Money and Politics recov

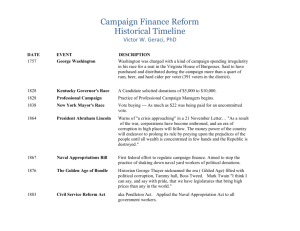

advertisement

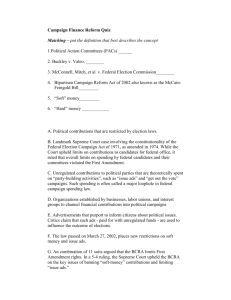

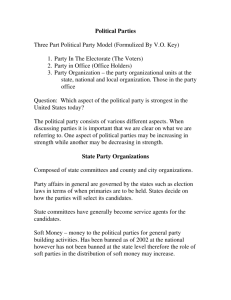

Money and Politics How much money do Americans spend on political campaigns? Do wealthy contributors “buy” government influence? Should the government limit campaign contributions and spending? Important Background Information: 1st Amendment: Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances. Political Action Committees (PACs): Organizations established by businesses, labor unions, and interest groups to channel financial contributions into political campaigns. Buckley v. Valeo, 1976: Landmark Supreme Court case involving the constitutionality of the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971, as amended in 1974. While the Court upheld limits on contributions to candidates for federal office, it ruled that overall limits on spending by federal candidates and their committees violated the First Amendment "Hard" Money: Political contributions that are restricted by election laws. "Soft" Money: Unregulated contributions to political parties that are theoretically spent on "party-building activities", such as "issue ads" and "get out the vote" campaigns. Such spending is often called a major loophole in federal campaign spending law . Issue Ads: Advertisements that purport to inform citizens about political issues. Critics claim that such ads - paid for with unregulated funds - are used to influence the outcome of elections. Public Financing of Presidential Campaigns: Under the 1974 amendments to the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971, presidential candidates can receive government subsidies if they accept spending limits. Currently, they can obtain as much as $18.6 million in public subsidies for their campaign through the nominating conventions. In return, they must agree to a $45 million spending limit during that period as well as caps in individual states. For the general election, party nominees receive about $75 million in public money. During the 2004 election campaign, President Bush and Democratic candidates Howard Dean and John Kerry refused to accept public funding for the presidential primary campaigns so that they could raise more money than the rules permit. Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002 (BCRA), Public Law 107-155, also known as the McCain-Feingold Bill: The law, passed on March 27, 2002, places new restrictions on soft money and issue ads McConnell, Mitch, et al. v. Federal Election Commission, 2003: An amalgamation of 11 suits argued that the BCRA limits First Amendment rights. In a 5-4 ruling, the Supreme Court upheld the BCRA on the key issues of banning "softmoney" contributions and limiting "issue ads." Citizen’s United v. FEC Overruling two important precedents about the First Amendment rights of corporations, a bitterly divided Supreme Court ruled that the government may not ban political spending by corporations in candidate elections. The 5-to-4 decision was a vindication, the majority said, of the First Amendment’s most basic free speech principle — that the government has no business regulating political speech. The dissenters said that allowing corporate money to flood the political marketplace would corrupt democracy. The ruling, Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, No. 08-205, overruled two precedents: Austin v. Michigan Chamber of Commerce, a 1990 decision that upheld restrictions on corporate spending to support or oppose political candidates, and McConnell v. Federal Election Commission (NY Times, 1/21/2010) Money and Politics 1. How much money do Americans spend on political campaigns? According to the Center for Responsive Politics, a tight race for the House of Representatives cost approximately $1.5 million to $2 million in 2000. The average cost was $840,000. Huge spending in New Jersey and New York in 2000 raised the average cost of a Senate seat to $7.3 million. A study by Common Cause reveals that before the Bipartisan Campaign Finance Reform Act took effect on November 6, 2002, the Democratic and Republican Parties raised a recordbreaking $470.6 million in soft money during the 2001-2002 election cycle. In the 2000 cycle, Democrats raised $219,343,172 in soft money, while Republicans collected $243,780,583 in unregulated funds. 2012 to date: Candidate Obama Romney Gingrich Paul Santorum Total Contributions (approx.) % Small Donors $140 million 47% $63 million 10% $18 million 48% $30 million 47% $7 million 49% All House All Senate Dianne Feinstein Darrell Issa $399 million $237 million $2.8 million $1.1 million SuperPACs – Independent Expenditure Only Committees -- $51 million Sources: Federal Election Commission http://www.fec.gov/disclosure.shtml OpenSecrets—Center for Responsive Politics http://www.opensecrets.org/elections/index.php What are the effects of these costly political campaigns on the democratic process? Money and Politics 2. Do wealthy contributors “buy” government influence? Less than 1 percent of American voters give contributions of $200 or more to candidates. Roughly one-tenth of one percent gives $1,000 or more to a candidate for federal office, a political party, or a political action committee Homework: Visit this website: http://www.pbs.org/now/politics/cfmemos.html PBS “NOW” Politics and Economy: What Money Buys. Read your assigned document and write a brief summary of it. (Who is involved in the communication? What type of communication is it? How does the campaign contributor hope to influence government? What is the campaign offering? How successful was the attempt?) Money and Politics cont’d. 3. Should the government limit campaign contributions and spending? Arguments in favor of limits: Arguments opposed to limits: