The Revolution in Prussia

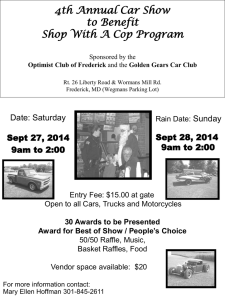

advertisement

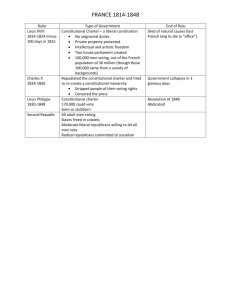

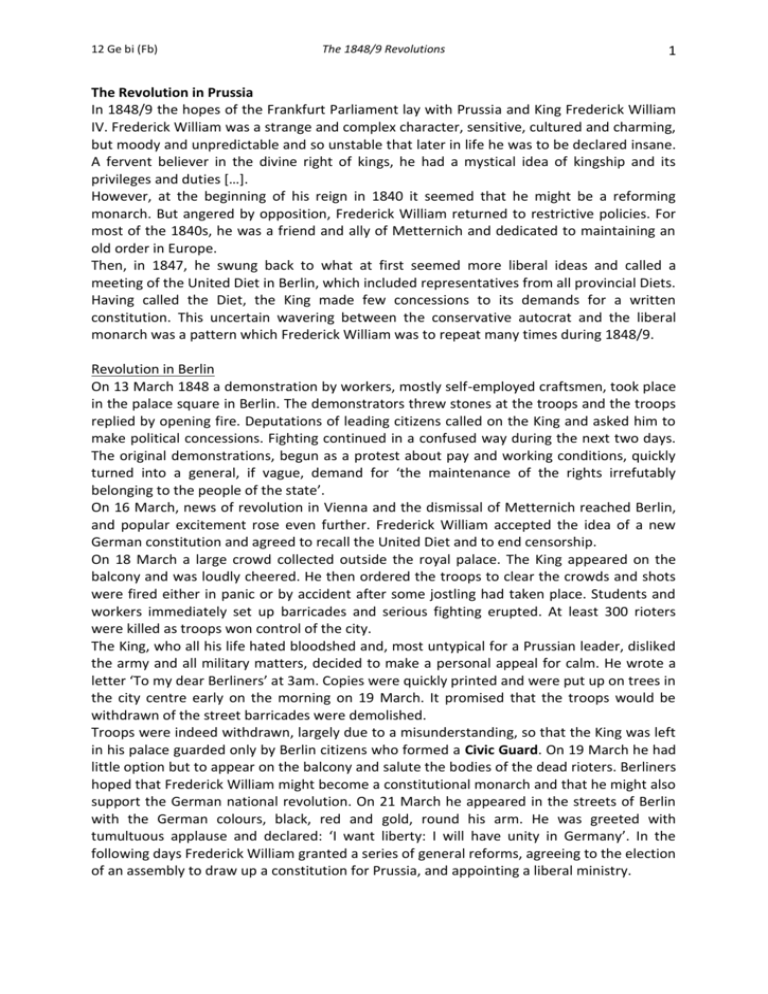

12 Ge bi (Fb) The 1848/9 Revolutions 1 The Revolution in Prussia In 1848/9 the hopes of the Frankfurt Parliament lay with Prussia and King Frederick William IV. Frederick William was a strange and complex character, sensitive, cultured and charming, but moody and unpredictable and so unstable that later in life he was to be declared insane. A fervent believer in the divine right of kings, he had a mystical idea of kingship and its privileges and duties […]. However, at the beginning of his reign in 1840 it seemed that he might be a reforming monarch. But angered by opposition, Frederick William returned to restrictive policies. For most of the 1840s, he was a friend and ally of Metternich and dedicated to maintaining an old order in Europe. Then, in 1847, he swung back to what at first seemed more liberal ideas and called a meeting of the United Diet in Berlin, which included representatives from all provincial Diets. Having called the Diet, the King made few concessions to its demands for a written constitution. This uncertain wavering between the conservative autocrat and the liberal monarch was a pattern which Frederick William was to repeat many times during 1848/9. Revolution in Berlin On 13 March 1848 a demonstration by workers, mostly self-employed craftsmen, took place in the palace square in Berlin. The demonstrators threw stones at the troops and the troops replied by opening fire. Deputations of leading citizens called on the King and asked him to make political concessions. Fighting continued in a confused way during the next two days. The original demonstrations, begun as a protest about pay and working conditions, quickly turned into a general, if vague, demand for ‘the maintenance of the rights irrefutably belonging to the people of the state’. On 16 March, news of revolution in Vienna and the dismissal of Metternich reached Berlin, and popular excitement rose even further. Frederick William accepted the idea of a new German constitution and agreed to recall the United Diet and to end censorship. On 18 March a large crowd collected outside the royal palace. The King appeared on the balcony and was loudly cheered. He then ordered the troops to clear the crowds and shots were fired either in panic or by accident after some jostling had taken place. Students and workers immediately set up barricades and serious fighting erupted. At least 300 rioters were killed as troops won control of the city. The King, who all his life hated bloodshed and, most untypical for a Prussian leader, disliked the army and all military matters, decided to make a personal appeal for calm. He wrote a letter ‘To my dear Berliners’ at 3am. Copies were quickly printed and were put up on trees in the city centre early on the morning on 19 March. It promised that the troops would be withdrawn of the street barricades were demolished. Troops were indeed withdrawn, largely due to a misunderstanding, so that the King was left in his palace guarded only by Berlin citizens who formed a Civic Guard. On 19 March he had little option but to appear on the balcony and salute the bodies of the dead rioters. Berliners hoped that Frederick William might become a constitutional monarch and that he might also support the German national revolution. On 21 March he appeared in the streets of Berlin with the German colours, black, red and gold, round his arm. He was greeted with tumultuous applause and declared: ‘I want liberty: I will have unity in Germany’. In the following days Frederick William granted a series of general reforms, agreeing to the election of an assembly to draw up a constitution for Prussia, and appointing a liberal ministry. 12 Ge bi (Fb) The 1848/9 Revolutions 2 Frederick William’s motives Did Frederick William submit to the revolution from necessity, join it out of convictions, or, by putting himself at its head, try to take it over? Given his unstable character, he may well have been carried away by the emotion of the occasion and felt, at least for a short time, that he was indeed destined to be a popular monarch. But the King’s apparent liberalism did not last long. As soon as he had escaped from Berlin and rejoined his loyal army at Potsdam, he expressed very different feelings. He spoke of humiliation at the way he had been forced to make concessions to the people and made it clear that he had no wish to be a ‘citizen’ king. However, he took no immediate revenge on Berlin and allowed decision-making for a time to pass into the hands of the new liberal ministry. The liberal ministry and the Prussian Parliament The liberal ministry was hardly revolutionary. Its members were loyal to the crown and determined to oppose social revolution. Riots and demonstrations by workers were quickly brought under control. Meanwhile the ministry, supporting German claims to the Duchies of Schleswig-Holstein, declared war on Denmark. It also supervised elections to a Prussian Parliament on the basis of manhood suffrage. The new Parliament met in May. Although it was dominated by liberals, a third of its members were radicals and there was no agreement about the nature of the new constitution. Its main achievement was to abolish the feudal privileges of the Junker class. Conservative reaction Determined to defend their interests, Prussian landowners and nobles formed local associations. In August 1848 the League for the Protection of Landed Property met in Berlin. This ‘Junker Parliament’, as it was dubbed by the radicals, pledged itself to work for the abolition of the Prussian Parliament and the dismissal of the liberal ministry. The conservatives’ main hope was the army. Most army officers were appalled at the triumph of the liberals. In Potsdam, Frederick William was surrounded by conservative advisers who urged him to win back power. The conservatives – Junkers, army officers and government officials – were not total reactionaries. Most hoped to modernise Prussia but insisted that reform should come from the King, not from the people. The tide seemed to be flowing in their favour. By the summer most Prussians seemed to have lost their ardour for revolution and for German unity. The liberal ministry was increasingly isolated. In August the King resumed control over foreign policy and concluded an armistice with the Danes, to the disgust of the Frankfurt Parliament. Riots by workers in Berlin in October ensured that the middle classes drew closer to the traditional ruling class. Habsburg success in Vienna in October also encouraged the King to put an end to the Prussian Parliament and to dismiss the liberal ministries. In November 1848 Frederick William appointed his uncle Count Brandenburg to head a new ministry. Almost at once Brandenburg ordered the Prussian Parliament out of Berlin. The Civic Guard was dissolved and thousands of troops moved into Berlin. Martial law was proclaimed. All political clubs were closed and all demonstrations forbidden. There was little resistance to the counter-revolution. The army made short work of industrial unrest in the Rhineland and Silesia. The Prussian Parliament, still unable to agree on a constitution, was dissolved by royal decree in December. Frederick William proclaimed a constitution of his own. 12 Ge bi (Fb) The 1848/9 Revolutions 3 The Prussian constitution The Prussian constitution of late 1848 was a strange mixture of liberalism and absolutism: It guaranteed the Prussians freedom of religion, of assembly and of association, and provided for an independent judiciary. There was to be a representative assembly, with two houses. The upper house would be elected by property owners, and the lower one by manhood suffrage. Voters were divided into three classes, according to the amount of taxes they paid. [ Three-Class Voting System, IF] This ensured that the rich had far more electoral power than the poor. In an emergency, the King could suspend civil rights and collect taxes without reference to Parliament. Ministers were to be appointed and dismissed by the King, and were to be responsible only to him and not to Parliament. The King could alter the written constitution at any time it suited him to do so. The King retained control of the army. The constitution thus confirmed the King’s divine right to rule whilst limit his freedom to act. A genuine parliament, albeit subservient to the crown, had been created – from above. While Frederick William would not accept that his subjects could limit his power, he was prepared to limit his own powers. The new proposals were well received in Prussia, and ministers made no secret of the fact that they hoped it would be a better model for a united Germany than the Frankfurt Parliament. They had ambitions to make Prussia the leading state in Germany, and Frederick William the leading monarch. (from: Alan Farmer & Andrina Stiles: The Unification of Germany 1815-1919 (Access to History). London (Hodder Education) 2007, pp.38-42.)