Lecture Transcript #5

advertisement

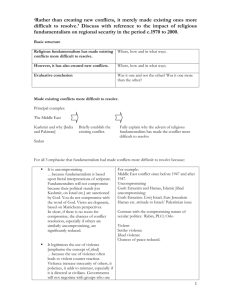

Mini-Lecture © Robert J. Brym (2004) #5 Fundamentalism and Extremist Politics in the Arab World In 1972 I was doing my BA at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. One morning at the end of May, I switched on the radio to discover that a massacre had taken place at Lod (now Ben Gurion) International Airport outside Tel Aviv, just 26 miles from my apartment. Three Japanese men dressed in business suits had arrived on Air France flight 132 from Paris. They were members of the Japanese Red Army, a small, shadowy terrorist group with links to the General Command of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine. Both groups wanted to help wrest Israel from Jewish rule. After they picked up their bags, the three men pulled out automatic rifles and started firing indiscriminately. Before pausing to slip fresh clips into their rifles, they lobbed hand grenades into the crowd at the ticket counters. One man ran onto the tarmac, shot some disembarking passengers, and then blew himself up. This was the first suicide attack in Middle East history. Security guards shot a second terrorist and arrested the third, Kozo Okamoto. When the firing stopped, 26 people lay dead. Half were non-Jews. In addition to the two terrorists, eleven Catholics were murdered. They were Puerto Rican tourists who had just arrived on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. Both the Japanese Red Army and the General Command of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine were strictly non-religious organizations. Their members were atheists who quoted Marx and Lenin, not Jesus or Muhammad. Yet something unexpected happened to Kozo Okamoto, the sole surviving terrorist of the Lod massacre. Israel sentenced him to life in prison but freed him in 1985 in a prisoner exchange with Palestinian forces. Okamoto wound up living in Lebanon's Bekaa Valley, the main base of the Iranian-backed Hizbollah fundamentalist terrorist organization. At some point in the late 1980s or early 1990s, he was swept up in the Middle East's Islamic revival. Okamoto the militant atheist converted to Islamic fundamentalism. Kozo Okamoto's life tells us something important and not at all obvious about religious fundamentalism and politics in the Middle East and elsewhere. Okamoto was involved in extremist politics first and became a religious fundamentalist later. Religious fundamentalism became a useful way for him to articulate and implement his political views. This is quite typical. Religious fundamentalism often provides a convenient vehicle for framing political extremism, enhancing its appeal, legitimizing it, and providing a foundation for the solidarity of political groups. Many people fail to see the political underpinnings of religious fundamentalism. They regard religious fundamentalism as an independent variable and extremist politics as a dependent variable. In this view, some people happen to become religious fanatics and then their fanaticism commands them to go out and kill their opponents. For example, here is what President George W. Bush said when he addressed Congress on September 20, 2001, just nine days after al Qaeda's attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. Al Qaeda's goal, said President Bush, is "imposing its radical beliefs on people everywhere. The terrorists practice a fringe form of Islamic extremism…. The terrorists' directive commands them to kill Christians and Jews, to kill all Americans, and make no distinction among military and civilians, including women and children." Islamic extremism somehow appears, and the murdering inevitably follows. What President Bush ignored are the political sources of this fringe form of Islamic extremism. Al Qaeda is strongly antagonistic to American foreign policy in the Middle East. It despises U.S. support for repressive and non-democratic Arab governments like that of Kuwait and Saudi Arabia, which fail to distribute the benefits of oil wealth to the impoverished Arab masses. It is also virulently opposed to the American position on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, which it regards as too pro-Israeli and insufficiently supportive of Palestinian interests (to put it mildly). These political complaints are the breeding ground of support for al Qaeda in the Arab world. This is evident from recent public opinion polls, which show that Arabs in the Middle East hold largely favorable attitudes toward American culture, democracy, and the American people, but extremely negative attitudes toward precisely those elements of American Middle East policy that al Qaeda opposes. Al Qaeda and other terrorist organizations in the Middle East gain in strength to the degree that these political issues are not addressed in a meaningful way. As Zbigniew Brzezinski, national security advisor to President Jimmy Carter, recently wrote in the New York Times: "To win the war on terrorism, one must…set two goals: first, to destroy the terrorists and, second, to begin a political effort that focuses on the conditions that brought about their emergence." These are wise words. They are based on the sociological understanding that fundamentalism, like other forms of religion, is powerfully influenced by the social context in which it emerges.