Water Hyacinth Information Booklet

advertisement

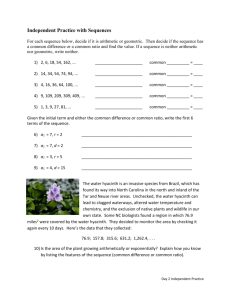

Water Hyacinth Information Booklet The Plant, Water Hyacinth Water hyacinth grows as a clonal rosette, in a whorl that grows from the centre outwards (fig. 1). Take the first fully opened leaf at the plant centre and call that leaf one. Then look for the next fully open leaf, just about opposite leaf one, which will be leaf two. Leaf three is almost opposite leaf two and behind leaf one. Count outwards from the centre in this manner labelling the leaves from one up to usually about six (but the plant can carry as many as 10 or more leaves. A new leaf is added about every six days. Stalks merging from the mother plant bearing other plants with roots, are known as daughter plants (ramets). Depending on the time of year the daughter plants can be absent or number up to six per mother plant. Water Hyacinth – Plant structure Inflorescence Leaf 2 Mother plant Leaf 3 Leaf 1 Ramet (daughter plant) Figure 1. Water hyacinth growth form. The plant also reproduces by flowering, produces spikes (inflorescences) of beautiful mauve flowers (Fig. 2), which can be produced at almost any time of the year; usually when the plant is under stress. The flowers are pollinated by generalist insect pollinators such as honey bees. When the seeds are mature the flower stalk bends under the water to deliver the seeds into the water body. The seeds germinate in response to light and particular levels of nutrient in the substrate. The germinating plantlets are tiny and usually found on newly exposed mud banks (fig. 3). Figure 2. Water hyacinth plants with (A) slender petioles (phenostage C) and (B) bulbous petioles (phenostage B). Note that the flowers are in groups called an inflorescence which is borne on a spike. From Julien et al., 1999. Figure 3. Water hyacinth seedlings The plant has very different growth forms, which depend on the stage of invasion of the water body and how much nutrient is in the water. These growth forms are known as phenostages and four forms can be recognised; from the bulbous phenostages (Fig 4), to the tall phenostages (Fig. 5). Plants that have been heavily attacked by the insect biocontrol agents are usually small to medium-sized plants, with tough spindly petioles, and curled laminas. Figure 4. Bulbous phenostage of Water hyacinth, (phenostage A). Figure 5. Mature phenostage of Water hyacinth, (phenostage C) The Water Hyacinth Weevils Lifecycle Adults Water hyacinth weevils are holometabolous insects, meaning they have a life cycle with eggs, larvae, pupae and adults. The larvae look nothing like the adults and go through complete metamorphosis during the pupal stage (Fig 6.). Two species, Neochetina eichhorniae and Neochetina bruchi, and both sexes, males and females can be easily separated (Fig. 7). The black area on the tip of the female’s nose (rostrum) extends much further towards the “face” of the beetle than it does in the male. Features which can be seen on the wing covers (elytra) of the beetle with the naked eye or a hand lens and can used to separate the two species, are given in Table 1. Figure 6. Generalised life cycle of the Neochetina weevils with approximate sizes of each life stage and where they can be most commonly found on the plant. Figure 7. Adult water hyacinth weevils. Left is Neochetina bruchi with two short markings near the centre of the wing covers (elytra) and a chevron “V” pattern across the elytra On the right is Neochetina eichhorniae which has longer markings extending further forwards on the elytra. From Julien et al 1999. Table 1. Distinguishing features of for adults of the two water hyacinth weevil species. Species N. bruchi N. eichhorniae Elytral features Markings Short Long Midway Extend forward Equal length Usually unequal length Grooves Broad Narrow Shallowly curved Strongly curved Markings Chevron “V” No chevron Obvious when emerged Fade with age Eggs Eggs are laid into the leaf surface, with a little scar on the leaf surface. Both species’ eggs look the same (Fig. 6). Eggs are laid into the leaf surface of the leaf, usually near the base of the blade (lamina) leaf number two or three, where it attaches to the petiole. Larvae are found in tunnels (“mines”) in the petioles, especially near their base (“crown”) (Figs. 6&8). Figure 8. Water hyacinth weevil larvae Collecting Weevils Adults The adults are nocturnal and generally come out to feed at night on the surface of the leaves. During the day they can be found easily, where they hide at the base of the leaf stalk, which is called the petiole. To find the adults, lift a plant out of the pond and strip away the leaves by pulling the petiole away from the crown of the plant, working from the outer leaves inwards. This type of weevil collection is quite damaging to the plants, but they will recover if you leave the crown and roots intact. If you want to collect large numbers of adult weevils without damaging the plants, sink the plants under the surface of the water of the pond, by placing a stiff grid (such as a piece of pool fence) over the top of the plants. Weigh the grid down with bricks until the bulk of the plants are underwater. Leave the pond like this for an hour or two then collect weevils from the surface of the pond with a small sieve, such as a tea strainer. Eggs Eggs are hard to find in the field, but in the classroom can be found by isolating a male and female weevil on a leaf which has been cut off the plant and placed in a petri dish or ice-cream tub. Larvae Larvae are hard to find in the early stages of development (first instar), but get easier to find as they grow into second and third (late stage) instars. They are best found by slitting the petiole lengthways with a sharp knife. Pupae Pupae are hard to find as they attach to the fine root hairs underwater, and look like a large hairy black pea (Fig. 9). Pupa Figure 9. Water hyacinth weevil pupa attached to the roots of the plant. Weevil Population Structure Weevil numbers are generally low (1-2 adults per plant), but can be increased by adding nutrients to the water, when 10-15 adults per plant may eventually appear after about eight weeks in summer. A few adults will survive winter in the base of the petioles, but most weevils overwinter as final stage (third instar) larvae. These will pupate in spring and emerge as new adults in early summer (October), and start laying eggs into the leaves. Adults can live for about 60 days, and the females will lay eggs throughout most of the year. However, in cold areas (those that commonly have frost), females stop laying eggs and their ovaries degenerate (this can be measured by careful dissection). These females may or may not restore their ovaries in spring and resume egg laying (this again can be measured by dissection). Therefore in summer, all life stages of the weevil lifecycle can be found, while in winter non-reproducing adults and late stage larvae (third instar) will be the stages found. If the number of immature individuals is greater than the number of adults, then the population can be assumed to be in a growth phase. If the opposite is found, or the adults are absent and mainly third instars are found, then the population is in decline or overwintering. Indirect Ways to measure Weevil Population Structure Adult Feeding Scars Adult feeding scars are an indirect means by which adult numbers can be estimated. The adults feed on the upper surface of the leaf blade (lamina) by removing a little square of about 2mm2 of the leaf epidermis (Fig. 10). This then turns brown in about a day and remains as a permanent record of feeding until the leaf is lost, in about six to ten weeks. Adult feeding scars are easily counted on each leaf and can interpreted as scars per leaf; scars per cm2; or scars per plant; and then related to the plant growth if the leaf turnover is accounted for. One new leaf is produced about every six days or so in summer. Figure 10. Feeding scars made by adult water hyacinth weevils. Larval Mines Larvae can be counted indirectly by recording the number of larval mines, without having to find the larva that made the mine (Fig. 11). Larval mines can be interpreted as mines per plant, and related to the age or stage of the leaf mined because one new leaf is produced about every six days or so in summer. The length of the mines can be measured to estimate larval age or duration, or as a measure of damage to the plant. A B C Figure 11. Water hyacinth weevil, larval mines. (A) early stage of larval damage. (B) late stage of damage. (C) petiole sliced open to reveal a larval mine. Examples of data, graphs tables Table one. Example of a data sheet that could used to record the number and position where water hyacinth weevils were found on water hyacinth plants. Water Hyacinth Weevil Population Structure Data Sheet Page Number…… of ..….. pages Date …………. Group Name …………..………Data Recorder……..….………... Locality……………………………………… Water quality…………………………………. Plant phenostages……………………………. Plant quality…………………………………… Plant Number …….. Site on plant where life stages were found Petiole or leaf number 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Crown Roots Number of life stages Eggs Larvae Pupae Adults Neochetina eichhorniae males females Neochetina bruchi males females Plant Number …….. Eggs Larvae Pupae Adults Neochetina eichhorniae males females Neochetina bruchi males females Plant Number …….. Eggs Larvae Pupae Adults Neochetina eichhorniae males females Neochetina bruchi males females Analysis Different data can be related to each other. Do the numbers of adult per plant relate to the number of eggs, or larval mines per plant? Learners can draw a graphs to show if these two values correlate with each other. For example the number of adult weevils collected per plant has been plotted against the level of damage recorded on each plant to explore if the two measures are related. The strong relationship shown suggests that the more weevils on the plant the more damaged the plants will be. Damage per plant (feeding scars) 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 0.0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Number of weevils per plant Figure 11. The relationship between adult water hyacinth weevil numbers and adult feeding dame on water hyacinth leaves. Bibliography Julien, M.H., Griffiths, M.W., and Wright, A.D. 1999. Biological Control of Water Hyacinth. ACIAR, Canberra, Australia. Clitheroe, F., Dempster, E., Doidge, M., Singleton, N., Mbambisa, N., van Aarde, I. 2009. Chapter 1: Local Environmental Issues. In: Focus on Life Sciences Grade 11. Learner’s Book. Maskew Miller Longman. ISBN: 978 0636 085 756