rains catastrophe

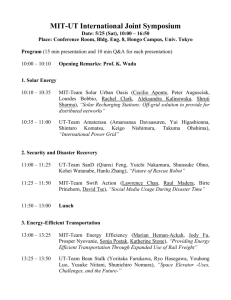

advertisement