of the Toxic Capsule Crisis in China: Risk

advertisement

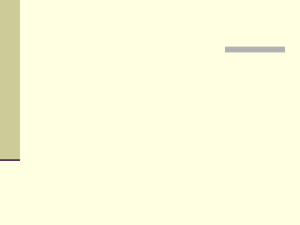

An Empirical Study of the Toxic Capsule Crisis in China: Risk Perceptions and Behavioral Responses Tianjun Feng tfeng@fudan.edu.cn School of Management Fudan University, Shanghai, P.R. China 200433 L. Robin Keller LRKeller@uci.edu The Paul Merage School of Business University of California, Irvine Irvine, CA, U.S.A. 92697-3125 Ping Wu 12110690016@fudan.edu.cn School of Management Fudan University, Shanghai, P.R. China 200433 Yifan Xu yfxu@fudan.edu.cn School of Management Fudan University, Shanghai, P.R. China 200433 6-22-2013 Forthcoming, Risk Analysis * Please address correspondence to L. Robin Keller (LRKeller@uci.edu). 0 ABSTRACT The outbreak of the toxic capsule crisis during April 2012 aroused widespread public concern about the risk of chromium-contaminated capsules and drug safety in China. In this paper, we develop a conceptual model to investigate risk perceptions of the pharmaceutical drug capsules and behavioral responses to the toxic capsule crisis and the relationship between associated factors and these two variables. An online survey was conducted to test the model, including questions on the measures of perceived efficacy of the countermeasures, trust in the State FDA (Food and Drug Administration), trust in the pharmaceutical companies, trust in the pharmaceutical capsule producers, risk perception, concern, need for information, information seeking, and risk avoidance. In general, participants reported higher levels of risk perception, concern, and risk avoidance, and lower levels of trust in the three different stakeholders. The results from the structural equation modeling procedure suggest that perceived efficacy of the countermeasures is a predictor of each of the three trust variables; however, only trust in the State FDA has a dampening impact on risk perception. Both risk perception and information seeking are significant determinants of risk avoidance. Risk perception is also positively related to concern. Information seeking is positively related to both concern and need for information. The theoretical and policy implications are also discussed. KEY WORDS: Toxic capsules; risk perception; behavioral response; pharmaceutical products; trust; structural equation modeling 1 Risk Perceptions and Behavioral Responses 1. INTRODUCTION In recent years, China has suffered from a number of food safety scandals, such as contaminated milk powder, swill-cooked dirty oil, tainted steamed buns, etc. Those crises have made the Chinese people more and more concerned about food safety issues and strongly weakened their trust in the food industry of China. Surprisingly, in 2012, the most influential safety-related crisis in China was not related to the food industry, but broke out in the drug industry. In April 2012, the toxic drug capsule crisis hit the headlines in China when the state broadcaster CCTV (China Central Television) reported that several capsule manufacturers in the Xinchang County of Zhejiang Province made and sold capsules with excessive levels of chromium after using industrial gelatin made from discarded leather.(1) Further investigations revealed that capsules made from industrial gelatin were in 13 commonly used drugs in the Chinese market, which were manufactured by nine domestic pharmaceutical companies, including the well-known Xiuzheng Pharmaceutical Group in Jilin province.(2) Those contaminated capsules contained more than 90 times the allowable upper limit of chromium, imposing a health hazard since chromium can be toxic and carcinogenic if ingested in excessive amounts.(3) Consequently, China’s State Food and Drug Administration (FDA) suspended sales of the 13 medicines with excessive levels of chromium, and the police arrested 22 people for making toxic drug capsules.(4) On August 4th, the State FDA announced that 76 local officials, employees of drug supervision agencies in five provinces and the municipality of Chongqing, had been punished because they had failed to prevent and stop the production of toxic drug capsules.(3) The toxic capsule scandal led to an immediate panic among the Chinese public. 2 Risk Perceptions and Behavioral Responses They were greatly worried about drug safety. Some expressed anger, such as “How can you make capsules from the broken shoes I threw away?”(3) Some of them strongly complained about the crisis, “This is ridiculous. people who are sick. Medicines are supposed to be safe and cure Those medicines are indeed toxic and may make patients even worse. What can we trust in this world?”(3) More people raised serious concerns about the responsibilities of the stakeholders involved in the scandal, e.g., “Can we still believe in those pharmaceutical companies?” “Can we still trust the regulation of the Food and Drug Administration, and other associated agencies?” etc.(3) Considering the reactions of the public, it is important to understand which factors have an influence upon risk perceptions and behavioral responses of this particular risk. There is abundant related research that studies risk perception and behavioral responses in various contexts, such as food safety,(5-10) product safety ,(11-13) pandemic or malignant diseases,(14-20) and natural hazards.(21-24) Drug safety has also been widely documented in the literature.(25-27) This stream of literature mainly focuses on the risk of drug use, including medical errors or misuse,(26,28,29) adverse events or experiences,(30,31) and adverse drug reactions.(32-34) However, to the best of our knowledge, no research has examined risk perception of toxic drug capsules. In this paper, we are interested in investigating how people perceive the risk associated with toxic drug capsules and what the determinants are of their risk perceptions and 3 Risk Perceptions and Behavioral Responses responses toward the crisis. A number of papers have employed structural equation models to examine factors affecting people’s risk perceptions and actions for different risks.(6,14,35-37) For example, by using the structural equation modeling method, Siegrist(36) explores the determinants of risk perceptions and acceptance of gene technology. Tanaka(35) extends Siegrist’s(36) framework to identify psychological factors affecting acceptance of gene-recombination technology using a structural equation model. Kuttschreuter(6) develops a structural equation model to explore the psychological determinants of the responses to food risk messages. Using structural equation modeling, Allum(37) studies the relationship between trust and risk perceptions of genetically modified food. Prati et al.(14) use a structural equation model to investigate cognitive, social-contextual, and affective factors influencing risk perceptions and responses to the pandemic influenza H1N1 (swine flu) in Italy. Following this stream of literature, this paper develops a hypothesized framework to determine the factors that have an impact on risk perceptions and responses to the toxic capsule crisis, based on a structural equation model. The paper is organized as follows. We first propose a conceptual model of risk perceptions of the toxic capsule crisis and behavioral responses to the crisis in Section 2. Next, in Section 3, we present our methodology. In Section 4, we report the main results. Finally, we provide a detailed discussion about the results as well as the limitations of this study and future research directions. 4 Risk Perceptions and Behavioral Responses 2. HYPOTHESIZED MODEL Many studies have explored the relationship between trust and risk perception.(36,38-44) Trust has been identified as one of the key predictors of people’s risk perceptions. For example, Freudenburg(45) argues that people who trust the abilities to safely dispose of nuclear waste in their country tend to have lower levels of perceived risk of nuclear waste. Siegrist(46) suggests that trust in institutions using gene technology is negatively associated with the perceived risk of this technology. Through an empirical investigation of the relationship between trust and risk perception in four European countries, Viklund(41) shows that trust is a significant determinant of perceived risk within countries. Kuttschreuter(6) provides empirical evidence that higher levels of trust in the safety of a product or an organization lead to lower levels of perceived risk. Furthermore, it has been documented in the literature that people have different degrees of trust in different parties, i.e., they trust consumer organizations, quality media and medical doctors the most, the food industry second, and government sources the least.(39) In the toxic capsule crisis, three major stakeholders were closely involved: the capsule producers, the pharmaceutical companies, and the State FDA of China. It is plausible to suspect that Chinese people have different levels of trust in those three stakeholders. As a result, in this study, we postulate that trust in the State FDA, trust in the pharmaceutical companies, and trust in the pharmaceutical capsule producers have a negative influence on risk perception. Perceived efficacy of countermeasures has been found to be an important factor affecting people’s trust in different organizations when they are faced with certain risks.(47-49) Through a laboratory study, Schweitzer et al.(50) find that a set of 5 Risk Perceptions and Behavioral Responses trustworthy actions can effectively restore people’s trust. Lewicki and Wiethoff argue that it is relatively easy to take some countermeasures to rebuild trust. (51) Dirks et al.(52) suggest that punishment and regulation of the transgressor have a positive impact on trust. Haselhuhn et al.(53) empirically show that people with incremental beliefs regarding moral character are more likely to trust their counterpart following trustworthy countermeasures. In recent years, China has experienced several crises related to pandemic diseases. For example, at the early stage of the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in 2003, the countermeasures by the government were unexpectedly slow and ineffective, resulting in dramatically decreased public trust in the authorities.(47) By contrast, during the outbreak of H1N1 in 2009, the central and local government agencies undertook appropriate actions quickly and effectively. As a result, the perceived efficacy of the countermeasures improved Chinese people’s trust in the government and corresponding institutions.(54) With respect to the toxic capsule scandal, the Chinese authorities adopted a series of countermeasures to deal with the crisis. According to the above discussion, we suggest that perceived efficacy of the countermeasures has a positive influence on trust in the State FDA, trust in the pharmaceutical companies, and trust in the pharmaceutical capsule producers during the toxic capsule crisis. Risk perception has been found to affect concern in a variety of contexts.(6,14,55,56) Specifically, through a study of the public’s reactions to the Chernobyl accident, Sjöberg(56) finds that risk is weakly positively associated with concern (e.g., worry). By surveying a group of military sailors prospectively during an international operation, Kobbeltved et al.(55) suggest that perceived risk has a positive impact on 6 Risk Perceptions and Behavioral Responses concern, such as worry. In the context of food safety, Kuttschreuter(6) provides empirical support for a positive relationship between risk perception and concern. Using a social-cognitive model of pandemic influenza H1N1 risk, Prati et al.(14) also find that risk perception positively influences concern. Therefore, we propose that risk perception has a positive influence on concern. The level of concern plays an important role in the process of information seeking.(57,58) People with worry or anxiety, which may cause a feeling of uncertainty, try to reduce the uncertainty or avoid exposure to the potential risks.(59) Griffin et al.(60) find that, among seven effects, concern (e.g., worry) influences people’s risk information seeking behavior. During the outbreak of the toxic capsule crisis, an individual who had taken capsule drugs recently might have worried about whether the capsule was toxic and how serious the harm of toxic capsules would be for his or her health. Then the individual might have sought various ways to obtain more information about the toxic capsule scandal and avoid the potential harm it might cause. Therefore, it seems plausible that concern has a positive influence on information seeking. Several papers have studied the information seeking process and how people react to risk information.(21,60) Atkin(61) posits that people pursue an amount of certainty that will make them comfortable about relevant topics. As the uncertainty increases, the need for information grows and thus information-seeking behavior arises.(61,62) On the other hand, Eagly and Chaiken(63) propose the Heuristic-Systematic Model (HSM), suggesting that people’s desire for sufficiency is the main driver for the information seeking process. On the basis of Eagly and Chaiken’s work, Griffin et al.(60) further develop the risk information seeking and 7 Risk Perceptions and Behavioral Responses processing model by adding a variable called “information sufficiency” (i.e., the gap between the information already held and the information needed). They find that when the information is not sufficient, people will seek added information to cope with the risk adequately.(60) Accordingly, we postulate that need for information has a positive influence on information seeking. According to the theory of planned behavior,(64-66) Griffin et al.(60) extend their risk information seeking and processing model to investigate preventive behaviors. Specifically, they show that an individual who seeks risk information more will exhibit more solid risk avoidance behaviors. Neuwirth(67) suggests that when people are faced with information about risk severity, they are more willing to take actions to avoid the risk. Similarly, in the context of health communication, Witte and Allen(68) find that when people are confronted with information about risk or danger, they may feel fearful and take adaptive risk control actions such as message acceptance and maladaptive risk control actions such as defensive avoidance. Therefore, we suggest that information seeking has a positive influence on risk avoidance. The relationship between risk perception and behavioral response to some specific risks has been extensively studied in the literature.(36,69-71) For example, Hammitt(69) reports that between conventional and organic produce, consumers perceive organically grown produce as having less hazardous risk and thus are willing Vernon(72) suggests that risk perception is to pay significantly more to purchase it. positively associated with preventive and protective cancer screening behavior. By conducting a longitudinal study, Brewer et al.(73) show that the behavior motivation hypothesis is supported, i.e., risk perception causes people to take protective actions. Through a meta-analysis study, Brewer et al.(70) provide additional evidence for the 8 Risk Perceptions and Behavioral Responses relationship between risk perception and behavioral response toward vaccination against infectious disease. Feng et al.(13) find that when people are faced with product quality risks, they are willing to pay more to purchase better quality products so that they can reduce or even avoid the associated risk. Prati et al.(14) indicate that people who have higher levels of risk perceptions of pandemic influenza H1N1 are more likely to adopt health-related recommendations to avoid the risk. Therefore, it is hypothesized that risk perception has a positive influence on risk avoidance. Based on the relationships hypothesized above, we develop a conceptual model to examine the determinants of risk perceptions and behavioral responses to the toxic capsule crisis, which is depicted in Figure 1. We present the methodology of the study in the following section. ……………………………………………………………….. Insert Fig. 1 here. ……………………………………………………………….. 3. METHODOLOGY 3.1 . Participants One hundred and ninety-three undergraduate students at a Chinese university in Shanghai participated in this study in May and June of 2012, right after the outbreak of the toxic capsule scandal. College student samples have been widely used in the previous research that studies risk perceptions and behavioral responses toward various contexts of risks.(36,35,74-76) In addition, when college students are sick, they are also likely to take capsule drugs by following doctors’ prescriptions and advice. For example, in this survey, approximately 22% of the participants reported that they 9 Risk Perceptions and Behavioral Responses had taken capsule drugs in the previous six months. Thus, it is appropriate to use a college student sample in this study. Qualtrix.com. Survey data were collected through Each student who had completed the online survey received a gift for participating. 3.2 . Instrument Development A questionnaire was designed to measure the relationship between the nine constructs for the conceptual model in Figure 1. Specifically, the measures for the constructs of risk perception, concern, and perceived efficacy of the countermeasures were adapted from Prati et al.(14) The constructs of information seeking, need for information and risk avoidance were assessed based on scales adapted from Kuttschreuter’s(6) work. To measure the three constructs in terms of trust in different stakeholders, we adapted the scales from Poortinga(42) and Kuttschreuter.(6) Participants were asked to rate, on a seven-point Likert-type scale, how much they agreed or disagreed with each statement in the questionnaire (i.e., 1=very strongly disagree to 7=very strongly agree). Before the formal study, we conducted a pilot test, during which respondents were asked whether they could clearly understand the questions and felt comfortable answering them. We continued to modify the questionnaire until it showed a fairly good content validity. Details of the questionnaire are provided in Table II in Section 4.1. 3.3. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations Table I presents the descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations of all the 10 Risk Perceptions and Behavioral Responses constructs. In particular, the participants reported high levels of concern (M=5.81), risk perception (M=5.58), and risk avoidance (M=4.91). The levels of information seeking (M=4.37) and need for information (M=4.12) were about average. The mean values of the remaining constructs were all below the midpoint of four, including perceived efficacy of the countermeasures (M=3.49), trust in the pharmaceutical capsule producers (M=3.76), trust in the pharmaceutical companies (M=3.00) and trust in the State FDA (M=2.82). With respect to the correlations between various constructs, there were significantly high associations between many constructs and no association between a few others (e.g., concern and need for information, r = 0.01). Given that there were sufficiently high intercorrelations for several pairs of the constructs, it is appropriate to conduct a principal component factor analysis to seek key underlying factors, which is presented in the next section. ……………………………………………………………….. Insert Table I here. ……………………………………………………………….. 4. RESULTS 4.1. Reliability and Validity Assessment To assess the reliability and validity of the questionnaire, we first conduct a principal component analysis (PCA) with a Varimax rotation to identify key factors underlying all the variables in the questionnaire by using the SPSS software package. From the PCA analysis, the variables are loaded onto the nine factors displayed in Table II. The eigenvalue of eight factors is greater than 1.0, and one factor has an eigenvalue of 0.913, which is acceptable. All the factors explain approximately 77% 11 Risk Perceptions and Behavioral Responses of the total variance, which is sufficiently high to account for the observed intercorrelations. construct. In addition, we calculate Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for each All alpha scores are satisfactory, with no values less than 0.80. Therefore, the scales of the questionnaire generally have high internal consistency reliability. ……………………………………………………………….. Insert Table II here. ……………………………………………………………….. Then we conduct a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) by creating a LISREL path diagram. The CFA shows an acceptable model fit. The normed χ2 (χ2 to degrees of freedom, χ2=681.44, d.f.=459) is 1.48, which is below the desired cut-off value of 3.0. The Standardized RMR (SRMR) is 0.054, which is below the desired cut-off value 0.10. Root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) is 0.051, which is lower than 0.08, indicating a good fit. The normed fit index (NFI=0.92) and comparative fit index (CFI=0.97) are both greater than 0.90. To summarize, the results suggest that the structural model has a good fit.(77) With respect to the convergent validity of the measures, first, all standardized path loadings are greater than 0.7 except items 3 and 4 under risk avoidance (0.68 and 0.69), item 5 under trust in the State FDA (0.63) and item 1 under need for information (0.68). According to Kim et al.(78), standardized path loadings should be greater than 0.7 and statistically significant. Thus, we dropped item 5 under trust in the State FDA from the model analysis and keep the other three items in the model because their standardized path loadings are nearly 0.7. that all standardized path loadings are significant. 12 In addition, t-tests reveal Second, Cronbach’s alphas(79) Risk Perceptions and Behavioral Responses should be larger than 0.7. In this study, all Cronbach’s alphas are greater than 0.8, which satisfies the requirement. Third, the average variance extracted (AVE) for each factor(80) should be greater than 0.5 and the composite factor reliability (CFR)(81) should be larger than 0.7. All AVE values are above 0.60 and the CFR is greater than 0.80. Therefore, the results suggest there is acceptable convergent validity of the measurement model. To check the discriminant validity of the measures, we first perform ordinary CFA analysis for every pair of factors, set the correlation of the two factors to 1.0, and then test the model again. According to Gerbing and Anderson,(82) the χ2 difference test is used to compare the results between the constrained model and the unconstrained model for every pair of the constructs. In this study, the χ2 differences are found to all be significant, which implies that the original model is better than each constrained model. Therefore, we establish the discriminant validity of the measurement model. 4.2. Structural Equation Model The conceptual model in Fig. 1 is tested using the LISREL software. The initial model depicted in Fig. 1 yields a good fit to the data (CFI = 0.97).1 However, according to the Lagrange Multiplier Test (LM Test), the addition of two causal paths significantly improves the fit of the new model, i.e., one path from trust in the pharmaceutical companies to trust in the State FDA, and the other from trust in the 1 Note that two causal paths are found to be non-significant, i.e., one path from trust in pharmaceutical companies to risk perception, and the other from trust in pharmaceutical capsule producers to risk perception. The results suggest that deletion of the two paths does not change the χ2 significantly (Δχ2 (2) = 2.14, p = 0.343). 13 Risk Perceptions and Behavioral Responses pharmaceutical capsule producers to trust in the State FDA. Specifically, the initial and the revised model are nested, thus, the difference in χ2 between the two models could be used for the evaluation of the improvement in fit of the new model.(36) As shown in Table III, the estimation of the revised model provides a significantly improved model, i.e., the χ2 decreases significantly (Δχ2 (2) = 18.13, p < 0.001). The results indicate that trust in the State FDA is influenced by both trust in the pharmaceutical companies and trust in the pharmaceutical capsule producers. In addition, the LM Test suggests that the addition of correlated errors of measurement provides a better fit to the data. However, post-hoc modifications with respect to correlated errors of indicator variables are problematic,(36,83) thus no additional parameters are relaxed in the model. ……………………………………………………………….. Insert Table III here. ……………………………………………………………….. Fig. 2 shows the standardized LISREL path coefficients and the overall fit indices for the test of the final model. Table II. The factor loadings of the final model are reported in For the final model, the updated normed χ2 (χ2 to degrees of freedom, χ2=675.07, d.f.=450) is 1.50, which is smaller than the desired cut-off value of 3.0. The Standardized RMR (SRMR) is 0.067, which is below the designed cut-off value 0.10. The root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) is 0.052, which is lower than 0.08, indicating a good fit. The normed fit index (NFI = 0.92) and comparative fit index (CFI = 0.97) are both greater than 0.90. suggest that the final model fits the data quite well. 14 Thus, the results Risk Perceptions and Behavioral Responses ……………………………………………………………….. Insert Fig. 2 here. ……………………………………………………………….. From Fig. 2, it can be seen that a small percentage of the variance in risk perception (3.7%) is explained. Among the three different trust variables, only trust in the State FDA (β = -0.24, t = 2.28) is found to have a significantly negative influence on risk perception. Trust in the pharmaceutical companies and trust in the pharmaceutical capsule producers are both found to be insignificant predictors of risk perception. However, these two trust variables have an influence on trust in the State FDA. That is, both of them have an indirect influence on risk perception, via trust in the State FDA. With respect to trust, a remarkable percentage of the variance in trust in the State FDA (51%) is explained, followed by trust in the pharmaceutical capsule producers (25%) and trust in the pharmaceutical companies (22%). Perceived efficacy of the countermeasures is found to be a significant determinant of trust in the State FDA (β = 0.46, t = 5.41), trust in the pharmaceutical companies (β = 0.47, t = 5.53) and trust in the pharmaceutical capsule producers (β = 0.50, t = 5.61), respectively. In addition, trust in the pharmaceutical companies (β = 0.26, t = 3.63) and trust in the pharmaceutical capsule producers (β = 0.16, t = 2.12) explain portions of the variance in trust in the State FDA. About 48% of the variance in concern is explained and risk perception is found to be a significant predictor (β = 0.70, t = 9.37). The variance of information seeking is explained to a lesser degree (27%). Both concern (β = 0.34, t = 4.59) and need for information (β = 0.40, t = 5.11) are found to significantly influence information 15 Risk Perceptions and Behavioral Responses seeking. Finally, a considerable percentage of the variance in risk avoidance (35%) is explained. Information seeking (β = 0.34, t = 4.26) and risk perception (β = 0.42, t = 5.13) are both found to be significant determinants of risk avoidance. 5. DISCUSSION In this paper, we investigated risk perceptions and behavioral responses to the recent outbreak of the toxic pharmaceutical capsule crisis in China. On the basis of the previous literature, we developed a conceptual model to explore the determinants of the public risk perceptions of the crisis and reactions to the crisis. An online survey was conducted to collect the data and test the conceptual model. In general, we found that participants did not trust the three major stakeholders during the crisis, including the State FDA of China, pharmaceutical companies, and pharmaceutical capsule producers. In addition, they perceived the countermeasures by the authorities to be relatively ineffective, i.e., people were generally not satisfied with the actions adopted by the government and corresponding agencies. Participants reported fairly high levels of perceived risk of the toxic capsules and concern about the risk. They had high levels of risk avoidance, i.e., they were willing to take actions to reduce the risk associated with toxic capsules. There were moderate levels of need for information and information seeking. We use the structural equation modeling method to test the proposed conceptual model and explore the relationships between the variables. The results suggest that the model depicted in Fig. 2 yields a good fit to the data. One of the most interesting results of this study is that among the three different trust variables, only trust in the 16 Risk Perceptions and Behavioral Responses State FDA is found to be a significant determinant of risk perception for toxic capsules, and the other two trust variables influence trust in the State FDA, rather than risk perception directly. As discussed previously, three major stakeholder groups are involved in the toxic capsule crisis. One is the pharmaceutical capsule producers which used industrial gelatin made from discarded leather to produce capsules and then sold them to pharmaceutical companies. The second one is the pharmaceutical companies which used toxic capsules to encapsulate drugs during their manufacturing process. The third stakeholder is the State FDA of China which is responsible for protecting and promoting public health through the regulation and supervision of food and drug safety in China. To compare the impact of trust in those three different organizations on risk perception of toxic capsules, we incorporated three trust variables in our model. Following the literature,(6,36,41) we hypothesized that risk perception is negatively related to each of the three variables, i.e., higher levels of trust in an organization generally leads to lower levels of risk perception. Surprisingly, the results suggest that only trust in the State FDA dampens risk perception of the toxic capsules, whereas trust in the pharmaceutical capsule producers and trust in the pharmaceutical companies have an indirect influence on risk perception via trust in the State FDA. We provide a possible explanation as follows. From the media reports, the ostensible cause of the toxic capsule crisis is that some firms illegally used industrial gelatin to produce capsules, and pharmaceutical companies might have intentionally purchased what turned out to be toxic capsules for the sake of cost reduction. However, the crisis revealed the regulatory gaps in the drug industry oversight by the State FDA of China, i.e., the current regulation and supervision rules for drug safety are far from perfect. 17 Such Risk Perceptions and Behavioral Responses imperfect regulation and supervision rules were arguably seen by the Chinese public as the root cause of the toxic capsule scandal. Because the public thought that the State FDA of China was mainly responsible for the crisis, they had lower levels of trust in the State FDA, resulting in higher levels of risk perception of toxic capsules. This is in line with the findings of the prior studies which investigated risk perception of pandemic diseases in China, such as SARS and H1N1.(47,84) In addition, the State FDA supervises and regulates the pharmaceutical industry, including the pharmaceutical companies and pharmaceutical capsule producers. It is intuitive that the two trust variables have a positive influence on trust in the State FDA. Therefore, the major insight of this result is that to reduce the public’s risk perception of drug safety in developing countries where the regulation rules or policies are not perfect, a potentially effective risk communication strategy might be to improve the regulation and supervision system and thus enhance public trust in the official agencies. Perceived efficacy of the countermeasures by the authorities has a positive impact on all three trust variables in the context of the toxic capsule scandal. This is consistent with the consequences of several previous major pandemic diseases in China. For example, the SARS epidemic originated from Southern China in November 2002, however, the Chinese government did not report its outbreak to the World Health Organization (WHO) until February 2003.(85) Due to a lack of openness, insufficient and delayed efforts had been devoted to control the spread of the epidemic at the early stages in China.(85) This in turn resulted in overwhelmingly lower levels of the public’s trust in the authorities during the outbreak of SARS.(47,49,54) In addition, trust is fragile, and once trust is destroyed, it is very difficult and time-consuming to rebuild.(44) In the case of the toxic capsules, the mean value of 18 Risk Perceptions and Behavioral Responses the perceived efficacy of the countermeasures is below the midpoint four, which implies that the public was not satisfied with the actions implemented by the authorities. This suggests that at the very early stage of the crisis, the authorities should have adopted timely and effective actions to improve people’s trust in the government agencies and corresponding organizations in the pharmaceutical industry. Furthermore, we observed that there is some difference in the degree of the impact of perceived efficacy of the countermeasures on the three trust variables. Specifically, perceived efficacy of the countermeasures has the largest effect on trust in the State FDA, compared to trust in capsule producers and trust in pharmaceutical companies. This is an intuitive result because the State FDA is an agency of the Chinese Ministry of Health, and is the most representative authority undertaking countermeasures during the crisis. The relationship between risk perception and concern has been widely documented in the literature.(6,14,55,56) Specifically, when studying the predictors of responses to food risk messages, Kuttschreuter(6) showed that risk perception has a weakly positive impact on concern. The impact was reported to be fairly strong in the context of pandemic influenza H1N1.(14) In line with these studies, we found that the perceived risk level had a strong influence on concern in the toxic capsule case. Therefore, it seems plausible to conclude that risk perception is an important determinant of concern in a variety of risky situations, including pandemic diseases, food and drug safety risks. To further investigate the potential difference in the degree of the influence of risk perception on concern among different health risks, a more general conceptual model could be developed and tested in future studies, based on prior studies and this 19 Risk Perceptions and Behavioral Responses research.(6,14,86) In such a general model, for each specific risk (e.g., food safety risk, pandemic influenza H1N1 risk, or toxic drug capsule risk), risk perception and concern would be determinants of behavioral responses to that risk. Both risk perception and concern would be influenced by cognitive (e.g., trust, perceived coping efficacy, etc.) and social-contextual factors (e.g., perceived governmental preparedness, level of development in country, etc.). In addition, under some circumstances, cognitive and social contextual factors might have a direct influence on behavioral responses, and background levels of other risks might affect perception of a specific risk. It is beyond the scope of this research to create and test such a general model considering several risks. Both concern and need for information were found to be significant determinants of information seeking in terms of the toxic capsule crisis. Note that the relationship between concern and information seeking was shown to be insignificant for the risk associated with a potential Salmonella or dioxin contamination of chicken in Kuttschreuter.(6) This suggests that concern significantly influences information seeking in the context of drug safety, but this may not be true in the context of food safety. On the other hand, according to the risk information and processing model by Griffin et al.,(60) the need for information is a key determinant of information seeking. For the public, the risk of toxic capsules was fairly novel. As a result, information insufficiency would induce people to seek information so that they could better deal with the risk of toxic capsules. Our results show that risk avoidance is predicted by both risk perception and information seeking with respect to the risk of toxic capsules. The prior literature suggests that risk perception is central to health behavior theories.(36,69-71) 20 Our Risk Perceptions and Behavioral Responses results conform to the health behavior theories in the sense that risk perception also has a significant positive impact on health behaviors in the context of drug safety risks. On the other hand, information seeking is found to be significantly positively related to risk avoidance when people were faced with the toxic capsule crisis. For example, for those who had to take capsule drugs, they could check online for the batch numbers of products found with excessive levels of chromium released by the State FDA and decide whether they needed to change the medicine.(3) Going to an extreme, to avoid the risk of ingesting toxic capsules, some Chinese consumers creatively worked out a 4-step do-it-yourself tutorial of how to wrap medicine by using a warm steamed bun to replace the capsule, and posted it on Sina’s Weibo.com, receiving tens of thousands of retweets within a day.(87) This study has several limitations. First, a student sample is used in this study. As discussed previously, it is appropriate to use college students to investigate risk perception and behavioral response to the risk of toxic capsules. However, there might be some difference between students and the general public, though we believe that it does not make the student sample less appropriate for our study. Second, the results suggest that the final model provides a good fit to the data. However, this does not imply that this is the only model that fits the data. Future research could test rival models that might better explain the data. Finally, an advantage of this study is that we focus on a parsimonious model which considers the primary relationships between the variables. However, a more general model may be considered in future studies. Such a more general model might have a higher explained variance in risk perception. Previous studies show that in addition to trust, risk perception can be affected by other factors, such as 21 Risk Perceptions and Behavioral Responses contemporary world views,(36) susceptibility to risk,(6) media exposure,(88) and mortality and morbidity risks to sensitive populations and perceived controllability by individuals or institutions.(89) Similarly, this study only considers perceived past performance (i.e., perceived efficacy of countermeasures) as a determinant of trust. According to the Trust, Confidence and Cooperation (TCC) model, both perceived past performance and perceived value similarity may influence trust.(90,91) In addition, Barber(92,93) argues that two factors constitute trust: the expectation of technical competence and the expectation of fiduciary responsibility. could examine the levels of these two components of trust. Future studies For example, to enhance trust, the State FDA could exhibit both technical competence and use its funds responsibly. Another example is that in this study, we only consider risk perception and information seeking as the determinants of risk avoidance. The classical Protection Motivation theory posits that risk avoidance can be influenced by a variety of factors, including the perceived severity of a risk, the perceived probability of the occurrence, the efficacy of the recommended preventive behavior, and the perceived self efficacy.(94) It would be interesting to incorporate some of those variables discussed above into a more general model to better explain risk perceptions and behavioral responses to the toxic capsule crisis in China. Acknowledgments We thank the area editor Michael Siegrist and two anonymous referees for their thoughtful and constructive reviews, which have helped significantly improve the article. Portions of this work were supported by grants to L. Robin Keller from the John S. and Marilyn Long U.S. - China Institute for Business and Law at the University of California, Irvine, and Tianjun Feng from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant 70901022), the Shanghai Philosophy and Social Science Planning Funds (Grant 2012BGL014), and the Ministry of Education of China (Grant for Overseas-Returnees). 22 Risk Perceptions and Behavioral Responses References 1. The-Telegraph. Chinese police arrest 22 over toxic drug capsules. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/asia/china/9208216/Chinese-police-arrest-2 2-over-toxic-drug-capsules.html, 2012. 2. Liu J. Capsule safety scandal to put prices up. China Daily, http://europe.chinadaily.com.cn/business/2012-05/14/content_15284096.htm, 2012. 3. Xinhua. Toxic capsules reignite concerns over drug safety. http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/business/2012-04/17/content_15070215.htm, 2012. 4. Xinhua. 22 nabbed for producing toxic drug http://www.china.org.cn/china/2012-04/17/content_25161446.htm, 2012. capsules. 5. Yeung RMW, Morris J. Food safety risk: Consumer perception and purchase behaviour. British Food Journal, 2001; 103 (3):170-187. 6. Kuttschreuter M. Psychological determinants of reactions to food risk messages. Risk Analysis, 2006; 26 (4):1045-1057. 7. Patil SR, Frey HC. Comparison of sensitivity analysis methods based on applications to a food safety risk assessment model. Risk Analysis, 2004; 24 (3):573-585. 8. Dosman DM, Adamowicz WL, Hrudey SE. Socioeconomic determinants of health- and food safety-related risk perceptions. Risk Analysis, 2001; 21 (2):307-318. 9. Jensen KK, Sandøe P. Food safety and ethics: The interplay between science and values. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 2002; 15 (3):245-253. 10. Van Kleef E, Houghton J, Krystallis A, Pfenning U, Rowe G, Van Dijk H, Van der Lans IA, Frewer LJ. Consumer evaluations of food risk management quality in Europe. Risk Analysis, 2007; 27 (6):1565-1580. 11. Tse ACB. Factors affecting consumer perceptions on product safety. European Journal of Marketing, 1999; 33 (9/10):911-925. 12. Brody AS, Frush DP, Huda W, Brent RL. Radiation risk to children from computed tomography. Pediatrics, 2007; 120 (3):677-682. 13. Feng T, Keller LR, Wang L, Wang Y. Product quality risk perceptions and decisions: Contaminated pet food and lead-painted toys. Risk Analysis, 2010; 30 (10):1572-1589. 14. Prati G, Pietrantoni L, Zani B. A social-cognitive model of pandemic influenza H1N1 risk perception and recommended behaviors in Italy. Risk Analysis, 2011; 31 (4):645-656. 15. Hong S, Collins A. Societal responses to familiar versus unfamiliar risk: Comparisons of influenza and SARS in Korea. Risk Analysis, 2006; 26 (5):1247-1257. 16. Seale H, McLaws ML, Heywood AE, Ward KF, Lowbridge CP, Van D GJ, MacIntyre CR. The community's attitude towards swine flu and pandemic influenza. Med J Aust, 2009; 191 (5):267-269. 17. Rubin GJ, Amlôt R, Page L, Wessely S. Public perceptions, anxiety, and behaviour change in relation to the swine flu outbreak: Cross sectional telephone survey. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 2009; 339. 18. Poortinga W, Bickerstaff K, Langford I, Niewöhner J, Pidgeon N. The British 2001 foot and mouth crisis: A comparative study of public risk perceptions, trust and beliefs about government policy in two communities. Journal of Risk Research, 2004; 7 (1):73-90. 23 Risk Perceptions and Behavioral Responses 19. Trumbo CW, McComas KA, Kannaovakun P. Cancer anxiety and the perception of risk in alarmed communities. Risk Analysis, 2007; 27 (2):337-350. 20. Trumbo CW, McComas KA, Besley JC. Individual- and community-level effects on risk perception in cancer cluster investigations. Risk Analysis, 2008; 28 (1):161-178. 21. Lindell MK, Perry RW. Household adjustment to earthquake hazard a review of research. Environment and Behavior, 2000; 32 (4):461-501. 22. Kates RW. Natural hazard in human ecological perspective: Hypotheses and models. Economic Geography, 1971; 47 (3):438-451. 23. McDaniels T, Axelrod LJ, Slovic P. Characterizing perception of ecological risk. Risk Analysis, 2006; 15 (5):575-588. 24. Paton D. Risk communication and natural hazard mitigation: How trust influences its effectiveness. International Journal of Global Environmental Issues, 2008; 8 (1):2-16. 25. Ray WA, Griffin MR, Schaffner W, Baugh DK. Psychotropic drug use and the risk of hip fracture. The New England Journal of Medicine, 1987. 26. Choonara I, Conroy S. Unlicensed and off-label drug use in children: Implications for safety. Drug Safety, 2002; 25 (1):1-5. 27. Aronson JK, Ferner RE. Clarification of terminology in drug safety. Drug Safety, 2005; 28 (10):851-870. 28. Leape LL, Woods DD, Hatlie MJ, Kizer KW, Schroeder SA, Lundberg GD. Promoting patient safety by preventing medical error. JAMA: the Journal of the American Medical Association, 1998; 280 (16):1444-1447. 29. Rogers RD, Robbins TW. Investigating the neurocognitive deficits associated with chronic drug misuse. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 2001; 11 (2):250-257. 30. Vincent C, Taylor-Adams S, Stanhope N. Framework for analysing risk and safety in clinical medicine. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 1998; 316 (7138):1154-1157. 31. Rothschild JM, Landrigan CP, Cronin JW, Kaushal R, Lockley SW, Burdick E, Stone PH, Lilly CM, Katz JT, Czeisler CA. The critical care safety study: The incidence and nature of adverse events and serious medical errors in intensive care. Critical Care Medicine, 2005; 33 (8):1694-1700. 32. Edwards IR, Aronson JK. Adverse drug reactions: Definitions, diagnosis, and management. The Lancet, 2000; 356 (9237):1255-1259. 33. Smith CC, Bennett PM, Pearce HM, Harrison PI, Reynolds DJM, Aronson JK, Grahame-Smith DG. Adverse drug reactions in a hospital general medical unit meriting notification to the committee on safety of medicines. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 1996; 42 (4):423-429. 34. Bate A, Lindquist M, Edwards IR, Olsson S, Orre R, Lansner A, De Freitas RM. A Bayesian neural network method for adverse drug reaction signal generation. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 1998; 54 (4):315-321. 35. Tanaka Y. Major psychological factors affecting acceptance of gene-recombination technology. Risk Analysis, 2004; 24 (6):1575-1583. 36. Siegrist M. A causal model explaining the perception and acceptance of gene technology. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 1999; 29 (10):2093-2106. 24 Risk Perceptions and Behavioral Responses 37. Allum N. An empirical test of competing theories of hazard-related trust: The case of GM food. Risk Analysis, 2007; 27 (4):935-946. 38. Peters RG, Covello VT, McCallum DB. The determinants of trust and credibility in environmental risk communication: An empirical study. Risk Analysis, 1997; 17 (1):43-54. 39. Frewer LJ, Howard C, Hedderley D, Shepherd R. What determines trust in information about food-related risks? Underlying psychological constructs. Risk Analysis, 1996; 16 (4):473-486. 40. Johnson BB, Slovic P. Presenting uncertainty in health risk assessment: Initial studies of its effects on risk perception and trust. Risk Analysis, 1995; 15 (4):485-494. 41. Viklund MJ. Trust and risk perception in western europe: A cross-national study. Risk Analysis, 2003; 23 (4):727-738. 42. Poortinga W, Pidgeon NF. Trust in risk regulation: Cause or consequence of the acceptability of GM food? Risk Analysis, 2005; 25 (1):199-209. 43. Mayer RC, Davis JH, Schoorman FD. An integrative model of organizational trust. Academy of Management Review, 1995:709-734. 44. Slovic P. Perceived risk, trust, and democracy. Risk Analysis, 1993; 13 (6):675-682. 45. Freudenburg WR. Risk and recreancy: Weber, the division of labor, and the rationality of risk perceptions. Social Forces, 1993; 71 (4):909-932. 46. Siegrist M. The influence of trust and perceptions of risks and benefits on the acceptance of gene technology. Risk Analysis, 2000; 20 (2):195-204. 47. Fidler DP. Germs, governance, and global public health in the wake of SARS. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 2004; 113 (6):799-813. 48. Thornton PM. Crisis and governance: SARS and the resilience of the Chinese body politic. The China Journal, 2009:23-48. 49. Chan LH, Chen L, Xu J. China's engagement with global health diplomacy: Was SARS a watershed? PLoS Medicine, 2010; 7 (4):e1000266. 50. Schweitzer ME, Hershey JC, Bradlow ET. Promises and lies: Restoring violated trust. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 2006; 101 (1):1-19. 51. Lewicki RJ, Wiethoff C. Trust, trust development, and trust repair. The Handbook of Conflict Resolution: Theory and Practice, 2000:86-107. 52. Dirks KT, Kim PH, Ferrin DL, Cooper CD. Understanding the effects of substantive responses on trust following a transgression. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 2011; 114 (2):87-103. 53. Haselhuhn MP, Schweitzer ME, Wood AM. How implicit beliefs influence trust recovery. Psychological Science, 2010; 21 (5):645-648. 54. Huang Y. Comparing the H1N1 crises and responses in the US and China. NTS Working Paper Series, Nanyang Technological University, 2010. 55. Kobbeltved T, Brun W, Johnsen BH, Eid J. Risk as feelings or risk and feelings? A cross-lagged panel analysis. Journal of Risk Research, 2005; 8 (5):417-437. 56. Sjöberg L. Worry and risk perception. Risk Analysis, 1998; 18 (1):85-93. 25 Risk Perceptions and Behavioral Responses 57. Batra R, Stayman DM. The role of mood in advertising effectiveness. Journal of Consumer Research, 1990:203-214. 58. Jepson C, Chaiken S. Chronic issue-specific fear inhibits systematic processing of persuasive communications. Journal of Social Behavior & Personality; Journal of Social Behavior & Personality, 1990. 59. Ter Huurne E, Gutteling J. Information needs and risk perception as predictors of risk information seeking. Journal of Risk Research, 2008; 11 (7):847-862. 60. Griffin RJ, Dunwoody S, Neuwirth K. Proposed model of the relationship of risk information seeking and processing to the development of preventive behaviors. Environmental Research, 1999; 80 (2):230-245. 61. Atkin C. Instrumental utilities and information seeking. In: Clarke P, editor. New models for mass communication research. Oxford, England: Sage; 1973. 62. Berger CR, Calabrese RJ. Some explorations in initial interaction and beyond: Toward a developmental theory of interpersonal communication. Human Communication Research, 2006; 1 (2):99-112. 63. Eagly AH, Chaiken S. The psychology of attitudes. Fort Worth: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers; 1993. 64. Ajzen I. Attitudes, personality, and behavior: 2nd ed. New York: Open University Press; 2005. 65. Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Understanding attitudes and predicting social behaviour. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc.; 1980. 66. Ajzen I, Timko C. Correspondence between health attitudes and behavior. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 1986; 7 (4):259-276. 67. Neuwirth K, Dunwoody S, Griffin RJ. Protection motivation and risk communication. Risk Analysis, 2000; 20 (5):721-734. 68. Witte K, Allen M. A meta-analysis of fear appeals: Implications for effective public health campaigns. Health Education & Behavior, 2000; 27 (5):591-615. 69. Hammitt JK. Risk perceptions and food choice: An exploratory analysis of organic-versus conventional-produce buyers. Risk Analysis, 1990; 10 (3):367-374. 70. Brewer NT, Chapman GB, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, McCaul KD, Weinstein ND. Meta-analysis of the relationship between risk perception and health behavior: The example of vaccination. Health Psychology, 2007; 26 (2):136-145. 71. Gordon J. Risk communication and foodborne illness: Message sponsorship and attempts to stimulate perceptions of risk. Risk Analysis, 2003; 23 (6):1287-1296. 72. Vernon SW. Risk perception and risk communication for cancer screening behaviors: A review. JNCI Monographs, 1999; 1999 (25):101-119. 73. Brewer NT, Weinstein ND, Cuite CL, Herrington JE. Risk perceptions and their relation to risk behavior. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 2004; 27 (2):125-130. 74. Kleinhesselink RR, Rosa EA. Cognitive representation of risk perceptions a comparison of Japan and the United States. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1991; 22 (1):11-28. 75. Holtgrave DR, Weber EU. Dimensions of risk perception for financial and health risks. Risk Analysis, 2006; 13 (5):553-558. 26 Risk Perceptions and Behavioral Responses 76. Karpowicz-Lazreg C, Mullet E. Societal risk as seen by the French public. Risk Analysis, 2006; 13 (3):253-258. 77. Anderson JC, Gerbing DW. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 1988; 103 (3):411-423. 78. Kim HW, Xu Y, Koh J. A comparison of online trust building factors between potential customers and repeat customers. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 2004; 5 (10):392-420. 79. Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH, Berge JMF. Psychometric theory. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1967. 80. Fornell C, Larcker DF. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 1981:382-388. 81. Hair Jr JF, Anderson RE, Tatham RL, Black WC. Multivariate Data Analysis. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company; 1992. 82. Gerbing DW, Anderson JC. An updated paradigm for scale development incorporating unidimensionality and its assessment. Journal of Marketing Research, 1988:186-192. 83. Hoyle RH, Panter A. Writing about structural equation models. In R. H. Hoyle (ed.), Structural equation modeling (pp. 158- 176): Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1995. 84. Lee K. How the Hong Kong government lost the public trust in SARS: Insights for government communication in a health crisis. Public Relations Review, 2009; 35 (1):74-76. 85. CNN-News. Who targets SARS "super http://edition.cnn.com/2003/HEALTH/04/05/sars.vaccine/index.html, 2003. spreaders". 86. Lee JE, Lemyre L. A social‐cognitive perspective of terrorism risk perception and individual response in Canada. Risk Analysis, 2009; 29 (9):1265-1280. 87. China-Daily-BBS. Chinese consumers DIY medicine wraps to avoid potential toxic gelatin. http://bbs.chinadaily.com.cn/thread-744026-1-1.html, 2012. 88. Krystallis DA, Frewer L, Rowe G, Houghton J, Kehagia O, Perrea T. A perceptual divide? Consumer and expert attitudes to food risk management in Europe. Health, Risk & Society, 2007; 9 (4):407-424. 89. Committee on Ranking FDA Product Categories Based on Health Consequences, A risk-characterization framework for decision-making at the Food and Drug Administration, 2011, National Research Council, http://dels.nas.edu/Report/Risk-Characterization-Framework-Decision/13156. 90. Siegrist M, Earle TC, Gutscher H. Test of a trust and confidence model in the applied context of electromagnetic field (EMF) risks. Risk Analysis, 2003; 23 (4):705-716. 91. Earle T, Siegrist M, Gutscher H. Trust and confidence: A dual-mode model of cooperation. Unpublished manuscript, Western Washington University, WA, USA, 2002. 92. Barber B. The logic and limits of trust. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 1983. 93. Barber B. Trust in science. Minerva, 1987; 25 (1):123-134. 94. Rogers RW. A protection motivation theory of fear appeals and attitude change. The Journal of Psychology, 1975; 91 (1):93-114. 27 Risk Perceptions and Behavioral Responses Appendix Trust in the State FDA Perceived Efficacy of Countermeasures Risk Perception Risk Avoidance Trust in the Pharmaceutical Companies Concern Information Seeking Trust in the Pharmaceutical Capsule Producers Need for Information Fig. 1. Hypothesized model of risk perceptions and behavioral responses in the toxic drug capsule crisis 28 Risk Perceptions and Behavioral Responses Table I. Descriptive Statistics and Intercorrelations of the Constructs M S.D. 1 2 3 1. Risk perception 5.58 1.24 2. Concern 5.81 1.23 0.69*** 3. Risk avoidance 4.91 1.50 0.49*** 0.44*** 4 4. Trust in the pharmaceutical 3.76 1.18 capsule producers -0.01 -0.16 -0.06 5. Trust in the pharmaceutical 3.00 1.32 companies 0.03 -0.09 0.01 0.47*** 5 6 6. Trust in the State FDA 2.82 1.21 -0.15* -0.16* 0.05 0.52*** 0.54*** 7. Perceived efficacy of the countermeasures 3.49 1.33 -0.02 -0.08 0.10 0.47*** 0.43*** 0.66*** 8. Information seeking 4.37 1.31 0.24** 0.33*** 0.43*** 0.08 9. Need for information 4.12 1.69 0.04 0.01 0.10 Note: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. 29 0.11 0.19* 7 8 0.34*** 0.47*** 0.43*** 0.39*** 0.62*** 0.39*** 9 Risk Perceptions and Behavioral Responses Table II. Factor Loading Estimates for Indicator Variables Factor loading Factors/Variables F1 Risk perception V1 V2 V3 V4 Toxic capsules have adverse effects on human health. The harmful ingredients that toxic capsules contain affect curative effects of the drugs. The harmful ingredients that toxic capsules contain cause permanent damage to human health. The harmful ingredients that toxic capsules contain increase the chance of having other diseases. The harmful ingredients that toxic capsules contain cause damage to some organs of human V5 body. F2 Toxic capsules are produced by only a small percentage of capsule producers, and most capsule producers are trustable. V2 Those capsule drugs that are not released by the State FDA online are safe and reliable. V3 Most capsules in the market are safe and reliable. V1 The pharmaceutical companies are innocent. Purchasing toxic capsules is the individual behavior of the employees in the procurement department of the companies. The relevant pharmaceutical companies are innocent. They purchased toxic capsules from V2 capsule producers without knowing they are toxic. V1 V2 V3 V4 0.92 0.91 0.78 0.74 0.82 0.68 0.69 0.70 0.75 0.85 Trust in the pharmaceutical companies V1 F6 0.87 Risk avoidance V1 I try to avoid the consumption of capsule drugs unless I have to. I will not purchase any capsule drugs and use non-capsule drugs instead if necessary in the V2 coming a few months. V3 When taking capsule drugs, I will open the capsule and consume the ingredients inside capsules. Before taking capsule drugs, I will check the product batch number with excessive levels of V4 chromium released by the State FDA online and decide whether to consume them. F4 Trust in the pharmaceutical capsule producers F5 0.87 Concern V1 If I have taken capsule drugs recently, I will feel worried about my health. If I have taken drugs related to toxic capsules recently, I will feel afraid that the harmful V2 ingredients the toxic capsules contain affect my health. V3 If my family or friends have taken capsule drugs recently, I will feel worried about their health. If a pregnant woman who I know has taken capsule drugs recently, I will feel worried about the V4 health of her baby. F3 0.83 0.75 0.76 0.85 0.85 0.91 Trust in the State FDA The regulation rules of drug safety are well developed in China. The regulation and supervision of drug safety is sufficient. The drug quality inspection technique is reliable. The State FDA of China is well prepared for any drug safety problems. 0.90 0.92 0.85 0.91 F7 Perceived efficacy of the countermeasures V1 The Chinese government and corresponding agencies have dealt with the toxic capsule crisis promptly and effectively. 30 0.86 Risk Perceptions and Behavioral Responses V2 The recall of toxic capsule drugs is reliable and timely. The countermeasures dealing with the toxic capsule crisis can prevent the outbreak of similar V3 crises. F8 0.80 Information seeking After the outbreak of the toxic capsule crisis, I searched for detailed information about the crisis immediately. When it comes to drug safety, I will search for the latest news about the regulation and V2 supervision of drug safety. Before taking capsule drugs, I will search for relevant information to decide whether they are V3 safe for use. V1 F9 0.85 0.76 0.96 0.81 Need for information V1 The public media reported the toxic capsule scandal promptly. V2 The reports of the toxic capsule scandal by the public media are objective and reliable. The product batch number with excessive levels of chromium reported by the public media is V3 sufficient. V4 I can conveniently get the information on the toxic capsule scandal which I need. 31 0.68 0.80 0.82 0.73 Risk Perceptions and Behavioral Responses Table III. Test Statistics for Hypothesized Model Model χ2 df CFI Initial 693.20 452 0.97 Addition of two significant paths a 675.07 450 0.97 Δχ2 Δdf 18.13 2 Note. CFI = comparative fit index. Trust in the pharmaceutical companies trust in the State FDA, trust in the pharmaceutical capsule producers trust in the State FDA. a 32 Risk Perceptions and Behavioral Responses (R2=0.037) Trust in the State FDA 0.46*** Perceived Efficacy of Countermeasures -0.24** (R2=0.51) 0.50*** Trust in the Pharmaceutical Companies (R2=0.35) 0.42*** 0.26*** 0.47*** Risk Perception N.S. 0.70*** 0.16* N.S. Risk Avoidance 0.34*** Concern 0.34*** (R2=0.22) Information Seeking 2 (R =0.48) 0.40*** Trust in the Pharmaceutical Capsule Producers Need for Information (R2=0.27) (R2=0.25) Note: *: p < 0.05, t > 1.96; **: p < 0 .01, t > 2.58; ***: p 0.001, t > 3.29. Fig. 2. Results of the testing of the conceptual model (Chi-square = 675.07, d.f. = 450, p = 0.000, RMSEA = 0.052) 33