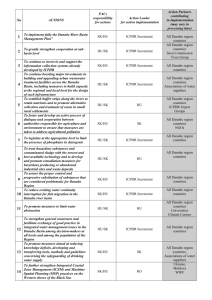

Lower Danube Green Corridor Co

advertisement

Factsheet Lower Danube Green Corridor Co-operation and management across borders and boundaries Size and location: The lower Danube flows for more than 1000 km through Romania, Bulgaria, Moldova and Ukraine. © WWF-Canon / Anton VORAUER Lower Danube Green Corridor (LDGC) comprises: 773,166 ha of existing protected areas 160,626 ha of proposed newly protected areas 223,608 ha of proposed areas to be restored to natural floodplain Floodplain: normally dry land, susceptible inundation by river water Wetland: interface between aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems Liman lake: lake formed at the mouth of a river, special term used in the Danube Delta Ecosystem Services of Floodplains and Wetlands Climate Regulation Water Supply, Regulation and Purification Nutrient cycling Sedimentation Control Food Production Raw Materials Genetic Resources Recreation and ecotourism Aesthetic Educational Cultural heritage The Lower Danube Downstream of the Iron Gates dams, the lower Danube exhibits narrow floodplains with very marked slopes on the Bulgarian side, and a large-scale floodplain up to 15 km wide on the Romanian side. Large remaining floodplain areas exist only in the confluence areas of the Romanian tributaries with the Danube. Lower Danube wetlands The Lower Danube wetlands stretch out over Serbia, Romania, Bulgaria, Moldova, and Ukraine, with a size of approximately 600,000 ha. They are a mosaic of protected areas including Ramsar sites, Biosphere Reserves, a World Heritage Site (Srebarna Lake) and National/Nature Parks (e.g. Balta Mica a Brailei). The most ecologically-important areas along the LDGC are the Bulgarian islands at Belene, the Kalimok marshes, the lower Prut floodplains and liman lakes in Moldova. Together with the Danube Delta in Romania and Ukraine, this area is one of the world’s most important ecoregions for biodiversity. Cutting off side-channels, riverbank enforcement, and constructions of dikes and drainage of wetlands for agricultural purposes have altered the dynamics of the floodplain and wetlands. Consequently, their ecological value decreased dramatically. These areas, which are now disconnected, have been lost as spawning grounds for fish, which has partially contributed to the decline of fisheries along the lower Danube. LDGC declaration On the 5th of June 2000, the Bulgarian, Romanian, Moldavian and Ukrainian Ministers of Environment signed the Lower Danube Green Corridor Declaration, recognizing the need and responsibility to protect and manage in a sustainable way one of the most outstanding biodiversity regions in the world. Page 2 of 2 The LDGC Agreement comprises the following areas: 1. Strict protection regimes. 2. Buffer zones with differentiated protection regime, in which human activities could be permitted and degraded areas restored. 3. Areas where sustainable economic activities could be developed. Why restore floodplains? Floodplains are among the most valuable ecosystems we have in Europe. An intact floodplain purifies water, recharges groundwater, provides habitats and food for plants and animals, and serves as a peaceful place for recreation. Today, around 80% of the original floodplains along the Danube have been destroyed. In Spring 2006, extreme floods ravaged the Lower Danube. Satellite images and GISmeasurements show that the Danube only took use of its former floodplains. The construction of houses, intensive agriculture industrial centres on these floodplains increases risk of severe impacts of flooding, because it removes the water retention capacity and results in floods with higher intensity and duration downstream. The restoration of floodplains means to invest in present day life and promote new solutions for the people in the region to experience prosperity and living standard improvements. Current Projects The high potential for restoration of freshwater habitats makes the LDGC the largest international wetlands protection and restoration initiative in Europe. Bulgaria Meander restoration will take place on three of the Danube’s tributaries. These model projects are the first of its type in Bulgaria. Reconnecting the river will provide opportunities for fishing, and economic benefits from grasslands and wetland resources, along with the survival of the riverine floodplain forest as an ecologic benefit. With the support of National Forestry Board, major steps for the protection and sustainable management of floodplain forest were possible: successful restoration of the natural oak forest on the Danube’s islands. Romania Dry and unproductive land in the Danube Delta has been transformed through restoration projects. It has turned into a mosaic of habitats that offer shelter and food for many species, including rare birds and valuable fish species, like pike and carp. The economic benefits of the restoration works in Babina and Cernovca (3,680 ha), in terms of increased natural resources productivity (fish, reed, grasslands) and tourism, is about €140,000 per year. Floodplains in the south of Romania will be reconnected to the Danube and land use changes will be promoted to offer a potential for sustainable tourism, natural reed harvesting, fishing and other sustainable economic activities. A pilot project to demonstrate integrated management of the floodplain forest combining nature conservation and sustainable use of natural resources will be launched on the Danube islands. Moldova With the support of the local community, a new management plan will be implemented at Lake Beleu scientific reserve. This first attempt for an integrated management of wetlands will be expanded in the Lower Prut area as part of a Trilateral Biosphere Reserve between Moldova, Romania and Ukraine. Ukraine Dikes on Tataru Island in the Danube Delta were removed, restoring natural flooding to 800 ha. Two cottages will serve as lodging for visitors who can experience the calm beauty from two newly constructed wood bridges, or from the new bird watching hides observe the unique bird population of the delta. A unique experiment with natural grazing by wild horses and cattle, to ensure development of natural forest and reed beds is ongoing. For people and nature The Lower Danube Green Corridor Agreement enables connection of people and nature, prosperity and safeguard, cultural heritage and technological progress. The first seeds for implementing and engaging for a Lower Danube Green Corridor have been sown. The Lower Danube is a dynamic system, to which tolerance of uncertainty and understanding of natural dynamics have to be developed. Narrowing the river through embankments and dikes means that human settlements can be closer to the river, but that they are also situated in high-risk flood zones. Reconnecting the floodplain to the river system and restoring its lost functions will benefit in the end both, nature and people. Further Reading: From WWF: http://www.panda.org/dcpo From the United Nations: http://whc.unesco.org/ http://www.unep-wcmc.org/ From Romania: http://www.cimec.ro/ From the Ramsar Convention: http://www.ramsar.org/ram/ram_rpt_ 53e.htm