Chapter 11 Depreciation

advertisement

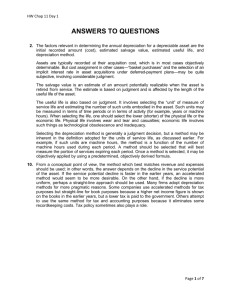

Chapter 11 DEPRECIATION Depreciation is a systematic and rational way to allocate the cost of long-lived tangible assets over their useful lives. This satisfies the goal of matching costs and revenues. Done because fair values change and are difficult to measure. Depreciation—long-lived tangible assets. Depletion—natural resources. Amortization—intangible assets. Accounting 302 L.DuCharme Chapter 11 -1- Information needed in order to calculate depreciation: (1) depreciable base = original cost – salvage value. (2) estimated service (useful) life versus physical life. (3) depreciation method:** Activity based—units of use or production. Straight-line—based on calendar time. Accelerated—SoYD or declining-balance. Special—group & composite, retirement & replacement, hybrid, combination, other. ** All take the same total depreciation over an asset’s useful life. Accounting 302 L.DuCharme Chapter 11 -2- Activity-based methods Big Steel uses an activity-based depreciation method. They have equipment with a cost of $250,000, salvage value of $10,000 and estimated useful life of 20,000 hours. In 2003, Big Steel used the equipment 3,000 hours. How much depreciation on this equipment should they recognize for 2003? $240,000 * 3,000 hrs. = $36,000 20,000 hrs. Why would some companies want to use this approach? Accounting 302 L.DuCharme Chapter 11 -3- Straight-line method Simple & widely used. Depreciation is function of time only. Big Steel uses straight-line depreciation. They have equipment with a cost of $250,000, salvage value of $10,000 and estimated useful life of 10 years. Equipment was purchased 1/1/2002. In 2003, Big Steel used the equipment 3,000 hours. How much depreciation on this equipment should they recognize for 2003? $240,000 / 10 = $24,000 (each year for 10 years) Accounting 302 L.DuCharme Chapter 11 -4- Accelerated Depreciation Methods (aka Decreasing-Charge methods) These methods take more depreciation in the early years of an asset’s life. Two most used are: (1) Sum-of-years’-digits and (2) declining-balance [200% or 150%]. SoYD = n(n+1) / 2 Where n = useful life in years. SoYD = 10(11) / 2 = 55 for a 10-year asset or (10 + 9 + 8……+ 2 + 1) Big Steel uses Sum-of-years’-digits depreciation method. They have equipment with a cost of $250,000, salvage value of $10,000 and estimated useful life of 10 years. Equipment was purchased on 1/1/2002. How much depreciation on this equipment should they recognize for 2003? Year 2002 2003 2004 2005 ….. ….. 2011 Accounting 302 Deprec. base $240,000 “ “ “ “ “ “ L.DuCharme Remain life 10 9 8 7 . . 1 Chapter 11 Depre. fraction 10/55 9/55 8/55 7/55 . . 1/55 Depreciation $43,636.34 39,272.12 34,904.08 4,363.63 -5- Declining-Balance Method Apply some constant rate to the beginning of period book-value of the asset. Rate is defined usually as 1.5 or 2 times the straight-line rate (e.g., 20% is twice the straight-line rate for a 10-year asset). Remember to not depreciate the asset to below its salvage value—therefore might have to take less than calculated depreciation in years close to end of life (maybe 0). If low SV, might have to take more depreciation in last year or switch to SL when greater depreciation. Big Steel uses double-declining-balance depreciation method. They have equipment with a cost of $250,000, salvage value of $10,000 and estimated useful life of 10 years. Equipment was purchased on 1/1/2002. How much depreciation on this equipment should they recognize for 2003? * switch to straight-line Year BV begin of period 2002 $250,000 2003 $200,000 2004 $160,000 2005 $128,000 2006 $102,400 2007 $81,920 2008 $65,536 2009 $51,652 2010 $37,768 2011 $23,884 Accounting 302 L.DuCharme Rate 20% 20% 20% 20% 20% 20% .25* .25 .25 .25 Depreciation Expense $50,000 $40,000 $32,000 $25,600 $20,480 $16,384 $13,884 $13,884 $13,884 $13,884 Chapter 11 A/D balance (EOP) $50,000 $90,000 $122,000 $147,600 $168,080 $184,464 $198,348 $212,232 $226,116 $240,000 BV EOP $200,000 $160,000 $128,000 $102,400 $81,920 $65,536 $51,652 $37,768 $23,884 $10,000 -6- Clarification on the “switch to straight-line” when using declining-balance method for depreciation: Companies do like the “distortion” in the later years when declining methods take little or no depreciation (high salvage value) or a large amount in the last year (low salvage value)—so they switch to straight-line when straight-line depreciation would be higher. To test if the straight-line amount would be more, you divide the remaining amount to be depreciated (balance – salvage value) by the number of remaining years. To avoid a test every year, they might have a policy to switch at the midpoint of the asset’s useful life. For GAAP, companies do not have to switch if they do not want to. For tax, the switch is required and already in the tax tables for all to use. So, the government allows you to pay less tax for year of switch! Accounting 302 L.DuCharme Chapter 11 -7- Other Depreciation Methods GAAP allows companies to develop their own custom methods. Only requirement is that the asset’s cost be allocated in a systematic and rational manner over its useful life. Group & Composite Methods: Group—similar assets Composite—dissimilar assets Both use average depreciation and this simplifies bookkeeping costs. Hybrid/combination Methods: use more than one method. E.g., depreciate part of cost using straightline and the remainder with activity. Accounting 302 L.DuCharme Chapter 11 -8- Partial Period Depreciation Firms seldom purchase depreciable assets on the first day of the period. There are several ways to handle the depreciation for the first and last period in this situation. Prorate using nearest full month or fraction of year. Half year in year of purchase, and half year in year of disposal (called “half-year” convention, used for tax purposes). Full years’ depreciation in year of purchase, none in year of disposal. No depreciation in year of purchase, full year’s in year of disposal. Accounting 302 L.DuCharme Chapter 11 -9- Revisions (changes) in depreciation estimates. Salvage value and/or useful life estimates can change anytime. This is not handled as an error. Change will be made in the current and future periods. Simply calculate a new rate based on the remaining life and total depreciable amount remaining after the change. For straight-line: New rate = remaining amount to be depreciated remaining useful life Accounting 302 L.DuCharme Chapter 11 - 10 - Impairments—SFAS # 144 Conservatism—PPE that is held for use is never written up, but will be written down in the case of an impairment. Events lead to possibility of an impairment. Recoverability test: If the sum of future net undiscounted cash flows is less than the carrying amount of the asset, than an impairment has occurred. If an impairment, how much? Impairment loss = CV – FairV of asset If no FairV, then use discounted future cash flows. Use the risk-free rate of interest as the discount rate. Loss on impairment A/D xxx xxx Other gains and losses section of IS. Assets held for disposal: valued at the lower of cost or net realizable value. Written up or down each period, but has to be no more than the CV prior to impairment. Accounting 302 L.DuCharme Chapter 11 - 11 - Depletion of natural resources (wasting assets) Oil & gas, minerals, timber, coal….. Accounting is similar to PPE. Depletion base: includes acquisition cost of resource (not land) + exploration cost + intangible development cost + restoration cost. If exploration efforts are successful then capitalize, otherwise expense. Depletion expense is calculated similar to how depreciation based on units-of-production is done. Entry to record the depletion for the period is Inventory XXX Accum. Depletion XXX Depletion expense is included in CoGS for the period. Accounting 302 L.DuCharme Chapter 11 - 12 - It is often very difficult to estimate the amount of recoverable resources and changes in estimates are common (handled exactly like change in useful life for depreciation). Interesting tax law issues with oil & gas and most minerals (including gravel). Tax law allows for deduction of cost or percentage-depletion based on gross revenue, whichever is greater! % varies from 5-22%. This means that depletion can exceed the cost of some natural resources! Accounting 302 L.DuCharme Chapter 11 - 13 - Very interesting history of an accounting controversy on pages 539-541 of the text, re: successful-efforts versus full-cost for the oil and gas industry. The story underscores the political nature of accounting rules. 1977—SFAS #19, must use successful efforts. 1978—outrage by small O&G companies, SEC wants Reserve Recognition Accounting which is a current value vs. cost approach. 1979—FASB issues #25—suspends #19. 1981—SEC drops RRA, FASB issues #69 (requires current value disclosure). Currently, back to pre-1977 GAAP, either full or successful-efforts is allowed. Full cost has a ceiling (PV of company reserves). Accounting 302 L.DuCharme Chapter 11 - 14 - Income Tax Depreciation 1981—ACRS, assets placed in service 1981-1986 1986—MACRS, for assets placed in service 1987 and later. (1) all depreciable assets are placed into property classes. This determines the tax life, which is generally shorter than the useful life. (2) depreciation rate depends on class, most are declining-balance. (3) salvage value = 0. Depreciate for tax to zero value. (4) half-year convention. (5) switch to SL when it gives more depreciation. Optional approach is allowed for tax—Straight-line. Only point (2) above would change. Because companies use a different method for financial reporting and tax, a difference exists in tax expense and tax payable. This will be dealt with in Acctg. 303. Accounting 302 L.DuCharme Chapter 11 - 15 - Analysis of PPE and Natural Resources RATE OF RETURN ON TOTAL ASSETS (ROA) Rate of Return on Total Assets = Profit Margin on sales x Asset turnover = Net Income Net Sales = x Net Sales Average Total Assets Net Income Average Total Assets Example (in million of $): Net sales Total Assets (1/1) Total Assets (12/31) Net Income $1,500 1,200 1,400 150 ROA = $150 x $1,500 $1,500 (1,200 + 1,400) / 2 = 0.10 x 1.15 = 11.5% Accounting 302 L.DuCharme Chapter 11 - 16 - OIL AND GAS ACCOUNTING ► Two generally accepted methods to account for oil and gas exploration costs are: * The successful efforts method requires that exploration costs that are known not to have resulted in the discovery of oil or gas (sometimes referred to as dry holes) be included as expenses in the period the expenditures are made. * The full-cost method allows costs incurred in searching for oil and gas within a large geographical area to be capitalized as assets and expensed in the future as oil and gas from the successful wells are removed from that area. The Shannon Oil Company incurred $2,000,000 in exploration costs for each of 10 oil wells drilled in 2000 in West Texas. Eight of the 10 wells were dry holes. The accounting treatment of the $20 million in total exploration costs will vary significantly depending on the accounting method used. The summary journal entries using each of the alternative methods are as follows: Successful Efforts Full Cost Oil deposit 4,000,000 Oil deposit 20,000,000 Exploration expense 16,000,000 Cash 20,000,000 Cash 20,000,000 Accounting 302 L.DuCharme Chapter 11 - 17 -

![Quiz chpt 10 11 Fall 2009[1]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/005849483_1-1498b7684848d5ceeaf2be2a433c27bf-300x300.png)