Resources - League of Women Voters

advertisement

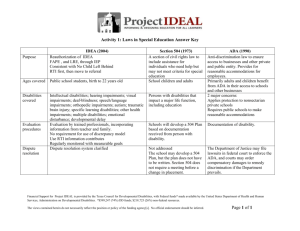

THE ROLE OF THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT IN PUBLIC EDUCATION: LEGISLATION AND FUNDING FOR THE EDUCATION OF CHILDREN WITH SPECIAL NEEDS In 1965, the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) was passed by Congress. ESEA was the center of President Johnson’s War on Poverty and was influenced by the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The children who were covered by ESEA in 1965 included those who were disabled and covered by an amendment to the original ESEA (Title IV – Aid to handicapped children). Within the next decade, the education of disabled children was funded by a separate law: the Education for All Handicapped Children Act of 1975 (EAHCA). Over a 35year span, the law was reauthorized and became the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), the latest of which was reauthorized in 2004 and called the Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act (IDEIA). The upcoming reauthorization of ESEA will also influence how IDEIA is administered and practiced. IDEIA has four sections that cover the Free and Appropriate Education (FAPE) of 6.6 million disabled children who are age 0-21. Part A (General Provisions) Part B (Assistance for Education of All Children with Disabilities) Part C (Infants and Toddlers with Disabilities) Part D (National Activities to Improve Education of Children with Disabilities) Mandates in Special Education Funding Funding requires adherence to the federal mandates. The most important mandate is the zero-reject policy, under which no child is turned away from educational services. To qualify for special education service, a student must be classified with one (or more) of 13 disabilities now covered by IDEIA. The definition of “a child with a disability” is found in the United States Code, Title 29 1401(3) (A): 3) The term ‘child with a disability’ means a child— (i) with mental retardation, hearing impairments (including deafness), speech or language impairments, visual impairments (including blindness), serious emotional disturbance (referred to in this chapter as “emotional disturbance”), orthopedic impairments, autism, traumatic brain injury, other health impairments, or specific learning disabilities; and (ii) Who, by reason thereof, needs special education and related services. The federal government demands that states submit plans for the distribution of monies to local agencies for direct instructional programming that adhere to federal mandates. Under each state’s laws, an Individualized Educational Program (IEP) is constructed for each child receiving services. The purpose of an IEP is to assure the student of a FAPE, as ensured by law. The child is to be placed in the Least Restrictive Environment (LRE) for education. In order to qualify for federal funds, state and local agencies are bound to federal guidelines to specify identification procedures and the placement of disabled children. State grant applications for federal funds must include a plan for distribution of the funds to local education agencies (LEAs), as well as sufficient time for the general public to review and comment on the state plan. LEAs receive allotments from the state for their district special education needs. The shortfall in funding then needs to be addressed by the local education agencies. CURRENT FUNDING CHALLENGES Federal Underfunding: The Education for All Handicapped Children Act (1975) included legislation for funding local programs through state distribution of 40 percent of the cost. “Full funding” (40 percent) has never happened; the actual amount has varied. There were federal funds covering from 8 to 10 percent of the cost to states ten years ago, according to Katsiyannis, et al. (2001). The FY 2012 U.S. Department of Education Budget lists 17 percent as the current figure, with an estimated $1,765 cost per pupil. The allotment has increased 1.7 percent in the FY 2012. Increasing enrollment: Special education enrollment has grown, from 3.8 million in 1973 to 6.6 million in 2011. Federal special education support increases for FY 2012 are held at 1.7 percent over FY 2011. Maintenance of effort: Because of severe financial straits, more states are applying for waivers to the spending requirement by the federal government for special education funding. The waiver, called a Maintenance of Effort (MOE) has not been easily obtained and involves holding a spending pattern based on the previous year. Waivers were given to Iowa, West Virginia, and Kansas last year; waivers are pending for New Jersey, South Carolina and Alabama (Shah, 2011). Inclusion and training: Currently, ninetyfive percent of disabled children are educated in inclusive classrooms, the rest being educated in separate classes, institutions or at home. An increase in inclusion practices is a strong possibility for fund-strapped districts (Shah, 2011). The balancing act – attention to finances, while providing for children’s needs – continues to be precarious, and it is also critical to provide teachers with quality in-service training. References Katsiyannis, A., Yell, M. & Bradley, R. (2001). Reflections on the 25th anniversary of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. Remedial and Special Education, Vol.22, (6), 324-34. Shah, N. (2011, February 14). States expected to seek special education funding waivers. Education Week. Retrieved from http://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/ 2011/02/09/20speced.h30.html U.S. Department of Education. Fiscal Year 2012 Budget Overview. Supporting Individuals with Disabilities. Retrieved from http://www2.ed.gov/ about/overview/budget/budget12/summary/edlitesection2b.html U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. Digest of Education Statistics. Chapter 2, Table 45. Children 3 to 21 years served under Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, Part B, by type of disability: Selected years, 1976 through 2008-09. Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/ programs/digest/d10/tables/dt10_045.asp?referrer=lis t U.S. Department of Education (2004). Retrieved from http://www.ed.gov/policy/speced/guid/idea/ idea2004.html. Special Education Legislation Milestones DECADE 1950 CASE/LEGISLATION 1954: Brown v. Board of Education 1960 Bureau of Handicapped Created. 1970 Education 1965: Elementary and Secondary Amendment to original ESEA Title IV – Aid to Education Act became law. handicapped children. 1972: PARC v Ruled: Disabled have equal rights. Pennsylvania and Mills v. Board of Education 1973: Section 504 of Rehabilitation Act became law. 1980 1990 2000 RESULT Paved the way for special needs children to receive better education, but at this time children were still denied an education based on their disability. for No funding for handicapped under federal or state law. the Protected disabled individuals discrimination due to disability. from 1974: Family Educational Rights and Parents gained access to all information Privacy Act (FERPA) became law. maintained by a school district on their students. 1975: Education for All Handicapped Children Act (EAHCA) became law, Free appropriate public education for all handicapped students. 1986: Addition of Handicapped Mandated that all school students and parents Children’s Protection Act to have rights under both Section 504 and EAHCA. EAHCA. 1990: EAHCA amended and called IDEA reauthorized. Additions include students Individuals with Education to be included in state and national Disabilities Act (IDEA). assessments, inclusion (Least Restrictive Environment, LRE). Regular classroom 1996: I DEA reauthorized. teachers now required to take part in an Individual Education Plan (IEP) team. 2001: No Child Left Behind became Accountability at state and local levels the title of the Elementary and required. School districts are required to Secondary Education Act. provide more instruction and interventions to help prevent enrollment in special education. 2004: Reauthorization of IDEA (P.L. Response to Intervention (RTI) gains 101-476) now called IDEIA. momentum as a screening tool. Students are expected to take responsibility for their behavior and are subject to the same rules as the rest of the students. Produced by the LWVUS The Education Study: The Role of the Federal Government in Public Education © 2011 by the League of Women Voters of the United States