Remedies for Breach of Contract

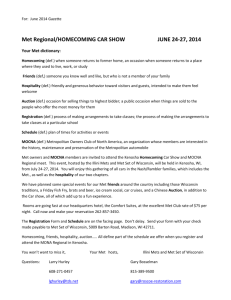

advertisement