Bathing in the Far Village: Globalization, Transnational Capital, and

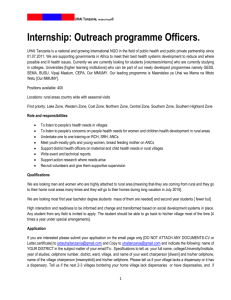

advertisement