Issues in the Sustainable Management of Protected Areas of Nepal

advertisement

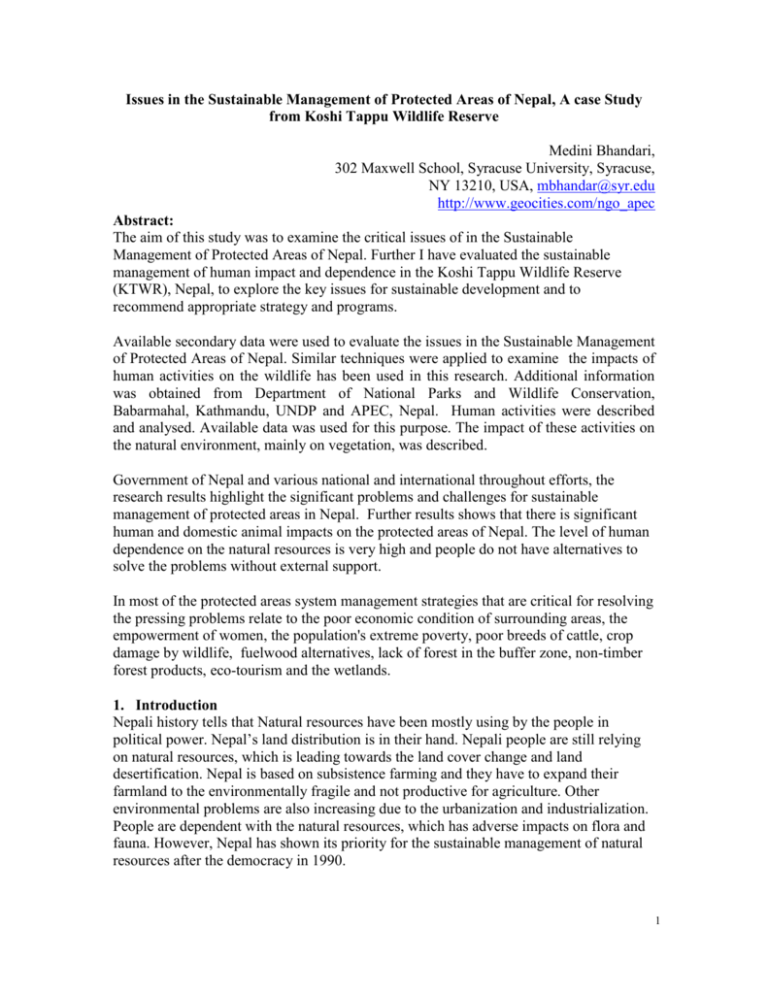

Issues in the Sustainable Management of Protected Areas of Nepal, A case Study from Koshi Tappu Wildlife Reserve Medini Bhandari, 302 Maxwell School, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY 13210, USA, mbhandar@syr.edu http://www.geocities.com/ngo_apec Abstract: The aim of this study was to examine the critical issues of in the Sustainable Management of Protected Areas of Nepal. Further I have evaluated the sustainable management of human impact and dependence in the Koshi Tappu Wildlife Reserve (KTWR), Nepal, to explore the key issues for sustainable development and to recommend appropriate strategy and programs. Available secondary data were used to evaluate the issues in the Sustainable Management of Protected Areas of Nepal. Similar techniques were applied to examine the impacts of human activities on the wildlife has been used in this research. Additional information was obtained from Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation, Babarmahal, Kathmandu, UNDP and APEC, Nepal. Human activities were described and analysed. Available data was used for this purpose. The impact of these activities on the natural environment, mainly on vegetation, was described. Government of Nepal and various national and international throughout efforts, the research results highlight the significant problems and challenges for sustainable management of protected areas in Nepal. Further results shows that there is significant human and domestic animal impacts on the protected areas of Nepal. The level of human dependence on the natural resources is very high and people do not have alternatives to solve the problems without external support. In most of the protected areas system management strategies that are critical for resolving the pressing problems relate to the poor economic condition of surrounding areas, the empowerment of women, the population's extreme poverty, poor breeds of cattle, crop damage by wildlife, fuelwood alternatives, lack of forest in the buffer zone, non-timber forest products, eco-tourism and the wetlands. 1. Introduction Nepali history tells that Natural resources have been mostly using by the people in political power. Nepal’s land distribution is in their hand. Nepali people are still relying on natural resources, which is leading towards the land cover change and land desertification. Nepal is based on subsistence farming and they have to expand their farmland to the environmentally fragile and not productive for agriculture. Other environmental problems are also increasing due to the urbanization and industrialization. People are dependent with the natural resources, which has adverse impacts on flora and fauna. However, Nepal has shown its priority for the sustainable management of natural resources after the democracy in 1990. 1 1.2. Nepal’s Sustainable Development problem Extreme Poverty, alarming rate of population growth, lack of developmental infrastructure (transportation, communication) illiteracy, landlocked, high terrain are key problems of sustainable development in Nepal. There is very high dependency and pressure on natural resources mainly on forest and wetlands. People are fully dependent on forest product for firewood, building materials, fodder and grass. There is no designated grazing land in particular; therefore, people take their cattle to the forest for grazing. Subsistence farming is the basis of life, so people are fully dependent on arable land. Other problems of sustainable management / development of Nepal are listed in the following paragraphs. Difference between government policy paper and actual work, there is no strong commitment from the government to sustainable development; Decisions always have been made without consultation of policy guidelines and experts. Country’s experts cannot force to change the government decision; decision is always driven by political benefit and motives. Decision always comes from capital making and lack of commitment to implementing the decentralized governance system; by principal decentralization provision is there There is no stakeholder participation in any level of development. Implementation is imposed like trickle down process Rural and local level problems are not correctly addressed Most of the programs are in theory and have practical base. When they implement such program they often fail to get expected result. No proper System of evaluation and monitoring, lack of sequence in policy and program and implementation No good coordination between developmental agencies, NGOs and Government agencies in different sectors and at different levels; Corruption no transparency and accountability from higher to lower level of key stakeholders for sustainable development 1.3 Other Issues To manage this ecosystem in a sustainable way, it is necessary to have up-to-date information concerning the ecosystem. Socio-economic data is needed as well as biophysical data, because the human impacts related to the poverty of the population are significant. Before this research, statistics concerning the ecosystem and spatial aspects had not been collated. Managers need to integrate both spatial and temporal information concerning the ecosystem and how specific activities might have consequences for the ecosystem in the future. HMG-Nepal and various NGOs and development agencies have completed substantial descriptive and analytical research on the reserve. However, the research outputs are neither complete nor holistic and are not applicable for all the policy management decisions that need to be made for the reserve. 2 There is insufficient research on the habitat of wild animals in eastern Nepal as well as on the socio-economic factors. Local people are living in the nearby areas of wildlife habitat and the human population is increasing by 3.5% annually (Bhandari, 1995). Their activities: agriculture, fuel wood collection, grass collection for domestic animals, and thatch material collection for house construction, cause major degradation of habitat and are influencing the distribution of the wildlife. It has been observed that wild animals including wild buffaloes are dependent on the lower soft and higher elephant grass. There is extreme pressure by domestic buffaloes on the park and they are creating unnecessary competition for the other wild animals in the reserve (Bhandari, 1994, 1995). Due to an increase in human activities resulting in degradation of forest and grassland, the habitat for wildlife is reducing in size. Logging for timber and fuel wood collection by the local villagers results in the reduction of habitat for biodiversity. There is also a lack of monitoring of these activities and to what extent they endanger the natural resources. The use of heavy vehicles for the construction of spurs (check dams) may have considerable impact on the wildlife habitat but has not been studied. Other problems in the (general) area are: a. An increase of human population in the forest area b. Deforestation c. Increased numbers of domestic animals in nearby villages d. Illegal poaching 1.4 Methods Available secondary data were used to evaluate the Issues in the Sustainable Management of Protected Areas of Nepal. Similar techniques were applied to examine the impacts of human activities on the wildlife has been used in this research. Additional information was obtained from Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation, Babarmahal, Kathmandu, UNDP and APEC, Nepal. Human activities were described and analysed. Available data was used for this purpose. The impact of these activities on the natural environment, mainly on vegetation, was described. 2. Result and discussion: 2. 1 Nepal Priority for Sustainable Development: Nepal has given priority to sustainable development. Due to the extreme poverty the sustainable management issues are presently overshadowed by political crisis, insecurity and various other problems. However national plans, laws and policy documents state Nepal’s commitment to sustainable development. The HMGN/NPC/MOPE 2003, Sustainable Development Agenda for Nepal, proclaims: 3 “The goal of sustainable development in Nepal is to expedite a process that reduces poverty and provides to its citizens and successive generations not just the basic means of livelihood, but also the broadest of opportunities in the social, economic, political, cultural, and ecological aspects of their lives. This begins with the pursuit of increased per capita income afforded by a stable population size that generates a viable and environmentally sound domestic resource base to create and nurture institutions of the state, markets, and civil society, whose services can be accessed equitably by all Nepalis. Basic development processes are to be overseen by accountable units of government with representation of women and men of all ethnicity and socio-economic status, whose management of resources, including the environment, is to be governed by an imperative that the ability of future Nepali generations to sustain or improve upon their quality of life and livelihoods is kept intact. A corollary inherent in viewing sustainable development in Nepal in these broad terms is a national resolve to pursue happy, healthy, and secure lives as citizens who lead a life of honor and dignity in a tolerant, just and democratic nation”1. In relation to land issues and natural resource management, the priorities and goals are clear and they represent the government’s commitments. According to the HMGN/NPC/MOPE 2003, Sustainable Development Agenda for Nepal, priority has to be given to resource base ecosystem management: “Land use is planned and managed at the local and national level such that resource bases and ecosystems are improved, with complementarity’s between high- and low- lands, that forest biomass grows, that agricultural and forest lands are protected from urban sprawl, and that biodiversity is conserved at the landscape level by recognizing threats from habitat fragmentation and loss of forest cover, a system of protected areas (including national parks and conservation areas) is maintained and further developed to safeguard the nation’s rich biodiversity. Local communities near protected areas are involved in both the management and economic benefit sharing of the area”2. The sustainable development policy document of Nepal has set the first priority with the consideration of its geo-physical, socio-economic and political situation. More than 40% of people are below the poverty line; therefore first priority is given to increasing the per capita income. Population growth rate is 2.25%, birth rate 33.4 births/1000 population, death rate 9.6/1000 population and life expectancy is 59.7 years (CBS 2001). In keeping with these facts, the second priority for sustainability is Health, Population and Settlements. On the basis of the variety of natural resources and the biophysical assets of the country Forests, Ecosystems and Biodiversity takes third priority. Education, Institutions and Infrastructure, and Peace and Security are other agenda priorities of the Government of Nepal. In this research I highlight the Forests, Ecosystems and Biodiversity issue. Fast degradation of forestland is a post 1950’s phenomenon. During the 1950’s, nationalization of forests took place, leading to the removal of the ownership and His Majesty’s Government of Nepal, Singha Durbar, Kathmandu Nepal 2002 Citation: HMGN/NPC/MOPE 2003, Sustainable Development Agenda for Nepal, Page 1-32 1 2 ibid, page 24 4 management of the resource base away from villagers without changing the demand for forest products. Since then the forest cover has been declining. In 1964 forest cover was 45% and in 1994 it was only 37% (CBS 1994, p32-33). Due to the variation of different terrain and altitude from 100 m from sea level to the mountains up to 8848 m, Nepal is unique with regard to biodiversity and different ecosystems. Protected mammals of Nepal include the Royal Bengal Tiger, Snow Leopard, Spotted Leopard, the Asian One-Horn Rhinoceros, the Asian Elephant, the Gangetic Dolphin, the Grey Wolf, the Assamese Monkey, the Wild Water Buffalo, Wild Yak, the Red Panda and the Pangolin, to mention a few. All together 181 species of mammals are found in the country. The country is also rich in bird life, with 844 species. Nepal has 118 types of forest ecosystems and it is inhabited by 9.3% of the world’s bird species and 4.5% of the world’s mammal species. Over 100 species of reptiles live in the country, including the Gherial Crocodile. Together with 635 species of butterflies and 185 species of fish, this is truly a country where nature is at its peak in diversity. The species of trees and plants are also high, amounting to about 5000, while 342 species of plants and 160 species of animals are considered to be endemic to Nepal. Also the agricultural diversity of Nepal is high, with a high variation among crop species like rice, rice bean, buckwheat, soybean, foxtail millet, and many fruit and vegetable species.1 Forests provide firewood and animal fodder (among many other products), and animals provide milk and meat, as well as fertilizer for the fields.2 2.2 Nepal’s commitment to the sustainable development process Nepal’s history shows that there was knowledge about the importance of nature and its contribution. Nepal rulers used the Hindu and Buddhist mythology to rule the country and followed the Hindu and Buddhist religions, traditions and culture. According to these mythologies, all living beings have equal importance in the eye of God. Humans are the supreme creation of God and they should honor and protect the creation of God. “Nepal is in this sense a very special country, with both Buddhism and Hinduism contributing to respect and reverence of nature. In addition several indigenous communities in Nepal have their own traditional beliefs of some witch stress the human dependence on nature. This is probably among the important factors behind the impressing conservation efforts in the country, in only a few decades. In Buddhism the attitudes towards animals and plant life are given in the Five Precepts (panca sila). The first precept involves abstention from injury to life. In the Karaniyametta Sutta, there are instructions in the cultivation of loving-kindness toward all creatures including visible as well as invisible. Buddhism also regards plants and trees highly, especially long lived trees. One legend tells how much compassion Buddha felt for two hungry tiger cubs, so much in fact, that he gave of his own flesh to feed them. Both Hinduism and Buddhism teach that humans are part of nature not above it. Human beings have no right to kill other creatures and exploit other natural resources except. Hinduism as well as Buddhism with their reverence for sacred mountains, sacred rivers, forests and animals has always been close to nature. The Geeta are rich in explaining the aspects of environment and conservation. According to Hinduism; "All religions are part of the 1 2 HMGN/MFSC 2002. Nepal Biodiversity Strategy, p. 2-32 HMG/NPC/MOPE. 2003. Sustainable Development Agenda for Nepal, p36. 5 processes of discovering the unity of God, Humanity and Nature".3 According to Hindu Mythology there are 330000000 Gods and Goddesses and each of them has relations with wild flora and fauna. Likewise there is a long list of god and goddess. Apart from these the sources of water land have different identity as god. Indigenous / ethnic community has also their many gods for conservation of nature.4 Gods and Goddesses and their association with plants and animals: Goddess Bagabati (goddess of power) Lion/ tiger Red flowering tree Lord Shiva (God of law) Bull Poisonous plant Vishnu (God of protection) Stroke (Garuda) Ficus religiosa Saraswati (Wisdom and knowledge) Swan and peacock Lotus Laxmi (Goddess of wealth) pair of Elephant Lotus Ganesh (the combination of power Wealth and wisdom) Rat Sandilon dectilon Yama (God of death) Wild water buffalo Bamboo This reverence for nature may have helped Nepal towards the sustainable management of natural resources in the past. 2.3 Current scenario and Nepal’s commitments on sustainability In its current commitment to sustainable development, Nepal has participated in international conferences since 1968, the First International Conference for Rational Use and Conservation of the Biosphere, Paris, France. Nepal supported the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment (Stockholm, Sweden; known as Stockholm Conference-1972), whose mission was “to provide leadership and encourage partnership in caring for the environment by inspiring, informing, and enabling nations and peoples to improve their quality of life without compromising that of future generations” (Sharma 2002). Nepal also acknowledged the report of the World Commission on Environment and Development (Brundtland Commission) and prepared its national plan incorporating the recommended issues of the commission report (1983). Since then, Nepal participated in most of the international conferences from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; Earth Summit 1992 to World Summit on Sustainable Development, Johannesburg, South Africa, 2002. On the basis of documentation, plans and commitments to the international conventions and treaties, Nepal has shown its great interest in the sustainable management of natural resources. However, there is a gap between the theory and real practice. 3 Facts on the nature of Nepal: This article is a brief introduction to some of the main environmental issues of Nepal, covering everything from poaching and biodiversity, to climate change and the impact on nature of the war. (06/04/2003) http://www.nepalfacts.org.np 4 Bhandari, M 2003, How Hindu mythology helps to protect our Environment, unpublished article. 6 Policy Documents and Plans Addressing Sustainable Development Issues in Nepal Eighth Five Year Plan 1992-1997. Poverty alleviation, with emphasis on environmental protection. Recognized NGOs as a driving force for development for the first time. NPC NEPAP I: Nepal Environmental Policy and Action Plan NEPAP II: Environmental Strategies and Policies for Industry, Forestry and Water Resources. Initiated in 1993, developed in 1996, implemented in 1998. Broad priorities to address environmental challenges in key natural resource and development sectors. Introduced principles of Agenda 21. Identified detailed action plans for key sectors, as well as cross-sectoral priorities. Prepared by IUCN Nepal for the EPC. Prepared by IUCN Nepal for MOPE. Agriculture Perspective Plan (APP) 1995. Aimed to increase agricultural productivity and reduce poverty through extended land ownership and agro-based industries. Prepared by PROSOC & John Miller, Inc. USA for NPC/ADB Ninth Five Year Plan 1997-2002 a 20-year perspective, Sole objective is poverty reduction, through broad based growth; social sector spending; and programs for disadvantaged groups. Emphasis on agriculture, forestry and multi-sectoral approach including environment. NPC National Conservation Strategy (NCS) 1998. To conserve natural and cultural heritage and meet basic needs, with emphasis on conserving biological diversity and maintaining essential ecosystems. Prepared by IUCN for NPC Master Plan for the Forestry Sector (MPFS) Initiated in 1999, with a 25-year perspective Sustainable use and management of forests with emphasis on protecting ecosystems, economic growth and meeting basic needs. Prepared by NPC, ADB, Finnida and Jaakko Pyroy for MOFSC3 Interim PRSP Currently being formulated Poverty reduction. Reiterates the broad priorities of the Ninth Plan, with emphasis on strengthening implementation capacity. NPC Nepal Biodiversity Action Plan (NBAP), 2003, Timeframe extends to 2012. Aims to address the objectives of the Biodiversity Convention in Nepal (for example Conservation, sustainable use and equitable benefit sharing). Proposes the development of national policies on mountain, rangeland and wetland biodiversity, and integration in key natural resource sectors. Prepared by Resources Nepal and other teams for the MOFSC 7 Identified Sustainable indicators for environment management The following chart shows the key issues for sustainable management of Nepal’s environment. Wood energy resources Mean flow utilizable surface and ground waster resources Groundwater potential Forest cover Waste water generation, collection, and treatment in urban areas Production & consumption of ozone depleting substances Use of fertilizers Threatened animal species Arable land per capita (ha/capita) Carbon dioxide emissions per capita Protected areas Deforestation rate Livestock Population Use of pesticides Total wood from forest Land use pattern Emissions of SOx, NOx, & SPM Waste disposed (t) Rate of extinction of protected species (%) Waste generation Generation of hazardous waste Generation of municipal solid waste management Land slide, flood, and other Sustainable environment management indicator for Nepal Chart prepared using smart draw trail edition 6.20, Jul, 17, 2003. 2.4 Protected areas and sustainable management The United State of America (USA) was the first to work for park management. In the 19th century USA’s park management model was used worldwide (Brandon & Wells 1992; Ghimire 1994). Establishment of parks expanded dramatically after 1950, according to Brandon & Wells 1992; McNeely, Harrison & Dingwall 1994 reported that there were approximately 25,000 protected areas in the world in 1994. Protected area coverage was estimated as 5.2 %of the Earth's land area in 1997 (Ghimire 1997). Many developing countries declared more than 10% of their land as protected areas, for example Bhutan, Nepal, Thailand, Chile, Zimbabwe and Togo (Ghimire 1994). Protected areas help save biodiversity and wildlife from being destroyed (Brandon & Wells 1992; Skonhoft 1998). However in the developing world due to poverty and population growth, protection laws have caused park-people conflicts (Heinen 1993a; Lehmkuhk 1988). The Western model of parks in many cases did not allow people to continue their traditional uses of natural resources. Higher level managers seldom understood the on8 ground issues. Wild animals often destroyed the impoverished farmer’s crops but there was no proper compensation to the farmer conflicts with between people and park management occurred (Bhandari 1994). People living close to the protected areas in the developing countries are extremely poor (Brandon & Wells 1992). They a lost their crops and some times their lives, but received nothing in return (Fiallo & Jacobson 1995; Ghai 1994; Heinen 1996; Rao et al. 2002; Sekhar 1998; Straede & Helles 2000). “A hungry peasant is an angry peasant” (Shrestha & Conway 1996). Studies shows that a restriction on use or harvesting of natural resources from the traditional lands of poor people is the main cause of park-people conflict. With “the exhaustion and restriction of natural resources, people will tend to extract as much as possible from protected areas in order to satisfy their immediate needs, without considering the benefits to be gained from longterm environmental security” (Heinen & Low 1992; Shrestha & Conway 1996). “As a result, a vicious cycle happens: the level of impoverishment in rural villages increases and further environmental deterioration occurs” (Ghimire 1994; Shrestha & Conway 1996). Due to the population pressure and poverty in developing countries, conservation strategies need to address local people’s needs (Bookbinder et al 1998; DeBoer & Baquete 1998; Ghai 1994; Infield & Namara; Ite 1996; Low & Heinen 1993; Neumann 1997). 2.5 Declaration of protected areas and sustainable management: Nepal has a relatively short history of establishment of national parks and wildlife reserves. Nepal faced various political situations under the monarchy system. Under the Rana monarchy from 1846 to 1950 Nepal was not opened to any foreigners except the British. However, some areas in the country had been set aside as hunting reserves by the Rana Regime (1846 – 1950) the concept of conservation first came into existence during the 1950s and the first wildlife law was promulgated in Nepal in 1957. Since then almost all five-year development plans have stressed the need for conserving wildlife. The Aquatic Animals Protection Act (1959) was passed in 1961, in which the importance of wetlands and aquatic animals was emphasized. The act prohibits the use of poison and explosive materials in water bodies and the destruction of dam, bridge or water system with the intent to catch or kill aquatic organisms. A small rhino sanctuary was established in Chitwan in 1964 to protect the population of one-horned rhinos (Rhinoceros unicornis) with the help of a group consisting of soldiers and trained people, and known as Gaida Gasti (Rhino patrol). Subsequently, in 1969, six Royal hunting reserves in the terai and one in the mountain area were gazetted under the Wildlife Protection Act 2015 (1969), but effective management could not be achieved because of the absence of adequate regulations, organization and staff (HMG, 1988a). In 1970, His late Majesty the King Mahendra approved in principle the establishment of the Royal Chitwan National Park and Langtang National Park. In 1973, a National Park and Wildlife Conservation (NWPC) Act came into force and a long-term project was begun with the help of the FAO & UNDP. The 1973 Act provided broad legislation for the establishment of National Parks and Reserves to protect areas and species. Since 1973, the act has undergone through its fourth amendment (HMG, 1995). 9 Four types of protected areas has been described under section 2 of the NPWC Act of 1973, namely National Park, Wildlife Reserve, Hunting Reserve and Conservation Area. These types correspond to the world conservation Union's (IUCN) international systems of protected areas categories II, IV and VI respectively. In Nepal at present 16 protected areas exist viz., 8 national parks, 4 wildlife reserves, 3 conservation areas and 1 hunting reserve covering about 16 percent of total land area of the country. The World Heritage committee of UNESCO included Royal Chitwan National Park and Sagarmatha National Park in the World Heritage Natural sites list as important habitat for endangered species of universal value and outstanding example of geological formation respectively. The Koshi Tappu Wildlife Reserve is included in the list of Wetlands of International Importance, Nepal's only Ramsar site. As of 1997, there were 13,321 different parks or equivalent reserves internationally recognized by the World Conservation Monitoring Centre (WCMC), which covered a land area of about 6,145,310 square kilometers (IUCN, 1997). National park is a protected area managed mainly for ecosystem protection and recreation. 2.5.1 Status of protected areas of Nepal Protected Areas 1 2 3 4 5 Year of Declaration 1992 1987 1997 1984 1976 Annapurna Conservation Area Dhorpatan Hunting Reserve Kanchanjunga Conservation area Khaptad National Park Koshi Tappu Wildlife Reserve (Ramsar site 1987) 6 Lantang Nation Park 1976 Lantang Buffer Zone 1997 7 Makalu Barun Nation Park 1991 Makalu Barun Buffer Zone 1998 8 Manaslu Conservation Area 1998 9 Parsa Wildlife Reserve 1984 10 Rara National Park 1976 11 Royal Chitwan National Park (WHS* 1973 1979) Royal Chitwan Buffer Zone 1996 12 Royal Bardia Nation Park 1976/88 Royal Bardia Buffer Zone 1997 13 Royal Suklaphata Wildlife Reserve 1976 14 Sagarmatha National Park (WHS* 1979) 1976 Sagarmatha Buffer Zone 2002 15 Shey Phoksundo National Park 1984 Shey Phoksundo Buffer Zone 1999 16 Shivapuri National Park 1984/2002 Total Area (sq. k.m) Land Covered by Protected areas (%) *WHS: World Heritage Site Source: DNPWC 2002a Area sq.km 7,629 1,325 2,033 225 175 Physiographic zone Middle mountain Middle mountain Middle mountain Middle hill Terai 1,710 420 1,500 830 1,663 499 106 932 High mountain High mountain High mountain High mountain High mountain Terai Siwaliks High mountain Terai Siwaliks 750 968 328 305 1,148 225 3,555 449 144 26,696 18.14% Terai Terai Siwaliks Terai Terai High mountain High mountain High mountain High mountain Middle hill 10 Ecological zones and protected areas of Nepal Source: Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation 2000. Map shows the ecological zones and protected areas of Nepal. The lowland Zone covers a narrow strip of Tarai land along the southern edge of the country. Midland is hill range, steep sided valleys. Nepal has three Main River systems Koshi, Karnali and Gandaki. 3. Sustainable Management problem: Park and people conflict Conflict issues are mainly related to people livelihood and are difficult to overcome. Protected Area management is always difficult. The problem is limited resources and population growth. Most of the protected areas were established on the public land but it also covered some of the private land. Even in the public land people used to use that land for their various purposes such as for grazing, fire wood, fodder and for timber or hunting, fishing. Once it converted to the protected area, people have no more right to use those resources. This led to the park people conflict. There is unanswered question, if any particular area was not covered under the protection what would happen? When I asked these questions to the local people related to park, they accept that we might have lost all wildlife and flora and other fauna. Park people conflict is not particular in Nepal; it can be seen in most of the developing countries. In developed world, nature of conflict is different; however, still there is conflict (Bhandari 1998). Active conservation of habitats has increased wildlife population within protected areas, which start causing damage outside the park. The relation between park-people is imbalanced when the park animals damage outside and disturb the adjacent settlement. 11 Damage of agricultural crop, human harassment, injuries and death, and livestock depredation are the common causes of this imbalanced relationship (Sharma, 1996; Jnawali, 1989; Heinen, 1993; Studsord and Wegge, 1995; Shrestha, 1994 and Kasu, 1996). The local people, who once were enjoying free access to areas henceforth covered by parks and were able to meet their needs from inside resources, now no longer, have legal access. Local people have seen the park as an attempt by the government to curtail their access to their traditional rights of resources use. However, the park has became a very good source for villagers to fulfill their resources needs through venturing into illegal poaching, logging and hunting, all of which are directly conflicting with the park's objectives (Mishra, 1982; Milton and Binney, 1980). With the establishment of the wildlife reserve, people have been denied the rights to use the resources inside the reserve and they have no rights to claim compensation for the damage to their crops by wildlife. Similarly, except in specialized area within buffer zones, the responsibility for managing resources has been taken from people who live in the vicinity and has instead been transferred to a Government agency, which is based in the distant capital. The costs of giving up access to the use of the resources fall on the rural people living in the vicinity of the reserve. In the contest of KTWR, large livestock holders continue to practice livestock grazing within the reserve, not only because of a lack of alternatives, but also due to a strong will to practice their tradition of livestock rearing and to exercise their traditional right to use the resources of Koshi Tappu. In the absence of alternatives however, such activities continue to increase despite the risks of being caught. This poses a threat not only to the existence of the wildlife reserve but also to the wetlands of the region. It is very difficult to villagers to understand why wildlife may damage their crops, while they must not kill any wild animal in return. They are not convinced of the rationale of protecting forests and wildlife, which they have been utilizing for thousands years. 3.1 Buffer Zone concept for sustainable management: Buffer zone has been defined as the area adjacent to a protected area on which land use is partially restricted to give an added layer of protection to the protected area while providing valued benefits to neighboring rural communities (Mackinnon et al. 1986). Thus, it is an area of controlled and sustainable land use, which separates the protected area from direct human pressure (Ordsol 1987; Nepal and Weber, 1993). World National Parks Conference at Bali in 1982 focused on the relationship between protected areas and human needs and stressed the relevance of integrating protected areas with other major development issues (Mishra, 1991). The message is that the protected areas should respond to the needs of local people (Sayer, 1991). The involvement of local people in the management of the protected areas for mutual benefits is widely accepted today (Oldfield, 1988). This ultimately leads to harmony and sustainability between the natural heritage and the well being of the people living on the periphery of the park 12 (Anon, 1993). These days, buffer zone concept has been widely accepted in protected area management in order to reduce conflicts between protected area authorities and the local people (Berkmuller et. al., 1990). As the park and people conflict emerged and the government realized that conservation of wildlife inside the protected areas is not productive in lack of local people's participation and also the issues that were repeatedly raised who should benefit from conservation efforts the local people or the wildlife. Through the 4th amendment in the NPWC Act of 1973 in 1992, HMG has allowed to create buffer zone surrounding national park and reserves in order to provide the use of forest products to local people. The Act defines buffer zone as "The peripheral area of the National park or reserve under section 3A for providing facilities to local inhabitants to utilize forest products regularly". The concept of buffer zones is recently developed in Nepal. The DNPWC proposed a buffer zone concept for the protected areas of Nepal in 1984. However, for the declaration of a buffer zone, the factors such as; geographical situation of the reserve, area affected from the reserve, status of settlements and appropriateness from the point of management, have to be considered. To involve local community for Sustainable management of National Parks and Wildlife Reserve, Conservation area, Buffer Zone Management plan is being implemented. There are various parks and people issues need to address. If we look the global context of sustainable management of protected area, main issues is always park people conflicts. Nepal has been implementing park people project with the help of UNDP since 1998. 3.1 Case Study of Koshi Tappu Wildlife Reserve and Management issues Koshi Tappu Wildlife Reserve (KTWR) is basically a flood plain of Sapta Koshi river system with an area of 175 sq. km and altitudinal range of 75-81 meters lies upstream of Koshi barrage across the Sunsari and Saptari districts of Koshi zone in eastern Nepal. This area was gazetted in 1976 under Section 10 of the National Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act, 1973, to preserve the habitat of the remaining population of wild water buffalo (Babalus Bubalis), which is the 26 mammal species identified as the protected wildlife species. Realizing the importance of the site, it was designated as a wetland of international importance and added to the Ramsar list on December 17, 1987. This reserve was registered under the IV category of the Commission on National Parks and Protected Areas of IUCN- the World Conservation Union. The NPWC Act, 1973, prohibits a number of activities including livestock grazing, cultivation, fishing, hunting and entry into the reserve without permission from the reserve authority. Royal Nepal Army and the Reserve staff have taken responsibilities of law enforcement. In order to address the conflicts between the park authority and the communities, the Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation has been implementing Park People Program since 1995 with UNDP assistance by adopting community based biodiversity conservation approach. 13 The main objective of the Program is to improve the socio-economic condition of the people living adjoining to the Reserve by promoting alternative energy and livelihood contributing to the conservation of biodiversity. Realizing the need of a long-term management plan, the DNPWC initiated a participatory planning exercise and developed a Management Strategy Framework in early 1998. Management Strategy Framework (based on ZOPP methodology) has identified pertinent concerns that the degradation of terrestrial habitat, degradation of aquatic habitat, inadequate local community participation for conservation, and insufficient protective measures are the direct substantial causes for impeding the effective management of the reserve (DNPWC/PPP 1998). Essential program and policy document is not prepared yet. The base issues and strategy and program for the sustainable management of Koshi Tappu Wildlife Reserve, Buffer Zone is recommended on the next chapter of this research document. Koshi Tappu is basically important due to its uniqueness and wetland. Following paragraphs will highlight the wetland related issues. 3.2 Koshi Tappu Buffer Zone and Wetlands The wetlands of the reserve and its BZ consists of rivers, streams, floodplains, oxbow lakes, river marshes, swamp forest, rice fields and seasonally flooded grasslands. important values of the wetlands of the area, it was designated as a wetland of international importance and added to the Ramsar list on 17 December 1987 (IUCN 1990b). Koshi Tappu area is the only Ramsar site in Nepal. It comprises total area of 149,000 ha. (IUCN 1998). Various inventory surveys have been carried out from various institutions such as IUCN, APEC, Woodland Mountain Institute, Ramsar convention bureau (APEC 1994). KTWR and its BZ's most wetlands are created due to the Large Dam Constructed in the Koshi River. It has upstream and down stream two way impacts to the both countries India and Nepal (Bhandari M. 2000). 4. Conclusion I examined the issues for sustainable management of protected areas of Nepal on the base of secondary sources. I found eleven major issues of sustainable management of protected areas in Nepal need to address. Poverty, and population growth is first issue which need to address for any development intervention. To manage protected areas of Nepal in sustainable way people participation ((planning stage to implementation stage) is essential and policy and strategy need to develop. Government of Nepal is still following western model of Protected Areas (PA) management. Local people are ignored in the management issues. Local people are associated with forestry, wildlife and even with the land and river systems which is under the protected area. To address this issue policy and strategy and action plan need to prepare for the conservation of local indigenous knowledge and culture. Nepal development and conservation plan has not given priority for the monitoring and evaluation. Programs have been implementing in many PAs but there are no convincing records of outcomes. Nepal has varieties of climatic and ecological zones due the variations on elevation. Nepal needs a complete bio-diversity profile and database of flora and fauna, and a separate database of each Pas. For the sustainable management of protected areas in the 14 country each needs a management plan. Nepal has declared 18% of total land for the protected area category; however, there is no links between one area to another. Special large wildlife such as elephant, tiger, rhinoceros, bleu bull, wild water buffaloes and other species large area is needed for their movement. In terms of wildlife management issues programs needs to be address regional level. Wildlife does not understand political and National geographical boundaries. Therefore varieties of corridors need to be developed and manage, with the consultation of Indian counter parts and special focus program is needed for the conservation of endangered species (Elephant, Wild Water Buffaloes, Tiger, Rhinoceros etc). Poaching is still common in Nepal specially boarder areas including Indian and Chinese. Special watchdog system needs to develop with the full participation of local people. To address the Tran boundary issues both Indian and Chinese counter parts need to contact and consider. Nepal has its own reputation about the wild flora and fauna. Each protected areas have their own uniqueness and importance. Tourism is one of the major sources of foreign exchange. There is lack of information about protected areas of Nepal and uniqueness. More publication, research is needed to explore the country’s socio-bio-physical situation. Networking is necessary with rest of world for the information flow. Within country information centers need to be developed. In the protected area, there should be an information unit. Finally, development of research centers and resources centers in the most focus sites (World Heritage sites, Ramsar sites and culturally importance sites) is also necessary to highlight the country’s uniqueness in terms of biodiversity and cultural heritage. These aforesaid points fully apply to the major study site of this study “Koshi Tappu Wildlife Reserve”. It is located in the eastern terai (175 sq. km.), was established and gazetted in 1976, primarily for the protection of the last remnant population of wild water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis arnee) and their habitat. Gharial crocodile (Gavialis gangeticus), Gangetic dolphin (Platanista gangetica), Swamp partridge (Francolinus gularis) and Bengal florican (Eupodotis benghalensis) are endangered species that inhibit the reserve. KTWR is the only Ramsar site in Nepal. In the case of sustainable management of Koshi Tappu Wildlife reserve, I examined the dependency of local people on the park using both primary and secondary data. I used non parametric statistical test to see the impact. The statistical test shows the strong impact of human and domestic animals in the Koshi Tappu Wildlife reserve. I have also presented maps to show the most impact and people dependency in the park. I also tried to find out the basic reasons of dependency on the basis of available data and using my own experiences in the area. Following are the causes of impact and dependency in the park. For the sustainable management of the park concerned stakeholders need to incorporate mentioned issues. To manage Koshi Tappu sustainable way I have recommended policy / strategy and activities and program in the recommendation section. 15 1. Poor economic condition of surrounding of Koshi Tappu Wildlife Reserve (Main cause of Dependency on the reserve). The reason is there are no alternatives available to uplift the economic situation of people. There are no programs for community Capital Generation and Mobilization. 2. Women Empowerment: Women are neglected. There is Cultural rigidity: Insufficient gender focused conservation and community development program, Illiteracy: Female literacy rate is low and Insufficient women empowerment and involvement in decision making process. 3. Very poor people (far below of poverty line): Efforts are less directed towards Special Target Group (STG) Poverty: traditional farming, and Unemployment. 4. Animal husbandry: Large number of unproductive animals (poor breed), Inadequate grazing land and grass and fodder, Inadequate veterinary facility Inadequate market for dairy product, No alternate for power on agricultural (plowing, cart pulling), Social and cultural value with local cattle (cows). 5. Crop Damage by wildlife (park people conflict): Crop damages by wild water buffaloes, wild boar, and other wildlife, Human injuries or deaths caused by wild buffaloes and wild boar, and Fencing stolen (lack of moral). 6. Fuel wood: The KTWR BZ has no sufficient forest, Local has no alternative sources of fuel wood, they are directly or indirectly depend on reserve, and nearby government forest and drift-wood from Koshi River and Trijuga River. 7. Alternatives for energy: Technology for alternative energy development is not adequately considered. 8. Forest: Lack of forest in Buffer Zone, Insufficient management intervention for improvement of the forest 9. Non-timber forest product (NTFT) (thatch material (Khar) and grass: NTFT (KharKhadai) not regularized, Instigate reserve people conflicts and Involvement of business group. 10. Eco-tourism: Eco-tourism is not adequately emphasized and Tourism related information is not sufficient, No sufficient publications are available on the Wild buffaloes and birds of Koshi Tappu wetland, And Lack of tourism infrastructure and planning. 11. Wetlands: Degradation of aquatic habitat viz. ponds, lakes canals by the invasion of weeds specially water hyacinth, Local people poison the wetlands for fishing and Over exploitation of fish and snails by local people has reduced the food availability to the birds. 16 Reference: 1. Adhikari, K. (2000) An assessment on crop damage by wild buffalo in the eastern partof Koshi Tappu Wildlife Reserve, M.Sc Thesis submitted to Central Department of Zoology, Tribhuvan University, Kathmandu 2. Anon, 1993. Report on Buffer Zone Identification in Royal Bardia National Park. Royal Bardia National Park, Thakurdwara, Nepal. 3. Baral, N. 1998. Wild Boar-Man Conflict: Assessment of Crop Damage by Wild Boar (Sus scrofa) in the South-Western Section of Royal Bardia National Park, Nepal. M.Sc. Thesis in zoology, Tribhuvan University, Nepal. 4. Bauer, J.J 1987. Recommendations for Species and Habitat Management In Koshi Tappu Wildlife Reserve after Severe Monsoonal Flooding in 1987. DNPWC/FAONEP 85/011 (Unpublished). 5. Benu, G. 1999. Park People Conflict. An Assessment of Crop Damage by Wild Animals in Proposed Buffer Zone Area of Royal Suklaphanta Wildlife Reserve, Nepal. M.Sc. Thesis in Zoology, T.U., Kathamandu. 6. Berkmuller, K., Mukherjee, S. and Mishra, B. 1990. Grazing and Cutting Pressures on Ranthambhore National Park, Rajasthan, India. Enviromental Conservation, 17 (2). 7. Bhandari, B. 1993. The Current Status of Wetlands in Nepal. In Towards Wise Use of Asian Wetlamds. Eds. H. Isozaki, M. Ando and Y. Natori. Intrenational Lake Environmental Committee Foundation, Japan. 8. Bhandari, M. 2004. A Needs Analysis for Sustainability and Environmental Management Education in Nepal, UNEP-University of Adelaide 2004 (Unpublished). 9. Bhandari M. 2000, Socio-Economic Survey of Koshi Tappu Wildlife Buffer Zone, UNDP/PPP/HMG, Nepal 10. Bhandari, M, 2000, Monitoring for Impact: A Handbook with Lessons from 13 Conservation NGOs, Christian Ottke at al, (Nepal case study part). Published by World Resources Institute, USA. 11. Bhandari, M, 1999, Roads and Agricultural development in Eastern Development Region, A Correlation analysis Jointly with Dr. K.Banskota, Bikash Sharma Published by Winrock international, (Research Report series 40) Nepal. 12. Bhandari, M, 1999, “Potential Areas for Commercialization of Agriculture in Eastern Development Region, Nepal” (A draft report submitted to Winrock International). 13. Bhandari, M, 1998, M.Sc. thesis, Assessing the impact of off road driving on the Masai Mara National Reserve and adjoining area, Kenya, submitted to International Institute for Aerospce Survey and Earth Sciences, the Netherlands. 14. Bhandari, M, 1995, Environmental Education in Nepal, A case study of Surrounding VDCs of Koshi Tappu Wildlife Reserve, report submitted to UNESCO/MAB and Ministry of Education, Nepal. 15. Bhandari, M, 1994, Study of Wetland Species Wild Water Buffalo (Bubalus Bubalis) in Koshi Tappu Wildlife Reserve, APEC-Nepal 16. Bhandari, M, 1991, Wildlife and its condition in Koshi Tappu-APEC-Nepal. 17. Biologiscgebn, B.Fureland and Forest, W. (1978), A Survey of Damaged Caused by Birds and Mammals to Cultivated Plants in Germany. 17 18. Blower, J. H. 1971. Koshi Tappu: the Home of Wild Water Buffalo (Bubalus bubalis). A Report to Ministry of Forestry, HMG, Nepal. (Unpublished) 19. CBS. 1992b. Population Data of Villages. Cintral Bureau of Statistics, National Planning Commission Secretariat, HMG, Nepal. 20. Cockrill, W . R. (ed). 1974. The Husbandry and Health of Domestic Buffalo. FAO, Rome. 21. Dahmer, T. D. 1978. Status and Distribution of the Wild Asian Buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) in Nepal. MS Thesis. University of Montana, Missoula, Montana. 22. DNPWC, 1998. National Park and Wildlife of Nepal. A Brochure Published by Department of Nartional Parks and Wildlife Conservation, Kathmandu, Nepal. 23. Dolek, M. 1987. Bird Lists for Koshi Tappu and Koshi Barrage in mid-October, 1987 (Unpublished). 24. Gable, M. 1987. Livestock Population Structure and its Physical Status. In Wildlife Conservation and Management in the Koshi Tappu Wildlife Reserve. Woodlands Resarch Nepal Program, Fall 1987, San Francisco State University, USA. (Unpublished). 25. Gordon, S. 1987. Crop Damage by Warter Buffalo in Sugar Cane Fields. In Wildlife Conservation and Management in the Koshi Tappu Wildlife Reserve. Woodlands Research Nepal Program, fall 1987, San Francisco State University, USA. (Unpublished). 26. Gupta, R.B. and H. R. Mishra. 1972. The Asiatic Wild Buffalo of Koshi Tappu: An Interim Report. Department of National Parks and Wildlife Reserve, Nepal (Unpublished). 27. Heinen, J.T. (1993), Park- People Relations in Koshi Tappu Wildlife Reserve, Nepal : A Socio-economic Analysis, Environmental Conservation 20 (1). 28. HMG Nepal, 1994. Nepal Yen Sangraha. His Majesty's Government of Nepal, Ministry of Justice, Kathmandu, Nepal. 128pp. 29. HMG Nepal, 1997. Statistical Information on Nepalsese Agriculture 1997/98. Agricultural Statistics Division, Kathmandu, Nepal. 30. HMG/UNDP. 1996. Parks and People Project (Nep/94/001): Status Report, Jan. 1995-June, 1996. Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation, HMG/UNDP, Kathmandu, Nepal. 31. Inskipp, C. 1989. Nepal's Forest Birds : Their Status and Conservation. International Council for Bird Preservation Monograph No. 4. Cambridge, England, UK. 32. IUCN 1978. Categories, Objectives and Criteria for Protected Areas. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland. 33. IUCN. 1988. Red List of Threatened Animals. The IUCN Conservation Monitoring Center. Cambridge, UK. 34. IUCN, 1997. United Nations Lists of Protected Areas. World Conservation Centre, IUCN, Gland, Switzerland. 35. Jnawali, S.R. 1989. Park - People Conflict: Assessment of Crop Damage and Human Harassment by Rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis) in Sauraha Area Adjacent to the Royal Chitwan National Park, Nepal. M. Sc. Thesis, Agricultural University of Norway. 18 36. Kasu, B.B. 1996. Status and Food Habits of Nilgai (Boselaphus tragocamelus) in Royal Bardia National Park, Nepal. M. Sc. Thesis, Agricultural University of Norway. 37. Kherwar, P.K. (1996), Endangered Environment of Wild Buffalo of Koshi Tappu with Reference to Anthropoligical Impacts. M.Sc. Thesis submitted to Central Department of Zoology, Tribhuvan University, Kirtipur Kathmandu, Nepal. 38. Kushwaha, H. L. 1986. Comparison of Census Data for Wild Buffalo and Domestic Livestock in Koshi Tappu Wildlife Reserve. (Unpublished). 39. Limbu, K.P. 1998. An Assessment of Crop Depredation and Human Harassement due to Wild Animals in Koshi Tappu Wildlife Reserve M.Sc. Thesis in Zoology, T.U., Kathmandu. 40. Mackinnons, J and K.; Child, G. and Thorsell, J. 1986. Managing Protected Areas in the Tropics. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland. 41. Mareby, J. 1987. Bird Lists for Koshi Tappu and Barrage, Early November, 1986. (Unpublished). 42. McNeely, J. A. 1984. National Park, Conservation and Development. The Role of Protected Areas in Sustaining Society. Smithsonian Institute Press, Washington D.C., USA. 43. Milton, J. P. and Binney, G.A .1980. Ecological Planning in the Nepalese Terai. A Report on Resolving Resource between Wildlife Conservation and Agricultural Land Use in Padampur Panchayat. Threshold, International Centre for Environmental Renewal, Washington, D. C., USA. 44. Mishra, H. R. 1982. Balancing Human Needs and Cin Nepal's Royal Chitwan National Park. Ambio 11 (5). 45. Mishra, H. R. 1991. Regional Review: South and South-East Asia. A Review Developed from a Regional Meeting on National Parks and Protected Areas Held in Bangkok from 1-4 Dec. 1991. IUCN, AIT and World Bank . 46. Mishra, H. R. Wemmer, C., Smith, J.L.D and Wegge, P. 1992. Bio - politics of saving Asian mammals in the Wild: Balancing Conservation in Developing Countries- A New Approach,Wegge, P. (eds), NORAGRIC Occasional Paper. Series, C. No. 11. 47. Naess, K. M. and Andersen, H. J.1993. Assessing Census Techiques for Wild Ungulates in Royal Bardia National Park, Nepal. M. Sc. Thesis, Agricultural University of Norway. 48. Nepal, S.K. and Weber, K.E. 1993. Struggle for Existence: Park - People Conflict in Royal Chitwan National Park, Nepal. Asian Institute of Technology, Bankok, Thailand. 49. Ohta, Y. and Akiba, C. 1973. Geology of the Nepal Himalayas. Himalayan Committee of Hokkaido University, Sapporo, Japan. 50. Oldfield, S. 1988. Buffer Zone Management in Tropical Moist Forest. IUCN, Tropical Forest Paper 5. 51. Orsdol, Karl G. Van. 1987. Buffer Zone Agroforestry in Tropical Forest Regions, Washington. D.C: Office of International Cooperation and USDA Forestry Service. 52. Pokharel. P. 1987. Study on the Environment of the Lesser Adjuntant Sotrk (Leptoptilos javanicus ) in Koshi Tappu Wildlife Reserve. M. Sc. Thesis submitted 19 to Central Department of Zoology, Tribhuvan University, Kirtipur Kathmandu, Nepal. 53. Pradhan, M.L., T. Bahadur K.C. and D.B. Tamang. 1967. Soil Survey of Saptari District. Report No. 12. Soil Science Section, Department of Agricultural Education and Research, Ministry of Food and Agriculture, HMG, Nepal, 54. Sah, J.P. 1993a. Wetland Vegetation and Its Management: A Case Study in Koshi Tappu Region, Nepal. M.S. Thesis, Natural Resources Program, Asian Institute of Technology, Bankok, Thailand. 55. Sayer, I. 1991. Buffer Zone Management in Rain Forest Protected Areas. Tiger Paper XVIII (4). 56. Scott, D. A. (ED). 1989. A Directory of Asian Wetlands, IUCN - the World Conservation Union, Gland, Switzerland. 57. Sharma, B.K. 1996. An Assessment of Crop Damage by Wild Animals and Depredation of the Wildlife due to Activities of Local People in Koshi Tappu Wildlife Reserve. M.Sc. Thesis submitted to Central Department of Zoology, Tribhuvan University, Kiritipur, Kathmandu Nepal. 58. Sharma, U.R. 1991. Park People Interactions in Royal Chitwan National Park, Nepal. Ph. D. Thesis. The University of Arizona, USA. 59. Sharma, U. R. 1991. Park – people interactions in Royal Chitwan National Park, Nepal. Ph.D. Dissertation. University of Arizona, Tucson, 275 pp. 60. Sharma, U. R. 2001. Cooperative management and revenue sharing in communities adjacent to Royal Chitwan National Park, Nepal. Banko Jankari 11(1): 3-8. 61. Sharma, U. R. and W. W. Shaw. 1992. Nepal's Royal Chitwan National Park and its human neighbors: A new direction in policy thinking. Paper presented at the IV World Congress on National Parks and Protected Areas, Caracas, Venezuela, 10-21 February 1992. 62. Sharma, U. R. and W. W. Wells. 1996. Nepal. Pages: 65-76 E. Lutz and J. Caldecott,eds. In: Decentralization and Biodiversity Conservation. The World Bank, Washington, D.C. 63. Shrestha, B. 1994. Studies on Park-people Conflict, Investigation on Resolving Resources Conflict between Park Conesrvation and Adjoining Settlements in the Northeastern Boundary of RCNP. M. Sc. Thesis in Zoology, Tribhuvan University, Nepal. 64. Smith, C.P. 1994. A Preliminary Report on the Status of Gangetic Dophins and other Aquatic Wildlife in Karnali, Mahakali, Narayani and Sapta Koshi Rivers. Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation, HMG, Nepal. (Unpublished). 65. Studsord, J.E. and Wegge, P. 1995. Park People Relationships: A Case Study of Damaged Caused by Park Animals around the Royal Bardia National Park, Nepal. Environment Conservation 22 (2). 66. Suwal, R.N. 1993. Koshi Tappu Wildlife Reserve: Conservation Issues and Management Measures. A Survey Report Submitted to IUCN, Nepal. 67. Upreti, B.N. 1985. The Park People Interface in Nepal Problems and New Direction; Jeffrey, A. Mc. Neely James W. Thorell and Suresh Chalise (Eds.). People and Protected Area in the Hindu Kush Himalaya, Proceeding of 20 International Workshop on the Management of National Parks and Protected Areas in the Hindu Kush-Himalaya, 6-11May 1985, Kathmandu : KMTNC and ICIMOD. 68. Upreti, B.N.1974. The Last Home of Wild Buffalo-Koshi Tappu, Nepal. Nature Conservation 28. 69. WMI/IUCN-Nepal. 1994. Biodiversity of Koshi Tappu Wildlife Reserve and its Adjacent Area. Applied Databases for Integrated Biodiversity Conservation in Nepal. Woodlands Mountain Institute / ICUN-Nepal. Consulted websites: 1. http://www.scdp.org.np/wssd/nar/NAR.pdf Retrieved on February 23, 2004 2. http://www.scdp.org.np/wssd/ Retrieved on February 23, 2004 3. Nepal COUNTRY PROFILE 2001: The World Summit for Sustainable Development (WSSD) http://www.scdp.org.np/sdan/SDANrpt1.pdf Retrieved on February 23, 2004 4. MOPE 2002, Nepal: National Assessment Report for World Summit on Sustainable Development, Ministry of Population and Environment, Nepal. http://www.scdp.org.np/sdan/SDANrpt3.pdf Retrieved on February 23, 2004 5. UNDP/ HMG 2003, Sustainable Community Development Program (Nepal Capacity 21) http://www.scdp.org.np/sdan/SDANrpt2.pdf Retrieved on February 23, 2004 6. Sharma UR, 2002, Sectoral Reports on Sustainable Development Agenda for Nepal (SDAN) on Conservation and Management of Forest, Bio-diversity Conservation in Nepal, Protected Areas of Nepal (report submitted to UNDP and Ministry of Population and Environment) http://www.scdp.org.np/sdan/SDANrpt4.pdf Retrieved on February 23, 2004 7. The Earth Charter, http://www.earthcharter.org/files/resources/Earth%20Charter%20%20Brochure%20ENG.pdf, retrieved on February 23, 2004 8. NEPAL 2002 Statement at the World Summit on Sustainable Development by Hon. Mr. Prem Lal Singh Minister for Population and Environment His Majesty's Government of Nepal http://www.un.org/events/wssd/statements/nepalE.htm, retrieved on February 23, 2004. 9. History of Sustainable Development-2002: The Road to Johannesburg http://www.wssd-smdd.gc.ca/about/history_e.cfm (Last updated: 2002-12-11), retrieved on February 23, 2004. 10. Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation 2003, www.dnpwc.gov.np retrieved on February 23, 2004. 11. Partha Dasgupta, FBA 2002 Sustainable Development: Past Hopes and Present Realizations among the World’s poor, http://www.ourplanet.com/imgversn/132/images/dasgupta.pdf, January 11, 2004. 12. United Nations Environment Program 2002, Global Environment Outlook 1, 2, 3 Earthscan Publications Ltd, London • Sterling, VA (http://www.earthscan.co.uk/asp/bookdetails.asp?key=3703) retrieved on January 11, 2004. 21 13. International Institute for Environment and Development, February 2004, http://www.iied.org/aboutiied/annrep.html#annrep2003, retrieved on January 11, 2004. 14. International Institute for Sustainable Development 2004 http://www.iisd.org | retrieved on January 11, 2004. 22