Wearing Virtue on Her Sleeves: Fabric and Fashion in the Lays of

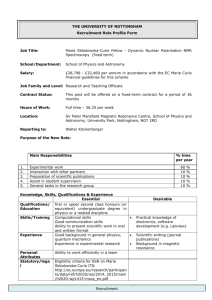

advertisement

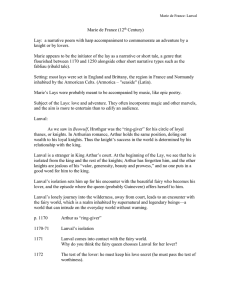

Wearing Virtue on Her Sleeves: Fabric and Fashion in the Lays of Marie de France Marie de France’s lifetime marked the advent of fashion as we know it. She and her contemporaries, Chretien de Troyes and Beroul, brought the lavish, lengthy costume descriptions into vogue in 12th century French romance. Marie was intensely concerned with the intimate details of her characters’ clothing, and such loving detail was not just for texture; Marie de France’s choices of fabrics and fashion offer glimpses into character development and thematic elements. In the words of Monica Wright: “Clothing in the romance of the period became part of the weave of the text, appearing and disappearing at intervals, like a thread in a tapestry, structuring as it embellishes” (8). To overlook or devalue the clothing and textiles Marie weaves into her narrative would be to discard critical information in the development of her characters and their world. While Marie’s Lays took place in a fantastic version of medieval France, she was meticulously true to life in her choices of fabric for her characters’ costumes. Her female characters in particular are accurate to noble fashions of the time. The lovers of Lanval and Gugemar, for example, are both said to wear figure-hugging dresses; the 12th century is the first time in the history of women’s fashion that clothes were tightly fitted (Smith 96). The symbolism of the previously scandalous tight dress will be discussed later; for now we will turn our attention to the more objective aspects of Marie’s writing. In the Lay of Lanval, Marie uses fabric choice to communicate the mysterious Lady’s extravagant wealth. Silk, the material most often associated with lavish wealth, was formerly so costly and precious that is was reserved exclusively for religious purposes (Piponnier 19). The Lady is so wealthy, even her servants wear fine silks (Burgess 1773). However, it is not just the chosen textile that illustrates the Lady’s riches, but the colors as well. The richest, darkest dyes in the 12th century were within the grasp only of the most well-to-do nobles. (Piponnier 16-17), and the Lady and her servants appear wearing precious silks of deepest purple (Burgess 1769, 1773 and Mason 74). Only the Lady, however, is garbed in an ermine-lined cape, a distinctly feminine material and among the costliest of furs (Piponnier 24, 79). Arthur and his court marvel at such well-dressed women. In another lay, the Lay of the Ash Tree, such inestimably valuable fabrics appear again as narrative devices. A noble lady is forced by circumstance to abandon her newborn daughter, but leaves a letter, a ring, and a strip of fine samite so that whoever takes her in will know of her noble birth. This single piece of scarlet fabric is, by its description, perhaps the most lavishly precious textile in Marie de France’s work. Red was by far the rarest and most expensive dye available, on par with the color purple in the Roman Empire (Piponnier 16). In Mason’s translation, the cloth is not just silk but samite, the upper echelon of silk, often exquisitely woven with thin strips of precious metal (Piponnier 20). The baby girl is taken in by a porter’s daughter and named Frene. The porter’s daughter knows the girl must be of noble lineage to possess such a rich fabric. These clothes and fabrics add much more to Marie’s narratives than just realistic texture. Clothing and cloth often figures prominently as a plot device in the Lays. Frene, described above, is eventually reunited with her mother and twin sister when her mother sees the familiar strip of samite laid across a wedding bed: “Looking upon the bed she marked the silken coverlet, for she had never seen so rich a cloth, save only that in which she had wrapped her child” (Mason 99). In the Lay of Gugemar, two lovers on the night of their separation tie knots in each other’s clothing that only the other may undo. They discover and recognize each other later in life by those knotted clothes (Mason 21). Going beyond the scope of fabrics and textiles, Marie de France also carefully constructs costumes to develop her characters’ important traits. While wealth and nobility are important aspects of her female characters, Marie takes great pains to establish them as virtuous as well. In 12th century France and in its immediate past, ostentatious or “flashy” costume was frequently associated with prostitutes (Gibb 367) or even with licentiousness or pride (Smith 96). By contrast, Marie arrays her characters richly but simply. Underneath her sumptuous cloak, Lanval’s Lady wears a dress of spotless white linen (Mason 74). Laura Hodges hypothesizes that layering plays and important role in costume symbolism in French romance (although she applies it specifically to the Canterbury Tales). She cites a sermon by Augustine of Hippo which describes the inner and outer clothing of the ideal wife. To quote Hodges directly, “In Augustine’s analogy, the linen cloth used for undergarments that are worn but not observable represents a person’s spiritual intent. In contrast, the … cloth worn in outer garments that anyone may see represents bodily actions” (Hodges 4-5). As mentioned earlier, Marie’s lifetime marked the first time in women’s fashion where garments were made to closely fit the body. Within Marie’s lifetime, the tight dress became a symbol of aristocratic beauty (Smith 96), in contrast with earlier sermons that denounced tight dress as sexually immoral. In keeping with the fashion of the time, Marie takes the previously libidinous tight dress and makes it a symbol of fidelity. This would have been immensely appealing to her noble readers. Lanval’s Lady comes to mind, again, in particular. “The lady was dressed in a white tunic and shift, laced left and right to reveal her sides” (Burgess 1774). Not only does the color white call to mind purity and light, but Lanval’s Lady may be considered a paragon of amorous fidelity. The Lady is ideal in virtually every way: astoundingly beautiful, extravagantly wealthy, and faultlessly virtuous. She places but one condition on her relationship with Sir Lanval: “I admonish, urge, and beg you not to reveal [our love] to anyone!” (Burgess 1770). Lanval soon enough lets slip the secret, however, and is sentenced to death unless the mysterious Lady he boasted of comes to claim him. Lanval waits for his death, knowing he has failed in the one thing the Lady asked of him. However, the Lady appears before the date of his execution in her gorgeous fitted dress and takes Lanval back despite his failure (Burgess 1774). Such a dress would have been considered scandalously revealing not too long before Marie’s lifetime, but by arranging it on a character so faithful to her lover, she makes it a symbol of her loyalty. Tight clothing also figures as an important symbol in the Lay of Gugemar. Gugemar and his lady, another fabulously rich beauty, tie knots in each other’s clothing on the eve of their long separation. The Lady ties a knot in his shirt and he ties a belt around her waist (possibly a chastity belt). The knots are such that only the one who tied it may undo it without cutting it. They pledge to each other that they will give their love to no one but the one who can untie the knots; “[I] make this covenant with you, that never will you put your love on dame or maiden, save only on her who shall first unfasten this knot,” the lady says, and Gugemar “[requires] of the dame that she would never grant her love, save to him only, who might free her from the strictness of this bond, without injury to band or clasp” (Mason 15-16). Both remain faithful to and rediscover each other by this promise. The emotional climax of many of the Lays involves some significant piece of fabric or clothing. Gugemar concludes with the reunion of the lovers, who have recognized each other by the knots in their clothing. Frene finds her family with the help of a strip of silk. Laustic also contains such a resolution, but while Gugemar and the Ash Tree end on triumphant notes, Laustic is a tragedy. Two illicit lovers talk long into the night through a window and the wife justifies her absence from bed by saying she is listening to a nightingale. Her jealous husband has the bird caught and kills it before her horrified eyes. The emotional climax comes when he hurls the little corpse at her, staining her tunic with blood (Burgess 1776). To attack or damage a woman’s clothing was a grievous violation of person dignity in medieval France; such matters were often brought before a court (Pipponier 104). For a husband to damage his wife’s clothing would be symbolically on par with marital rape, for what legal power did a wife have over her husband? In Laustic’s denouement, the woman’s lover entombs the nightingale in samite and gold. Burying so humble a creature in so precious a cloth adds to the emotional intensity of the story. When reading the Lays, it is almost impossible not to notice the abundance of clothing description, or the frequency with which some significant piece of fabric appears. It is equally impossible to come to an informed conclusion about the Lays without taking into consideration the paramount importance of these fabrics and fashions. Costume and cloth in the works of Marie de France are may be thought of as embroidery; it brings beauty and texture to the narrative, a shimmering thread that holds the tapestry together, to which the eye cannot help but be drawn. Works Cited Burgess, Glyn S., and Keith Busby, trans. "Lanval" and “Laustic.” 2002. Norton Anthology of World Literature. 2nd ed. Vol. B. W. W. Norton Inc, 1984. 1769-776. Print. Gibb, Andrew J. "Pilgrims and Prostitutes: Costume and Identity Construction in Twelfth-Century Liturgical Drama." Comparative Drama 42.3 (2008): 359-81. JSTOR. Web. Hodges, Laura F. Chaucer and Costume: the Secular Pilgrims in the General Prologue. Cambridge, England: D.S. Brewer, 2000. Print. Heller, Sarah-Grace. Fashion in Medieval France. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 2007. Print. Mason, Eugene, trans. Lays of Marie De France and Other French Legends. London: Aldine, 1964. Print. Piponnier, Francoise, and Perrine Mane. Dress in the Middle Ages. Trans. Caroline Beamish. Yale University, 1997. Print. Smith, Nicole D. "Estreitement Bende: Marie De France's Guigemar and the Erotics of Tight Dress." Medium Aevum 77 (2008). JSTOR. Web. Wright, Monica L. Weaving Narrative: Clothing in Twelfth-Century French Romance. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State UP, 2009. Print.