Chlorpromazine Equivalent Doses for the Newer Atypical

advertisement

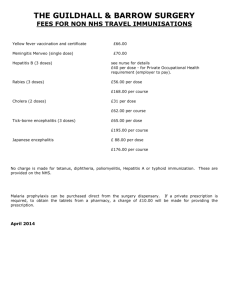

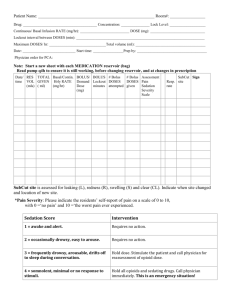

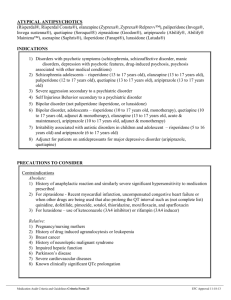

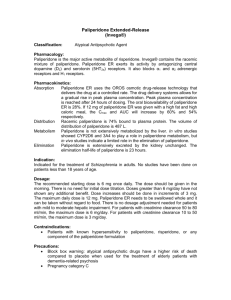

Chlorpromazine Equivalent Doses for Atypical Antipsychotics: An Update 2003-2010 Scott W. Woods, M.D.1 Posted July 29, 2011 on http://scottwilliamwoods.com. Acknowledgment: Supported by funds from the Department of Psychiatry, Yale University School of Medicine, and the Connecticut Mental Health Center, New Haven, CT, USA. 1 Department of Psychiatry, Yale University School of Medicine, and Connecticut Mental Health Center, New Haven, CT, USA. Dr. Woods may be reached at Connecticut Mental Health Center, 34 1 Park Street, New Haven, CT, USA 06519, tel 203 974-7038, fax 203 974-7057, email scott.woods@yale.edu. 2 Antipsychotic dose equivalent coefficients can be useful for various research and clinical applications. A previous paper presented a method for calculating dose equivalents and applied it to atypical antipsychotic medications approved in the US through 2002.1 This update applies the same method to identify dose equivalents for the four atypical antipsychotics approved in the US since 2003: paliperidone (2006), iloperidone (2009), asenapine (2009), and lurasidone (2010). Method. As in the previous paper, dose equivalence coefficients were derived from minimum effective doses identified in placebo-controlled fixed-dose trials for schizophrenia and/or schizoaffective disorder, defined as the lowest dose where that and higher doses were consistently significantly superior to placebo in the primary analyses. Fixed dose ranges were identified by their midpoints. Minimum effective doses were translated to chlorpromazine equivalents as previously described.1 Results. Table 1 shows the minimum effective doses identified and their corresponding chlorpromazine equivalents. Paliperidone studies 303,2,3 304,2,4 305,2,5 NCT00334126,6 and NCT003970337 featured 11 paliperidone fixed-dose arms. The 3 mg/d dose separated from placebo in study 305. Higher doses (6-15 mg/d across 10 arms) were usually effective also, the sole exception being one of three 6 mg/d arms (in schizoaffective disorder trial NCT00334126). Iloperidone studies 3000,8 3004,8 3005,8 3101,8,9 and B2028 featured 10 iloperidone fixed-dose arms. The 4 mg/d dose did not separate from placebo in either 3000 or B202. A midpoint 6 mg/d dose was effective in 3004. The 8 mg/d dose did not separate from placebo in 3 either 3000 or B202. A 12 mg/d dose was effective in 3000, with a qualification that the prespecified comparison called for the 8 and 12 mg/d arms to be merged. Higher doses (midpoint 13-24 mg/d across 4 arms) were generally effective, with the qualification that 2 arms in study 3005 separated from placebo in FDA analyses restricted to schizophrenia patients but showed only trends in prespecified analyses. Asenapine studies 041004,10,11 041021,10 and 04102310,12 featured 5 asenapine fixed-dose arms. The 10 mg/d dose was effective in 041004 and 041023, but not in 041021. The 20 mg/d dose was ineffective in 041021 and showed only a trend in 041023 in the primary analyses, although it did separate from placebo in the MMRM analysis in 041023. Lurasidone studies D1050006,13 D1050049,13 D1050196,13,14 D1050229,13 D1050231,13 and D105023315 featured 13 lurasidone fixed-dose arms. The 20 mg/d dose was investigated only in D1050049, a trial where no arm, including haloperidol 10mg/d and lurasidone 40 and 80 mg/d, separated from placebo. The 40 mg/d dose was effective in D1050006 and D1050231, but not in D1050229 or, as mentioned previously, failed study D1050049. Higher doses (80-160 mg/d across 8 arms) were usually effective, the exceptions being 120 mg/d in D1050229 and 80 mg/d in D1050049. Discussion. Since 2003, an unexplained reduced drug-placebo difference has been observed in antipsychotic development programs,16 and the number of placebo-controlled fixed-dose studies conducted per program has increased. These changes in drug development led to a change being required in the definition of minimum effective dose: specifically, the need to modify the meaning of the word “consistently” in the phrase “consistently significantly superior to placebo” from the original meaning of “almost always” to a “preponderance of the evidence” standard. With this change, identified newer drug minimum effective dose arms separated from placebo 6 4 of 9 times (67%) across program, dose arms below the identified minimum effective dose only 1 of 6 times (17%), dose arms higher than the identified minimum effective dose 17 of 24 times (71%), and active comparator arms (doses always equal to or higher than previously reported minimum effective doses1) 11 of 14 times (79%). 5 Table 1. Reported minimum effective fixed doses and chlorpromazine dose equivalents for atypical antipsychotics approved in US 2003-2010. Antipsychotic Reported Minimum Chlorpromazine 100 mg/d Medication Effective Fixed Dose Dose Equivalent Paliperidone 3 mg/d 1.5 mg/d Iloperidone 12 mg/d 6 mg/d Asenapine 10 mg/d 5 mg/d Lurasidone 40 mg/d 20 mg/d 6 1. Woods SW. Chlorpromazine equivalent doses for the newer atypical antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(6):663-7. 2. Food and Drug Administration. Invega (Paloperidone) NDA 21-999 Approval Package. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2006/021999s000_TOC.cfm. Accessed October 6, 2009. 3. Kane J, Canas F, Kramer M, et al. Treatment of schizophrenia with paliperidone extendedrelease tablets: a 6-week placebo-controlled trial. Schizophrenia research. 2007;90(13):147-61. 4. Marder SR, Kramer M, Ford L, et al. Efficacy and safety of paliperidone extended-release tablets: results of a 6-week, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62(12):1363-70. 5. Davidson M, Emsley R, Kramer M, et al. Efficacy, safety and early response of paliperidone extended-release tablets (paliperidone ER): results of a 6-week, randomized, placebocontrolled study. Schizophr Res. 2007;93(1-3):117-30. 6. Canuso CM, Dirks B, Carothers J, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of paliperidone extended-release and quetiapine in inpatients with recently exacerbated schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(6):691-701. 7. Canuso CM, Lindenmayer JP, Kosik-Gonzalez C, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebocontrolled study of 2 dose ranges of paliperidone extended-release in the treatment of subjects with schizoaffective disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(5):587-98. 8. Food and Drug Administration. Fanapt (Iloperidone) NDA 22-192 Approval Package. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2009/022192s000TOC.cfm. Accessed October 6, 2009. 9. Cutler AJ, Kalali AH, Weiden PJ, et al. Four-week, double-blind, placebo- and ziprasidonecontrolled trial of iloperidone in patients with acute exacerbations of schizophreniJ Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28(2 Suppl 1):S20-8. 10. Food and Drug Administration. Saphris (Asenapine) NDA 022117 Approval Package. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2009/022117s000TOC.cfm. Accessed October 5, 2009. 11. Potkin SG, Cohen M, Panagides J. Efficacy and tolerability of asenapine in acute schizophrenia: a placebo- and risperidone-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(10):1492-500. 12. Kane JM, Cohen M, Zhao J, et al. Efficacy and safety of asenapine in a placebo- and haloperidol-controlled trial in patients with acute exacerbation of schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;30(2):106-15. 13. Food and Drug Administration. Latuda (Lurasidone) NDA 200603 Approval Package. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2010/200603Orig1s000TOC.cfm. Accessed March 15, 2011. 14. Nakamura M, Ogasa M, Guarino J, et al. Lurasidone in the treatment of acute schizophrenia: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(6):829-36. 15. Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma. Second quarter financial results for FY 2010. http://www.dspharma.com/pdf_view.php?id=55. Accessed March 21, 2011. 7 16. Kemp AS, Schooler NR, Kalali AH, et al. What is causing the reduced drug-placebo difference in recent schizophrenia clinical trials and what can be done about it? Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(3):504-9. 8