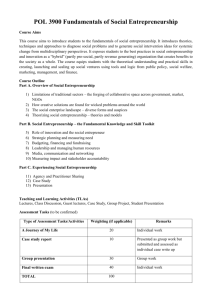

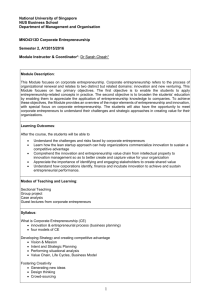

The search for corporate entrepreneurship

advertisement