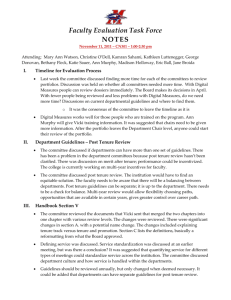

Organization and Bargaining with Adjunct, Part

advertisement

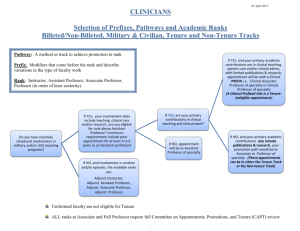

ORGANIZATION AND BARGAINING WITH ADJUNCT, PART-TIME AND NONTENURED FACULTY March 3 - 5, 2004 Atlanta, GA John B. Wolf1 Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey New Brunswick, NJ I. Who Are These People? A. Adjuncts B. Non-Tenure Track Faculty II Special Challenges in Organizing Campaigns A. Oral Solicitation B. Distribution of Literature C. E-Mail D. Union Access to Company Property E. First Amendment Issues Involving Access to Property F. Union Access to University Mail Systems G. Union Access to Names, Addresses and Telephone Numbers of Prospective Bargaining Unit Members III Community of Interest and Bargaining Unit Configurations IV Job Security for Adjuncts, Part-Time Faculty and Non-Tenure Track Faculty A. Define What is Meant by Job Security B. Non-Tenure Track Clinical Positions C. Course Assignments D. Tenure Quotas E. Retirement Policies; Transition Incentives F. Define What is Meant by “Just Cause” This paper highlights some of the legal issues and practical considerations applicable to organizing campaigns, negotiations and contract administration with adjunct faculty and other 1 The author is grateful for the research performed by Barbara McManus, Legal Assistant, and by Ted Eisenberg, Esq., managing partner of Grotta, Glassman and Hoffman, Roseland, N.J. that contributed to this paper. The views expressed are those of the author and not those of Ms. McManus, Mr. Eisenberg or Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey. National Association of College and University Attorneys 1 non-tenure track faculty. Special challenges confront unions in organizing campaigns because these employees often are part-time and spend little time on campus. Colleges and universities are faced with the challenge in negotiations of being asked, indeed pressured, to agree to terms that impair the flexibility provided by the use of adjunct, part-time and non-tenure track faculty. I. Who Are These People? A. Adjuncts Adjuncts, known by various titles, constitute a diverse group of positions in higher education. Most are part-time employees and may also be graduate students, even teaching assistants, at the same institution. These positions now are a focus of both organized labor and the national AAUP. The cover story (AThe New Academic Labor System@) in the January-February, 2004 issue of Academe discusses this part of the higher education work force. See also AAUP Policy Statement on Contingent Appointments and the Academic Profession, November 9, 2003, available at www.aaup.org/statements and “Standards of Good Practice in the Employment of Part-Time/Adjunct Faculty,” AFT website at www.aft.org/high__ed/parttime B. Non-Tenure Track Faculty Non-tenure track faculty often are full-time employees with single or multi-year appointments. Non-tenure track faculty often are full-time regularly appointed employees and, thus, may be regarded exactly like tenure track faculty, except with respect to eligibility for academic tenure. In other institutions, there are other significant differences between non-tenure track and tenure track faculty. Nontenure track faculty appointments may be used in a variety of areas where either there is no expectation of scholarship or where maximum flexibility in deployment of faculty is desired. They often are appointed in clinical practice areas in medicine, pharmacy, nursing, and law; and in business and the performing arts. National Association of College and University Attorneys 2 II. Special Challenges in Organizing Campaigns Because adjuncts and other non-tenure track faculty often are not regular employees, there are special challenges for unions seeking to organize them. Accordingly, the following issues may be more prominent in campaigns to organize these employees than in campaigns to organize regularly appointed employees. Multiple rights are involved in organizing campaigns. Campaigns involve labor law issues (state or federal), property right issues, public access and public forum issues, and free expression issues. The intersection of these issues can be complex. Generally, however, the following principles apply to union solicitation, distribution of literature and access to employer property: $ Employers may prohibit oral solicitations only during work time $ Employers may prohibit distribution of literature both during work time and in work areas (even when employees are not working) $ Employers are not required to allow non-employee access to their property unless there are no other means of accessing the employees $ Rules must be enforced in a non-discriminatory manner A Oral Solicitation In Republic Aviation Corp. v. NLRB, 324 U.S. 793 (1945), the Supreme Court balanced an employer=s property interest and the need to ensure uninterrupted work with the employee=s interests in seeking to gain support for a union. The NLRA does not prevent an employer from making and enforcing reasonable rules about the conduct of employees on company time. Therefore, an employer may prohibit union oral solicitation by employees during working hours, provided that the rule is enforced in a non-discriminatory manner (that is, applying to all solicitations, not just union-related solicitations). However, the Court also stated that an employer generally may not prohibit union solicitation by employees National Association of College and University Attorneys 3 outside of working hours, although on company property. B. Distribution of Literature In Stoddard-Quirk Mfg. Co., 138 NLRB 615 (1962), the NLRB distinguished between solicitation and distribution, stating that solicitation is only oral and impinges upon the employer=s interests only to the extent it occurs on work time, whereas distribution of literature may raise problems with littering the employer=s premises and a hazard to work operations whether it occurs on work time or nonwork time. Accordingly, a no-distribution rule properly can extend to work areas even on non-work time. However, a no-distribution rule that applies to non-work times in non-work areas is presumptively invalid. The Board conceded that while allowing employees to distribute literature in a non-work area is an intrusion upon an employer=s property rights, the intrusion is necessary in order to balance employee and employer rights. C. E-Mail The distinctions between employees= rights to speak to their colleagues versus distribute literature about union activities become increasingly hard to draw in the context of e-mail communications which share characteristics of both solicitation and distribution. Under Stoddard-Quirk, while an employer may not prohibit solicitation in work areas, the employer may prohibit distribution of literature there. Therefore, assuming e-mail constitutes a work area, the permissible restriction on its use will depend on whether e-mail is considered solicitation or distribution. At least some e-mail messages sufficiently carry the indicia of oral solicitation to warrant the same treatment as traditional oral solicitation. An example of such solicitation is when two employees have an interactive e-mail Aconversation@ in real time regarding the union=s organizing campaign, or some collective grievance, when both employees are not on work time. Pratt & Whitney, 1998 NLRB G.C.M. LEXIS 51, *17 (1998). National Association of College and University Attorneys 4 E-mail communications have been compared with other means of communication. E-mail messages, unlike telephone calls, do not have to be sent or read on working time and their postings do not hinder an employee from receiving workrelated communications. E-mail can be saved, read and responded to later, when the employee is not occupied by work. E-mail is unlike physical mail because the latter requires a workforce to handle, sort, and deliver the messages while e-mail does not. Despite arguments likening non-work e-mail to litter and complaints that non-work e-mail may clog and slow e-mail systems, it has been said that there is no danger that an e-mail system will run out of space if union communications were allowed. Prudential Insurance Co. of America, 2002 NLRB LEXIS 551, *16 (2002) Because employers cannot prohibit solicitation in work areas during non-work times, and because e-mail may be considered, at least in part, a solicitation taking place in a work area, a blanket prohibition on non-business related e-mail use may be unlawful. See Pratt & Whitney, supra. However, legitimate business concerns may justify some restrictions. For example, in TXU Electric, 2001 NLRB G.C.M. LEXIS 74, *13 (2001), an employer permitted personal use of the e-mail system, but limited the permissible length of the messages, attachments to messages and the number of employees to which any particular e-mail could be sent. While a blanket policy would be unlawful, the limiting policy here was facially lawful because it narrowly addressed the employer=s legitimate business concerns - to forestall significant interference with its use of the e-mail system while adequately balancing employees= rights. Employers cannot maintain restrictive e-mail policies which discriminate against union activities. Thus, the widespread use of e-mail for a variety of personal reasons will make uniform enforcement of Abusiness use only@ e-mail policies National Association of College and University Attorneys 5 difficult. See In E.I. du Pont de Nemours & Co., 311 NLRB 893, 919 (1993). Compare Guard Publishing Co. d/b/a/ The Register-Guard, 2002 NLRB LEXIS 70, *6 (2002), an employer’s policy prohibited use of its communications systems to solicit or proselytize for commercial ventures, religious or political causes, outside organizations, or other non-job-related solicitations. Because this was a non-discriminatory limitation on the use of the company’s equipment it was held not a facially overbroad no-solicitation/no-distribution rule, but rather a valid limit on the use of communications equipment. Similarly, in Adtranz, ABB DaimlerBenz Transportation, N.A., Inc., 331 NLRB at 291 (2000), the Board affirmed an ALJ decision in which the ALJ concluded that an employer may prohibit all personal use of its computers and e-mail system by employees so long as there is no discriminatory enforcement. D. Union Access to Company Property In NLRB v. Babcock & Wilcox, 351 U.S. 105 (1956), and Lechmere v. NLRB, 502 U.S. 527 (1992), the Supreme Court held that employers could not be compelled to allow non-employee union access to company-owned parking lots for distribution of union literature where (1) the employer did not discriminate against the union by allowing other distribution, and (2) other channels of communication were available to enable the union to reach the employees. Since union organizers in these cases had other means of access to employees, access to employer property was not required. See “Employer Solicitation Policies; Union Versus Charity,” 1 DePaul Business & Commercial Law Journal 449 (Spring 2003) From a practical standpoint, where colleges and universities have open campuses and often permit the presence of vendors, limiting union representatives will constitute unlawful discrimination. Lucile Salter Packard Children=s Hospital at Stanford v. NLRB, 97 F.3d 583 (D.C. Cir. 1996). These principles have been National Association of College and University Attorneys 6 applied in the public sector as well. California State Employees Association, SEIU v. State of California, 22 CAPERC & 29034 (ALJ), aff=d 22 CAPERC & 29148 (PERB 1998) E. First Amendment Issues Involving Access to Property In the public sector, there are First Amendment issues in addition to labor law considerations. In Perry Education Association v. Perry Local Educators= Association, 460 U.S. 37 (1983), the designated bargaining agent was granted exclusive access to an interschool mail system which constituted a Anon-public forum.@ The Supreme Court held that denial of access to the mail system by a rival union was reasonable and not based on content but on the status of one union as the exclusive representative. See also Old Bridge Board of Education, P.E.R.C. No. 87-51, 12 NJPER 844 (& 17324 1986) (union and public employers may negotiate over majority representative=s reasonable use of school mailboxes) Certain types of government property must be made available for expressive purposes under the public forum principles set forth in Perry. In “traditional public forums” (“quintessential public forums” such as streets and parks) speech cannot be restricted (except as to time, place and manner) unless a compelling governmental interest can be demonstrated and the restriction is narrowly drawn. A “designated public forum” is one that the government has opened to the public for expressive activity. So long as the government retains the open character of the public forum it is bound by the same standards applicable to a traditional public forum. “Non-public forums” are those government places which have not been, by tradition or designation, forums for public communication. The government may reserve these places for their intended purposes and may impose, in addition to time, place and manner restrictions, other reasonable regulations that are content neutral. (460 U.S. at 45-46) National Association of College and University Attorneys 7 Perry, however, does not apply to private property. In the private sector, the labor law principles described above apply. See Babcock & Wilcox, Lechmere and Salter, Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital, supra. F. Union Access to University Mail Systems The Federal Private Express Statutes prohibit carriage of union mail to University employees over U.S. postal routes without payment of postage to the U.S. Postal Service. Regents of the University of California v. Public Employment Relations Board, 485 U.S. 589 (1988) Thus, union proposals over access to interschool mail facilities have been held not subject to collective negotiations. Rockaway Township Board of Education and Ramapo-Indian Hills Regional High School Board of Education, unpublished decision, Superior Court of New Jersey, Appellate Division, DKT. Nos. A-5542-89T5 and A-5535-89T1 (consolidated cases) (March 25, 1991), affirming P.E.R.C. Nos. 90-107 and 90-104, 16 NJPER 321 and 313 (& 21132 and & 21129 1990) However, while sending union mail through a school district=s mail system generally violates federal Private Express Statutes, mailing union communications concerning joint labor-management committees that administer school or employee benefits programs – as opposed to bargaining over them - may be permitted. Fort Wayne Community Schools v. Fort Wayne Education Association, 977 F.2d 358 (7th Cir. 1992), cert. den., 510 U.S. 826 (1993) G. Union Access to Names, Addresses and Telephone Numbers of Prospective Bargaining Unit Members This is an area where labor law intersects with privacy interests and public records statutes. Thus, under federal labor law, it has been held that an employer=s duty to bargain in good faith includes a duty to disclose to the union bargaining unit names, but not home addresses. Grinnell Fire Protection Systems v. NLRB, 272 F.3d 1028, 168 LRRM 2976 (8th Cir. 2001) Under a state right-toNational Association of College and University Attorneys 8 know statute an aspiring union was entitled to names and campus addresses of part-time faculty and, in addition, to campus telephone numbers and home mailing addresses under state common law. Part-Time Faculty Chapter, Rutgers Council of AAUP Chapters v. Rutgers, unpublished decision, Superior Court of N.J., Appellate Division, DKT. No. A-432488T1 (April 6, 1990) Compare Miami Valley Child Development Center v. SEIU/AFL-CIO, 170 LRRM 3012 (Ohio App. 2 Dist. 2002) (union not entitled to home addresses of employees of Head Start Child Development Center) While disclosure of home addresses ordinarily would constitute an invasion of privacy, addresses of state-employed physicians who used home addresses as their Aaddress of record@ were not exempt from disclosure under the California Public Records Act. Lorig v. Medical Board, 92 Cal. Rptr. 2d 862 (App. 1 Dist. 2000) Similarly, names and mailing addresses of plumbers licensed by the Department of Public Health were not personal information exempted from disclosure under the State Freedom of Information Act. Chicago Journeymen Plumbers= Local Union 130 v. Department of Public Health, 327 Ill. App. 3d 192, 761 N.E. 2d 1227 (App. 1 Dist. 2001) III. Community of Interest and Bargaining Unit Configurations An appropriate bargaining unit must consist of employees who share a community of interests. Factors considered in determining whether a community of interest exists are: $ $ $ $ $ similarity of duties, skills, interests, and working conditions similarity of wages, compensation system and benefits organizational structure of institution expressed desires of employees history of past bargaining (if any) See Developing Labor Law, The Third Edition, Patrick Hardin, ed, Bureau of National Affairs, Wash., D.C. 1992, Chapter 11. An extensive discussion of the community of interest adjunct bargaining cases is contained in “The Indentured Servants of Academia: The Adjunct Faculty Dilemma and Their Limited Legal National Association of College and University Attorneys 9 Remedies,” 74 Indiana Law Journal 513 (Spring 1999). The cases illustrate the case-by-case community of interest analysis and the awkward and inconsistent configurations that result. Adjunct faculty typically are in their own bargaining unit. Adjunct faculty who are hired semester by semester to teach specialty courses and additional sections of commonly offered courses are Aemployees@ under state labor law, but they do not share a community of interest with full-time faculty. Vermont State Colleges Faculty Federation v. Vermont State Colleges, 152 Vt. 343, 566 A.2d 955 (1989) Adjunct faculty, however, may be represented in a separate bargaining unit by the same union that represents full-time faculty. Vermont State Colleges Faculty Federation, AFT Local 3180 v. Vermont State Colleges, 159 Vt. 619, 616 A2d 221 (1992) This is the case, also, at Rutgers where the one AAUP bargaining unit includes all faculty (tenure track and nontenure track) and teaching assistants/graduate assistants, and a separate chapter represents the part-time lecturer (i.e., adjunct) bargaining unit. See also Somerset County College, P.E.R.C. No. 87-129, 13 NJPER 361 (& 18150 1987), aff=d NJPER Supp.2d 185 (& 164 App. Div. 1988), aff=d S.Ct. Dkt. No. A-60 (1/24/89) (per course instructors at New Jersey county college, many of whose primary occupations were elsewhere, who commenced employment for at least their second semester during a given academic year and who expressed a willingness to be rehired to teach at least one semester during the next academic year, shared a sufficient community of interest to constitute an appropriate unit for collective negotiations); State of New Jersey and Council of New Jersey State College Locals, P.E.R.C. No. 97-81, 23 NJPER 115 (& 28055 1997) (statewide unit of approximately 2300 adjunct faculty employed at seven state colleges and one state university in New Jersey who commenced employment for at least their second semester within the past two academic years and who expressed a willingness to be rehired shared a community of interest and constituted an appropriate negotiations unit) National Association of College and University Attorneys 10 Tenure track and non-tenure track faculty may share a community of interest and be combined in the same bargaining unit. In Michigan Technological University, 6 MPER & 24074 (1993), a combined unit of tenure track and non-tenure track faculty was held appropriate where job responsibilities were similar, both participated in University governance, most fringe benefits were identical and there was day-to-day contact and functional integration of their work. At Rutgers University, clinical track and other non-tenure track faculty are in the same bargaining unit with regular tenure track faculty. Compare Wright State University Chapter of AAUP and Wright State University, 15 OPER & 1091 (H. Off. 1997). (Hearing Officer found petitioned for unit appropriate consisting of full time tenured and tenure track faculty, but excluding faculty in schools of medicine and professional psychology who are not eligible for tenure, where university sought broader unit including non-tenure eligible Afully affiliated@ faculty) Mixed bargaining units with faculty and non-faculty also have been approved. In Sandburg Faculty Association v. Illinois Educational Labor Relations Board, 248 Ill. App.3d 1028, 618 N.E.2d 989, 188 Ill. Dec. 419, 144 LRRM 2543, 85 Ed. Law Rep. 79 (1993), a community colleges=s small campus environment supported enlarging an existing collective bargaining unit of 50 faculty members and counselors to include 45 non-faculty who performed secretarial, maintenance and security duties. In Henry Ford Community College, Henry Ford Community College Administrators Association and Henry Ford Community College, Federation of Teachers, AFT, 9 MPER & 27086 (1996), a newly created instructional technologist position whose mission was to facilitate and promote instructional technology was functionally integrated with faculty and, thus, shared a community of interest with the faculty bargaining unit. In Grand Rapids Community College and Grand Rapids Community College Faculty Association, 9 MPER & 27039 (1996), vocational-technical instructional personnel at a laboratory preschool, whose duties were to supervise and evaluate students seeking degrees in child development while they work with National Association of College and University Attorneys 11 children, were accreted to an existing faculty bargaining unit comprised of academic instructors. In Ocean County College and Ocean County College Faculty Association, D.R. No. 95-8, 21 NJPER 4 (& 26002 1994), a faculty unit was clarified to include coordinator and director positions where their duties were an extension of faculty functions and where positions were filled by faculty. Where the coordinator and director positions were filled by adjunct faculty, the adjunct faculty union could petition separately to include them in the adjunct bargaining unit. A fundamental issue in any collective bargaining relationship is who is included and who is not included in the bargaining unit. Concerns about the bargaining unit configuration begin with the filing of a representation petition. If a bargaining agent is elected and a contract eventually settled, issues still may arise in the future when new positions are created and when existing positions are merged, realigned or eliminated. In this regard, attention should be paid to the titles that are attached to positions and to the clarity with which job responsibilities are defined. While unions may use generously the term Afaculty member@ to apply to any person who participates in instructional activity, there is no need for the institution to use a title if it connotes privileges or responsibilities that do not apply. Thus, adjuncts and other part-timers may be designated as Astaff” rather than Afaculty.@ In Rutgers University, P.E.R.C. No. 91-81, 17 NJPER 212 (& 22091 1991), PERC permitted negotiations by the union representing AVisiting Part-Time Lecturers@ (instructional staff employees hired and paid by the course, known more commonly elsewhere as “adjuncts” or “adjunct faculty”) over a proposal to change their title to APart-Time Lecturer@ because no new title or duties would be created. Over time, the Astaff@ designation for PTLs has eroded at Rutgers. While the union representing these per course instructors is called the Part-Time Lecturer Chapter of the Rutgers Council of National Association of College and University Attorneys 12 AAUP Chapters, the contract contains the following language that serves to lessen the distinction between the regular faculty and PTLs. Departments shall advise PTLs of the campus location where their mail, notices, and other communications will be available. Departments are encouraged to consider PTLs to be a part of the faculty and provide them with relevant information, announcements, and communications, including all communications addressed to AMembers of the University Community.@ IV. Job Security for Adjuncts, Part-Time Faculty and Non-Tenure Track Faculty Any form of “just cause” protection including academic tenure, typically involves 3 things. First, it provides continued or permanent employment subject to termination only for prescribed reasons. Second, it provides some form of pre-termination procedural safeguards. Third, “just cause” protections in the collective bargaining context typically involve some form of post-termination appeal. The focus in this section is on whether there should be job security for adjuncts, part-time faculty and non-tenure track faculty and, of so, what it should look like. Distinctions have been made between job security for non-professional employees and academic tenure for faculty members. In negotiating over union demands for job security, colleges and universities should consider whether there are educational policy reasons why job security or academic tenure should not be within the scope of negotiations or, if they are, why an institution might not agree to these demands. A. Define What is Meant by Job Security In the collective bargaining context, the parties can define their own terms and they can qualify whatever job security provisions they create. If they do not clearly define their terms, they leave the meaning, typically, to a neutral third party - an outsider who will apply his notion of justice based upon experiences that may or may not be relevant to a higher education context. Job security should be considered in the context of at least three different circumstances: misconduct or bad behavior conduct related to job performance restructuring or reorganization (due to academic or budgetary needs) National Association of College and University Attorneys 13 While unions would seek the same protections in all three situations, colleges and universities have every right to seek to treat job security differently depending upon the circumstances. Clearly, negotiated provisions that limit the issue in a posttermination dispute resolution forum to whether a college’s decision based on honestly held reasons is better than provisions that permit a third party to decide whether those reasons were justified. New Jersey Courts and New Jersey’s PERC have addressed job security in higher education in a variety of contexts. B. Non-Tenure Track Clinical Faculty Positions In Rutgers University, P.E.R.C. No. 2000-83, 26 NJPER 209 (& 31086 2000), the University refused to negotiate over the creation of non-tenure track clinical faculty positions in nursing and pharmacy. PERC held that the University could act unilaterally because this was a non-negotiable educational policy decision. PERC said: …given the University’s unfettered right to set criteria for academic tenure, it cannot be forced to negotiate over making academic tenure available to employees without the requisite scholarship… In other words, if Rutgers decides that academic tenure requires scholarship and that a particular faculty title should not emphasize scholarship, then an agreement to make that title tenure eligible would significantly interfere with an educational policy determination. (26 NJPER at 212) PERC noted, however, that other forms of job security may be negotiable. Compare Wright v. Board of Education of City of East Orange, 99 N.J. 112, 491 A.2d 644 (1985) (statutory tenure provision for school custodians does not preempt all negotiations over custodial tenure); Plumbers and Steamfitters v. Woodbridge Board of Education, 159 N.J. Super. 83, 386 A.2d 1369 (1978) (job security is a term and condition of employment; tradesman without statutory tenure may negotiate job security and protection from unfair or unwarranted dismissal) C. Course Assignments National Association of College and University Attorneys 14 Articulating clearly reasons why job security interferes with the development or implementation of educational goals or policies is necessary to avoid becoming burdened with job security provisions that limit an institution’s flexibility to hire and retain the most qualified personnel to teach, and to assign to particular courses the most appropriate individuals. In Rutgers University, P.E.R.C. NO. 91-812, 17 NJPER 212 (& 22091 1991), PERC held that a union proposal that part-time lecturer appointments come from a list of existing PTLs was negotiable because the proposal included an exemption that would allow the University to deviate from the list for educational policy reasons. PERC said: Rutgers has an uncontested right to decide what courses to offer, how many sections of a particular course will be offered, when they will be offered, and whether VPLs will teach them. But the question of whether Rutgers can agree to have a pool of qualified lecturers available to teach offered courses implicates job security. In deciding whether a particular proposal predominately involves educational policy or job security, we must weigh the nature of the term and condition of employment against the extent of its interference with that policy. * * * To examine the limits of negotiability in this area, we must distinguish between the decisions to hire, reappoint and assign. Rutgers has a prerogative to hire employees. But once hired, those employees may be protected by a job security provision which affords their employer an opportunity to evaluate their performance before tenure is granted… Whether or not the employees have negotiated job security, Rutgers must also retain its prerogative to assign particular teachers to particular courses. * * * It [the union’s proposal] does not restrict Rutgers= National Association of College and University Attorneys 15 right to deviate from the list for major educational policy reasons. It is a limited job security provision, providing a right to be considered for continued employment to those who have already taught at least two semesters, but preserving Rutgers= right to deviate from the list for major educational policy reasons. Those reasons include judgments about academic qualifications and thus the sentence does not prevent the employer from appointing from off the list and does not significantly interfere with the determination of governmental policy. (17 NJPER at 214 and 216) Accord, Rutgers, The State University, 6 NJPER 546 (& 11277 PERC 1980) (while job tenure and seniority are negotiable in the abstract, whether proposal concerning job security of coadjutant faculty might interfere with University=s ability to assign best suited individuals to teach particular courses required evidentiary hearing). D. Tenure Quotas Tenure quotas and long range staffing plans are examples of broad-based policies that impact job security of individual employees but that, nevertheless, have been held to be outside the scope of collective negotiations. In Association of New Jersey State College Faculties v. Dungan, 64 N.J. 338, 316 A.2d 425, 85 L.R.R.M. 2625 (1974), resolutions of the Board of Higher Education regarding tenure policies at the State Colleges and County Colleges were challenged by faculty unions as having been promulgated without collective negotiations. The policies addressed the balance between tenured and non-tenured faculty; criteria for reappointments conferring tenure; and standards of performance warranting tenure. The Court held that the policies involved major educational policy issues and were not subject to collective negotiations even though the granting of tenure involved consequences to individual faculty members. In State of New Jersey (Stockton State College), P.E.R.C. No. 76-33, 2 NJPER 147 (1976), the College adopted a Ten-Year Faculty Staffing/Tenure Plan that dealt with the issue of the proportion of tenured faculty to non-tenured faculty. The union sought to negotiate these proportions and National Association of College and University Attorneys 16 specifically argued that tenure was a form of job security and that the plan had significant consequences for individual faculty members. PERC rejected the union's argument and held that the Plan was not negotiable. PERC said: The Council [union] notes that tenure as a concept was originally created to provide job security - an aspect of the job which intimately affects the public employee. The Stockton Tenure Plan, however, by imposing quotas on tenure, is a means of denying job security. The Council concludes that as the Plan constitutes a prior determination as to job security, it affects the terms and conditions of employment and should be a required subject for negotiations... We conclude that Stockton State College should be free, in the exercise of its educational responsibilities... to determine those tenure limits which will encourage maximum flexibility in educational programs and maximum utilization of pedagogical skills. The extent to which tenure and the unique protections accorded its recipients is regulated by the instant tenure ratio policy has profound implications for the quality of the Stockton State College educational program. Such decisions should not be subject to the mandatory negotiations process and we so find. (2 NJPER at 149) E. Retirement Policies; Transition Incentives In University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey v. AAUP, 223 N.J. Super. 323, 538 A.2d 840 (App. Div. 1988), aff’d 115 N.J. 29, 556 A.2d 1190 (1989), the Court balanced the interests of the University against those of the faculty and held that the University’s interests in deploying faculty and allocating faculty resources predominated even where faculty members were required to retire, losing their tenure and their jobs. The Court held that whether to force a tenured professor to retire at age 70 was a non-negotiable subject. The Appellate Division said: we find that dominant concern underlying the decision to retire an individual at age 70 is how the institution can best achieve its mandated educational purpose. It implicates important tradeoffs between the desire of an individual to continue working and the expertise which he provides versus an institution’s need to National Association of College and University Attorneys 17 bring in new faculty, to deploy its faculty in different academic areas and to open up tenure and promotional positions in order to retain its current faculty and to afford equal employment opportunities… Nothing could be more germane to the educational goals of an institution of higher education than the vitality of that institution as reflected in its ability to hire, retain and deploy its faculty. (223 N.J. Super. at 334-336) F. Define What is Meant by “Just Cause” As noted earlier, if there needs to be a form of job security for adjunct, part-time faculty or non-tenure track faculty, the goal is to secure a standard by which the employer can make judgments about professional performance and about programmatic needs that cannot be second-guessed by those not accountable for the quality of the institution=s academic enterprise. Accordingly, the following formulations of “just cause” provide limitations that preserve institutional flexibility and that limit the authority of a third party neutral. where the job is not being performed safely and effectively, or where there is substantial objective evidence of poor job performance. Greenwood v. State Police Training Center, 127 N.J. 500, 509-511 (1992). a real cause or basis... as distinguished from an arbitrary whim or caprice - that is, a cause or ground that a reasonable employer, acting in good faith... would regard as a good and sufficient reason... Fried v. Aftec, Inc., 246 N.J. Super. 245, 255-256 (App. Div. 1991) a reason pertaining to the leadership, performance or ability of an employee to discharge his/her duties that the employer reasonably believes calls into question the fitness of an employee for a particular job; a legitimate business concern that the employer genuinely subjectively believes; a fair and honest reason supported by substantial evidence; National Association of College and University Attorneys 18 a legitimate academic, economic or business reason that is not arbitrary; a reason that, given all of the applicable facts and circumstances, is fair and reasonable. An excellent review of tenure from a legal and administrative viewpoint, with a discussion of the reasons why tenure can be terminated, was prepared by Thomas P. Hustoles, frequent NACUA speaker and partner with Miller, Canfield, Paddock and Stone, P.L.C., Kalamazzo, Michigan, for the 12th Annual Legal Issues in Higher Education Conference at the University of Vermont, 2002. National Association of College and University Attorneys 19