12AP English Lit - Mister Klein`s 12AP English Homepage

advertisement

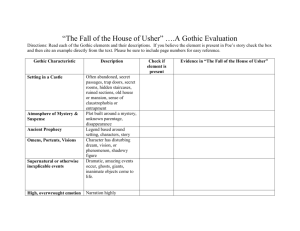

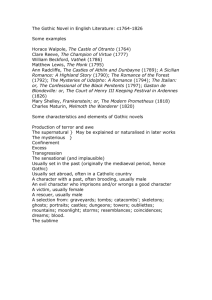

12AP English Lit. & Comp. Mr. Klein Southern Gothic Gothic literature—so called because many examples of the genre were set during the latemedieval, or Gothic, period—proliferated in England, Germany, and the United States during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Critics date its inception to 1764, when English statesman and writer Horace Walpoe published The Castle of Otranto: A Gothic Story. Set against the majestic backgrounds of mysterious castles and aging palaces, many nineteenth-century English gothic novels used such bleak landscapes to create an atmosphere of horror and suspense. In particular, gothic literature found a home with writers of the American South, who used the crumbling landscape of the antebellum era as the backdrop for their tales of fantasy and the grotesque. Major twentieth-century American authors often identified with this genre include Flannery O'Connor, Cormac McCarthy, William Faulkner, Truman Capote, and to a lesser extent, Eudora Welty. Defined by Francis Russell Hart as “fiction evocative of a sublime and picturesque landscape …depict(ing) a world in ruins,” the gothic novel presents readers with an opportunity to vicariously experience horrifying realities. By creating worlds where tragedy and repressed behaviors come to the forefront, gothic writers explore the psychology of human existence on several unique levels, notes critic Elizabeth M. Kerr. Common elements of the gothic novel include explorations of the subconscious through dreams, a good versus evil polarity in the characters, and the use of setting and atmosphere to evoke a vivid emotional response in the reader. While English Gothicism closely paralleled Romanticism in literature, frequently focusing on issues of love, sexuality, and the place of reason in human existence, Southern Gothic fiction focuses largely on themes of terror, death, and social interaction. Some commentators have argued that the adaptation of the gothic format was particularly suited to the American South because the plantation world of the antebellum period provided writers with an analogy to the medieval settings available to English gothic writers. The images of the plantation houses—representative of a quasi-feudal order in times of prosperity—contrasted with their eventual decay were evocative of the ruined castles of nineteenth-century Gothic romances, with both symbolically signaling the end of an era. However, Southern Gothic fiction also embodies immediacy and poignancy that derives from the personal and community experiences of its authors. Kerr explains this intensity as, “the cult of the past in the South, as symbolized in its ruins, its preserved glories displayed in spring pilgrimages, its monuments and graveyards, owes less to cultural climate and imagination than to remembered history.” This emphasis on history is vital to Southern Gothic fiction, which not only draws on the stylistic characteristics of nineteenth-century gothic fiction, but also finds inspiration from novels of the American past. Certain scholars—such as Leslie Fiedler in Love and Death in the American Novel (1960)—have identified specifically national concerns apparent in Southern Gothic fiction, particularly the relationships between races and genders. Other academics have been dismissive towards twentieth-century Southern Gothic novels, referring to the movement as a sub-genre of serious fiction and criticizing the works for their sometimes formulaic and sentimental storylines.