Turning Ireland English

advertisement

Turning Ireland English

By Professor Steven Ellis

The question of how to govern Ireland was one of the most difficult and sensitive issues of

Elizabeth's reign. By the time of her death, the country had forged a new and distinct identity of its

own. But what kind of policies did her government pursue and how did the people of Ireland

react?

A land of contrasts

For Elizabeth, Ireland was very much 'an unwelcome inheritance'. The island witnessed the last

private battle between Tudor magnates (the earls of Desmond and Ormond at Affane, Co.

Waterford, 1565), and was also the destination of the largest army to leave England during the

reign (17,300 men, 1599). Yet the conquest of Gaelic Ireland was long unintended, even though it

constituted the Tudor regime's most ambitious undertaking (entailing the thorough Anglicisation

of government and society) and the only significant addition to Tudor territory.

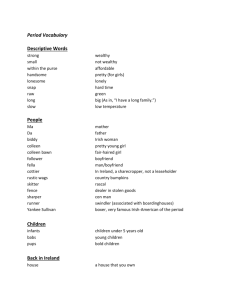

Ireland in 1558 was divided politically and culturally into English and Gaelic parts. The

predominantly Gaelic west and north had a scanty, shifting population, with scattered, largely

impermanent settlements, and a predominantly pastoral economy. A common legal system, social

and cultural institutions also stretched across the North Channel into the Scottish highlands and

islands, imparting some measure of unity. Yet Gaelic politics were intensely local, with the

numerous rival clans and chieftaincies. This was, according to English officials, 'a land of war',

inhabited by a rude and savage people ('the wild Irish') living in bogs and mountains.

'...the conquest of Gaelic Ireland was long unintended, even though it constituted the Tudor

regime's most ambitious undertaking...'

The smaller, more 'civil', 'Englishry' (the English Pale around Dublin and the south) contained

numerous English-style towns and villages and prided itself on its Englishness and loyalty. Yet

Gaelic practices and speech were spreading among those of English descent (the future Old

English) and the costs of defending the queen's subjects there had lately escalated alarmingly. The

troops were paid in 'harp groats' (heavily debased English-style coins, distinguishable by harps on

the reverse), but administrative costs still exceeded income by £25,000 - 10 per cent of

Elizabeth's total revenues. Reflecting the militarisation of society, moreover, English landowners

still lived in defended towerhouses (outside the towns and the inner Pale), their tenants (and many

Gaelic clansmen) in wattle and daub cabins.

Options for reform

Elizabeth's first governor, the earl of Sussex, remarked candidly that he had often wished Ireland

'to be sunk in the sea'. Withdrawal was unthinkable, however, both for reasons of prestige, and

because of the danger that France, or later Spain, might establish control. Nor was there any glory

or profit in conquering a wilderness: conquest, while feasible, would require a substantial army to

drive the Irish out of their homes in woods and bogs, and an enormous effort subsequently to hold

the country with garrisons and colonies.

'...conquest, while feasible, would require a substantial army to drive the Irish out of their homes

in woods and bogs...'

Faced with these unacceptable alternatives, Elizabeth's father, King Henry VIII, had sought an

economical middle way to bring the island under English rule. Declaring himself king of Ireland

(1541), Henry had tried to cajole the Gaelic chiefs 'by sober ways, politic drifts and amiable

persuasions' to accept English rule, offering them secure titles to their land and a role in

government in return for their abandonment of Gaelic law,language and customs in favour of

English ways. This strategy for transforming Gaelic warlords into English landlords ('surrender

and regrant') remained a central plank of Tudor reform throughout Elizabeth's reign. Yet progress

was slow, despite initial optimism when O'Brien and O'Neill had visited court to receive their new

titles as earls of Thomond and Tyrone (1542-3).

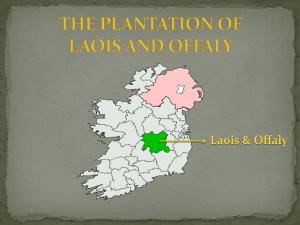

Under Edward VI and Mary, English financial and military subventions were stepped up in a bid

to force the pace, but increased coercion proved counterproductive, and the growing levels of

violence alienated the local Englishry. In particular, an experiment with limited colonisation in

Leix-Offaly proved disastrously expensive, requiring large garrisons to repel the expropriated

O'Mores and O'Connors after the shiring of their lordships as Queen's and King's Counties (1557).

Elizabeth's policy

Elizabeth's basic instinct - particularly following peace and the withdrawal of French troops from

Scotland (1559-60) - was to delay, so saving expenses. Only in the face of a grave emergency - a

major rebellion or, later, the growing threat of Spanish intervention - would she authorise vigorous

measures to protect English interests. Such a policy (if it can be so described) pleased no-one.

The border chieftaincies remained restive, fearing expropriation by English captains intruded to

control them; New English officials and captains sought to establish themselves as landed gentry

and grew frustrated at Elizabeth's mild dealings with the Irishry; Old English landowners were

alienated by the burden of maintaining an enlarged English army and the abrasive conduct of army

captains; and the queen's ministers in England were perplexed both at the costs of governing a

remote borderland and at the ineffectiveness in Ireland of traditional Tudor methods of

consolidating crown control over outlying parts. Since the 1530s, Wales and the English north had

been reformed by extending the reach of English law and local government (abolishing feudal

franchises and reducing 'overmighty subjects') so as to promote 'good rule' and 'English civility'.

Yet in Ireland the military frontier frustrated similar attempts to enlarge the English Pale.

'...political considerations generally took priority over religious conformity...'

The Reformation crisis also fuelled the government's fears about rebellion in Ireland. All three

borderlands were 'backward in religion', but the queen feared that a crackdown on Catholic dissent

as urged by her bishops and ministers might unite religious and political dissidents, driving

Catholic loyalists into the arms of Gaelic rebels like Shane O'Neill (1559-67) who was intriguing

with Scotland and France. Elizabeth personally expressed a desire to learn Gaelic, and demanded a

Gaelic translation of the New Testament from her bishops - in line with the Protestant insistence

on the use of the vernacular in church services - but others feared that Gaelic services would

undermine the government's programme to make Ireland English. Thus, political considerations

generally took priority over religious conformity: Gaelic translations of the Bible and Book of

Common Prayer only appeared after Elizabeth's death. Nonetheless, the new Protestant ingredient

in English identity (God's 'elect nation') also undermined acceptance as Englishmen of Ireland's

Catholic Old English.

New initiatives

Elizabethan policy towards Ireland was predominantly reactive, but there were also some new

initiatives to extend English rule. Perhaps the most successful was the establishment in Connaught

and Munster in 1569-70 of regional councils (or presidencies), along the lines of those in Wales

and the English north. Initially, their intrusion antagonised local magnates, particularly in Munster

where the earl of Desmond's cousin, James Fitzmaurice, tried to whip up Catholic opposition and

appealed unsuccessfully for Spanish support. Later, however, the councils became self-financing

through the device of composition.

Composition involved, in Gaelic parts, the commutation of the chief's right to take up supplies for

his household and quarter his kerne and galloglass on his subjects for defence. This practice,

known as coign and livery, had also spread to outlying English parts. Its English equivalent,

purveyance for the army and governor's household, was also commuted, so reducing the queen's

overall charges but generating fierce resentment in the Pale where it was seen as a new,

unconstitutional, system of military taxation, levied without the subject's consent.

'...the theory and practice of English government in Elizabethan Ireland diverged alarmingly.'

Even more disruptive were the experiments at colonisation, notably in east Ulster (in 1572-3), and

the Munster plantation from 1584 which smacked of ethnic cleansing. Originally, Gaelic chiefs

like MacMurrough Kavanagh had tolerated small colonies of Englishmen on ex-monastic land to

guard harbours and fords and civilise the natives. Yet, as with the army, the government had the

greatest difficulty in controlling would-be conquistadores. English captains and colonists like

Humphrey Gilbert and Walter Raleigh were less interested in teaching the natives the benefits of

English civility than in making their fortunes by goading them into hopeless rebellion and then

grabbing their land. Accordingly, the theory and practice of English government in Elizabethan

Ireland diverged alarmingly. The queen and council in England aimed gradually to strengthen

Tudor rule by making English law and local government more widely available and treating

Gaelic chiefs and Old English lords as good subjects. English captains on the ground, often with

Dublin's collusion, preferred a military solution, keeping the country under martial law to crush

opposition and extend English rule by force.

Responses to conquest

The result was a gradual escalation of violence and atrocities, particularly from 1579 when

originally distinct strands of dissent - religious and political, Gaelic and Old English - began to

coalesce. The Desmond rebellion in Munster (1579-83), for instance, coincided with an Old

English Catholic rising in the Pale led by Viscount Baltinglass, supported by Gaelic chiefs,

notably Feagh MacHugh O'Byrne; a further Pale conspiracy; and two minor landings of Italian

and Spanish troops. The risings were brutally suppressed, with massive military reinforcements

from England, and Munster was left a wasteland.

The Ulster confederacy led by Hugh O'Neill, earl of Tyrone, during the Nine Years War

(1594-1603) was even more serious. His faith-and-fatherland nationalism attracted little overt Old

English support, but Tyrone assembled a modern army capable of matching Elizabeth's army in

the field. Following the English defeat at the Yellow Ford (1598), revolt spread to Connaught and

Munster, and a Spanish landing of 4,000 troops at Kinsale (1601) left the issue very much in doubt.

With Elizabeth facing bankruptcy, 'harp groats' reappeared to pay the army, in which 19 per cent

of England's available manpower was eventually committed. The War eventually cost Elizabeth c.

£2 million.

' The risings were brutally suppressed, with massive military reinforcements from England...'

Elizabeth thus paid a heavy price for her parsimonious and irresolute approach to Irish affairs and

her inability to exercise effective control over her ministers there. Ireland was pacified, though

partly destroyed, and the manner of the conquest united Gaelic and Old English in new forms of

Irish Catholic nationalism (v. both the Protestant New English and Scottish Gaeldom).

Paradoxically, English rule now enjoyed less indigenous support than in 1558 and depended

heavily on financial and military support from England.

Find out more

Books

Ireland in the Age of the Tudors by Prof Steven Ellis, Addison Wesley Longman Ltd (London,

1998)

Elizabeth's Irish Wars by C. Falls (Constable and Co. 1996)

Oxford Illustrated History of Ireland edited by R.F. Foster (Oxford University Press, 1989)

About the author

Professor Steven Ellis is a Tudor specialist, teaching history through both English and Gaelic at

the National University of Ireland, Galway. His many works on English, Irish, and British history

include the standard survey of Tudor Ireland, Ireland in the age of the Tudors (Addison Wesley

Longman Ltd, London 1998).