Some Evolutionary Economic History of the Oxford University Press

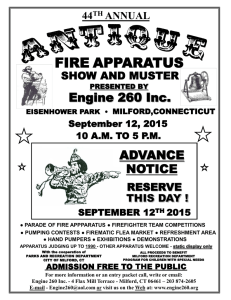

advertisement