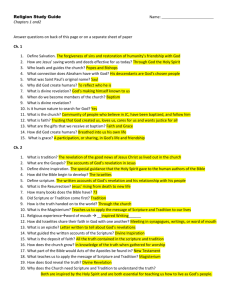

The Biblical Idea of Inspiration.

advertisement