Mental Capacity Act 2005: Practice Summary & Key Principles

advertisement

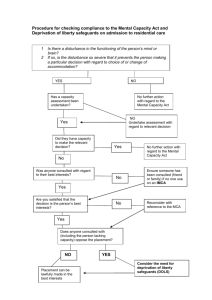

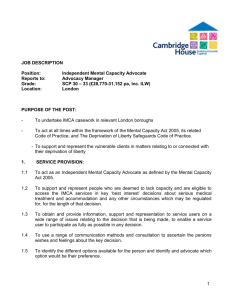

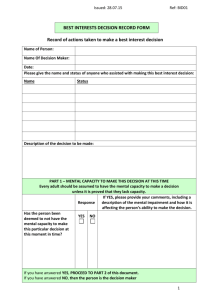

Mental Capacity Act 2005 Practice Summary When there are concerns about a person’s ability to consent to their care or treatment, practitioners need to make routine mental capacity assessments as part of their daily practice. This document is intended to provide a quick guide to this process. The Mental Capacity Act (MCA) 2005 places a duty on anyone acting in relation to a person who lacks capacity to have regard to the MCA Code of Practice. Key principles (section 1 of the MCA) The Act enshrines five key principles which must be adopted as a guide for best practice. i) You must assume that an individual has capacity unless proved otherwise. A lack of capacity has to be clearly evidenced and recorded. ii) Give all appropriate help before concluding that someone cannot make their own decision. No-one should be treated as unable to make a decision unless all practicable steps to help them have been exhausted and shown not to work. If a lack of capacity is established, it is still important that you involve the person as far as possible in making decisions. iii) Accept that individuals have the right to make decisions that appear to be either unwise or eccentric. Everyone has their own values, beliefs and preferences which may not be the same as those of other people. You cannot treat them as lacking capacity for that reason. iv) Always act in the best interests of people who do not have capacity. See below for more information on how to go about deciding what is in the best interests of the person you are providing care for. v) Decisions should be made on the basis of the least restrictive practice. Any decision taken on behalf of a person who lacks capacity must be the option that interferes least with his/her rights and freedom of action, whilst still being consistent with their best interests, This is known as ‘the least restrictive alternative’. Consent In order for a person to give *valid consent in relation to any care or treatment decisions they must: - Have capacity in relation to the particular care or treatment decision Have been given any relevant information in a way that they understand Have given consent voluntarily and free from the influence of others * Though often used, “informed consent” is primarily an American doctrine and has no standing in English law, where “valid consent” is the legally recognised term. Assessing capacity – See appendix 1 When deciding whether a person has the mental capacity to make a particular decision, you must apply a two-stage test and show that it has been applied: Stage 1: Decide whether or not there is an impairment of, or disturbance in, the functioning of the person’s mind or brain (it does not matter if this is permanent or temporary). This does not depend on having a medical diagnosis. The worker must consider the evidence and come to a conclusion. Possible outcomes: Stage 1 of the test is not met If there is no identified impairment or disturbance in the functioning of the person’s mind or brain, the individual does not lack capacity within the meaning of the Act. Stage 1 the test is met If there is impairment or disturbance, it is necessary to move on to stage two of the test below. Stage 2: Is the impairment or disturbance sufficient to make the person unable to make the particular decision? At this stage you need to focus on how the decision is made rather than the outcome of the decision. The service user will be able to make the particular decision (with appropriate help and support if necessary) if they can: understand the information relevant to that decision and retain that information (for long enough to use and weigh [see below]) and use or weigh that information as part of the process of making the decision and communicate their decision (whether by talking, using sign language or any other means). Remember to keep a good record of your decision making process, using the four bullet points above as your evidence for why someone either has or lacks capacity. Once you have determined that someone lacks capacity to make a particular decision at that time, you will need to make a decision on their behalf, which must be in their best interests and least restrictive of their basic rights and freedom. Best Interests Decisions (section 4 of the MCA) - See appendix 2 A person trying to work out the best interests of a person who lacks capacity to make a particular decision should: Encourage participation • do whatever is possible to permit and encourage the person to take part, or to improve their ability to take part, in making the decision Identify all relevant circumstances • try to identify all the things that the person who lacks capacity would take into account if they were making the decision or acting for themselves Find out the person’s views • try to find out the views of the person who lacks capacity, including: - the person’s past and present wishes and feelings – these may have been expressed verbally, in writing or through behaviour or habits. any beliefs and values (e.g. religious, cultural, moral or political) that would be likely to influence the decision in question. any other factors the person themselves would be likely to consider if they were making the decision or acting for themselves. Avoid discrimination • not make assumptions about someone’s best interests simply on the basis of the person’s age, appearance, condition or behaviour. Assess whether the person might regain capacity • consider whether the person is likely to regain capacity (e.g. after receiving medical treatment). If so, can the decision wait until then? If the decision concerns life-sustaining treatment • not be motivated in any way by a desire to bring about the person’s death. They should not make assumptions about the person’s quality of life. Consult others • if it is practical and appropriate to do so, consult other people for their views about the person’s best interests and to see if they have any information about the person’s wishes and feelings, beliefs and values. In particular, try to consult: - • • anyone previously named by the person as someone to be consulted on either the decision in question or on similar issues anyone engaged in caring for the person close relatives, friends or others who take an interest in the person’s welfare any attorney appointed under a Lasting Power of Attorney made by the person any deputy appointed by the Court of Protection to make decisions for the person. For decisions about major medical treatment or where the person should live and where there is no-one who fits into any of the above categories, an Independent Mental Capacity Advocate (IMCA) must be consulted. When consulting, remember that the person who lacks the capacity to make the decision or act for themselves still has a right to keep their affairs private – so it would not be right to share every piece of information with everyone. Avoid restricting the person’s rights • see if there are other options that may be less restrictive of the person’s rights. Take all of this into account • weigh up all of these factors in order to work out what is in the person’s best interests. Restraint (section 6 of the MCA) Any action intended to restrain a person who lacks capacity will not attract protection from liability unless the following two conditions are met: • the person taking action must reasonably believe that restraint is necessary to prevent harm to the person who lacks capacity, and • the amount or type of restraint used and the amount of time it lasts must be a proportionate response to the likelihood and seriousness of harm Under some circumstances, the prolonged use of restraint, or restraint in conjunction with other restrictive measures, might amount to a “Deprivation of Liberty”. See Appendix 3 for brief guidance on this and refer to the Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards Code of Practice for more detailed guidance. Independent Mental Capacity Advocacy (IMCA) The aim of the IMCA service is to provide independent safeguards for people who lack capacity to make certain important decisions and, at the time such decisions need to be made, have no-one else (other than paid staff) to support or represent them or be consulted. IMCAs must be independent. Instructing and consulting an IMCA • • An IMCA must be instructed, and then consulted, for people lacking capacity who have no-one else to support them (other than paid staff), whenever: - an NHS body is proposing to provide serious medical treatment, or an NHS body or local authority is proposing to arrange accommodation (or a change of accommodation) in hospital or a care home, and - the person will stay in hospital longer than 28 days, or they will stay in the care home for more than eight weeks. An IMCA may be instructed to support someone who lacks capacity to make decisions concerning: - care reviews, where no-one else is available to be consulted adult protection cases, whether or not family, friends or others are involved Ensuring an IMCA’s views are taken into consideration • The IMCA’s role is to support and represent the person who lacks capacity. Because of this, IMCAs have the right to see relevant healthcare and social care records. • Any information or reports provided by an IMCA must be taken into account as part of the process of working out whether a proposed decision is in the person’s best interests. Appendix 1 - The Assessment of Mental Capacity Appendix 2 - Making a decision for a person who lacks capacity Appendix 3 - Identifying Deprivation of Liberty The ECtHR and UK courts have determined a number of cases about deprivation of liberty. Their judgments indicate that the following factors can be relevant to identifying whether steps taken involve more than restraint and amount to a deprivation of liberty. It is important to remember that this list is not exclusive; other factors may arise in future in particular cases. • Restraint is used, including sedation, to admit a person to an institution where that person is resisting admission. • Staff exercise complete and effective control over the care and movement of a person for a significant period. • Staff exercise control over assessments, treatment, contacts and residence. • A decision has been taken by the institution that the person will not be released into the care of others, or permitted to live elsewhere, unless the staff in the institution consider it appropriate. • A request by carers for a person to be discharged to their care is refused. • The person is unable to maintain social contacts because of restrictions placed on their access to other people. • The person loses autonomy because they are under continuous supervision and control. In determining whether deprivation of liberty has occurred, or is likely to occur, decision-makers need to consider all the facts in a particular case. There is unlikely to be any simple definition that can be applied in every case, and it is probable that no single factor will, in itself, determine whether the overall set of steps being taken in relation to the relevant person amount to a deprivation of liberty. In general, the decision-maker should always consider the following: • • • • • • All the circumstances of each and every case What measures are being taken in relation to the individual? When are they required? For what period do they endure? What are the effects of any restraints or restrictions on the individual? Why are they necessary? What aim do they seek to meet? What are the views of the relevant person, their family or carers? Do any of them object to the measures? How are any restraints or restrictions implemented? Do any of the constraints on the individual’s personal freedom go beyond ‘restraint’ or ‘restriction’ to the extent that they constitute a deprivation of liberty? Are there any less restrictive options for delivering care or treatment that avoid deprivation of liberty altogether? Does the cumulative effect of all the restrictions imposed on the person amount to a deprivation of liberty, even if individually they would not? Taken from Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards Code of Practice - Chapter 2 What is Deprivation of Liberty?