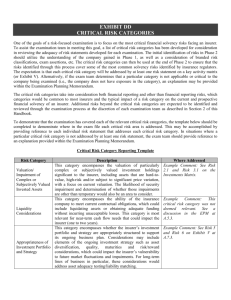

INSURANCE REGULATION IN A NUTSHELL

advertisement