Wave 2 (with hyperlinked data)

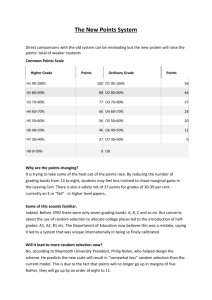

advertisement