Balancing the Teaching of Grammar in The

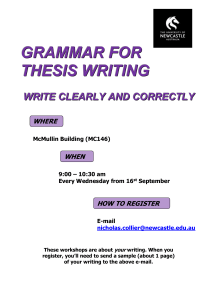

advertisement

Beth Pilawski Traditional Instruction vs. Whole Language: Balancing the Teaching of Grammar in The Current Age of Standardized Assessment The teaching of grammar is a pedagogical subject that has been surrounded by debate. The form by which grammar is taught has changed many times over the course of the last hundred years, most notably from strict diagramming techniques and memorization to a “whole language” approach. There are numerous studies, articles and even associations in support of both styles. In order to gain the most accurate assessment of each method, I read about, observed and practiced both methods during my student teaching. My research and observation helped to lend some personal insight into tackling the dilemma of which of the two styles is most beneficial to the development of concise student writing, and how this development relates to the standardized exam. There is certainly no prescribed consensus among educators as to which method is more beneficial, nor are there any prescribed guidelines on how to successfully use either method in the classroom. Even the national standards for teaching grammar are rather vague. The most pertinent include: 1. Students apply a wide range of strategies to comprehend, interpret, evaluate, and appreciate texts. They draw on their prior experience, their interactions with other readers and writers, their knowledge of word meaning and of other texts, their word identification strategies, and their understanding of textual features (e.g., sound-letter correspondence, sentence structure, context, graphics) (Standards for the English Language Arts, December 1, 2004). 3. Students adjust their use of spoken, written, and visual language (e.g. conventions, style, vocabulary) to communicate effectively with a variety of audiences and for different purposes (Standards for the English Language Arts, December 1, 2004). 6. Students apply knowledge of language structure, language conventions (e.g., spelling and punctuation), media techniques, figurative language, and genre to create, critique, and discuss print and non-print texts (Standards for the English Language Arts, December 1, 2004). While most schools and standards (including the above) are quick to state the final goals for grammar and writing instruction, most neglect to formulate an opinion on the best way for an educator to achieve these goals. It is important to have a grasp on the definition of each of the two methods in order to understand the educational dialogue that surrounds them. The whole language approach can be challenging to understand because it is a fluid approach that is personally tailored by each educator that uses it. Despite this inconsistency, there are some basic principals that most practitioners of the approach follow. Essentially, these ideas culminate in the belief that students should be encouraged to focus on the meaning of what they are writing as opposed to the formal grammatical and syntactical formations of the sentences. It is assumed that the correct grammatical and syntactical formations will be gleaned from everyday reading and conversation. The actual methods for teaching in a whole language approach vary widely. There is no consensus as to how to teach or any prescribed curriculum in a whole language environment. Teacher and author Janet Allen offers the following observations the lack of a consensus regarding the whole language approach in her book, It’s Never Too Late: I had to agree with Goodman (1986a), “Whole language is clearly a lot of things to a lot of people” (p 5). Isolated standardized testing programs and controlled reading had no place in my definition of the philosophy of whole language. On the other hand, I wasn’t sure what was happening in my classroom would fit my understanding of whole language either (23). Formal grammar instruction, on the other hand, follows a very prescribed course of study. This includes the introduction of phonics in elementary school and the implementation of more specific methods of grammar instruction during middle and high school. These methods include, but are not limited to, lessons such as repetitive practice, diagramming sentences and rote memorization. Heavy emphasis is given to skills such as recognizing specific grammatical conventions in context, recognizing sentence types and identifying the correct usage of various types of words in sentences. The research regarding the effectiveness of the two approaches varies widely. Most seems to support the idea that the two methods should be used to complement each other, especially in today’s world of standardized testing. Though this may sound good in theory, the idea is not without conflict. Tracy David Terrell, professor of linguistics at the University of California, offers these observations on the gap between possessing a formal knowledge of grammatical conventions and the ability to utilize this knowledge in everyday speech and writing: An explicit knowledge of grammar by adults is said to be useful in only one way—as a “monitor” for self-correction under certain circumstances, to wit, that the learner “know the rule” to be applied, that the learner be focused on correctness, and that the learner have time to think about applying the rule to the output (52). This observation is interesting when considering the current focus on formal grammatical knowledge. It would appear that rote memorization of grammatical conventions has not been proven to assist with the fluency of writing and speaking, and yet the focus is shifting back to its formal instruction in the classroom. Jim Burke, author of The English Teachers Companion concedes, States throughout the country now have curriculum standards and frameworks that call for a renewed emphasis on the teaching of grammar…at all grade levels. This demand stems from a frustration in the workplace and college writing programs students’ lack of grammatical correctness…(125). Clearly there is a need for strong writers and speakers in all aspects of our society. Yet if the formal instruction of grammar has little to no affect on the development of students’ writing, one must question why our society places so much value on it by including it on standardized tests. My student teaching observations introduced me to a combination of the two methods of instruction, and also to the affect that standardized testing is having on current methods of grammar instruction. While placed in a ninth grade gifted and honors classroom, I observed a teacher who assumed that grammar instruction should have occurred prior to her student’s arrival in her classroom. Though the teacher did include an occasional formal grammar lesson, these were to be considered “reviews” of previously gained knowledge. Most of these lessons consisted of having the students review the conventions of one particular part of grammar (adverbs, for example), and then participate in an out-loud reading of the exercises at the end of the chapter. The immense gap of the abilities of the students in the class was immediately evident upon observing the first few exercises. Some of the students were able to go through the exercises with ease, while others squirmed uncomfortably in their chairs as it came closer to being their turn. It was almost painful to watch some of the students struggle to find the right answer to their assigned question. Interestingly, these were also the students that had a more difficult time with the writing assignments, and their other classroom assignments as a whole. Most could barely form paragraphs, let alone focus on using more mature organizational strategies and descriptive language. However, despite these obvious discrepancies in performance, it was very difficult to assess where each individual student was on the road of language and writing development. The students that struggled with their grammar exercises and other assignments were also normally the ones who had difficult home lives or had moved around a great deal as a child. Was their poor performance due to a lack of knowledge of grammatical conventions, or a lack of a stable educational base and immersion in reading? The answer to this question remained elusive. My high school cooperating teacher often questioned the placement of these students in an honors level class, but nonetheless worked with them after school to maintain their grades and become more familiar with the formal grammatical conventions of writing. One interesting thing I noted was that the grading of these students was different than the rest of the class. The rubrics conceived for these students were loosely based on the whole language concept of placing emphasis on comprehension and meaning as opposed to syntax and other formal structuring. In this particular application, the whole language route was also seen as the “lower ability” route. Students with a formal knowledge of grammar were considered to be the students of a higher ability level, a standard clearly reflective of standardized testing. Another quality that many of these students possessed was the fact that they had not attended the adjoining middle school. This high school had the unusual situation of having a large percentage of their students (more than eighty-five percent) filter in from the neighboring middle school. This allowed for the direct collaboration between teachers of all grades regarding the teaching of writing. Unfortunately, this arrangement put those students who did not attend the middle school at a distinct disadvantage. They were clearly less prepared to meet the demands of the high school teachers. My middle school cooperating teacher had similar ideas about the instruction of grammar in her classroom. All of her students could identify grammatical conventions when called on in class, and I never observed an awkward moment where a student struggled with a grammar question. Her approach to teaching grammar was more along the lines of the traditional diagramming and memorization, and she carefully followed a prescribed method each day. Utilizing a workbook, she listed one sentence on the dryerase board each week. Monday, the students worked on parts of speech, Tuesday: sentence parts, Wednesday: clauses and sentence type, Thursday: punctuation and capitalization and Friday: diagramming the sentence. When asked how she felt about this structured method of instruction, she replied, “I’m not sure that formal grammar instruction improves the kids’ writing overall, but they are tested on it. Most of these kids could pick up these conventions by listening to those around them” (Conversation, November 29, 2004). I found this statement to be indicative of the current trends in grammar instruction. According to Research on Written Composition, New Directions for Teaching, which quotes a 1963 study by Braddock, Lloyd-Jones and Schoer, “in view of the widespread agreement of research studies based upon the many types of students and teachers…the teaching of formal grammar has a negligible…effect on the improvement of writing” (133). It appears as though even though research has shown that the formal instruction of grammar has little to no affect on the quality of student’s writing, it is included in instruction because standardized tests demand it. If one directly sites the research available, putting students through hours of rote memorization and filling out worksheets in order to recognize the formal conventions of grammar seems unnecessary. This opinion is supported by research such as that of Leona B. LeBlanc, in her article “A Comparison of Instructor-Mediated versus StudentMediated Explicit Language Instruction in the Communicative Classroom”: “students who acquire grammar inductively through implicit instruction would learn grammar as well as students who were taught deductively (explicit instruction)” (736). This “explicit instruction” can be reached through use of music and video, illustration and other creative outlets can help to keep kids’ attention and accomplish the true goal of ensuring that students are internalizing what you are teaching them, and not just blankly memorizing a list of definitions. Teacher and author James Burke offers the following motivation for students attempting this “mixed” approach of grammar instruction: If, however, students learn elements of grammar in the context of expanding their options as writers, it has its place…When my students come in, I tell them we will focus on how to make their writing more descriptive and their sentences stronger (125). Findings such as these draws into question the value of memorizing and internalizing the various formal constructions of grammar. This especially since students must then make the next step of applying that knowledge with little or no assistance from their instructors. It has been my experience that while most educators are quick to assist their students in the identification of grammatical conventions through grammar practice, few take the next step of helping their students identify them in their own writing. This potential gap in the instructional process obviously supports the previously mentioned research. It was with this research and personal experience in mind that I approached my first-period middle school eighth graders with a challenge. While opinions on both sides of the controversy vary, I wanted to conduct a small, short-term study to see if I could determine which blend of the two methods might better help my students. I acknowledge that this study is limited in subject size and scope, but I felt that with its completion I could gain a basic insight into what might work best for my students. To begin, I presented my twenty-six students with a one-page, four-paragraph essay that was full of grammatical errors. The task was to edit the essay, and to break up the monotony I had them complete the first two paragraphs on their own and save the last two to go over with the class. The results were pretty much what I expected. The students who were already reasonably proficient in reading and writing did fairly well with the editing, while my ESOL (English as a second language students) and those on the lower end of the curve did not see many of the errors. I then asked the students to name the grammatical rule that was broken in each of the incorrect sentences. This too went as I expected. The students named only one or two of the more commonly known rules. These results confirmed my suspicions that most of the students from a reasonably stable educational background in English will be able to pick out and edit a grammatically incorrect sentence, but usually will not know which of the formal grammatical rules or conventions are being broken by the sentence. This would be just fine for those in support of a whole-language approach, but is unacceptable in the face of the thirty-five standardized tests that my students take in one school year’s time. Standardized testing is clearly beginning to dictate which method of instruction that today’s educators are using. Though it seems to go against research, all teachers must include the formal instruction of grammar in the classroom in order to prepare their students for standardized testing. Despite this, my personal methodology clings to the idea that educators should make an effort to strike a balance between the two methods. I believe that success lies in area between rote memorization of grammar skills and the application of those skills to everyday writing and speaking. Both methods of grammar instruction place value on the final goal of instruction, which is to produce concise, creative writers. Therefore, creating harmony between the two should be the focus of English teachers who are committed to producing wellrounded and knowledgeable students. There is no exact answer to the question of which method of instruction is best. Truthfully, it seems to depend on what the person assessing the writing values more: meaning or correctness. Being mindful of this and of the weight of standardized testing, teachers must focus on keeping the student’s attention and on helping them to process and store what they need to learn. The key seems to be to devote time to finding a balance between the two methods and carefully pre-assessing each student to get a background of what they have learned and what they need to focus on. The collection of this information is vital to the responsible planning of classroom grammar activities that will appeal to and best instruct all types of learners. Works Cited Allen, Janet. It’s Never Too Late. Portsmouth, New Hampshire: Heinemann, 1995. Burke, Jim. The English Teacher’s Companion. Portsmouth, New Hampshire: Heinemann, 1999. Hillcocks, Jr. G. Research on Written Composition: New Directions for Teaching. Urbana, Illinois: ERIC Clearinghouse on Reading and Communication Skills, 1986. LeBlanc, L.B. & C.G. Lally. “A Comparison of Instructor-Mediated versus StudentMediated Explicit Language Instruction in the Communicative Classroom.” The French Review, 71, (1998): 734-746. Standards for the English Language Arts. 1 February 2005 <www.ncte.org/standards>. Terrell, T.D. “The Role of Grammar Instruction in a Communicative Approach.” The Modern Language Journal, 75, (1991): 52-63.