I. What is a Code of Conduct after all?

advertisement

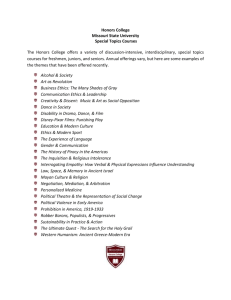

From PLI’s Course Handbook Advanced Corporate Compliance & Ethics Workshop 2008 #14681 5 THE NEXT GENERATION OF YOUR CODE OF CONDUCT: A REVISION PROCESS Joan E. Dubinsky International Monetary Fund 2 The Next Generation of Your Code of Conduct: A Revision Process Byline: Date: Submission : Joan Elise Dubinsky, Esquire August 8, 2008 PLI Advanced Corporate Compliance Seminar 2008-08-07 Most organizations already have a document that they call their Code of Conduct. It may have acquired several other names or titles. Some organizations call this a Code of Business Conduct, a Code of Ethics, a Guide for Ethical Conduct, or Standards on Ethics and Compliance. The possibilities for titles are endless. Some organizations even refer to their code by the color of its cover. Though the titles of these documents may not be standardized, one aspect of the writing process is consistent everywhere. Once a code of conduct is finally written, approved, published, and distributed, no one wants to revise it. This article examines why the revision process looks so dauntingly difficult, and suggests ways to simplify your organization’s approach. I. WHAT IS A CODE OF CONDUCT AFTER ALL? A Code of Conduct is the single most important element of your ethics and compliance program. It sets the tone and direction for the entire function. Often, the code is a stand alone document, ideally only a few pages in length. It should introduce the concept of ethics and compliance and provide an overview of what the organization means when it talks about ethical business conduct. A Code of Conduct communicates your organization’s values and principles, and summarizes the most significant rules and policies that impact organizational culture. A code has significant impact on promoting ethical behavior, reinforcing legal compliance, and enhancing corporate reputation. This small document captures “tone from the top” more effectively than any other type of communication. A Code of Conduct should be linked to the organization’s ethics and reputational risk profile. When you know the most serious and frequent kinds of ethical risks, you can begin to mitigate by discussing them in your Code. The Code should be the first resource that employees turn to when they have questions about ethics and compliance. These inquiries can be grouped into three categories: 3 Procedural questions: Who do I talk to when I want to make a report? Who can give me ethics advice that I can rely upon? Substantive questions: What are our rules on outside employment? What is our policy on retaliation? How complete must our books and records actually be? Organizational questions: What does our CEO say about ethics? Do our rules on ethics apply to everyone, including board members? The Code should also be the first resource that managers and supervisors turn to when they have concerns about ethics and compliance. Managers and supervisors will need to know: Who is accountable under our Code? What is my role as a member of management? What is expected of me and my team? Is the Code enforceable? What are the consequence if someone follows—or fails to follow— the code? Will I be informed? What are my resources? Who can help me figure out a difficult ethical question? What am I expected to know or do as a manager? If one of my employees acts unethically, what should I do next? Over the last twenty-five years, we have seen quite an evolution among codes of conduct. Some of the earliest were indistinguishable from corporate policies. The formatting was different, but the text was nearly identical. Some of the next generation attempted to summarize the major laws that applied to business operations, and then catalogued these legal summarizes alphabetically. Then, we saw codes of conduct that attempted to group laws and policies by stakeholder group or by major topic. The next—and some would argue that this is the current evolution—tried to differentiate between “rules based” and “values based” codes of conduct. Regardless of how you and your organization want to think about the internal structure and messages of your code, there are three looming philosophical questions that you should consider: Is your code normative or instrumental? Simply put, do you want a code of conduct that is enforceable upon its face, or do you want a code that is a summary of other rules and policies? A normative code can be the basis for disciplinary action, should an employee fail to comply. It will tell you what not to do. An instrumental code generally promotes your organization’s culture, and inspires employees to behave consistently with your values. Some organizations are able to find a happy medium between these two poles. How many codes should you have? There is great appeal to adopting a single, universal code of conduct that applies to: all employees, across the globe, who work for your organization all executives, leaders, and managers 4 all members of governance all partners, joint venturers, and sister organizations all third parties with whom your organization does business Yet, the expectations for conduct for each of these groups is different. If you create a code that applies universally, will it have sufficient clarity and specificity to provide the kind of guidance that individuals need? The level of detail can vary if you adopt multiple codes. Of course, multiple codes can be very difficult to enforce. And, if the task is daunting to revising just one code, your efforts grow exponentially with each successive code requiring revision. Can there be a universal code for a global company? As much as we would like to find common ground among the legal systems of our globe’s 193 nations, each sovereign nation’s laws are unique. For global companies, with operations and sales on six continents out of seven, inconsistencies among legal systems are a significant challenge. For example, many organizations are struggling with the differences in privacy laws between E.U. countries and non E.U. countries, and among E.U. countries themselves. Most organizations that offer whistleblowing systems try to describe in their codes of conduct how their hotlines or helplines operate. If, for example, your organization operates in North America, Europe, and South Africa, what should you say about the placing of anonymous calls to your hotline or helpline? Do you encourage employees, discourage employees, limit anonymity to only certain types of complaints? Or, as some companies have decided, do you issue differently worded codes of conduct for different regions of the globe? II. HOW OFTEN SHOULD YOU REVISE YOUR CODE? The simple answer, of course, is whenever necessary. In reality, many organizations strive to revise and update their codes every five years. Since Codes of Conduct are linked to legal compliance, organizational policies, and rules, it is important to keep everything synchronized. There is nothing worse than a Code that was issued ten or fifteen years earlier, that is no longer relevant because the business itself has changed radically in the interim. Organizations are never “done” the way that a loaf of bread is baked and taken from the oven. Just so with laws, rules, policies, and codes. They are always works in progress. Why is the revision process so daunting? Why do we postpone and procrastinate? Frankly, writing a code of conduct can be hard work. Rewriting that code and updating it is equally hard work. The process is time consuming. The thinking is complex. The potential for internal political battles looms large. Egos get engaged. Some of us even begin to draw lines in the sand. What make the process so hard? Several good reasons come to mind. These reasons illuminate what makes your code of conduct either extremely valuable—or easily ignored. 5 Simplicity: The laws and internal policies that guide and control a business organization’s life are complex. The number of laws and regulations continues to grow. The number of jurisdictions whose laws apply to a business’s operations continues to grow. And rarely are there sufficient efforts made to make these laws from all of these jurisdictions consistent and inter-related. We do not see many multilateral efforts to harmonize the laws and regulations that control trade, finance, commerce, competition, employment and labor, monetary policy, privacy, transparency, marketing, manufacturing, or safety. And these are the very laws and regulations that matter critically to how we run our businesses. A strong code of conduct communicates with simplicity about complexity. Writing simply takes more effort and time than almost anything else that we do. A good code follows Einstein’s adage: First thing, make everything as simple as possible. Clear Messages: Most business people are not trained as attorneys. That is probably a good thing. Most laws and regulations are written by attorneys. That is also—probably—a good thing. Legal writing is an art form, not a business imperative. Lawyers write in ways that cover all contingencies and risks—or as many as can be foreseen. Business people communicate in order to make decisions, and to make those decisions quickly despite the risks of the unknown. Great codes of conduct are written with business imperatives in mind. They cannot and should not cover all contingencies and risks. They need to help your organization’s employees recognize which laws and policies guide their decisions. They must help your employees make great decisions, quickly and effectively. They need to get to the point. Remember: a great code is not a synopsis of all of the laws that might impact your company’s operations. After all, a legalistic code can be read by lawyers. But, will it be read by the people who make your company succeed day in and day out? Consensus: Most organizations actively solicit input and feedback from employees on their policies and internal rules. Companies with active labor union involvement are intimately aware of the need to negotiate terms and conditions of employment. Companies with Works Councils are attuned to the need to consult. Even in companies with very simple labor relations, input from employees generally results in better policies and rules. Especially when a company considers adopting new rules—such as a new policy on overtime or workplace romances, a consensus approach will lead to stronger voluntary compliance. Modern workplaces are not representative democracies. Yet, there is historic truth in getting the consent of the governed. Great codes of conduct are the product of consensus. Anything that is drafted will benefit through circulation, comment, and revision. More eyes are better. The ultimate decisions on what to include in the code may not be open to debate and comment. But, how a topic is discussed and how an ethical example is expressed can and should be part of a consensus process. 6 As many of us have experienced, consensus is not perfect and it is not swift. Each iteration and each draft multiplies the time investment and the potential that some topic or concept will require additional research, exploration, or negotiation. Consensus takes time—the one commodity that most successful businesses lack. III. SO, HOW DO YOU DO IT? Here is a suggested process—with five distinct phases—that you can use and modify as you revise your Code of Conduct. Experience teaches that following these phases will result in a code of conduct that is better than good, and often quite great. We start with the assumption that your organization already has a Code of Conduct, and that the decision to revise and update the Code has been made. Let us also assume that you have adequate time and resources—or almost adequate time and resources—to complete this project. Finally, let’s assume that the impetus to modify the code is internal. In other words, your organization is not facing external legal, regulatory, law enforcement, or civil society pressure concerning your ethics and compliance program. There is one key step before you start. You must decide, as an organization, where the authority lies to both charter the code revision process and to approve the final document. In some organizations, the proverbial buck stops with the chief ethics and compliance officer. In other organizations, the chief executive officer has the final decision-making authority. In some organizations, the board of directors has the final say. There is no right place where these decisions get made. However, there are few easier ways for a revision project to go off target than not knowing whose decisions are final. Phase 1: Benchmarking and Gap Analysis This initial phase results in a clear understanding of the purpose for the code revision and an assessment of the “gaps” that need to be filled. This first phase allows you to decide what you have, what you don’t have, what you need, and what you might want. By benchmarking, you have the opportunity to compare your current code to other “model” codes or the codes of comparable organizations. This phase identifies what elements of the current code should be retained, which should be changed, which should be added, and which deleted. Benchmarking In this phase, you conduct the foundational research that helps you decide (1) what the revised Code will cover, and (2) how the Code will be used. Selecting your comparable organization is more art than science. It takes political savvyness to know against which companies to compare your code. The right group of comparables will demonstrate your current code’s strengths and weaknesses. It helps you avoid the pitfalls of others. And it allows you the freedom to make new mistakes. Usually two or three categories of comparables provide the best foundation. You may want to select companies that are in your same industry, that operate on a similar local or global platform, that generate about the same amount of revenue, that have a similar employee population size, or that 7 have a similar organizational history. Select two or three of these categories, and then find five to eight companies that fit each one. Benchmarking with 15 to 24 other organizations will provide you a wealth of ideas. Your research will also be politically and organizationally valid. There is benefit in knowing a bit about the ethics and compliance functions of each of these benchmark organizations. How the ethics office is structured and positioned can help you decide how comparable these organizations truly are to your own organization. Next, obtain copies of these organizations’ codes of conduct—however they are named. For publicly traded corporations headquartered in the United States, codes of conduct are almost always available on the Internet. For others, don’t be shy about calling, writing and asking for a copy of their code. Long gone are the days when companies treated their codes as highly proprietary documents. The most difficult step in this phase is developing the methodology for conducting your comparisons. You must decide what questions to ask and how to generate relevant comparisons before you begin your research. The following types of information can help you begin: Public Availability and Distribution A code should be made readily available to all stakeholders. What is the availability and ease of access to the Code? Style & Tone What is the style and tone of the language used in the document? Is it easy to read and reflective of its targeted audience? How compelling is the Code to read? This includes the layouts, fonts, pictures, taxonomy and structure. Presentation & Readability Commitment to Stakeholders Learning Aids/Tips Ethics Process Dispute Resolution Process Enforcement Risk Topics Does the Code identify its stakeholders? What level of compliance commitment is offered to each group? Does the Code provide any learning aids such as Q & As, checklists, examples, or case studies? Does the Code describe the role and responsibilities of the ethics and compliance office or function? Does it describe how employees can get confidential ethics advice and make reports of suspected unethical or illegal conduct? Does the Code describe the dispute resolution process, if any? Is there important contact information? Does the Code have the force of law or is it more of a guidance document for employees? Does the Code address all of the appropriate and key risk areas for the organization? Gap Analysis Once the external benchmarking is completed, the focus turns inward. Since many codes refer to an organization’s policies and rules, it will be important to collect all of those documents and review 8 them with a critical eye. This is the time to ask whether the policy function at your organization is up to date. Are there any policies that are missing or incomplete? Are there any topics about which the organization needs some rules, but just has not memorialized its informal practices? If this phase feels like you are tidying up loose policy ends, or doing routine maintenance on your policies, then you are at the right stage. It is easier to do the rule-making and policy housekeeping at this stage, rather than after you have begun to revise and rewrite your code. The end results of benchmarking is a good understanding of the current strengths and weaknesses of your current code. You will know where the code lags behind other comparable organizations. You will also know where your organization’s internal rules framework needs some work. Finally, you will have a list of ideas that you want to incorporate into the upcoming revised code. This list may include new risk areas that were not deemed critical enough for inclusion in prior code versions. It may include risk areas that are no longer of high concern. It may include features that other codes use that you believe will help your employees read and comply with the code. Finally, your list of fixes and changes will help you convince others in your organization that your code needs an overhaul. Phase 2: Design Conference As you start phase two, resist the impulse to just start writing. Instead, take a step back from the project and think about what the final product will look like. This is your chance to imagine that the revision process is complete. What does the final document say? How does it look to your readers? You may want to convene a design conference. This second phase can bring together a number of internal stakeholders who use, interpret, and enforce the code of conduct. Usually, by convening a design conference, you can reach consensus on the overall tone, voice, structure, lay-out, graphics, and key messages of the revised code. At the design conference you can discuss how to reach the right balance between behavior and values on the one hand, and compliance and rules enforcement on the other. You can consider the degree and extent to which the revised code will be used to communicate important information about your organization’s ethics process (e.g., making reports, asking questions, getting advice, cooperating and conducting internal investigations, and prohibiting retaliation) in addition to substantive guidance about specific types of compliance risk topics. Phase 3: Drafting Now, you are ready to write and rewrite. Whether the drafting is done by a single writer or a team, this is the phase where the writing gets done. At the end of this phase, you should have an approved outline, a table of contents, and a robust working draft of the code. What you write and how long it will take depends in large part on the outcome of your benchmarking and gap analysis. Be prepared for a few topics to take much longer to write than all other topics combined. Inevitably, there are a handful of topics that will require more research and discussion. 9 There is one secret that you will want to know. You don’t have to do all of the writing yourself. There is honor in hiring a professional to help you draft and redraft, revise and re-revise your code. Phase 4: Review and Approval By Phase 4, you will have a “pretty good” version of your revised code of conduct. And here, the hard work begins. The last 5 % of the effort may take 50% of the time and resources you have allocated to this project. Getting to “complete and final” will take perseverance, tact, and patience. The few topics in Phase 3 that required additional research and discussion could re-emerge as contentious. Some new topics may emerge that require you to re-think your approach. New laws and regulations could loom on the horizon, sending you and your researchers back to the library. In Phase 2, you created a set of design specfications about the ultimate “look and feel” of your code. The draft text can be put into a mock-up version of the final document. This will provide reviewers with a better sense of the lay-out of the revised code. The text of the code will make more sense if it is formatted somewhat similarly to the final product. You will want to circulate the nearly complete document to a wide group of individuals to get their feedback. This group may offer some revisions, mark unclear passages, or identify topics that somehow were not included in the draft—but need to be addressed. The more times that the revised document is circulated, the longer the process will take. Yet, each iterative review cycle results in some improvement. Eventually, though, you must decide that the drafting is done. Like a poem that is never done—only abandoned, the incremental improvements must stop. You must declare that you now have a final draft. At this point, your code is ready to be approved by the appropriate authority. Phase 5: Graphics Concept and Execution For many, the final phase is the most fun. This is when you decide what the code will look like on paper and in cyberspace. Most codes are published both in hard copy and on the web. You will need to think through how to publish your code in two different media. This includes use of graphics, photos, charts and graphs, logo’s, color, placement, and other design features so that the document is as user-friendly as possible. IV. CONCLUSION Revising a code can be a major project for any organization. The first time is generally the most difficult. Each subsequent revision cycle helps to refine the key leadership messages and themes that resonate with your organization and staff. These lasting thoughts provide continuity from version to version. Each successive “next generation” puts its own mark on your code. And it does get easier each time you revise your code. 10 11 Joan Elise Dubinsky, Esquire Ms. Dubinsky is the Chief Ethics Officer for the International Monetary Fund. In this role, she has institution-wide accountability for advising, guiding, communicating, and enforcing the Fund’s values and standards. Reporting to the Managing Director, Ms. Dubinsky provides independent ethics advice and counsel to all levels of this complex international organization. Ms. Dubinsky leads the Rosentreter Group, a management consulting practice providing expertise in business ethics, organizational development, and corporate compliance. She helps organizations implement values- and rules-based ethics initiatives, conduct program assessments, measure the effectiveness of their systems, develop executive level interventions, and design high-impact training. With close to twenty-five years of experience in the field, Ms. Dubinsky has served as the Ethics Officer, Associate General Counsel and Corporate Secretary for the American Red Cross (1985 – 1993) Senior Legal Counsel and Compliance Officer for The MITRE Corporation (1993 – 1996); founding member of the Arthur Andersen consulting practice in business ethics (1996 – 1997); and Associate Director, Employee Development for the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (1997 – 2004). Ms. Dubinsky leads the Conference Board’s Research Working Group on Working at the Intersection of Human Resources, Ethics & Compliance. She is an Executive Fellow with the Center for Business Ethics. She is a contributing author for the ECOA’s Ethics and Compliance Handbook, documenting best practices in the field of corporate compliance. She has published articles in such journals as Law Governance Review, Ethikos, Federal Ethics Reporter, IOMA’s Report on Preventing Business Fraud, CPA Consultant, and the Center for Business Ethics News. Her work in ethics training was prominently featured in Ethics Matters: How to Implement Values-Driven Management, by DawnMarie Driscoll and W. Michael Hoffman (2000). Her work on investigations is highlighted in Blackwell’s Companion to Business Ethics, ed. by Robert Fredericks (1999). A Phi Beta Kappa, Ms. Dubinsky received her Juris Doctorate from the University of Texas at Austin and her undergraduate degree in Religious Philosophy from the Residential College, University of Michigan. Ms. Dubinsky is active in the cultural arts, folk music, and dance communities of Washington, D.C., and serves on the Board of Directors of the Olney Theatre Center.