Child Labor In The Industrial Revolution

advertisement

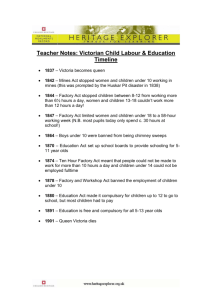

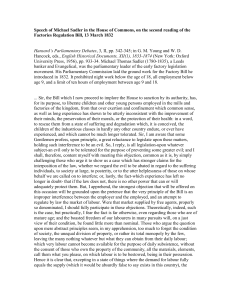

1 Child Labor In The Industrial Revolution Dr. Linda Karen Miller Fairfax High School, VA The Industrial Revolution had an enormous and deplorable effect on children and family life. During the 19th century, children worked in various industries such as textile mills, foundries or coal mines. Wages, often essential for the family’s survival, varied. The jobs involved physically hard work and were dangerous. Wages in coal mines were high but children always received less than men. Some work involved long hours and poor working conditions affecting people’s health and ability to work. Children as young as five or six could easily be trained to do many of the simpler tasks. Labor wants of 2 factory owners were also supplied by pauper children sent through workhouses around the country. The children lacking families, were maltreated in the factory. If some died because of harsh treatment they could easily be replaced by others in “apprentice” houses. My interest in this topic has been long standing as I have played the character of Elizabeth Bentley of Leeds, England who testified before Michael Sadler’s Parliamentary commission in 1832 investigating factory conditions. I have also used a slide from the 1840 book entitled “Michael Armstrong Factory Boy” showing poor factory children eating from a pig’s trough. With this background in hand, I was surprised to read that some of the “historians” we read doubted the validity of the Sadler Report. I thus started my own investigation. I used Parliamentary Papers and debates and primary sources from various historical spots. My investigation revealed the following insights. The consciences of a few humane men were being awakened and the reports of commissions of 1832, 1842 and 1862 did much to bring the stark facts to light and led eventually to a gradual improvement in working conditions. Sadler lost no time in bringing the subject before the House of Commons and obtained the appointment of a parliamentary committee of inquiry. In investigation the primary sources I found out the following. For the Sadler Report Elizabeth Bentley was questioned on June 4, 1832, She was 23 at the time. She had been employed in the flax mill where she worked from 5 AM until 9 PM cleaning and changing the frames. She worked from the age of six. Children were beaten if they were too slow. Later if she went to another mill where she moved heavy baskets and dislocated her shoulders ( I saw the baskets at one of the mills and could understand why this happened). Many people got sick from the dust. The work caused Elizabeth to become bent over from the age of thirteen. She ended up in the poor house because she couldn’t work. Various statistical information support her claims and others all over England. From 1813-33 in the county of Derby, there were 1, 927 deaths of children under 9 in 20 years. There were several medical reports such as the one from Dr. Kirkland who said that the spinning room was wet and filthy. There was always a disagreeable odor. There 3 was also little time for education. The employers were asked a series of 35 questions by the Children’s commission which included such questions as ventilation and danger of machines but the answers were far from truthful. So one of the historian’s accusations that the Sadler report was invalid because it did not interview the factory owners was far from truthful. However conditions at home were not much better. Most of the working class lived in “back to back” housing. Some had their bedroom over the “outhouses” which were only emptied once a week. Working mothers added to the problems by administering laudanum to keep their infants quiet. Many infants died. The mills were not the only problems. There was much child labor regarding chimney sweeps and the mines also had problems. The high accident rate in the mines especially in the Black Country led to the mining commission and laws to improve safety. The mines were not regulated until 1872 in Wales. During the testimony of the commission December elections supervened and Sadler was defeated by the youthful Macalay. When he lost his seat in 1832, Anthony Ashley Cooper (who became the 7th Earl of Shaftsbury in 1851) assumed Parliamentary leadership. When finally passed, the Act of 1833 was the first to be enforced because it appointed inpectors, forbade the employment of children under 9 at any time and persons under 18 at night and a maximum of 9-12 hours a day. However many industries were not covered by this act and in 1840 another commission was appointed for further investigation. Lord Ashley reasserted to prevent all children under 18 from working underground. However, members of Parliament such as Lord Londonberry, a powerful coal miner, fought against the change. The result was the 1842 Employment Act which prohibited all women but allowed children under ten in the mines. The ten hours bill finally passed in 1847. Further laws were needed in 185053 to make ten hours a reality. The lace factories were not regulated until 1861. Sweeping extensions followed in 1867. Although the real object of the bill was the protection of adults, it was very unsuccessful in providing for the protection of children. The ten hour day was too much for a child of ten. Lord Ashley’s bill did not concern itself with the use which the child worker should make of this hours of leisure when his work was done. The commissioners 4 proposed that every child employed in a factory should be compelled to attend a schoool and the bill finally passed provided that the children whose work was restricted to 48 hours a week must attend school for two hours every working day. However the State provided no funds. This was left up to manufacturers,. However even with these various acts over a number of years, the abuse continued. The law was obeyed in some areas but not in others. In 1873 Lord Shaftsbury after a long life spent in public service, drew attention in the House of Lords to an investigation of a climbing boy 7 ½ years of age who had suffocated on a flue in the county of Durham. Lord Ashley said that the condition of factory children was 10 times better than that of chimney sweeps. “After years of oppression and cruelty, death has given me the power of one more appeal.” A bill introduced in 1875 but Shaftsbury brought these scandals to an end. No chimney sweeps could carry on his trade without a license from the police. If there was any doubt about the validity of the Sadler and other commission reports, one should visit the Black Country living museum. There you can experience first had the conditions in the mines and in the iron works factories. Also Corry Bank Mill gives another useful insight. I am sure it will make everyone glad that they got a college education. Now with all of this documentary evidence, I thought how best to get it across to the students. I decided to do a documentary based essay question (DBQ) and then later I hope to expand it into a documentary teaching unit which I will present to the National Center for History in the Schools which I hope they will publish. 5 DOCUMENT BASED ESSAY DIRECTIONS: The following question is based on the accompanying Documents. (Some of the documents have been edited for the purpose of this exercise.) This question is designed to test your ability to work with historical documents. As you analyze the documents, take into account both the sources of documents and the authors’ point of view. Write an essay on the following topic that integrates your analysis of the documents. Do not simply summarize the documents individually. You may refer to relevant historical facts and developments not mentioned in the documents. Was the regulation of child labor necessary? Historians support both views. Based on the following documents, discuss the political, social and economic effects of regulating child labor. What kinds of additional documentation would help assess the impact of regulation on the factory system? DOCUMENT 1 SOURCE: Reprinted from Women, Work and the Industrial Revolution 1750-1850 by Ivy Pinchbeck 1930. The 1843 Report of the Children’s Employment Commission states: “One of the most appalling features connected with the extreme reduction that has taken place in the wages of lace runners, and the consequent long hours of labor is that married women having no time to attend to their families or even to suckle their offspring, freely administer opium in some form or other to their infants, in order to prevent their cries interfering with the protracted labor by which they obtain miserable subsistence. ..The result is that a great number of infants perish. Those who escape with life become pale and sickly children, often half idiotic, and always with a ruined constitution. DOCUMENT 2 SOURCE: Parliamentary Debates Vol IX London Hansard 1832, House of Commons February 1, 1832 6 Mr. Sadler presented a petition from ten thousand operatives of Leeds chiefly employed in factories praying to adopt some means for limiting the duration of labor of children employed in the factories…The petitions witnessed the sufferings and cruelties practiced upon the unhappy and miserable children who were subjected for sometimes even thirty hours successively in an overheated and most atmosphere without any relaxation… DOCUMENT 3 SOURCE: Parliamentary Debates Voil X London Hansard 1832, House of Lords Debate March 1, 1832 The Archbishop of Canterbury presented a petition from the inhabitants of Rochester to support the proper regulation and limitation of the hours of labor for children…that it was attended with the most serious injury to their morals; it was a disgrace to a Christian and civilized community to allow putting money in the pockets of master manufacters… DOCUMENT 4 SOURCE: British Parliamentary Papers Children’s Commission 1832 Vol. 4 , p. 8 In the Western District, Mr. Rice of Painwick, Glocestershire, woollen manufacturer: “We have no objection to the restriction of children from work until they are nine years of age, provided the legislature will adopt means for the maintenance and education of such children; and a limitation of hours for those from nine to fourteen years of age, and after fourteen years of age to be allowed to work to the advantage of themselves and at the convenience of their employers.” DOCUMENT 5 SOURCE: British Parliamentary Papers Vol. 9 p. 11 In Nottingham it appears that Children begin to work at this employment as early as five years of age. Jonathan Barber, forty years old: Is a mechanic employed in stocking and silk glove making. In the hosiery and lace trade the children begin to work at five years old. Six of the witness’s children began about five years of age. 7 DOCUMENT 6 SOURCE: Children’s Commission Report 1862 p. 32 Thomas Roebuck, fork-grinder at Askham’s wheel. Began fork grinding when I was 10 years old and have been at it for 28 years. I had two boys, but I told their parents they had better take them away and I have none now. If they begin young they go off like dyke water, so quick. I know one that began at 8 years old. He was quite fresh up to 17 and died at 19. His lungs were completely gone with the grinder’s complaint. Sometimes a stone flies out. This is very dangerous if it is a boy at work because he has not sense to get out of the way. DOCUMENT 7 SOURCE: Report of John Leigh 1849, member of Manchester Salford Sanitary Association No, 3 Thomas Cavanagh, age 5..Constitution a very fine healthy child. Natural susceptibility, not ascertained. Predisposing cause, half starved. Localty, crowding, fifth. No source of contagion. DOCUMENT 8 SOURCE: 1847 Commission report No. 206 Fanny Drake aged 15. May 9. I have been 6 years last September in a pit. I hurry by myself. It has been a very wet pit and I have to hurry up to the calves of my legs in water. I go down at 7 and come out at 5. 8 BIBLIOGRAPHY Blincoe, Robert. Memoir, Sussex, Caliban Books, 1977. Douglas, David, Ed. English Historical Documents, p. 251, 949, 967. Giffen, Robert. The Progress of the Working Class in the Last Half Century, London George Bell and Sons, 1881. Halevy, Epie, A History of the English People 1830-41, London, Fisher University 1927. Iliffe, Richard. Victorian Nottingham, A Story in Pictures, Vol. 17, Nottingham Historical Files, Derby and Sons. Hansard, T. C. Hansard Parliamentary Debates Vol. IX-X, London 1832. Parliamentary Papers, Children Employment Commission 1832, Reprinted by Irish University Press, 1842, p. 95-97, 196-99. Spicer, Suzanne. Victorians at Work, education department Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust Ironbridge, Telford Shopshire. Victorian Workers, National Coal Mining Museum, 1997.