History 101: Historical Studies: Theories and Practices

advertisement

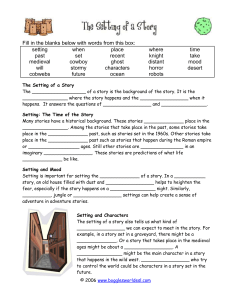

History 101: Historical Studies: Theories and Practices Workshop: Ritual and Community in the Middle Ages V57.0101 Department of History New York University Spring 2011 ____________________________________________________________________________________ Instructor: email: Office Location: Office Hours: Class Time: Class Location: LECTURE Professor Edward Berenson edward.berenson@nyu.edu 15 Washington Mews TBA T 11-12:15 TBA WORKSHOP Michael Peixoto mjp346@nyu.edu 506 KJCC T 2-4 W 11-1:30 TBA COURSE DESCRIPTION This course is designed for students intending to major in history. It is organized around a lecture component, common to all students who enroll in the course, and a workshop that is chronologically and regionally specific. Both lecture and workshop share the common goal of introducing students to the work of the historian and will cover topics including the historical development of professional history, professional ethics, objectivity and hermeneutics, and the nature of historiography. The course will be structured around detailed reading and discussion of primary and secondary sources, as well as various exercises in research and writing. Through this course, students will learn how to find and analyze primary sources, how to develop a research topic, and how to critically examine secondary literature. Although the readings assigned for lectures will be discussed, primarily the workshop will be concerned with the study of the social and cultural history of medieval Europe. The performance of ritual was an essential element of medieval life. Everyone from peasants to popes participated constantly in ritualized activity. Maintaining particular rituals allowed medieval institutions to gain power, exert social control, and build communities. In the same way, the alterations of these same activities could defame, isolate, and cause social havoc. This class takes a historical approach to the rituals used by both medieval secular and religious institutions aiming to understand what medieval rituals were, how they served to create power for institutions and particular social groups, and how they could be manipulated to negotiate status and control. Simultaneous to each of the assigned readings on rituals and community, this class will examine the historian's role in uncovering and writing about medieval historical sources. The aim of the class is to provide students with an understanding of how the medieval history is written, what sorts of intellectual tools they as scholars would need to pursue medieval history at a high level, and how, using these tools, medieval historians can find common threads that link many aspects of medieval society together, such as ritual and community. The goal of this workshop is to prepare students for research in history. To this end, students will be expected to confront a variety of primary sources, to absorb and critique secondary literature, and to master the empirical skills necessary for developing a viable research project. REQUIREMENTS Students will be expected to come to class each week prepared to discuss the assigned reading (with hardcopies of the reading in-hand). Active participation in discussion will form a substantial part of your final grade. Students will also hand in four short response papers (2 pages each) analyzing the workshop reading for that week and one short archival analysis paper (2 pages). There will be eight opportunities to hand in these papers. No response papers will be accepted on reading that has already been discussed in 1 class. Students will turn in two short papers analyzing primary sources, a 3 page paper analyzing a single source and 6 page paper analyzing several sources. Finally, students will produce a research proposal of about 7-10 pages that proposes a viable research project grounded in a specific body of sources and developing a question based on existing scholarly literature. There will also be a mid-term and a final exam based wholly upon material from the lecture portion of the class. GRADING Participation: 30% Document Exercises: 15% Mid-term: 15% Final Exam: 20% Research Proposal: 20% READING Most of the reading will be available on Blackboard, but it is essential that you bring hardcopies to each class. Unless there is a medical reason, I do not allow laptops or other electronic devices in class. REQUIRED TEXTS Feudal Society in Medieval France: Documents from the County of Champagne, ed. Theodore Evergates Suger of St Denis, The Deeds of Louis the Fat, trans. John Moorhead and Richard C. Cusimano (Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 1992). Jean-Claude Schmidtt, The Holy Greyhound: Guinefort, Healer of Children since the Thirteenth Century (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009). Thomas N. Bisson, Cultures of Power: Lordship, Status, and Process in Twelfth-Century Europe (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1995). Optional but recommended for students who have not taken a medieval history course before: Barbara H. Rosenwein, A Short History of the Middle Ages, Volume II: From c.900 to c.1500, 3rd Edition (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2009). SHEDULE OF READINGS Week 1 Lecture (Jan.25): Introduction to the course Workshop (Jan.26): Introduction to the Processes of Medieval History - The Auxiliary Sciences Optional Reading for Background: Rosenwein, Short History, pp.TBA Week 2 Lecture (Feb.1): History: Interpretation and Imagination *Reading: Natalie Zemon Davis, The Return of Martin Guerre Film: The Return of Martin Guerre Interview with N.Z. Davis Workshop (Feb.2): Defining Medieval Society, A Historical Problem Georges Duby, The Three Orders: Feudal Society Imagined, trans. Arthur Goldhammer (Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1980), pp.123-166. Optional Reading for Background: Rosenwein, Short History, pp.TBA. Assignment: Library Exercise Due (typed responses to attached handout) Week 3 Lecture (Feb.8): NZ Davis and her Critics: Historians Debate Martin Guerre Articles from the American Historical Review. 2 Workshop (Feb.9): Binding the Community 1 - The Ritual of Vassalage Primary Source: Feudal Society in Medieval France, pp.1-18; 74-82. Theodore Evergates, "Nobles and Knights in Twelfth-Century France," in Cultures of Power, pp.11-35. Dominique Barthélemy, "Castles, Barons, and Vavassors in the Vendômois and Neighboring Regions in the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries," in Cultures of Power, pp.56-68. Optional Reading for Background: Rosenwein, Short History, pp.TBA Assignment: First Response Paper Opportunity (2 pages) Week 4 Lecture (Feb.15): What Historians Do *John Lewis Gaddis, The Landscape of History Workshop (Feb.16): Binding the Community 2 - The Ritual of Kingship Primary Source: Suger of St Denis, The Deeds of Louis the Fat, pp.21-TBA Philippe Buc, "Principes gentium dominantur eorum: Princely Power Between Legitimacy and Illegitimacy in Twelfth-Century Exegesis," in Cultures of Power, pp.310-328. Geoffrey Koziol, "England, France, and the Problem of Sacrality in Twelfth-Century Ritual," in Cultures of Power, pp.124-148. Optional Reading for Background: Rosenwein, Short History, pp.TBA Assignment: Second Response Paper Opportunity (2 pages) Week 5 Lecture (Feb.22): What Not to Do David H. Fischer, Historians’ Fallacies Margaret MacMillan, Dangerous Games. The Uses and Abuses of History Ron Robin, Scandals and Scoundrels Workshop (Feb.23): Binding the Community 3 - Episcopal Investiture Primary Source: Medieval Sourcebook Documents on the Investiture Controversy [Blackboard] Maureen Miller, "Urban Space, Sacred Topography, and Ritual Meanings in Florence: the Route of the Bishop's Entry, c.1200-1600," in The Bishop Reformed: Studies of Episcopal Power and Culture in the Central Middle Ages, ed. J. Ott and A. T. Jones (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007), pp.237-249. Optional Reading for Background: Rosenwein, Short History, pp.TBA Assignment: Single Source Analysis Paper (3 pages) Week 6 Lecture (March 1): Historians' Debate: The Origins of World War I Fritz Fischer, AJP Taylor Selected Primary Source Documents Workshop (March 2): The Authority the Written Word Primary Source: Medieval Sourcebook, "The Donation of Constantine, c.750-800" online at http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/donatconst.html Constance B. Bouchard, "Forging Papal Authority: Charters from the Monastery of Montier-enDer," Church History 69:1 (2000): 1-17. Giles Constable, “Forgery and Plagiarism in the Middle Ages,” Archiv für Diplomatic 29 (1983): 1-41. Marco Mostert, "Forgery and Trust," in Strategies of Writing: Studies on Text and Trust in the Middle Ages, ed. Petra Schulte, Marco Mostert, and Irene van Renswoude (Turnholt: Brepols, 2008), pp.37-59. 3 Assignment: Third Response Paper Opportunity (2 pages) Week 7 Lecture (March 8): Mid-Term exam Workshop (March 9): Medieval Writing Michael Clanchy, From Memory to Written Record: England, 1066-1307 (rev. ed., 1994), pp. 81113, 224-252, 294-327. Benjamin Arnold, "Instruments of Power: The Profile and Profession of ministeriales Within German Aristocratic Society (1050-1225)," in Cultures of Power, pp.36-55 *Field Trip: This class will meet at 11:30am at the Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Butler Library on the campus of Columbia University (subway stop is 116th street on the 1 train). Week 8 Lecture (March 22): Origins of the French Revolution *Georges Lefebvre, The Coming of the French Revolution Sièyes, “What is the Third Estate,” “Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen,” “Tennis Court Oath.” Workshop (March 23): The Peace of God Primary Source: Medieval Sourcebook, "Truce of God - Bishopric of Terouanne, 1063," online at http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/t-of-god.html Primary Source: Medieval Sourcebook, Letaldus of Micy, The Journey of the Body of St. Junianus to the Council of Charroux, online at http://urban.hunter.cuny.edu/~thead/charroux.htm Primary Source: "The Peace League of Bourges" as described in Andrew of Fleury, Miracles of St. Benedict, online at http://urban.hunter.cuny.edu/~thead/bourges.htm Source Reading: Galbert of Bruges, The Murder of Charles the Good (1960), pp.79-119. Thomas Head, “The Judgment of God: Andrew of Fleury’s Account of the Peace League of Bourges,” in The Peace of God: Social Violence and Religious Response in France around the Year 1000 (Ithaca; London, 1992), pp. 219-238. Assignment: Archival Source Paper Due (2 pages) & Fourth Response Paper Opportunity (2 pages) Week 9 Lecture (March 29): The French Revolution: The Classic Debate Edmund Burke, Reflections on the Revolution in France Tom Paine, The Rights of Man Workshop (March 30): The Ordeal Primary Source: Medieval Sourcebook, "Ordeal of Boiling Water, 12th or 13th Century," online at http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/water-ordeal.html Stephen White, "Proposing the Ordeal and Avoiding It: Strategy and Power in Western French Litigation, 1050-1110," in Cultures of Power, pp.89-123. Peter Brown, "Society and the Supernatural: A Medieval Change," Daedalus, 104 (1975): 13640. Robert Bartlett, Trial by Fire and Water: the Medieval Judicial Ordeal (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1986), pp.13-52. Assignment: Fifth Response Paper Opportunity (2 pages) Week 10 Lecture (April 5): Debating the Terror: Circumstances or Ideology? 4 Albert Soboul, The French Revolution Francois Furet, “The Revolutionary Catechism” R.R. Palmer, Twelve Who Ruled Maxmilien Robespierre, “The Terror” Burke on democracy and violence Workshop (April 6): Law and Judgment Primary Source: Feudal Society in Medieval France, pp. 83-95; 123-134. Stephen White, “‘Pactum…Legem Vincit et Amor Judicium’: The Settlement of Dispute by Compromise in Eleventh-Century Western France,” American Journal of Legal History 22 (1978): 281-308. Lester Little, "Anger in Monastic Curses," in Anger's Past: The Social Uses of an Emotion in the Middle Ages, ed. B. Rosenwein (1998), pp. 1-35. Assignment: Multiple Source Paper Due (5-6 pages) Week 11 Lecture (April 12): Was the Revolution Good for Women? Joan Scott, Only Paradoxes to Offer Joan Landes, Women and the Public Sphere in the Age of Democratic Revolution Lynn Hunt, The French Revolution Olympe de Gouges, “Declaration of the Rights of Women and Citizen” Workshop (April 13): Gift Giving Primary Source: Feudal Society in Medieval France, pp.49-67; 135-144. Constance B. Bouchard, Sword, Miter, and Cloister: Nobility and the Church in Burgundy, 9801198 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1987), pp.171-246. Assignment: Sixth Response Paper Opportunity (2 pages) Week 12 Lecture (April 19): Why Empire? Anthony Webster, The Debate on the Rise of the British Empire Primary sources: Seeley, Ruskin, Ferry, Prevost-Paradol, Chamberlain Workshop (April 20): Saints and Relics Jean-Claude Schmidtt, The Holy Greyhound, pp.37-123. Assignment: Seventh Response Paper Opportunity (2 pages) & Outlines for Research Proposal Due (2 pages) Week 13 Lecture (April 26): Empire and the Origins of World War I Lenin, Fritz Fischer, AJP Taylor Workshop (April 27): Remembering the Dead Primary Source: Document Packet [on Blackboard] Megan McLaughlin, "The Twelfth-Century Ritual of Death and Burial at Saint-Jean-en-Vallée in the Diocese of Chartres," Revue bénédictine 105:1-2 (1995): 155-166. Patrick J. Geary, Living with the Dead in the Middle Ages (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1994), pp.77-94; 163-193. Assignment: Eighth Response Paper Opportunity (2 pages) Week 14 Lecture (May 3): Was Empire Popular? Bernard Porter, The Absent-Minded Imperialists 5 Ronald Robinson and John Gallagher, Africa and the Victorians John M. MacKenzie, Imperialism and Popular Culture Tony Chafer and Amanda Sackur, Promoting the Colonial Idea: Propaganda and Visions of Empire in France Workshop (May 4): Polluted Rituals - Accusations of Heresy Primary Source: "The Articles of Accusation 12 August 1308" in Malcolm Barber, The Trial of the Templars (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978), pp.248-252. Primary Source: Inquisitor's Manual of Bernard Gui [d.1331], early 14th century, trans. J. H. Robinson, Readings in European History, (Boston, 1905), pp. 381-383. http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/gui-cathars.html Anne Gilmour-Bryson, "The Templar Trials: Did the System Work?" Medieval History Journal 3:1 (2000): 41-65. Jonathan Riley-Smith, "Were the Templars Guilty?" in The Medieval Crusade, ed. Susan J. Ridyard (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2004), pp.107-124. Assignment: Final Research Proposal Paper Due (7-10 pages) Final Exam Info TBA 6 Assignment: Library Exercise Due February 2 Instructions: For each of the 10 questions below, use the research guide and library resources to come to an answer. Then write a few brief sentences describing how you came to find the answer. The assignment should be typed up and handed in next week. 1) Which of these are primary and which are secondary sources? J.M. Wallace-Hadrill, The Long-Haired Kings Gregory of Tours, The History of the Franks Lewis G.M. Thorpe, Two Lives of Charlemagne Richard Sullivan, The Coronation of Charlemagne M. Gabriele and J. Stuckey, The Legend of Charlemagne John Benton, Self and Society in Medieval France 2) Describe the contents of the MGH, Epistolae 1, 1887. 3) Describe the seal of the 3 French towns of Gravelines, Meulan, and Orchies. 4) List in proper bibliographic form (Chicago Manuel Style) the articles in English on the subject of the medieval judicial ordeal written since 2004. 5) List 5 translated sources for the First Crusade available at BOBST Library. 6) Transcribe this. Hint: Adriano Cappelli is a helpful guy even if you don't read Italian! 7) List the witnesses named in the charter of a gift from 1023 in the cartulary of St.-Marcellès-Chalon? Hint: these names are usually at the end of a charter. 8) Who are the leading scholars working on the history of the Cathars in English? 9) What is 1 Florentine Florin worth in the money of Provins in Champagne in 1265? 10) Where did this image come from and where would you find it for scholarly use? (Image on Back) 7 8 Assignment: Single Source Paper Due: February 23 History is written through the careful analysis of materials, largely written, from the past. As historians, we use these documents to make arguments for both change and continuity over time and to uncover information about past people. Primary sources are the principle tool of the historian in this quest. These sources must be read for all of the information they can yield. For this reason, historians must take a "total social" approach to their reading of documents. I this assignment, in consultation with the workshop instructor, you must select one primary source. Read this source carefully several times. Identify a particular element, theme, or piece of information in the source and use that device to craft a 3-page paper on the primary source. Your paper should be driven by a clearly stated and well-defined thesis that posits an innovative argument, however subtle, for your source. You must then refer back to your source in order to provide supporting evidence for your thesis that you will analyze in the body of your paper. As when reading any source, be cautious of the temptation to take the text at face value. Read between the lines. In your analysis you may consider who produced the text and why? How did this person create the text and how was it received? Who was the intended audience? What may have been the purpose of the text and was it effective? It also may be relevant to consider the material elements of your source. How was it produced and preserved? Was it copied? Was it paired with other contemporary sources? Why might this source have survived for more than 800 years? You need not answer all or any of these questions directly but should consider them carefully in your analysis of this or any other source. 9 Assignment: Multiple Sources Paper Due: April 5 In the previous source assignment for this class, you considered a single primary source. The ability to read a source carefully, while essential to the historian, is ultimately an impossible approach to the writing of history. In addition to the internal textual and material context for the historical devices in a given source, a historian requires elements of context external to a source in order to fully understand it. These external elements could be social, economic, cultural, or a variety of other factors that allow us to make a boarder assessment of the place, and thus the meaning, of primary sources. But since these elements cannot be discovered by use of a time machine, a historian must depend on the ability to read sources in conversation with other primary sources to discover this external context. In this assignment, in consultation with your workshop instructor, you must select several sources (preferably 3-5 depending on the length of the sources). Read each of these sources carefully several times. Identify a particular element or theme common to all your sources and craft a 5-6-page paper on that common element. As with the first assignment, your paper should be driven by a clear thesis argument and supported by detailed analysis of each of your primary sources both in their own right and in conversation with each other. As when reading any source, be cautious of the temptation to take the text at face value. Read between the lines. In your analysis you may consider who produced the text and why? How did this person create the text and how was it received? Who was the intended audience? What may have been the purpose of the text and was it effective? It also may be relevant to consider the material elements of your source. How was it produced and preserved? Was it copied? Was it paired with other contemporary sources? Why might this source have survived for more than 800 years? You need not answer all or any of these questions directly but should consider them carefully in your analysis of these or any other sources. 10 Assignment: Research Proposal Due: May 4 This final paper asks you to use all the skills you have accumulated over the course of the semester to craft a research proposal based on the major themes of the workshop. Like any other paper, a research proposal should be driven by a central thesis; a core question that you intend to explore over the course of a much larger project. You should be able to break this core thesis into several composite parts, each of which you will amass a range of sources to explore and analyze in detail in a way that supports and complicates your core thesis and addresses your major historical questions. Research proposals are difficult to write and can take many shapes. Below are five basic guidelines to help you structure your proposal. 1. Provide a strong thesis statement based on logical, analytical, and innovative questions that you have devised for your chosen subject. Articulate this thesis in great detail exploring every way that you will support its argument. 2. Discuss the historiography of the topic. Who has worked on this topic before and how did they approach it? Go over all the relevant secondary sources you can find. In what ways does your proposal bring something different to the scholarly understanding of this topic? Be sure to consider why your topic has not been done before. Sometimes there is a gap in historical knowledge because access to the sources that would provide answers is simply impossible. Explain how your topic is possible, relevant, and will contribute to the field. 3. Explain the scope of your project. Where are the logical boundaries that will determine what sources you will use? Consider both the chronological beginning and end points of your project and its geographical constraints. How are you separating the information you will focus on from other information that may be related but occurring in a different time or place? 4. Write about the sources you will use. Where would you find them (name specific archives and repositories)? What language are they in? Have any been edited or published? Have any been translated? What has happened to the originals? And most importantly, why do you think these particular sources will provide the answers to your central research question? 5. Discuss your own approach to understanding these sources. This is especially true if other people have worked on these sources before. Explain what you will do differently. Do you have a particular theory or methodology? What theories do you have about what your sources will be able to tell you? 11 Instructions for Field Trip to the Rare Book Room For week 7 of this course (March 9), the day after the mid-term we will not be meeting in the usual room at NYU. We will instead meet at Colombia University's Rare Book and Manuscript Library (RBML)at Butler Library. In order to allow time for travel we will meet 30 minutes later. Listed here are some basic instructions for the trip. The trip is mandatory and all students will be expected to attend and have completed the readings for the week. Where to Go: The best way to reach Columbia is to take the number 1 subway uptown to 116th street. Butler Library is the large building in the center of the south end of the campus. Go through the library's main doors. To the left will be a small office. You will need to check in as a visiting student going to the RBML. They will have your name on a list. Then go into the library and to the hall way on the left toward the elevators. Take the elevator to the 6th floor and then turn right. We will meet there at the entrance to the RBML. What to Bring: You need only bring a pencil and some paper to this class. No pens, food, drinks, bags or cameras are allowed and personally belongings including coats are generally left outside or locked up. What You Will See: We will be taking a hands-on approach to understanding the way medieval books were created and used. The will examine a number of documents and manuscripts in Colombia's collection dating to the Middle Ages but if there is a specific piece you would like to see let me know ahead of time and it can be arranged. Check out the collection pages at: http://www.columbia.edu/cu/lweb/indiv/rbml/index.html and http://www.scriptorium.columbia.edu/ 12 A Guide to Research in Medieval History New York University Basic Tools for Historical Research www.jstor.org. The primary online site for scholarly journals. Many articles you find citations for will be available online here. The search function will also allow you to conduct research and find articles relevant to your topic. Note that the availability of specific journals varies, and some journals’ online availability is more recent than others. www.artstor.org Similar to jstor, but providing access to images of art in several types of media. Please carefully examine the reproduction rights of each image before using it. www.historycooperative.org. Another online site for journals, though less comprehensive than jstor and generally less useful for medieval studies. http://muse.jhu.edu. Project Muse, a large site for scholarly journals online. Many journals not available on jstor can be found here, and the emphasis is on more recent years. For monographs, RLIN and WorldCat tend to be the best searchable databases. Currently, I find Worldcat’s search engine produces better results, but it can also be unwieldy at times. Using Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH) can be a good way to quickly produce results, but not always. Interlibrary Loan. Allows you to obtain books and articles not available in Bobst. Follow the link at library.nyu.edu. In my experience, items may come as quickly as five days, and may take up to two weeks, with 7-10 days being the average. Not all items will be available, so be flexible in your expectations. Articles arrive as a free downloadable pdf file! For citations and formats, see A Manual of Style, 14th ed (Chicago, 2003). Overviews of the Field and Guides to Sources Boyce, Gray Cowan. Literature of medieval history, 1930-1975: a supplement to Louis John Paetow’s A guide to the study of medieval history (Millwood, 1981). Caenegem, R.C. van. Guide to the Sources of Medieval History. (Amsterdam and New York, 1978). Probably the best single-volume overview of sources for medieval history, but necessarily outdated at this point. 13 The New Cambridge Medieval History, ed. Rosamond McKitterick (Cambridge, 1995- ). 7 volumes divided up by chronological periods. Each volume contains numerous essays by a variety of scholars treating most of the major historiographical problems associated with each period, often with excellent suggestions for further reading. An excellent resource and generally up-to-date. Paetow, Louis John. A Guide to the Study of Medieval History (Millwood, 1980). Powell, James (ed.). Medieval Studies: An Introduction, 2nd ed. (Syracuse, 1992). Contains broad essays on major methodological issues in medieval studies, generally with useful bibliographies. Most of the essays will probably not be useful to you, but pending on your source base, you may find something of interest here. Typologie des sources du Moyen Âge occidental, series ed. Léopold Genicot (Turnhout, 1972). A large and ever-growing series. Each volume is dedicated to a specific form of source from the Middle Ages, covering topics from tree-rings to letter collections. Again, pending on your source base, there may be something of use to you here, but volumes are generally published in the author’s native language, and may be in French, German, English, or Italian. Repertorium fontium historiae medii aevi (Rome, 1962). Contains entries on many authors and sources from the Middle Ages, along with the works attributed to them and dates when possible. Covers more sources than van Caenegam, but less thoroughly. Can be difficult to use. Bibliographies International Medieval Bibliography (Minneapolis and Leeds, 1967- ). Now available online at www.brepolis.net (you must be connected to a subscribing server), this large and searchable bibliography covers articles published in both journals and edited collections from 1967 to the present. One of the most useful resources for medieval studies. Unfortunately, despite a recent overhaul, it is still not very user-friendly and requires some time and practice to use effectively. On the plus side, the new interface will automatically also search the Bibliographie de Civilisation Médiévale, a worldwide bibliography of monographs, and subject entries are now crossreferenced to the International Encyclopaedia for the Middle Ages (see below). Note: If you plan to use the IMB, start your searches early. A majority of the articles you find through this will not be available in Bobst, but if you begin your searches early you will be able to obtain them through interlibrary loan. Both the NYPL and Butler Library at Columbia will also have many of the articles not available at Bobst. Iter: Gateway to the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Available online at http://www.itergateway.org (subscribing servers only, once again). This enormous 14 bibliography includes articles, books, dissertation abstracts, entries in encyclopedias and book reviews. Cheyette, Fredric and Marcia Colish, “Section 20: Medieval Europe.” In The American Historical Association’s Guide to Historical Literature, eds. Mary Beth Norton and Pamela Gerardi. 2 vols. 3rd ed (New York and Oxford, 1995), vol. 1: 617-703. Solid guide to monographs organized by topic, but tends toward large synthetic works covering broad topics, and so may be less useful for specific research topics. Crosby, Everett, Julian Bishko and Robert Kellogg. Medieval Studies: A Bibliographical Guide (New York and London, 1983). Very useful. Feminae: Medieval Women and Gender Index. An online, searchable index of articles relating to the study of women and gender in the Middle Ages. Available at www.haverford.edu/library/reference/mschaus/mfi/mfi.html Many scholars publish bibliographies pertaining to particular subjects in medieval studies. They can be useful, but can also be idiosyncratic and limited. They also become dated very quickly. Typically, each bibliography indicates the specific years it covers. Here are some examples, though this list is by no means exhaustive: Berkhout, Carl T. and Jeffrey B. Russell. Medieval Heresies: A Bibliography, 1960-1979 (Toronto, 1981). Consoli, Joseph. Giovanni Boccaccio: an annotated bibliography (New York, 1992). Constable, Giles. Medieval Monasticism: A Select Bibliography (Toronto, 1976). Somewhat dated, but produced by the greatest North American scholar of monasticism. DeVries, Kelly. A Cumulative Bibliography of medieval military history and technology (Leiden, 2002, updated 2005). Ferguson, Carole. Bibliography of medieval drama, 1977-1980 (Emporia, 1988). Murphy, James. Medieval Rhetoric: A Select Bibliography (Toronto, 1971). Kren, Claudia. Medieval Science and Technology: A Selected, Annotated Bibliography (New York, 1985). Rosenthal, Joel Thomas. Late medieval England (1377-1485): a bibliography of historical scholarship, 1975-1989 (Kalamazoo, 1994). Sheehan, Michael M. Domestic Society in Medieval Europe: A Select Bibliography (Toronto, 1990). 15 Stratman, Carl Joseph. Bibliography of medieval drama, 2nd ed., rev. and enlarged (New York, 1972). Dictionaries and Encylopedias Dictionary of the Middle Ages, ed. Joseph Strayer (1982-89). 13 volumes of introductory articles dealing with a vast variety of topics relating to the Middle Ages, often with recommendations for further reading. One supplementary volume also appeared in 2004, edited by William Jordan, pertaining to new topics of research that have surfaced in the last 20 years. The Encyclopedia of Philosophy. ed. Paul Edwards et al. (New York, 1967). New Catholic Encyclopedia (New York, 1967- ). Particularly useful for dates, works attributed to particular authors, and some basic historical data. The perspective and bias should be clear, which leads to the glossing over of many scholarly debates, problems, and controversies. Encyclopeida of Early Christianity, ed. Everett Ferguson (New York, 1990). International Encyclopaedia for the Middle Ages – Online. Still in progress, as far as I know, but available online at www.brepolis.net (the same website as the IMB). Be warned, however, that this is a supplement to the Lexikon des Mittelalters, a German encyclopedia, and only has entries on those subject not covered there. Collections of Primary Sources In general, there are no large-scale collections of primary sources in translation, and so no single place to look. You will need to spend time hunting through the library for sources in translation. There are, however, some significant translation projects out there that may be of use. Note that none of these can substitute for library research. Farrar, Clarissa Palmer. Bibliography of English translations from medieval sources (New York, 1946). Ferguson, Mary Anne Hayward. Bibliography of English Translations from Medieval Sources, 1943-1967 (New York, 1974). I’m not familiar with either of these bibliographies, though they have the potential be extremely useful tools. Note: There appears to be an updating of these bibliographies on Stanford’s website, covering the year from 1971-1991: www-sul.standford.edu/depts/ssrg/medieval/engtrans.html. It looks very promising. 16 There are many publication series devoted to translating medieval sources. Among them I would particularly note: Medieval Sources in Translation, a series published by the Pontifical Institute of Medieval Studies at the University of Toronto. A full list of titles available in this series is available at http://pims.ca/publications/catalogue1.html#mst The Consortium for the Teaching of the Middle Ages (TEAMS) publishes several series of different types of sources in translation. The links to their various series can be found at http://www.wmich.edu/medieval/mip/books/teams.htm Cistercian Publications publishes a great many sources in translation relating to monastic history. Lists of these sources can be found at http://www.cistercianpublications.org. Follow the links for “Cistercian texts” and “Monastic texts.” I do not generally recommend the secondary sources published by Cistercian Publications, as their scholarly quality varies wildly. Several of the larger academic publishers have series devoted to medieval sources in translation, including Oxford Medieval Texts from Oxford University Press, Medieval Sources in Translation from Brepols Publishers, and the eponymous Penguin Classics series. Online Resources As always, online resources should be used with care. The Internet Medieval Sourcebook, edited by Paul Halsall. www.fordham.edu/halsall/sbook.html. Probably the single best online site for medieval sources. Contains links both to short excerpts of sources (generally for teaching) and full texts of translated sources (better for research). Please read the guidelines to citing sources from IMS provided on the website if you intend to use anything from it. The Online Reference Book for Medieval Studies (The ORB). www.the-orb.net/index.html. A wide-ranging site, somewhat difficult to navigate, but containing much good material, including both primary and secondary sources. I would confine yourself to use of the primary sources here. There are also large bibliographies organized by subject in the “What Every Medievalist Should Know” section, but I find them highly selective and idiosyncratic, with heavy emphasis on German historiography. The Labyrinth. http://labyrinth.georgetown.edu. Basically, a gateway site to other sites pertaining to medieval studies, organized by topic. You never know what you’ll find with Labyrinth, and it can be difficult to gauge the quality of the site you’ve been linked to. Netserf. http://www.netserf.org. Irritating, if wide-ranging, site, which I’ve never had much luck with. 17 The Index of Christian Art. http://ica.princeton.edu. One of the great online resources for medieval studies, though only useful if you are doing a project pertaining to objects of art. Nonetheless, check it out just for the sheer pleasure of it. 18