Generalized Anxiety Disorder

Generalized Anxiety Disorder

MICHAEL F. GLIATTO, M.D.

Philadelphia Veterans Affairs Medical Center,

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

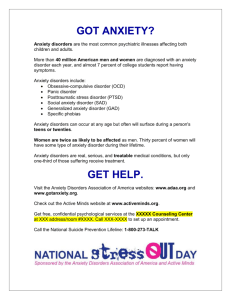

A patient information handout on generalized anxiety disorder, written by Courtenay Brooks, medical editing clerkship student at Georgetown

University School of

Medicine, Washington,

D.C., is provided on page

1602.

Patients with generalized anxiety disorder experience worry or anxiety and a number of physical and psychologic symptoms. The disorder is frequently difficult to diagnose because of the variety of presentations and the common occurrence of comorbid medical or psychiatric conditions. The lifetime prevalence is approximately 4 to 6 percent in the general population and is more common in women than in men. It is often chronic, and patients with this disorder are more likely to be seen by family physicians than by psychiatrists. Treatment consists of pharmacotherapy and various forms of psychotherapy. The benzodiazepines are used for short-term treatment, but because of the frequently chronic nature of generalized anxiety disorder, they may need to be continued for months to years.

Buspirone and antidepressants are also used for the pharmacologic management of patients with generalized anxiety disorder. Patients must receive an appropriate pharmacologic trial with dosage titrated to optimal levels as judged by the control of symptoms and the tolerance of side effects.

Psychiatric consultation should be considered for patients who do not respond to an appropriate trial of pharmacotherapy. (Am Fam Physician 2000;62:1591-600,1602.)

A nxiety disorders, such as generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), panic

See editorial on page 1492.

disorder and social phobia, are the most prevalent psychiatric disorders in the

United States, 1 and patients with these disorders are more likely to seek treatment from a primary care physician than from a psychiatrist.

2 Patients with anxiety disorders are more likely than other patients to make frequent medical appointments, to undergo extensive diagnostic testing, 3 to report their health as poor and to smoke cigarettes and abuse other substances.

4

Anxiety disorders, particularly panic disorder, occur more frequently in patients with chronic medical illnesses (e.g., hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, irritable bowel syndrome, diabetes) than in the general population.

5 Conversely, patients with anxiety disorders are more likely than others to develop a medical illness, 6,7 and the presence of an anxiety disorder may prolong the course of a medical illness.

2 Patients with anxiety disorders have higher rates of mortality from all causes.

4

TABLE 1

Diagnostic Criteria for 300.02 Generalized Anxiety Disorder

Excessive anxiety and worry (apprehensive expectation), occurring more days than not for at least six months, about a number of events or activities (such as work or school performance).

The person finds it difficult to control the worry.

The anxiety and worry are associated with three (or more) of the following six symptoms (with at least some symptoms present for more days than not for the past six months). NOTE: Only one item is required in children.

Restlessness or feeling keyed up or on edge

Being easily fatigued

Difficulty concentrating or mind going blank

Irritability

Muscle tension

Sleep disturbance (difficulty falling or staying asleep, or restless unsatisfying sleep)

The focus of the anxiety and worry is not confined to features of an Axis I disorder, e.g., the anxiety or worry is not about having a panic attack (as in Panic Disorder), being embarrassed in public (as in Social Phobia), being contaminated (as in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder), being away from home or close relatives (as in Separation Anxiety Disorder), gaining weight (as in

Anorexia Nervosa), having multiple physical complaints (as in Somatization Disorder), or having a serious illness (as in Hypochondriasis), and the anxiety and worry do not occur exclusively during

Post-traumatic Stress Disorder.

The anxiety, worry or physical symptoms cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational or other important areas of functioning.

The disturbance is not due to the direct physiological effects of a substance (e.g., a drug of abuse, a medication) or a general medical condition (e.g., hyperthyroidism) and does not occur exclusively during a Mood Disorder, a Psychotic Disorder, or a Pervasive Developmental Disorder.

Reprinted with permission from the American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association, 1994:435-6.

The definition of GAD has changed over time. Originally, little distinction was made between panic disorder and GAD. As panic disorder became better understood and specific treatments were developed, GAD was defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental

Disorders, 3d ed. (DSM-III) 8 as a disorder without panic attacks or symptoms of major depression. This definition had little reliability, 9 and current diagnostic criteria (Table 1) 10 for

GAD in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. (DSM-IV) 10 emphasize the psychic component (e.g., the worry) rather than the somatic (e.g., muscle tension) or autonomic symptoms (e.g., diaphoresis, increased arousal). In addition to the

DSM-IV framework, the symptoms of GAD can be conceptualized as being contained in three categories: excessive physiologic arousal, distorted cognitive processes and poor coping strategies.

11 The symptoms associated with each of these categories are listed in Table 2 .

10,11

Characteristics of Generalized Anxiety Disorder

TABLE 2

Symptoms and Behaviors

Associated with Generalized

Anxiety Disorder

Excessive physiologic arousal

Muscle tension

Irritability

Fatigue

Restlessness

Insomnia

Distorted cognitive processes

Poor concentration

Unrealistic assessment of problems

Worries

Poor coping strategies

Avoidance

Procrastination

Poor problem-solving skills

Information from American Psychiatric

Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed.

Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric

Association, 1994:435-6, and Gelder M.

Psychological treatment for anxiety disorders. In: the clinical management of anxiety disorders. Coryell W, Winokur G, eds. New York: Oxford University Press,

1991:10-27.

To make the diagnosis of GAD by DSM-IV 10 criteria, the worry and other associated symptoms must be present for at least six months and must adversely affect the patient's life

(e.g., the patient misses work days or cannot maintain daily responsibilities).

10 The diagnosis can be challenging because the difference between normal anxiety and GAD is not always distinct 12 and because GAD often coexists with other psychiatric disorders (e.g., major depression, dysthymia, panic disorder, substance abuse).

13

The lifetime prevalence of GAD is 4.1 to 6.6 percent, 14 which is higher than that of the other anxiety disorders. The prevalence of GAD in patients visiting physicians' offices is twice that found in the community.

15 It is more prevalent in women than in men, 1 with the median age of

onset occurring during the early 20s.

13 The onset of symptoms is usually gradual, although

GAD can be precipitated by stressful life events. The condition tends to be chronic with periods of exacerbation and remission.

13

Evaluation

The evaluation process for patients with anxiety is outlined in Figure 1.

Assessment of Patients with Anxiety

*--If some symptoms of major depression and GAD are present but do not meet the full criteria for either, treat for mixed anxiety-depressive disorder.

FIGURE 1.

Algorithm for evaluating patients with complaints of anxiety. (GAD = generalized anxiety disorder)

Initial Assessment

After obtaining a patient history, the physician should try to categorize the anxiety as acute

(or brief or intermittent) or persistent (or chronic).

15,16 Acute anxiety lasts from hours to weeks

(in contrast, panic attacks last for minutes) and is usually preceded by a stressor. Often, comorbid conditions (e.g., major depression) are not present.

15 Persistent anxiety lasts for months to years and can include what is called "trait anxiety." Trait anxiety can be viewed as part of a patient's temperament; for instance, a patient may say, "I've always been nervous, but

I don't know about what."

Generalized anxiety disorder is distinguished from other medical and psychiatric conditions and normal worrying principally by the long duration of the anxiety and the resultant impairment in daily functioning.

Although there is usually not a precipitating stressor in most cases of persistent anxiety, a stressor can exacerbate the patient's baseline level of anxiety. This situation is called "double anxiety" (i.e., acute anxiety superimposed on persistent anxiety).

15 GAD is a form of persistent anxiety and can occur in patients with or without trait anxiety.

Patients with GAD present with a wide variety of symptoms and range of severity.

12 Some patients may emphasize a special symptom (e.g., insomnia) and not report other symptoms that are usually associated with GAD.

12 Some patients may not complain of anxiety or specific worries but present with exclusively somatic symptoms such as diarrhea, palpitations, dyspnea, abdominal pain, headache or chest pain.

2 These patients warrant a full medical evaluation because there may be no indication that GAD is the etiology. Conversely, physicians should include a psychiatric disorder in the differential diagnosis when symptoms are vaguely described, do not conform to known pathophysiologic mechanisms, persist after a negative work-up and are not resolved by reassurance. Patients with this clinical profile should be asked as early in the evaluation as possible about worries, "nerves," or anxiety, acute or chronic stressors, and about the presence of symptoms listed in Tables 1 10 and 2.

10,11

Evaluation for Medical Disorders

Nonpsychiatric disorders must be ruled out before GAD can be diagnosed as the etiology of a patient's complaint of anxiety. Neurologic and endocrine diseases, such as hyperthyroidism and Cushing's disease, are the most frequently cited medical causes of anxiety.

17 Other medical conditions commonly associated with anxiety include mitral valve prolapse, carcinoid syndrome and pheochromocytoma.

17 It must be stressed that these conditions, although often cited, are clinically uncommon, and all patients who present with the complaint of anxiety do not require an extensive work-up to exclude these other medical conditions. Medications such as steroids, over-the-counter sympathomimetics, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

(SSRIs), digoxin, thyroxine and theophylline may cause anxiety.

17 The physician should also inquire about the use of herbal products or vitamins. If possible, all exogenous substances should be removed before initiating treatment of patients with GAD.

Evaluation for Substance Abuse

Use of and withdrawal from addictive substances can cause anxiety. The physician should inquire about the patient's use of alcohol, caffeine, nicotine and other commonly used substances (including those given by prescription). Corroborative history from family members may be necessary.

17

Evaluation for Other Psychiatric Disorders

The evaluation for other psychiatric disorders is probably the most challenging aspect of patient evaluation because the symptoms of GAD overlap with those of other psychiatric disorders (e.g., major depression, substance abuse, panic disorder) and because these disorders often occur concomitantly with GAD. Generally, GAD should be considered a diagnosis of exclusion after other psychiatric disorders have been ruled out. Because of the overlap and comorbidity associated with other psychiatric disorders, some authors have questioned whether GAD is a distinct entity and have posited that it is a variant of panic disorder or major depression.

18,19

TABLE 3

Distinguishing Characteristics of Generalized Anxiety Disorder, Panic

Disorder and Major Depression

Disorder

Generalized anxiety disorder

Panic disorder

Major depression

Distinguishing feature

Worry about a specific concern

Age of onset

Associated symptoms

Early 20s Restlessness, motor tension, fatigue

Intense, brief, acute anxiety; frequency of attacks variable; often no precipitant

Bimodal onset

(late adolescence, mid-30s)

Persistently low mood; may be accompanied by persistent anxiety

Mid-20s

Rapid heart rate, trembling, diaphoresis, dyspnea

Neurovegetative symptoms (e.g., insomnia, lack of appetite, guilt)

Course of illness

Family history

Chronic Generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, alcohol abuse

Variable periods of remissions and relapses

Symptoms remit but may recur

Panic disorder, major depression, alcohol abuse

Major depression, alcohol abuse

Information from American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders.

4th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association, 1994:436, and Noyes R, Woodman C, Garvey

MJ, Cook BL, Suelzer M, Clancy J, et al. Generalized anxiety disorder vs. panic disorder. Distinguishing characteristics and patterns of comorbidity. J Nerv Ment Dis 1992;180:369-79.

Symptoms of GAD can occur before, during or after the onset of the symptoms of major depression or panic disorder.

12 Some patients have symptoms of anxiety and depression but do not meet the full criteria as delineated in DSM-IV, 10 for GAD, panic disorder or major depression. In these cases, the term "mixed anxiety-depressive disorder" can be applied, although it is not yet part of the official nosology. Despite the confusion, anxious patients should be asked about the symptoms of panic attacks and the neurovegetative symptoms

(including suicidal ideation) that are associated with major depression. When more than one psychiatric condition exists, an attempt should be made to determine which disorder occurred first. Some distinguishing characteristics of GAD, panic disorder and major depression are listed in Table 3 .

10,19

Obsessive-compulsive disorder and social phobia should also be considered in the evaluation for comorbid disorders. The key symptom of obsessive-compulsive disorder is recurring, intrusive thoughts or actions. Social phobia is characterized by intense anxiety provoked by social or performance situations.

10 Because patients with GAD may present with mostly somatic complaints, somatization disorder is also a consideration. The distinguishing feature of this disorder is chronic, multiple physical complaints that involve several organ systems.

Patients with exclusively GAD have a much more limited range of physical complaints.

Treatment

Psychologic Treatments

Nonpharmacologic modalities should be the initial treatment for patients with mild anxiety 4 to address the three categories of symptoms of GAD (Table 2) .

10,11 Relaxation techniques and biofeedback are used to decrease arousal.

11 Cognitive therapy helps patients to limit cognitive distortions by viewing their worries more realistically, enabling them to make better plans to manage their anxiety. In cognitive therapy, patients may be taught to record their worries, listing evidence that justifies or contradicts the extent of their concerns.

20 Patients also learn that "worrying about worry" maintains anxiety and that avoidance and procrastination are not effective ways to solve problems.

20

Patients with generalized anxiety disorder may respond to psychologic or pharmacologic therapies or a combination of both approaches.

A small number of studies have found that cognitive therapy is more effective than behavior therapy 21 , psychodynamic psychotherapy 22 and pharmacotherapy, 23,24 but more research needs to be conducted before the superiority of cognitive therapy is firmly established.

20 Patients with personality disorders, those with chronic social stressors and those who expect little benefit from psychologic treatments do not respond well to psychotherapeutic techniques for the treatment of anxiety.

25 Often, psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy are necessary.

Family members should participate in the treatment plan of patients with GAD. Initially they can provide additional historical information and contribute to the formulation of the treatment plan. Because patients with this disorder tend to be vigilant for signs of danger and may misinterpret information, 26 family members can provide another perspective on the patient's problems. In addition, family members should be included in efforts to help the patient develop problem-solving skills and can also help decrease the social isolation of patients with GAD by providing structured activities to promote interaction with others and lessen rumination about problems. Another source of structured activity includes day programs provided by community mental health centers. If substance abuse is prominent, the patient should be referred to a rehabilitation facility. Patients and their families can be referred to the Anxiety Disorders Association of America (301-231-9350) for further information about available resources.

Pharmacologic Treatment

Pharmacologic therapy should be considered for patients whose anxiety results in significant impairment in daily functioning. Study results have not revealed an optimal duration of pharmacologic treatment for patients with GAD.

27 While 25 percent of patients relapse within one month of discontinuing drug therapy and 60 to 80 percent relapse within one year, 16 patients treated for at least six months have a lower relapse rate than those treated for shorter time periods.

16

TABLE 4

Benzodiazepines Commonly Prescribed for Anxiety Disorders

Name

Half-life

(hours)

Alprazolam (Xanax) 14

Chlordiazepoxide

(Librium)

20

Clonazepam

(Klonopin)

50

Clorazepate

(Tranxene)

60

Diazepam (Valium) 40

Lorazepam (Ativan) 14

Oxazepam (Serax) 9

Dosage range

(per day)*

1 to 4 mg

15 to 40 mg

0.5 to 4.0 mg

15 to 60 mg

6 to 40 mg

1 to 6 mg

30 to 90 mg

Initial dosage

0.25 to 0.5 mg four times daily

15 to 30 mg three times daily

Weekly cost†

$15 to 19

5 to 10 mg three times daily

2

0.5 to 1.0 mg twice daily

10 to 12

7.5 to 15.0 mg twice daily

0.5 to 1.0 mg three times daily

18 to 25

2 to 5 mg three times daily

1 to 2

13 to 17

15 to 21

*--For elderly patients, use one half of the dosage listed.

†--Estimated cost to the pharmacist based on average wholesale prices in Red Book. Montvale, N.J.:

Medical Economics Data, 1999. Cost to the patient will be higher, depending on prescription filling fee.

Information from Hoehn-Saire R, McLeod DR. Clinical management of generalized anxiety disorder. In: the clinical management of anxiety disorders. Coryell W, Winokur G, eds. New York: Oxford University Press,

1991:79-100, and Schatzberg AF, Cole JO, DeBattista C. Manual of clinical psychopharmacology. 3rd ed.

Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Press Inc., 1997.

Benzodiazepines.

The anxiolytics most frequently used are the benzodiazepines 4 (Table 4) .

12,28

All of the benzodiazepines are of equal efficacy 29 and all act on the g-aminobutyric acid

(GABA)/benzodiazepine (BZ) receptor complex, causing sedation, problems in concentrating and anterograde amnesia.

4 Benzodiazepines do not decrease worrying per se, but act to lower anxiety by decreasing vigilance and by eliminating somatic symptoms such as muscle tension.

Tolerance to the sedation, impaired concentration and amnesia effects of these drugs develop within several weeks, 27 although tolerance to the anxiolytic effects occurs much more slowly-if at all.

4 Benzodiazepine therapy can begin with 2 mg of diazepam, or its equivalent, three times daily. The dosage can be increased by 2 mg per day every two to three days until the symptoms abate, side effects develop 4 or a daily dose of 40 mg is reached.

28 Diazepam does not have to be used as the initial agent; several alternatives are available. In the elderly patient, benzodiazepine therapy should begin at the lowest possible dosage and increased slowly.

30

Agents with short half-lives, such as oxazepam (Serax), are easily metabolized and do not cause excessive sedation. These agents should be used in the elderly and in patients with liver disease. They are also suitable for use on an "as-needed" basis. Agents with long half-lives, such as clonazepam (Klonopin), should be used in younger patients who do not have concomitant medical problems. In addition to improved compliance, the longer acting agents offer several advantages: they can be taken less frequently during the day, patients are less likely to experience anxiety between doses and withdrawal symptoms are less severe when the medication is discontinued. When a benzodiazepine is prescribed, the patient should be warned about driving and operating heavy machinery while taking this medication.

Use of benzodiazepines in therapeutic dosages does not lead to abuse, and addiction is rare.

12

The benzodiazepines most likely to be abused are those that are rapidly absorbed such as diazepam, lorazepam (Ativan) and alprazolam (Xanax).

27 Alprazolam should be prescribed only for patients with panic disorder. When abused, benzodiazepines are usually abused with other substances, particularly opiates.

31 The patients most likely to abuse benzodiazepines are those who have a previous history of alcohol or drug abuse, and those with a personality disorder.

28

All benzodiazepine therapy can lead to dependence; that is, withdrawal symptoms occur once the medications are discontinued. Withdrawal symptoms include anxiety, irritability and insomnia, and it can be difficult to differentiate between withdrawal symptoms and the recurrence of anxiety. Seizures occur rarely during withdrawal.

28 Withdrawal symptoms tend to be more severe with higher dosages, with agents that have short half-lives, with rapidly tapered dosages, and in patients with current tobacco use or with a history of illegal drug use.

15 The risk of dependence increases as the dosage and the duration of treatment increases, but it can occur even when appropriate dosages are used continuously for three months.

4,27

Withdrawal symptoms begin six to 12 hours after the last dose of an agent with a short halflife and 24 to 48 hours after the last dose of an agent with a longer half-life.

27 In patients who have taken a benzodiazepine for more than six weeks, the dosage should be decreased by 25 percent or less per week to prevent withdrawal symptoms.

4 Patients may experience rebound anxiety (akin to the rebound hypertension that occurs when some antihypertensives are discontinued) once the tapering process is completed, but this is transient and ends within 48 to 72 hours.

28 Once the rebound anxiety ends, a patient may re-experience the original symptoms of anxiety, referred to as recurrent anxiety.

Although few controlled studies support the long-term use of benzodiazepines, GAD is a chronic disorder, and some patients will require benzodiazepine therapy for months to years.

9

Generally, patients who present with acute anxiety or those with chronic anxiety who undergo a new stressor ("double anxiety") should receive benzodiazepine therapy for several weeks.

13

Patients may be less tolerant of anxiety that recurs when the benzodiazepine is discontinued 12 and, if necessary, it may have to be resumed indefinitely. Patients who use benzodiazepines chronically tend to be elderly, to be in psychologic distress and to have multiple medical problems.

30

Benzodiazepines remain the most widely used pharmacologic agents for the treatment of patients with generalized anxiety disorder, but buspirone is commonly used as a treatment modality.

Other Medications.

Buspirone (BuSpar) is the drug often used in patients with chronic anxiety and those who relapse after a course of benzodiazepine therapy.

13 It is also the initial treatment for anxious patients with a previous history of substance abuse.

13 Buspirone appears to be as effective as the benzodiazepines in the treatment of patients with GAD, 32 and its use does not result in physical dependence or tolerance.

15

Unlike the immediate relief of symptoms that occurs with benzodiazepine therapy, buspirone's onset of action takes two to three weeks.

31 Therefore, patients should be informed of the expected delay in relief of symptoms. Buspirone has an opposite effect of the benzodiazepines in that it treats the worry associated with GAD rather than the somatic symptoms.

31 However, buspirone may not be as effective in patients who have been treated with a benzodiazepine during the previous 30 days.

13

The initial dosage of buspirone is 5 mg three times daily with a gradual dose titration until symptoms remit or the maximum dosage of 20 mg three times daily is reached.

15 If the dosage is titrated too quickly, headaches or dizziness may occur.

15 In patients who are taking benzodiazepines at the time of the initiation of buspirone, tapering the benzodiazepine should not begin until the patient reaches a daily dosage of 20 to 40 mg of buspirone.

15

In addition to the GABA/BZ complex, research has shown that GAD involves several neurotransmitter systems, including that of norepinephrine and serotonin.

9 Pharmacologic agents that affect these neurotransmitters, such as the tricyclic antidepressants and the SSRIs,

have been studied in patients with GAD who do not respond to the benzodiazepine therapy or buspirone.

Imipramine (Tofranil) has been shown to be effective in controlling the worrying that is associated with GAD, 33 but whether it is as effective as benzodiazepines or buspirone in those patients who have anxiety without depressive symptoms has not been determined.

15

Imipramine also has anticholinergic and antiadrenergic side effects that limit its use.

Desipramine (Norpramin) and nortriptyline (Pamelor) can be used as alternatives.

Trazodone (Desyrel) is a serotonergic agent, but because of its side effects (sedation and, in men, priapism), it is not an ideal first-line agent.

9 Daily dosages of 200 to 400 mg are reported to be helpful in patients who have not responded to other agents.

9 Nefazodone (Serzone) has a similar pharmacologic profile to trazodone, but it is better tolerated and is a good alternative.

9,31 Paroxetine (Paxil), an SSRI, has also been studied as a treatment for patients with GAD, 34 but the trial was small, as has been the case with most of the antidepressants under investigation. Venlafaxine SR (Effexor) is the first medication to be labeled by the U.S.

Food and Drug Administration as an anxiolytic and as an antidepressant; thus, it can be used for the treatment of patients with major depression or GAD, or when they occur comorbidly.

35

Antihistamines are not potent anxiolytics. Although some antipsychotic drugs have sedating properties, they should rarely be used as therapy for patients with GAD.

12 Beta-adrenergic agents are useful for the treatment of patients with performance anxiety (a type of social phobia) because they lower heart rate and decrease tremulousness; they do not however, decrease the worrying or other somatic symptoms associated with GAD.

12

Two herbal remedies that are often used for the treatment of anxiety are Valeriana officinalis

(valerian), a root extract, and a beverage made from the root of Piper methysticum (kavakava). Both have sedating properties, but kava has worrisome side effects that include synergy with alcohol and benzodiazepines, 36 dyskinesias and dystonia, 37 and dermopathy.

38 Valerian root has been reported to cause delirium and cardiac failure if abruptly discontinued.

39 Further studies are needed before these herbal products can be recommended as therapeutic agents for persons with GAD.

Consultation with a psychiatrist should be considered if a patient with GAD does not respond to an appropriate course of benzodiazepine or buspirone therapy. A psychiatrist can help clarify the diagnosis, determine if a comorbid psychiatric disorder is present and determine which comorbid disorder should be treated as the primary disorder. A psychiatrist can also make recommendations about therapy, including the addition of psychotherapy and changes in medications.

This article exemplifies the AAFP 2000 Annual Clinical Focus on mental health.

The Author

MICHAEL F. GLIATTO, M.D., is currently an attending psychiatrist in the Department of Psychiatry at the Philadelphia

Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Philadelphia, and a clinical assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia. He received a medical

degree from the St. Louis University School of Medicine and completed a residency in internal medicine at Hahnemann University Hospital, Philadelphia, and a residency in psychiatry at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Address correspondence to Michael F. Gliatto, M.D., Department of Psychiatry, Philadelphia Veterans

Affairs Medical Center, 38th and Woodland Ave., Philadelphia, PA 19104. (e-mail:

Gliatto.Michael_Ft@Philadelphia.VA.Gov

) Reprints are not available from the author.

REFERENCES

1.

Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the National

Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994;51: 8-19.

2.

Shear MK, Schulberg HC. Anxiety disorders in primary care. Bull Menninger Clin 1995;59:A73-85.

3.

Katon WJ, Von Korff M, Lin E. Panic disorder: relationship to high medical utilization. Am J Med

1992;92:7S-11S.

4.

Shader RI, Greenblatt DJ. Use of benzodiazepines in anxiety disorders. N Engl J Med 1993;328:1398-

405.

5.

Wells KB, Golding JM, Burnam MA. Psychiatric disorder in a sample of the general population with and without chronic medical conditions. Am J Psychiatry 1988;145:976-81.

6.

Rogers MP, White K, Warshaw MG, Yonkers KA, Rodriguez-Villa F, Chang G, et al. Prevalence of medical illness in patients with anxiety disorders. Int J Psychiatry Med 1994;24:83-96.

7.

Wells KB, Golding JM, Burnam MA. Chronic medical conditions in a sample of the general population with anxiety, affective, and substance use disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1989;146:1440-6.

8.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 3d.

Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association, 1980:232-3.

9.

Connor KM, Davidson JR. Generalized anxiety disorder: neurobiological and pharmacotherapeutic perspectives. Biol Psychiatry 1998;44:1286-94.

10.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed.

Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association, 1994:435-6.

11.

Gelder M. Psychological treatment for anxiety disorders. In: the clinical management of anxiety disorders. Coryell W, Winokur G, eds. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991:10-27.

12.

Hoehn-Saire R, McLeod DR. Clinical management of generalized anxiety disorder. In: the clinical management of anxiety disorders. Coryell W, Winokur G, eds. New York: Oxford University Press,

1991: 79-100.

13.

Rickels K, Schweizer E. The clinical course and long-term management of generalized anxiety disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1990;10:101S-10S.

14.

Robins LN, Regier DA. Psychiatric disorders in America: the epidemiologic catchment area study.

Robins LN, Regier DA, eds; with a foreword by Freedman DX. New York: Free Press, 1991.

15.

Schweizer E, Rickels K. Strategies for treatment of generalized anxiety in the primary care setting. J

Clin Psychiatry 1997;58(suppl 3):27-33.

16.

Hales RE, Hilty DA, Wise MG. A treatment algorithm for the management of anxiety in primary care practice. J Clin Psychiatry 1997;58(suppl 3): 76-80.

17.

Wise MG, Griffies WS. A combined treatment approach to anxiety in the medically ill. J Clin

Psychiatry 1995;56(suppl 2):14-9.

18.

Liebowitz MR, Hollander E, Schneier F, Campeas R, Fallon B, Welkowitz L, et al. Anxiety and depression: discrete diagnostic entities? J Clin Psychopharmacol 1990;10:61S-6S.

19.

Noyes R, Woodman C, Garvey MJ, Cook BL, Suelzer M, Clancy J, et al. Generalized anxiety disorder vs. panic disorder. Distinguishing characteristics and patterns of comorbidity. J Nerv Ment Dis

1992;180:369-79.

20.

Clark DM, Phil D, Wells A. Cognitive therapy for anxiety disorders. In: Dickstein LJ, Riba MB,

Oldham JM, eds. Cognitive therapy. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Press, Inc., 1997.

21.

Butler G, Fennell M, Robson P, Gelder M. Comparison of behavior therapy and cognitive behavior therapy in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol 1991;59:167-75.

22.

Durham RC, Murphy T, Allan T, Richard K, Treliving LR, Fenton GW. Cognitive therapy, analytic psychotherapy and anxiety management training for generalised anxiety disorder. Br J Psychiatry 1994;

165:315-23.

23.

Power KG, Jerrom DW, Simpson RJ, Mitchell MJ. A controlled comparison of cognitive-behaviour therapy, diazepam and placebo in the management of generalised anxiety. Behav Psychother 1989;17:1-

14.

24.

Power KG, Simpson RJ, Swanson V, Wallace LA, et al. A controlled comparison of cognitive-behavior therapy, diazepam, and placebo, alone and in combination, for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. J Anxiety Disord 1990;4:267-92.

25.

Durham RC, Allan T. Psychological treatment of generalised anxiety disorder. A review of the clinical significance of results in outcome studies since 1980. Br J Psychiatry 1993;163:19-26.

26.

Mathews A. Why worry? The cognitive function of anxiety. Behav Res Ther 1990;28:455-68.

27.

Schweizer E. Generalized anxiety disorder. Longitudinal course and pharmacologic treatment. Psychiatr

Clin North Am 1995;18:843-57.

28.

Schatzberg AF, Cole JO, DeBattista C. Manual of clinical psychopharmacology. 3d ed. Washington,

D.C.: American Psychiatric Press Inc., 1997.

29.

Thompson, PM. Generalized anxiety disorder treatment algorithm. Psychiatric Annals 1996;26:227-32.

30.

Shorr RI, Robin DW. Rational use of benzodiazepines in the elderly. Drugs Aging 1994;4:9-20.

31.

Longo LP. Non-benzodiazepine pharmacotherapy of anxiety and panic in substance abusing patients.

Psychiatr Annals 1998;28:142-53.

32.

Goa KL, Ward A. Buspirone. A preliminary review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic efficacy as an anxiolytic. Drugs 1986;32:114-29.

33.

Rickels K, Downing R, Schweizer E, Hassman H. Antidepressants for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. A placebo-controlled comparison of imipramine, trazodone, and diazepam. Arch Gen

Psychiatry 1993;50:884-95.

34.

Rocca P, Fonzo V, Scotta M, Zanalda E, Ravizza L. Paroxetine efficacy in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1997;95: 444-50.

35.

Aguiar LM, Haskins T, Rudolph RL, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled study of once daily venlafaxine extended release of outpatients with GAD [Abstract]. American Psychiatric Association.

1998: 241. Abstract NR643.

36.

Almeida JC, Grimsley EW. Coma from the health food store: interaction between kava and alprazolam

[Letter]. Ann Intern Med 1996;125:940-1.

37.

Schelosky L, Raffauf C, Jendroska K, Poewe W. Kava and dopamine antagonism [Letter]. J Neurol

Neurosurg Psychiatry 1995;58:639-40.

38.

Norton SA, Ruze P. Kava dermopathy. J Am Acad Dermatol 1994;31:89-97.

39.

Garges HP, Varia I, Doraiswamy PM. Cardiac complications and delirium associated with valerian root withdrawal [Letter]. JAMA 1998;280:1566-7.

Copyright © 2000 by the American Academy of Family Physicians.

This content is owned by the AAFP. A person viewing it online may make one printout of the material and may use that printout only for his or her personal, non-commercial reference. This material may not otherwise be downloaded, copied, printed, stored, transmitted or reproduced in any medium, whether now known or later invented, except as authorized in writing by the AAFP. Contact afpserv@aafp.org

for copyright questions and/or permission requests.

CLINICAL EVIDENCE:

A PUBLICATION OF BMJ PUBLISHING GROUP

Generalized Anxiety Disorder

CHRISTOPHER K. GALE, Consultant Psychiatrist, University of Auckland, Auckland, New

Zealand

MARK OAKLEY-BROWNE, Professor, University of Monash, Victoria, Australia

Questions Addressed

What are the effects of treatments?

Summary of Interventions

Beneficial

Cognitive therapy

Likely to be beneficial

Buspirone

Certain antidepressants (paroxetine, imipramine, trazodone, opipramol, venlafaxine)

Trade off Unknown

Benzodiazepines effectiveness

Kava Applied relaxation

Hydroxyzine

Abecarnil

Antipsychotic drugs

Beta blockers

Definition Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) is defined as excessive worry and tension about everyday events and problems, on most days, for at least six months to the point where the person experiences distress or has marked difficulty in performing day-to-day tasks.

1 It may be characterized by the following symptoms and signs: increased motor tension

(fatigability, trembling, restlessness, and muscle tension); autonomic hyperactivity (shortness of breath, rapid heart rate, dry mouth, cold hands, and dizziness); and increased vigilance and scanning (feeling keyed up, increased startling, and impaired concentration), but not panic attacks.

1 One nonsystematic review of epidemiologic and clinical studies found marked reduction of quality of life and psychosocial functioning in people with anxiety disorders

(including GAD).

2 It also found that (using the Composite Diagnostic International

Instrument) people with GAD have low overall life satisfaction and some impairment in ability to fulfill roles, social tasks, or both.

2

Incidence/Prevalence Assessment of the incidence and prevalence of GAD is difficult, because a large proportion of people with GAD have a comorbid diagnosis. One nonsystematic review identified the U.S. National Comorbidity Survey, which found that more than 90 percent of people diagnosed with GAD had a comorbid diagnosis, including dysthymia (22 percent), depression (39 to 69 percent), somatization, other anxiety disorders, bipolar disorder, or substance abuse.

3 The reliability of the measures used to diagnose GAD in epidemiologic studies is unsatisfactory.

4,5 One U.S. study, with explicit diagnostic criteria

(DSM-III-R), estimated that 5 percent of people will develop GAD at some time during their lives.

5 A recent cohort study of people with depressive and anxiety disorders found that 49 percent of people initially diagnosed with GAD retained this diagnosis after two years.

6 One nonsystematic review found that the incidence of GAD in men is only one half the incidence in women.

7 One nonsystematic review of seven epidemiologic studies found reduced prevalence of anxiety disorders in older people.

8 Another nonsystematic review of 20 observational studies in younger and older adults suggested that the autonomic arousal to stressful tasks is decreased in older people, and that older people become accustomed to stressful tasks more quickly than younger people.

9

Etiology/Risk Factors One community study and a clinical study have found that GAD is associated with an increase in the number of minor stressors, independent of demographic factors, 10 but this finding was common in people with other diagnoses in the clinical population.

6 One nonsystematic review (five case control studies) of psychologic sequelae to civilian trauma found that rates of GAD reported in four of the five studies were increased significantly compared with a control population (rate ratio: 3.3; 95 percent confidence interval [CI]: 2.0 to 5.5).

11 One systematic review of cross-sectional studies found that bullying (or peer victimization) was associated with a significant increase in the incidence of

GAD (effect size: 0.21).

12 One systematic review (search date not stated) of the genetic epidemiology of anxiety disorders (including GAD) identified two family studies and three twin studies.

13 The family studies (45 index cases; 225 first-degree relatives) found a significant association between GAD in the index cases and in their first-degree relatives

(odds ratio [OR]: 6.1; 95 percent CI: 2.5 to 14.9). The twin studies (13,305 people) estimated that 31.6 percent (95 percent CI: 24 to 39 percent) of the variance to liability to GAD was explained by genetic factors.

13

Prognosis GAD often begins before or during young adulthood and can be a lifelong problem.

14 Spontaneous remission is rare.

Clinical Aims To reduce anxiety; to minimize disruption of day-to-day functioning; and to improve quality of life, with minimum adverse effects.

Clinical Outcomes Severity of symptoms and effects on quality of life, as measured by symptom scores: usually the Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAM-A), State-Trait Anxiety

Inventory, or Clinical Global Impression Symptom Scores. Where numbers needed to treat are given, these represent the number of people requiring treatment within a given time period

(usually six to 12 weeks) for one additional person to achieve a certain improvement in symptom score. The method for obtaining numbers needed to treat was not standardized across studies. Some used a reduction by, for example, 20 points in the HAM-A as a response, others defined a response as a reduction, for example, by 50 percent of the premorbid score. We have not attempted to standardize methods, but instead have used the response rates reported in each study to calculate numbers needed to treat. Similarly, we have calculated numbers needed to harm from original trial data.

Evidence-Based Medicine Findings

SEARCH DATE: CLINICAL EVIDENCE UPDATE SEARCH AND APPRAISAL

FEBRUARY 2002

Cognitive Therapy

Two systematic reviews and one nonsystematic review have found that cognitive behavior therapy, using a combination of interventions such as exposure, relaxation, and cognitive

restructuring, improves anxiety and depression over four to 12 weeks more than remaining on a waiting list (no treatment), anxiety management training alone, relaxation training alone, or nondirective psychotherapy. One systematic review found limited evidence (by making indirect comparisons of treatments across different randomized controlled trials [RCTs]) that more people given individual cognitive therapy maintained recovery after six months than those given nondirective treatment, group cognitive therapy, group behavior therapy, individual behavior therapy, or analytic psychotherapy, but that fewer people maintained recovery after six months with cognitive therapy versus applied relaxation. One subsequent

RCT found no significant difference in symptoms at 13 weeks with cognitive therapy versus applied relaxation. Another subsequent RCT in people older than 55 years with a variety of anxiety disorders found that cognitive behavior therapy versus supportive counseling significantly improved symptoms of anxiety over 12 months, but found no significant difference in symptoms of depression.

Applied Relaxation

We found no RCTs of applied relaxation versus placebo or no treatment. One systematic review found limited evidence, by making indirect comparisons of treatments across different

RCTs, that more people given applied relaxation maintained recovery after six months than those given individual cognitive therapy, nondirective treatment, group cognitive therapy, group behavior therapy, individual behavior therapy, or analytic psychotherapy. One subsequent RCT found no significant difference in symptoms at 13 weeks with applied relaxation versus cognitive behavior therapy.

Benzodiazepines

One systematic review and one subsequent RCT found limited evidence that benzodiazepines versus placebo reduced symptoms over two to nine weeks. However, RCTs and observational studies found that benzodiazepines increased the risk of dependence, sedation, industrial accidents, and road traffic accidents. One nonsystematic review found that, if used in late pregnancy or while breast feeding, benzodiazepines may cause adverse effects in neonates.

Limited evidence from RCTs found no significant difference in symptoms over six to eight weeks with benzodiazepines versus buspirone, abecarnil, or antidepressants. One systematic review of poor quality RCTs found insufficient evidence about the effects of long-term treatment with benzodiazepines.

Buspirone

RCTs have found that buspirone versus placebo significantly improves symptoms over four to nine weeks. Limited evidence from RCTs found no significant difference in symptoms over six to eight weeks with buspirone versus antidepressants or hydroxyzine.

Hydroxyzine

One RCT identified by a nonsystematic review found that hydroxyzine versus placebo significantly improved symptoms of anxiety after four weeks. Another RCT identified by the review found no significant difference in the proportion of people with improved symptoms of anxiety at 35 days with hydroxyzine versus placebo or buspirone.

Abecarnil

One RCT found no significant difference in symptoms at six weeks with abecarnil versus placebo or versus diazepam. One smaller RCT found limited evidence that low-dose abecarnil versus placebo significantly improved symptoms.

Antidepressants

RCTs have found that imipramine, opipramol, paroxetine, trazodone, or venlafaxine versus placebo significantly improved symptoms over four to eight weeks, and that they are not significantly different from each other. RCTs and observational studies have found that antidepressants are associated with sedation, dizziness, nausea, falls, and sexual dysfunction.

Limited evidence from RCTs found no significant difference in symptoms over eight weeks with antidepressants versus benzodiazepines or buspirone. We found no systematic review or

RCTs assessing sedating tricyclic antidepressants in people with GAD.

Antipsychotic Drugs

One RCT found that trifluoperazine versus placebo significantly reduced anxiety after four weeks, but caused more drowsiness, extrapyramidal reactions, and other movement disorders.

Beta Blockers

We found no RCTs assessing use of beta blockers in people with GAD.

Kava

One systematic review in people with anxiety disorders, including GAD, found that kava versus placebo significantly reduced symptoms of anxiety over four weeks. Observational evidence suggests that kava may be associated with hepatotoxicity.

Adapted with permission from Gale CK, Oakley-Browne M. Generalised anxiety disorder. Clin

Evid 2002;8:974-90.

EDITOR'S NOTE: Abecarnil and opipramol are not available in the United States.

Both authors have received funding from Eli Lilly.

REFERENCES

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed.

Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1994.

2. Mendlowicz MV, Stein MB. Quality of life in individuals with anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry

2000;157:669-82.

3. Stein D. Comorbidity in generalised anxiety disorder: impact and implications. J Clin Psychiatry

2001;62(suppl 11):29-34. (review).

4. Judd LL, Kessler RC, Paulus MP, et al. Comorbidity as a fundamental feature of generalised anxiety disorders: results from the national comorbidity study (NCS). Acta Psychiatry Scand

1998;98(suppl 393):6-11.

5. Andrews G, Peters L, Guzman AM, et al. A comparison of two structured diagnostic interviews:

CIDI and SCAN. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 1995;29:124-32.

6. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the national comorbidity survey. Arch Gen

Psychiatry 1994;51:8-19.

7. Seivewright N, Tyrer P, Ferguson B, et al. Longitudinal study of the influence of life events and personality status on diagnostic change in three neurotic disorders. Depression Anx

2000;11:105-13.

8. Pigott T. Gender differences in the epidemiology and treatment of anxiety disorders. J Clin

Psychiatry 1999;60(suppl 18):15-8.

9. Jorm AF. Does old age reduce the risk of anxiety and depression? A review of epidemiological studies across the adult life span. Psychol Med 2000;30:11-22.

10. Lau AW, Edelstein BA, Larkin KT. Psychophysiological arousal in older adults: a critical review.

Clin Psychol Rev 2001;21:609-30. (review).

11. Brantley PJ, Mehan DJ Jr, Ames SC, et al. Minor stressors and generalised anxiety disorders among low income patients attending primary care clinics. J Nerv Ment Dis 1999;187:435-40.

12. Brown ES, Fulton MK, Wilkeson A, Petty F. The psychiatric sequelae of civilian trauma. Comp

Psychiatry 2000;41:19-23.

13. Hawker DS, Boulton MJ. Twenty years' research on peer victimisation and psychosocial maladjustment: a meta-analytic review of cross-sectional studies. J Child Psychol Psychiatr

2000;41:441-5.

14. Hettema JM, Neale MC, Kendler KS. A review and meta-analysis of the genetic epidemiology of anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:1568-78. Search date not stated; primary source

Medline.

This is one in a series of chapters excerpted from Clinical Evidence , published by the BMJ

Publishing Group, Tavistock Square, London, United Kingdom. Clinical Evidence is published in print twice a year and is updated monthly online. Each topic is revised every eight months, and users should view the most up-to-date version at www.clinicalevidence.com

. This series is part of the AFP 's CME. See "Clinical Quiz" on page 29 .