Rob McLennan. ENGL218 Essay, due 1 October 2010 Wooing Us

advertisement

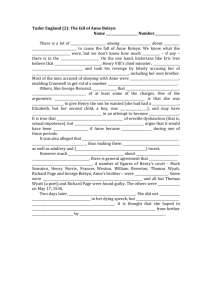

Wooing Us by Wooing Anne: A Cinematic History of Shakespeare’s Richard III By Rob McLennan Due: 1 October, 2010 Rob McLennan. ENGL218 Essay, due 1 October 2010 Any production of a Shakespearean play, be it theatrical or cinematic, allows us the opportunity to view Shakespeare’s original play in a fresh context. Directors, actors and producers of such productions ‘borrow’ from the original text in ways they hope will resonate with a contemporary audience and ‘keep Shakespeare relevant’. Shakespeare’s Richard III, is particularly challenging in that Richard’s wooing of Anne Neville in the second scene, relies extensively on Anne — and the audience — suspending their “moral judgment and historical memory”. In a single scene, we are expected to believe that a recently widowed young woman will submit to the sexual advances of the very man who has only recently killed her husband and father-in-law. This pivotal scene is crucial in establishing the audience’s understanding of Richard as a powerfully manipulative man. But, just as important in this scene is the audience’s acceptance of Anne’s capitulation. A challenge all productions must face is how to encourage viewers to “abandon disbelief” at this early point in the play. If we ‘buy’ this scene, the rest of the play becomes easier to enjoy. I will demonstrate that the credibility of ‘the Anne scene’ is just as important in modern cinematic productions of the play as it was in Shakespeare’s time. In chronological order, I will discuss treatments of the scene by the British Co-operative Film Company’s Richard III (1911), M. B. Dudley’s The Life and Death of Richard the III (1912), Laurence Olivier’s Richard III (1955), Richard Loncraine’s Richard III (1995), and Al Pacino’s Looking for Richard (1996). In particular, I will look at how the films’ directors and actors have creatively used cameras, sensuality, motion and the source script to make Anne’s vulnerability seem ‘real’, and thus her submission seem plausible. In Shakespeare’s original text, the strength of conviction in “Richard’s perverse wooing of Anne over the coffin”, as Phyllis Rackin describes it, (Shakespeare 345) lies in the extensive repartee between Richard and Anne. Over a 2 Rob McLennan. ENGL218 Essay, due 1 October 2010 prolonged period of time, Anne’s resolve is eventually eroded as Richard repeatedly and incisively rebuts her every curse. Richard’s power here is in his ‘way with words’. This suited the convention of the Shakespeare’s time; text was ‘king’ when it came to describing the action. But the invention of the camera, three centuries later, has helped make this scene credible in ways Shakespeare could not have imagined. In a 1911 silent movie version of Richard III by the British Co-operative Film Company, the inability to record and synchronise voice with picture was subverted with an impressionistic, “pictorial style of acting” preferred by its lead actor, Frank Benson (Burrows 83). In the scene in which Richard woos Anne, positioned somewhat later in the sequence than in Shakespeare’s play, Richard’s hypnotic power over Anne is represented with balletic and graceful movement as “Richard holds his hand over hers and — without physical contact — guides it upwards like a snake charmer, so that he can place a ring upon it as she stands in a passive trance”. Benson’s “constant, vigorous performative movement” was captured with a fixed camera using “extreme long-shot framing” (Burrows 88). Additionally, the extra wide image, which affords the actors a wide “playing area”, is used to good effect in representing Anne’s conflicted inner world during the scene. With “alternating hostility and submission … she moves from” side to side of the screen. Anne’s conflicted state of mind is clear as she simultaneously averts her eyes while reluctantly offering Richard her hand so he can place a ring on her finger. However, a silent movie released one year later, on the other side of the Atlantic, The Life and Death of Richard III, was let down by the “performance” of its lead actor (Loehlin 182). Warde’s Victorian style does not translate well to screen as does Benson’s “pantomimic” style (Burrows 86), and as such, his performance is perhaps less successful in ‘winning us over’. Where Benson’s “ferocity and vigour” 3 Rob McLennan. ENGL218 Essay, due 1 October 2010 are favourably embellished by the use of long-distance, fixed camera shots, the mostly “middle distance” camera shots of Warde’s film reveal too much detail in the actor’s overly animated, “nineteenth-century” style: “every stagey flourish of gesture or expression is seen too close, so that Warde seems to be playing to the galleries far behind the viewer”. The crucial connection between audience and actor seems lost. Warde’s “hearty slap of the thigh” upon his Richard winning Anne at the scene’s end, in particular, comes across as quaint and farcical (Loehlin 183). In his 1955 movie version of Richard III, actor and director, Laurence Olivier makes the seduction of Anne more plausible by spreading the action over two scenes. The onus on the audience to suspend belief is not taken lightly. Olivier believed that if the scene was “too sudden on the screen the unaccustomed [popular] audience would not be persuaded” (Hindle 155). By splitting the scene, and cleverly rearranging Shakespeare’s text, Olivier affords Richard twice the opportunity to boast to us (via one of many direct addresses to the camera) about his prowess: “I’ll have her, but I will not keep her long” (Shakespeare 1.2.249); followed later with “Was ever woman in this humour woo’d? / Was ever woman in this humour won?”(1.2.24748) Additionally, by splitting the Anne scene in two, Olivier gives his camera operators twice the opportunity to capture Anne’s reactions and facial expressions, which do the work of many words. Claire Bloom excellently portrays Anne’s dual emotions with conflicted expressions at the end of each of the sub-scenes. As she exits the first of these, a close up of her face reveals that the ‘seed’ of Richard’s lewd proposal has been planted, both for her and for the audience. Only moments after spitting in Richard’s face, Anne’s expression, although a firm gaze, has softened appreciably. We see her face in close-up as she departs, and witness her looking back 4 Rob McLennan. ENGL218 Essay, due 1 October 2010 at Richard in the corner of her eye with an expression that now seems infused with a sensual curiosity. In Olivier’s interruption of the original scene, Richard turns his attention to the pressing matter of Clarence’s disposal, allowing Anne — and the audience — extra time to digest Richard’s outrageous proposition. At the end of the second ‘half’ of the scene, Anne almost falls into a kiss with Richard while calling him “fouler toad”. Bloom’s Anne again perfectly expresses a mixture of self-loathing and desire as the power of Richard’s beguiling seduction takes hold. Anne’s arousal is matched by her inner sense of revulsion. Olivier’s expansion of the encounter with Anne also enables him to double Anne’s reaction of spitting into Richard’s face. When the “your bedchamber” ‘bomb’ has been dropped into the conversation (Shakespeare 1.2.119), Anne reacts by spitting in his face, a response repeated in the second ‘half’ of the scene. However, this reaction by Anne only occurs once in Shakespeare’s original stage directions. By making Anne spit on two separate occasions, Olivier provides necessary contrast to her escalating attraction to Richard. Olivier effectively adds credibility, allowing the viewer to see Anne as a fragile woman in ‘two minds’. Although the 1995 Loncraine film is set in a semi-fictitious, 1930s context, his Anne is vulnerable for similar reasons to Olivier’s — and, indeed, Shakespeare’s. Richard (Ian McKellen) preys on her vulnerability in the wooing scene by identifying her desire to maintain the lifestyle to which she has become accustomed. He capitalises on this moment when “Lady Anne’s emotional juices are in full flood, as her grief and anger turn to curiosity and the need to be involved with the world once more”. McKellen notes that Richard picks up on the fact that “Lady Anne's particular happiness lies not just in love but in being married to the late heir-to-the-throne, with the promise of influence and riches as his consort … that a liaison with Richard would 5 Rob McLennan. ENGL218 Essay, due 1 October 2010 lead her back to those privileges (Rodes 115). Michael Anderegg expands on this: “On the losing side of a civil war, Anne is smart enough to know where her creature comforts lie” (140). The Loncraine film also makes the Anne scene convincing by exploiting the “sexual innuendo” in Shakespeare’s play at “this moment of first encounter” (Rodes 115). David Rodes defines the scene as an “exchange of bodily fluids” (115). Adhering to the stage directions in the original play, Anne spits in Richard’s face. In return, McKellen’s Richard slithers a ring, “wet with [his own] saliva, onto her engagement finger” (qtd. in Rodes 116). Needless to say, McKellen involves the ring in ways which would probably not have been appropriate in Shakespeare’s time. As he nonchalantly utters the words, “your bedchamber”, McKellen actually slips momentarily (as he does at numerous times in the film) into camera-wooing mode, inviting us — the viewers — into a world he shares exclusively with us. He then, just as deftly, shifts his attention back to Anne: “To leave this keen’d encounter of our wits / Your beauty which did haunt me in my sleep …” (Shakespeare 1.2.124/131). McKellen’s treatment of this “turn of conversation that is among the most psychiatrically daring and elliptical in all Shakespeare” (Rodes 115), differs from Olivier’s. Where the latter speaks the words directly into Anne’s ear, the former slips deliberately into the “fourth wall” dimension (Jorgens 143), addressing his plan exclusively to us. This is a consistent point of comparison: in his engaging with the audience, Olivier takes a more traditional, Shakespearean approach, delighting in sharing his conquests with us at the end of the scene(s), in Anne’s absence; McKellen, on the other hand, rather inventively flaunts his masterful achievements ‘on the fly’, regardless of who else happens to be in his vicinity. Anne, it would seem, is oblivious to the words, “Your bedchamber”, although it could be argued that Richard is not 6 Rob McLennan. ENGL218 Essay, due 1 October 2010 concerned about whether she overhears him or not; that he is, in fact, hoping to ‘plant the seed’ of a potential sexual liaison in a more subliminal way than does Olivier. Looking for Richard, a 1996 film project initiated by Al Pacino, takes a similar approach in focusing on Anne’s vulnerability. In a performance Cartelli and Rowe describe as “unusually erotic” (102), Pacino attempts to make the wooing of Anne persuasive by investigating the underlying motivation of Anne’s capitulation. He specifically requests a young actress (Winona Ryder) so that we can believe at least part of her vulnerability is accountable to youth. But he also draws attention to the fact that Anne “has no sponsor or protector in the royal court” (Cartelli and Rowe 101). This is useful advice that helps both the actors and the viewers to understand why Anne would relent the way she does in Act 1, Scene 2 of Shakespeare’s play. Cameras are used to great effect in Pacino’s enactments. “Tight, circling camera close-ups” heighten the dramatic action. By prioritising “gesture over word”, Pacino demonstrates an acting style favoured by American actors. His fluid movements and physical gestures distantly echo the intentions of Frank Benson more than 80 years prior. And, like Olivier and McKellen, Pacino takes liberties with the original text, in order to ‘cut to the chase’ of highlighted moments in the play. Pacino is very persuasive, for example, at the end of the Anne scene, where it is “both shocking and exhilarating to witness how … [he] reduces an actor’s dream of a 36line speech to three lines”: “I’ll have her, but I will not keep her long”. Pacino lets his actions paraphrase the text, accompanying this line with a “gleefully triumphant laughter” and “the swinging of his riding crop”. At other times the cameras augment close encounters between the actors, allowing a greater level of “intimacy the stage does not usually afford” (Cartelli and Rowe 102). In Pacino’s docudrama, Peter Brook asserts that “very few stage actors can project without losing a degree of ‘truth’ 7 Rob McLennan. ENGL218 Essay, due 1 October 2010 whereas film actors can vary volume of speech for greater intimacy.” This greater level of intimacy “allow[s] the verse to be a man speaking his inner world” (Cartelli and Rowe 99). In Looking for Richard, fluid camera motion and close-ups aid Pacino’s crusade in finding the “truth” in Shakespeare’s Richard III, and help the audience “to abandon disbelief” (Cartelli and Rowe 102). By comparing five cinematic productions of the play in the twentieth century, I have demonstrated some contrasting approaches that film directors and actors of the twentieth century have taken in making Richard’s wooing of Anne seem convincing. In my view, all but one — the 1912 film — succeed. And they do so through innovative use of the camera, inventive treatment of Shakespeare’s original text, and some shrewd acting choices. 8 Rob McLennan. ENGL218 Essay, due 1 October 2010 Works Cited Anderegg, Michael. Cinematic Shakespeare. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield, c2004. Print. Cartelli, Thomas, and Katherine Rowe. New Wave Shakespeare on Screen. Cambridge, UK : Polity Press, 2007. Print. Jorgens, Jack J. “Laurence Olivier’s Richard III.” Shakespeare on Film. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, c1977. 136-147. Print. Hatchuel, Sarah. Shakespeare : from stage to screen. Cambridge, UK ; New York : Cambridge University Press, 2004. 78-93. Print Hindle, Maurice. Studying Shakespeare on Film. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire; New York: Palgrave Macmillan, c2007. Print. Howlett, Kathy M. Framing Shakespeare on film. Athens: Ohio UP, 2000. Print. Loehlin, James N. “‘Top of the World, Ma’: Richard III and Cinematic Convention.” Shakespeare, the movie II: popularizing the plays on film, TV, video, and DVD. Ed. Richard Burt and Lynda E. Boose. London ; New York, N.Y. : Routledge, 2003. 173-185. Print. Rodes, David. “Teaching Shakespeare with Examples from Film.” Pacific Coast Philology. 33.2 (1998): 112-117. JSTOR. Web. 29 Aug. 2010. Shakespeare, William. Richard III. Ed. Barbara A. Mowat and Paul Werstine. New York: Washington Square P, 1996. Print. 9