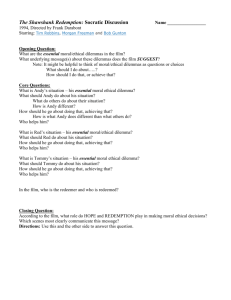

Dissertation (Outline of Proposal)

advertisement