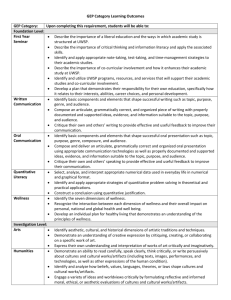

How can we interpret feminine imagery in Pre

advertisement

How can we interpret feminine imagery in Pre-Columbian Art from the southern part of the Central Andes, 800 BC-1500 AD? Bat-ami Artzi Doctoral student in the department of Romance and Latin American Studies with presidential scholarship of the program for excellent students in the Faculty of Humanity. Adviser: Prof. Jan Szemiński The subject of this investigation is the feminine image as it is represented on artifacts, mainly ceramics and textiles, which were produced by pre-Columbian cultures from the southern part of the Central Andes,1 800 BC-1500 AD. The aim of this investigation is to reconstruct the role of the woman in these societies as well as to broaden our understanding of the concept of sexuality in these cultures. The investigation will test whether this kind of reconstruction is possible and to what degree. Due to the lack of historical written sources, archaeological and iconographical studies—with the assistance of anthropological, ethno-historical and linguistics research—are the only way to reconstruct the role of females in these cultures. The geographical and chronological definition of this investigation includes the centers of the first expanded states and the first empire of the central Andes (Tiwanaku, Huari and Inca). This allows me to observe evolutions of the ideas that these cultures had concerning the role of the woman and femininity. The archaeological and iconographic studies involving gender mainly focus on the north coast of Peru, especially on the Moche (Hoquenghem & Lyon 1980; Benson 1988; Catillo & Holmquist 2000; Cordy-Collins 2001, 2001a), but also the Chimu (Mackey 2001), the Lambayeque (Cordy-Collins 2001) and, in the northern highland, the Recuay (Gero 1992, 1999). Nevertheless this area received little attention in anthropological and ethnographic studies. 1 An area that includes the northern parts of Chile and Bolivia and the southern and central part of Peru. The southern part of the central Andes, in contrast, has been studied extensively by ethnographers and anthropologists, but there are few iconographic studies on gender. One exception is Lyon’s (1978: 108) study, which dealt with the female supernatural figures of Paracas, Yaya-mama, Nasca, Pachacamac and Huari (but not the Tiwanaku), among other cultures. The combination of disciplines such as ethno-history, archaeology, history of art, anthropology and ethnography is vital to the study of the Andean region; therefore this investigation will try to fill this absence of gender iconographic studies in the southern parts of the Central Andes. The extensive anthropological, ethnographic and ethno-historic studies of this region can be used to interpret the iconography of the cultures of the area. The chronological frame of this investigation (800 BC-1500 AD) was also chosen deliberately to fill a gap in the gender iconography studies, since the ethno-historical studies dealing with gender focus on the later Inca-dominated period (Silverblatt 1976, 1987, 1991; and Rostworowski 2007). Gender studies based on iconography in previous periods, as well as contemporary cultures in other areas, focus on Chavin (Cordy-Collins 1976, 1983), Moche (Hoquenghem & Lyon 1980; Benson 1988; Catillo & Holmquist 2000; Cordy-Collins 2001, 2001a) and Recuay (Gero 1992, 1999). The investigation is based on artifacts—mainly ceramics and textiles—from the cultures within the chronological and geographical frame that contain feminine images. The study compile a database that includes artifacts from museums and collections, as well as artifacts found in archaeological excavations. Before focusing on selected items the research delve into the iconography of the cultures in question and determine the components that identify the figure as feminine. The feminine images that are represented in these artifacts contain a message that may be read with careful examination, comparison and interpretation, assisted by complementary disciplines. According to semiotic theories, the work of art is created on basis of the community consciousness and served as an autonomous sign; it might also serve an informational function (Mukařovsky 1984: 9). Basing on these postulations we can assume that the artifacts analyzed under this study were created based on the community consciousness; in this case, the consciousness may be local (that of a specific culture) or supra-local (a pan-Andean consciousness). In accordance with the semiotic theories, the specific artifacts under investigation served as signs, and in most cases had informational functions as well. Consequently, we can refer to a group of artifacts as containing a common basis, as well as pose questions about the signs they represent and the information and messages they contain. Beyond the broad theories discussed above, the basic question underlying this investigation asks what kinds of women are depicted on the artifacts: Goddesses? Priests? Ancient mothers? Mythical figures? Nobles? Simple figures occupied with daily activities? Inevitably, this investigation will take into account the social contexts of the women that are depicted on the artifacts. Each of these represented women acted in a social context, whether in the real world or the mythic world. In addition, the investigation will examine whether there are similarities or differences between the cultures in question, and whether there is continuity or development of the female imagery through time. The image interpretation will be supported by ethno-historical, ethnographic, anthropological and archaeological studies that might illuminate the meanings of some components of the images. Linguistic studies provide another source of information: early colonial Quechua and Aymara dictionaries show specific words as referring exclusively to women and their activities. This gender-specific terminology might contribute to my understanding of the feminine role in the societies that spoke—and continue to speak—these languages. In the last stage of the investigation, the investigation will compare the feminine images from this study to those of other Andean cultures and other ancient world cultures. This comparison will raise questions in several contexts: the context of the specific periods under consideration, the context of Andean civilization more generally, and the context of gender as perceived in other civilizations. The first context refers to the role of the woman in these cultures: what kinds of women are represented in these artifacts? Mythical or real women? To what group and status did they belonged? Are they represented performing activities of daily life and work? The questions about the Andean context will deal with similarity or differences in the way that those cultures capture the feminine image. It seems that there is a different physical emphasis in the Andean depiction of women (for example compared to the famous European image, “Venus of Willendrof”). Therefore, the third level questions ask if these differences are due to true differences in female anatomy, differences in the Andean concepts of sexuality, or perhaps a combination of the two.