Abstract - University of Leeds

advertisement

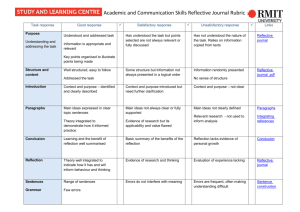

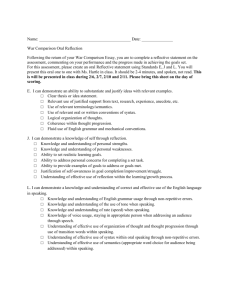

A reflexive critique of Learner Managed Learning Michael Doyle Education Development Unit University of Salford m.doyle@salford.ac.uk This is one of a set of papers and work in progress written by research postgraduates (MPhil and PhD) at Lancaster University's Department of Educational Research. The papers are primarily offered as examples of work that others at similar stages of their research careers can refer to and engage with. 1 Abstract ‘Learner autonomy’ and ‘learner-managed learning’ (LML) are topical educational goals and learning strategies for policy makers and practitioners, particularly in Adult Education and Life-long Learning. This paper uses a highly reflexive approach to address three issues central to these goals and strategies. Firstly, it analyses the theoretical premises of LML within emerging discourses of citizenship, progressive adult education theory and ‘autonomy’ in relation to theories of ‘risk’ and uncertainty. Secondly, it critically examines the pedagogical assumptions underpinning practices intended to develop LML: in particular, the use of learning contracts, experiential learning and reflective practice. This leads into the third issue: a critique of LML practice from an emancipatory/transformative perspective. The context of the study is a Foundation Degree prototype in which the purpose is to use LML to promote and develop learner autonomy. The paper concludes with an analysis of how LML needs to be interpreted within a less instrumental, more constructivist, relational and social theory of learning, which, through a process of reflective dialogue, engages the learner in a critically reflective construction of meaning. 2 INTRODUCTION The purpose of this paper is to offer a critical analysis of teaching and learning strategies used increasingly in higher education, which emphasise the use of learner-managed learning (LML). The objective is not to dismiss the approach – on the contrary, as the author is an advocate and keen practitioner of the process. However, the paper represents a reflexive attempt to examine conceptual and pedagogical underpinnings of this approach to adult learning. In this respect the process represents an exercise in critical research which Alvesson and Skoldberg (2000: 144) characterize as ‘triple hermeneutic’: interpretive social science with a critical interpretation of “unconscious processes, ideologies, power relations and other expressions of dominance that entail the privileging of certain interests over others”. The context of the study is a pilot Foundation Degree, which started in October 2001. It was launched (DfEE, 2000a) within a New Labour ‘Third Way’ discursive wrapper (Fairclough, 2001), which characteristically attempts to synthesise potentially conflicting elements. In the case of the Foundation Degree the contrast is between economic and democratic agendas, as represented by a ‘return’ on learning which enhances student employability in a global economy, while widening access to higher level learning. However, the dominance of the economic and utilitarian agendas, over the democratic, in education policy and practice over the past twenty years has been illustrated by Coffield (1999). Nevertheless, this discursive hegemony is contested, particularly within an androgogical and humanistic tradition of adult 3 learning, which stresses personal growth and transformation, learner autonomy and empowerment. Therefore the Foundation Degree case study provides an opportunity, in Freirean terms (1970), to critically evaluate the potential to develop liberatory, transformational learning within a dominant discursive framework that is geared towards the ‘domestication’ of its students in the interests of a narrow economically driven conceptualization of Lifelong Learning. This involves problematizing the ‘surface and deep structures’ (Deetz and Kersten, 1983, Frost, 1987) underlying teaching and learning strategies within LML; in other words, the taken for granted acceptance of existence as rational and comprehensible, as opposed to the questioning of beliefs and values upon which the surface structures rest. The three questions to be addressed therefore are as follows: what are the theoretical premises on which the LML module (called Independent Learning) and the curriculum model for the Foundation Degree are based? Secondly, what are the pedagogical assumptions on which the LML learning process is conceptualized and framed? The final issue concerns the efficacy of the module in supporting processes of LML in its emancipatory conceptualization. In addressing these issues the paper represents a critically self-reflexive exercise; a process of ‘double loop’ learning (Argyris and Schon, 1974). The paper is structured as follows: following contextual information on the Foundation Degree, the curriculum model of the actual case study is 4 summarized and the Independent Learning Module outlined. This is then positioned within a domesticating/emancipatory theoretical framework involving situating the curriculum firstly within the debate on the Learning Society (Schon, 1971, Ranson, 1998) and developments in Lifelong Learning; secondly in terms of conceptualizations of learner autonomy within a period described by Giddens (1990) as a ‘juggernaut of late modernity’, characterized by ‘risk’ (Beck, 1992), and including the ‘discursive elision’ of LML with ‘managerialism’ (Harrison 2000); and finally the conceptual roots of the curriculum are located within the progressive premises of adult education. The aims, learning outcomes and teaching, learning and assessment strategies of the module, and more broadly the programme and curriculum model, are then evaluated within this conceptual context. There is particular emphasis on the analysis of the use of learning contracts (called learning agreements), experiential learning and reflection in the planning and development of student learning. These represent the assumptions being investigated on which the LML process is conceptualized and framed. The third issue of transformation through LML in an emancipatory sense is then evaluated The paper concludes with an analysis of how the module and the broader curriculum might be interpreted within a more constructivist, social and situated theory of learning, which through a process of reflective dialogue could offer a less rationalistic, less individualistic, and more hermeneutic 5 approach, engaging the learner in a critically reflective construction of meaning. Foundation Degree – The Context The case study is one of twenty one selected by the Higher Education Funding Council (HEFCE), through a bidding process for development funding and additional student numbers. The Secretary of State for Education and Employment undertook a consultation exercise (DfEE, 2000b) on proposals for the introduction of a new qualification, the Foundation Degree. This was to be a sub-degree qualification, which, in the course of time, was expected to become the dominant qualification at this level. As a consequence it is anticipated that institutions will re-develop existing subdegree programmes (such as HND’s) to conform with the requirements for Foundation Degrees. It is also the Government’s intention that the bulk of any growth in higher education will be achieved through Foundation Degrees. Given the Government’s target of 50% of the population experiencing higher education by the age of thirty by 2010, this indicates its priorities for higher education and reinforces the link between higher education, economic agendas and technical-rationalist, human resource conceptualizations and discourses of Lifelong Learning. The rationale for such priorities lies, in the context of a global economy, in the shortage of and increased demand for people with intermediate-level skills, across all sectors of the economy, who can operate effectively in posts 6 generically referred to as ‘higher technicians’ and ‘associate professionals’; in ‘deficiency’ conceptualizations of higher education and its graduates (Coffield, 1999); and in a perceived need to rationalize the range of qualifications below honours degree level. Foundation Degrees are expected to meet these needs by equipping students with the combination of academic knowledge and technical and transferable skills demanded by employers, while facilitating lifelong learning for the workforce and enhancing the ‘diversity and differentiation’ (Neave, 2000) of higher education, thus combating social exclusion. The award will attract a minimum of 240 credits (120 each at levels 1 and 2), and will be awarded by individual universities. The CVCP (2000) summarized the essential features as: employer involvement; development of skills and knowledge; application of skills in the workplace; credit accumulation and transfer and progression within work and or to an honours degree. Foundation Degree in Community Governance and the Independent Learning Module The case study is a collaborative development between a consortium of one university, five of its associate colleges and the local authority employers within which the colleges are located. The University will award the Foundation Degree, with curriculum delivery largely in the local colleges. The target students are local authority staff and a small minority of people working with the local authorities in the delivery of policy and strategy, for example the 7 voluntary sector. The incentive for the employers is the policy and the funding thrust to ‘modernisation’ (Newman, 2000): With all the initiatives for local government either here or coming soon, “no change” is not an option. The challenge for local government is to change culturally, to seek new ways of working, and to reach beyond its organizational boundaries (Improvements Development Agency, 2001) Such change will require a major programme of learning and skills development for local authority staff. Coupled with this, the trend in local government is to employ fewer, more highly skilled staff who can work outside traditional departmental hierarchic structures and who can think and operate in a strategic way. For many Local Authorities, ‘upskilling’ the existing workforce represents a more viable alternative to employing new staff. The employer members of the consortium have highlighted that there are underdeveloped opportunities for accredited study in vocationally-related areas of modern local government. This is especially true for ‘nonprofessional’ administrative staff at and below the level of Principal Officer Grade 5. That represents the majority of Local Authority staff, which is also mainly non-graduate and not usually eligible for substantive secondment, for example to traditional first degree programmes. Existing public administration courses, for example the DMS have yet to acknowledge the new ‘facilitative’ and ‘capacity-building’ roles increasingly required of Local Authority staff. 8 The predominant view of the employers is that the time is appropriate for the introduction of a new qualification, which offers a fresh approach to the issues relating to Local Government. The strategy for regionalisation and more community involvement in governance has put pressure on Local Authorities to change their existing culture and way of working. It is their view that the role of the Foundation Degree would be to support the internal staff development required to facilitate the changes needed within Local Authorities. The programme learning outcomes therefore have a clear emphasis on the ‘return’ to the organization in terms of its investment in human capital. Of the five stated outcomes only one is couched in terms of the individual, rather than the ‘organisation’, and this stresses the identification of ‘ongoing professional development needs and strategies’. The programme has a workrelated emphasis, with learner-managed learning as its focus. The curriculum model (Figure 1) reflects the work-based focus of the learning: the Independent Learning (level 1) and Work-based Project (level 2) modules (categorised as ‘Applications Modules’, reflecting the work-related, LML context) are positioned centrally as the focus developing from the APL/APEL and Learning Contract entry stage. The other level 1 modules are classified as ‘Strategic’, giving a foundation propositional knowledge base, and the level 2 modules more open-ended, and classified as ‘Issues’, permitting a degree of student choice reflecting professional interests. 9 The Independent Learning Module is the first taken in the whole programme. Its key purpose is to introduce students to the rationale and practices of LML. It is intended that after semester 1 the reflective practice and self managed learning introduced by the module will be further developed and monitored throughout the programme through the Personal Advisor and the use of Personal Development Planning. The Independent Learning module learning outcomes reflect the priority given by Dearing (1997) to LML, which he identified as the most significant ‘Key Skill’. In the module students negotiate the outcomes and assessment criteria for their learning within broadly worded parameters, although within a work-based context. This involves producing a ‘learning agreement’ (a form of learning contract) within the first four weeks of the module and the subsequent use of guided reflection throughout the semester. Processes of reflection are built into the module assessment. The module itself provided the model for the whole curriculum, and the processes of its delivery. In contrast to the organizational emphasis of the programme learning outcomes, the Independent Learning module aims to: ‘support students in their development as self-directed learners in individual and group professional contexts’; ‘develop capabilities as reflective practitioners’; and ‘develop skills of critical evaluation in their personal and professional development.’ Specific learning outcomes therefore refer to ‘personal’ as well as professional development through learning. The curriculum model and the Independent Learning module are rooted in experiential models of learning 10 (Kolb, 1984), with the aim being the development of autonomous, selfmanaged learners. Effectively, the espoused aims of the programme are organizational and managerial, while the curriculum model and learner strategy are embedded in progressive, androgogical conceptualizations of learning. The question is whether the assumptions on which this decoding and recoding of the programme in progressive terms are likely to deliver the aim intended: learner autonomy. Indeed as well as questioning the conceptualization of the ‘individual’ as learner with autonomy, it has to be asked whether this curriculum model and the Independent Learning module represent a classic case of what Edwards and Usher (1994), using Foucauldian conceptualizations of Power/Knowledge, argue is a situation where learners (and in this case workers) are being trained to exercise selfmonitoring and control within specific given parameters. If this is the case it represents what Harrison (2000) calls a ‘discursive elision’ – progressive discourse selectively and narrowly interpreted, used to veil managerial strategy. For the higher education teacher a key issue therefore is whether they are performing a domesticating or liberatory (emancipatory) function. For some the issue may not be problematic, although this brings into question the purpose of higher education. For Harvey and Knight if higher education is to play an effective role: 11 …then it must focus its attention on the transformative process of learning…critical reflective learners able to cope with a rapidly changing world. (Harvey and Knight, 1966:viii) The following section provides a conceptual matrix with which to subsequently analyse the module and the curriculum model. It begins to map out the theoretical premises on which the module and curriculum model is based; essentially the first question to be addressed by this paper. 12 Figure 1 Curriculum Model – Foundation Degree in Community Governance Modules Application Strategic Work-based Learning Issues Creating a Flexible Workforce Programme of Workshops to extend beyond the programme of study for Foundation Degrees Raising Standards Performance Management Quality Protects Initiative Community Communication Crime and Disorder Asset Building Dealing with Disadvantaged Society Accountability Support from Personal Adviser Up-date of Personal Development Plan leading to final Student Transcript Independent Learning Learning Contract and establishment of Personal Development Plan APL/APEL Process for those students over the age of 21 and with existing work experience. All students interviewed. 13 Learner autonomy and the Learning Society Three conceptual strands to learner autonomy are outlined in this section: the re-emergence of the concept of the individual within a discourse of ‘citizenship’; the post-modern conceptualizations of the individual dealing with uncertainty; and traditional conceptualizations of the adult learner within progressive perspectives. Emphases on learner autonomy have traditionally been underpinned by humanist democratic perspectives (Rogers (1978), Maslow (1968), Knowles (1984), Illich (1971)) rooted in ‘empowerment’, ‘selfrealisation’ and similar normative visions which have served to shape pedagogy. The western social and ideological contexts have influenced this positively with the focus on individualism, and the power of agency reinforced by the counterweight growth of uncertainty and risk brought about by poststructural and post-modern change. The ‘learning society’ and the need for ‘learning systems’ (Schon, 1971) are concepts used to make sense of a period of change. Ranson (1998) in tracing the lineages of the learning society claims we have reached a stage of citizenship within a learning society whose creative agency will be the key to economic and social innovation. Reflexivity and lifelong learning are seen as remedies to uncertainty, and Evans (1985) claims: Reflecting on the conditions for…lifelong education has led adult educators to develop a framework for a learning society as a society of learners, using their learning to inform their shaping of the society in which they live and work. It leads to pedagogy which advocates that according the learner the 14 responsibility to participate in shaping the purpose and process of learning is the most effective route to motivation and personal development. Ranson claims that the purposes and conditions for the learning society lie in democratic politics, claiming reasoning in public discourse is the vehicle to a learning democracy (1998). Ranson traces the roots of democratic learning to Lindeman and Dewey. For Dewey (1958), knowledge only has meaning through action, and Ranson sees action through citizenship as a means of learning, or ‘becoming’; the route to ‘unfolding agency’ (Ranson 1998:19). The discourse of learning as self-development has become central to public policy in the UK. ‘The Learning Age’ (DfEE, 1998) stresses self-actualisation through action, with emphases on individuals, workplaces and providers of learning opportunities becoming more flexible. New and alternative sites of learning are being identified (for example, work-based) as well as a growing interest in the significance of informal learning, given impetus by the outcomes of the ESRC’s programme, The Learning Society (Coffield, 2000). The increasing stress on reflexivity signifies the increase in options and choices and the necessity of decision-making in an increasing period of uncertainty. Edwards (1998) observes that previously structured choices and opportunities are no longer held to be as determining of biographies as before. 15 The logic of modernity is contested, asserts Beck (1992), replaced by a new modernity of ‘reflexive modernisation’. This, argues Edwards (1998): requires social formations, organizations and individuals to change, learn to change and change to learn. Beck (op. cit.,) conceptualized this in the ‘risk society’, with de-standardised structures resulting in greater individualisation (though not necessarily an increase in agency). However, for Beck the contemporary world opens up possibilities for individuals (not all – reflexivity and lifestyle choices are not equally distributed; a significant issue in view of democratic perspectives above) to reflect critically on these changes and the social conditions of their existence, and, for Lash and Urry (1994:32) the chance to potentially change them. For Giddens (1990, 1991) modernity represents a process of constantly breaking with tradition through a reflexive monitoring to develop ‘the new’: who we are becomes something we experience as a question to be answered continually. For Lash and Urry the result is that: …reflexivity transfers from monitoring the social to monitoring the self (1994:41) In late modernity for Giddens reflexivity is radicalized by the plethora of information requiring life-planning, lifestyle choices, and in the construction of 16 self-identity. Decision making and ambiguity also result in ‘existential anxiety’. However, Giddens’ notion of the reflexive monitoring of the self also implies that lifelong learning can involve personal development opportunities. Both Beck and Giddens share the view that reflexivity of the self and the social is a rational process, concerned with reasoned decision-making; while Edwards (1998) contends that an initiation into the practices of reflection and pedagogies of reflection are integral to reflexive modernization, a flexible workforce of lifelong learners and a de-standardized workplace. Hence the dangers highlighted by Harrison (2000) of the enmeshing of human capital managerial discourse and learner autonomy, conceptualizations rooted in more progressive and humanist forms. This is reinforced by Usher and Solomon in their comment: …with the replacement of what constitutes legitimate knowledge (as constituted by disciplines and therefore outside the organization) to that constituted by performance agreements (and therefore within its control), the organization can also ensure that the ‘right’ performative things are learnt. (1998:6) Consequences of framing domesticating educational (or training) practice within liberatory discourse has been a key issue in, for example the debate on key/core skills, by Hyland (1998), ‘performance’ by Holmes (2000), the ‘competence’ debate (Tarrant (2000), Norris (1991)), and the ‘Capability’ movement (Stephenson, 1993) 17 In contrast to this the progressive tradition of adult learning has established an academic orthodoxy committed to the verification of a general theory of adult learning which, according to Brookfield (1992): Judged by epistemological, communicative and critically analytic criteria, theory development in adult learning is weak and is hindered by the persistence of myths that are etched deeply into adult educators’ minds. Such ‘myths’, claims Brookfield (1995), promote adult learning as inherently joyful, that adults are innately self-directed learners, that good educational practice always meets the needs articulated by the learners themselves, and that there is a uniquely adult learning process and form of practice. Brookfield (1995) provides a categorization of four overlapping strands of adult learning, which he claims constitute ‘an espoused theory of adult learning that informs how a great many adult educators practice their craft’. The categories are selfdirected learning, critical reflection (the basis for Mezirow’s (1990,1991) theory of transformative learning), experiential learning (usually associated with Kolb (1984)), and more recently ‘learning to learn’ (for example, King and Kitchener’s (1994) concepts of epistemic cognition and reflective judgement). The Independent Learning module, and therefore the conceptual underpinning of the curriculum model of the whole Foundation Degree has strands of all four ‘myths’. It’s rationale can also be located in the motivation to equip ‘citizens ‘ with the capabilities to contribute to and self-develop within the ‘learning society’, and be equipped with the reflexive capabilities to 18 monitor the self in a time of uncertainty and ‘complexity’ (Fullan, 1999). This is indeed an ambitious model of curriculum design. The Independent Learning Module and the Foundation Degree Curriculum Model The module and the curriculum model for the programme are rooted in several conceptual strands, which are translated into pedagogical practice. The self-managed learning humanist tradition of experiential learning is linked into a rationalist process based on the use of learning contracts. Within the process of action planning and review of progress on the contracted learning is harnessed the development of the learner as a reflective practitioner. These three strands (the assumptions referred to in the second research question in the introduction), on which the LML learning process is conceptualized and framed, will be analysed in this section. Learning contracts The learning contract is used at a programme level to clarify the commitments on the student and the colleges, and is used to monitor progress in keeping with the Personal Development Plan (Figure 1), and ultimately the student transcript. The Independent Learning module also uses a learning contract (called learning agreement) in a more specific way, effectively as an action 19 plan. In negotiating the learning agreement for the module students are expected to produce an action plan indicating how the agreed learning is to be managed. The learning agreement is then used as a monitoring tool for the student to be presented at tutorials. In principle, the process is adapted around the Kolb Learning Cycle (1984). Superficially the process seems rooted in a rationality and a discourse which is instrumental rather than communicative in Habermassian terms; domesticating rather than emancipatory in Freirean conceptualizations. The concept of the learning contract is based on androgogical (Knowles, 1986) assumptions regarding the nature of learning and adult learners. For Knowles the learning contract is a means of empowering the learner in the process of learning, and is seen, in Habermassian terms, as a means of achieving the ‘ideal speech situation’ of mutual respect, although Gosling (2000) doubts whether this is possible in formal learning contexts. In contrast Edwards and Usher (1994) argue that such ‘empowering’ is a form of discursive control in Foucault’s ‘Power/Knowledge’ conceptualization. Ideally the negotiated learning contract allows the learner the opportunity to work in an area relevant to personal needs and interests. In this sense, learning contracts ought to provide a means of facilitating deep learning (Marton et. al. 1984), given an assumed high level of student motivation and affective involvement (Boud, Keogh and Walker, 1985). However, Caffarella and Caffarella (1986) question the claims made by, for example Knowles (1980), amongst others, that using learning contracts fosters general competencies in independent learning 20 For Anderson, Boud and Sampson, learning contracts provide learning experiences which are ‘relevant’, ‘autonomous’ and ‘structured’. They also involve a degree of technical rationality, as their comment suggests: By documenting plans, outcomes and assessment criteria in advance all interested parties…can have similar expectations of the learning project. (1996:11) This takes no account of the learner’s needs to develop skills in this area (Brookfield, 1985), or that learners may not know what they need to know, and that learning is viewed in a simple ‘input-outcome’ perspective. This was recognized by Tough (1979) who observed that learning goals change as a learning project progresses, regardless of the clarity of initial objectives. In the author’s experience this is the case with LML linked into learning contracts. Students rarely reproduce the outcomes identified in the learning agreement as the end product. Students often re-negotiate the agreement. Experience and processes of reflection are instrumental in these changes. An issue beyond this paper is how this re-negotiation is perceived by students working within a dominant learning paradigm rooted in rationality: is it, for example, de-motivating, resulting from failure to meet initial targets, or energizing? Of course the reflective process structured around the tutorials may help to address this issue. 21 Experiential learning Given Tough’s observation (op. cit.,) it would appear that learning contracts in conjunction with experiential learning are contradictory. However, there is uncertainty about the nature of experiential learning. For Eraut (1994) experience is initially apprehended at the level of impressions, requiring a further period of reflective thinking (the issue of time in his critique of Schon’s (1983) ‘reflection in action’) before it is either assimilated into the existing cognitive structure, or induces change in that structure to accommodate it. Moon (2000) contends experiential learning can result from experience in its broadest conceptualization, claiming, however, that it is construed, subsequently, thorough reflection, in cognitive terms. With Kolb (1984), for example, Moon’s interpretation is that the process of learning perpetuates itself: the actor becomes observer, with the quality of reflection being crucial to the quality of learning. The Independent Learning module uses this concept of experience through the tutorial process, which is effectively a formalized forum for the application of the Kolb cycle of reflective observation on concrete experience, abstract conceptualization and subsequent action planning based on the reflective learning (Kolb’s ‘active experimentation’). Students are entitled to up to five tutorials over the cycle of the module. Learning agreements are therefore used with the expectation (by the tutor, not necessarily by the student) that they will be changed. The module therefore has a rationalist framework but practice is in many respects constructivist. 22 The Kolb learning cycle has had a significant impact on pegagogical thinking and practice in LML. However, Miettinen (2000) is extremely critical of Kolb. He claims that the four stages in the cycle are artificially separated; that they don’t connect in any organic or necessary way. He also accuses him of selectively citing Dewey and using a marginal piece of research to construct a misinterpretation of him to his own advantage. For Dewey observation and reflection are highly contextualised. Miettenen asserts that for Kolb and the adult learning tradition experiential learning represents a kind of …psychological reductionism that Dewey considered a misrepresentation of his anti-dualist conception of experience (Miettenen, 2000) The result for Miettenen is a perpetuation of something similar to Brookfield’s ‘myths’ of adult learning – rational thought and reflection linked into a belief in every individual’s capacity to grow and learn, the progressive underpinning of lifelong-learning. He claims the result is that: …the belief in an individual’s capacities and his individual experience leads us away from the analysis of cultural and social conditions of learning that are essential to any serious enterprise of fostering change and learning in real life. (Miettinen, 2000). 23 If experiential learning is essentially based on a methodological individualism, then where, in the context of the Independent Learning module and the curriculum model, does that leave the reflective practitioner? Reflective practice The module and the curriculum model make significant assumptions about the learner. Both are premised on the methodological individualism referred to above, which assumes a significant power of agency resting with the individual. Yet the learner will be returning to education with former educational experience likely to be built around a didactic paradigm, which is likely to shape expectations of future experience on the programme and the individual’s role in that process. Students will experience only a short induction (two days, of which half a day is given to Independent Learning) before the module begins, contrary to the module specification which refers to an ‘extended induction’. Boud and Walker (1998) criticise the incorporation of reflection, when it is only partly understood, into teaching contexts which are not conducive to the questioning of experience. They cite situations which do not allow learners to explore Dewey’s (1933) ‘ state of perplexity, hesitation and doubt’; Brookfield’s (1987) ‘inner discomforts’ and Mezirow’s (1990) ‘disorientating dilemmas’. They complain that many teachers equate reflection with thinking. They assert this has resulted in the translation of reflective practice into 24 …such simplified and technicist prescriptions that their provocative features…become domesticated in ways which enable teachers to avoid focusing on their own practice and learning needs of students This raises a number of questions for the module and programme. Is reflection a tool to facilitate, or a process of, learning? Is it to be, in Dewey’s conceptualization, a means to learning in context, or an emancipatory ‘knowledge constitutive interest’ in Habermassian critical reflection terms? How are learners taught to reflect? Do they need to transfer and develop through levels of learning before they have the critical tools (Perry, 1970; King and Kitchener, 1994; Belenky et al 1986; Bateson, 1973 ; Van Maanen 1977, 1991; Mezirow, 1990; Saljo,1982; Marton et al.,1993; Moon, 2000), experience (Kolb, 1984) or maturity (Moon, 2000) to reflect ? Do they need to reflect in action (Schon 1983) or on action (Eraut, 1994)? Students reflect on action through the tutorial process. How is the learning to be represented and therefore assessed? Forty percent of the assessment for the module is given to the reflective commentary, a summative rather than formative piece of work. This commentary is therefore a representation of understanding of the processes of learning. Eisner (1991) in this respect claimed that individuals develop meaning in the process of learning and explore and develop it further in the process of its representation. Can the students develop reflective practitioner capabilities at this early stage of their learning and development, or should the assessment of these learning practices be incorporated into strategies later in the programme? Although the 25 programme has a work-based emphasis in the learning, the methods of assessment and the representation of learning are structured within an academic framework and discourse, which the students at this stage of their development may not be aware of. Yet Usher (1985) observed that students he worked with had difficulty using personal experience in deepening their knowledge: he claims they had learned not to value their experience in comparison to what they perceived to be academic or scientific knowledge. Learning was therefore superficial as it was not being linked with existing cognitive structures. The module specification states: ‘Emphasis is placed on student learning and the process of reflection. Students will be briefed, through an extensive induction, on the framework for learning, including the definition of aims and objectives, roles, responsibilities and expectations in the learning and assessment process.’ In being ‘briefed’ in a formal way about reflection, that is given the propositional knowledge, the assumption in the pedagogic practice is that the learners will translate this propositional knowledge into processes and practice: ‘espoused’ knowledge is expected to become ‘theory in use’ (Argyris and Schon, 1974). Yet Eraut, based on Ryle (1949), comments Knowing how cannot be reduced to knowing that (1994:107) 26 In supporting the development of capabilities of reflective practice, there lies a significant responsibility on, and an investment of trust in the tutorial process for the module, and in the Personal Advisor (Figure 1) for the programme. The issues and questions raised in this section of the paper relating to reflective practice and the concept of the reflective practitioner are relevant to discussion of this module and the curriculum programme as a whole. However, detailed investigation of the issues raised is beyond the scope of this paper. LML, critical reflection and emancipation The third issue to be addressed concerns the efficacy of the Independent Learning module and the curriculum model in supporting processes of LML in its emancipatory conceptualization. Such conceptualizations are rooted in Habermas’ emancipatory knowledge constitutive interest (1971): knowledge is developed through critically reflexive modes of thought and enquiry to understand the self in human context with the purpose of transformation. Mezirow (1990, 1991) has built a theory of transformative learning on Habermas’ conceptualization of communicative learning, involving the revision of ‘meaning structures’ through what he terms a process of ‘perspective transformation’. His theory is built on the centrality of experience, critical reflection and rational discourse. In reviewing the plethora of literature on Mezirow, Taylor (2001) criticizes him for perceiving transformation in individual, socially de-contextualised terms 27 involving transformation of the self with subsequent uncritical social reintegration. This is supported by Tennant (1993) who claims Mezirow overstates agency and under-theorises the influence of the social dimension. Hart (1990) criticises Mezirow for not recognizing the issue of power differences that need to be addressed for critical reflection to occur in a ‘communicative’ rather than an ‘instrumental’ way. Mezirow is criticized by Clarke and Wilson (1991) for his rationality, which is rooted in humanistic assumptions, and is ‘a-historical and decontextualised’. Although Mezirow subsequently attempted to address these criticisms (1991), claiming that they misinterpreted an emphasis on self-direction and the autonomy of the individual as a disregard for collaborative social action, and that by 1996 he acknowledged that learning is situated in a social context, Taylor (2001) notes that he failed to maintain the connection between the construction of knowledge and the context within which it is interpreted. The issue of social context and agency links Mezirow to the earlier discussion on adult learning theory (Miettinen, 2000, Brookfield, 1995). According to Taylor (op. cit.,), Mezirow suggests transformative learning is a process that all cultures should aspire to, but in equating helping adult learners to learn with acquiring more developmentally advanced meaning perspectives as the goal of adult education, Taylor argues, that as in a constructivist perspective theories are context specific (citing Gallacher, 1997:114), then transformative learning ‘is a derivative of the creator’s own culture’ (Taylor, 2001:30). 28 There are questions therefore about whether LML should be conceptualized in transformatory/emancipatory terms. From a cultural and contextual perspective this has to be seen in the ways a higher education experience in the UK is framed, and according to Brockbank and McGill (1998), recent aspirations for learning in universities cannot be separated from the debate about the purpose of universities. For Harvey and Knight (1996) this means learning as a transformative process. For Barnett (1997), it is about moving on from critical thinking to ‘critical being’, engaging students more holistically and incorporating critical self-reflection and critical action. The issues are essentially normative. Reflexivity seems central to these processes, particularly in a postmodern, post-structural paradigm. Should or can LML be emancipatory? In rationalist and universal adult learning theory terms it can aspire to be. From a constructivist perspective the learner will construct meanings of significance in context. Perspective transformation, the transition of meaning systems, or developments in cognitive structures do and will happen. However, this is likely to happen in relational ways specific to particular contexts, rather than as a result of unfettered agency. LML, reflexivity, rationality and ‘judgement’ Having set the Independent Learning module and the curriculum model, and an evaluation of the assumptions on which it is based in a theoretical context of interpretations of learner autonomy (democratic citizens within the learning 29 society (Ranson, 1998, Schon, 1971); complexity, uncertainty and risk (Giddens, 1990, 1991, Beck 1992) and adult learning theory), the final section of this paper will attempt to construct an interpretation of the Independent Learning module and the curriculum model in a way that reflects an attempt by a practitioner to come to terms with the issues raised so far. Within the debates on the purpose of higher education critical thinking, critical being and transformation feature strongly in the prevailing discourse. The debates on knowledge and performativity have cast doubt and uncertainty on the nature and purposes of learning (Barnett, 1990, 1997). Brockbank and McGill (1998) claim that the key to immunity from such influences lies in using a rationality defined on the basis of personal reason and adopting a pedagogic practice that enables students to challenge existing paradigms. Under this conceptual umbrella they group ‘criticism’ (Barnett, 1990), ‘critical reflection’ (Mezirow, 1990), ‘reflexivity’ (Beck et. al., 1994) and ‘critical thinking’ (Brookfield, 1987). A problem with rational perspectives is the traditional Cartesian dilemma between thought and action, the plan and the outcome, the learning agreement, its revisions and the actual pieces of work submitted for assessment. The module and the curriculum model therefore need to be placed in a frame where changes to initial thinking and planning are the norm, and indeed, through the use of critical reflexivity within a community of shared experience, become reality. 30 The Independent Learning module and the curriculum model are actually well placed for these adaptations. The emphasis on work-based learning in the module and the programme addresses the constructivist issue of learning in context (Ramsden (1988), has recognized the significance of context in the development of student approaches to learning); Clarke and Wilson’s (1991) critique of Mezirow. Critiques of the focus on the individual learner within studies on self-directed learning are well established. Brookfield (1984) complained that: …the social setting for a great deal of self-directed learning has been ignored…the importance of learning networks and informal learning exchanges has been forgotten. In 1980 Brookfield drew attention to the importance of informal learning networks to self-directed learners, and a great deal of work is currently being done on informal learning in multiple sites of learning (Coffield, 2000, Eraut, 2000, Schuller et. al., 2001). This emphasis on networks (of course not a new idea – Schon, 1971) within contexts reflects the significance of the social and situated nature of learning (Lave and Wenger, 1991). The Independent Learning module, in the outline of learning and teaching strategies, makes reference to ‘informal peer support groups (action learning sets), on-line discussion groups and e-mail tutor/group contacts as well as formative whole group/tutor progress tutorials’. There is already potential in this, along with the guidance offered by the Personal Advisor (Figure 1), to reshape the emphasis from a rationalistic to a more negotiated, developmental and constructivist 31 approach. This means the process should become less instrumental and goal related, and more developmental. The methodological individualism of experiential learning and the concept of the individual reflective practitioner ought to be replaced by a more social, relational and hermeneutic process in the action learning sets. Brockbank and McGill (1998) encapsulate this in the term ‘reflective dialogue’, a shared and social method of developing critical perspectives and self-reflexivity. There is more in this approach linked to Dewey rather than Habermas. Does this mean that the approach is domesticating rather than emancipatory, in Freirean terms? This is not necessarily the case. The approach is similar to Kemmis’ (1985) view that: …reflection is action oriented, social and political. Its produce is praxis (informed committed action), the most eloquent and socially significant form of human action Hager (2000) contends that such a Deweyan approach, based on developing knowledge as judgement through reasoning and acting through praxis in context combines the dualism of Cartesianism. The module and the curriculum model therefore could continue with the learning agreement and critical reflective dialogue within a constructivist, hermeneutic, inter-subjective, rather than individual, rationalist Kolb-like framework. However, the issue of power differentials in roles and relationships 32 impacts on the degree of inter-subjectivity and reflective dialogue possible (Gosling, 2000), and therefore these issues would need to be identified and addressed in the reflective process. The assessment would need to be amended to reflect this, with greater emphasis on the process of reflection and learning rather than the product. The programme rationale acknowledges a workplace existence similar to that portrayed by Beck (1992): In particular, this requires an ability to manage uncertainty, take risks, cross boundaries and develop different decision-making approaches in conjunction with elected members. As a consequence of the abolition of traditional decision-making procedures, administrators are likely to be communicating more directly with members and the community. They are likely to be more accountable for triggering higher-order decisions and will be expected to manage knowledge in a much more sophisticated way. Such a world is not based on technical rationality; rather Fullan’s (1999) conceptualization of ‘complexity’. Reflexivity in dialogical, therefore shared reflective practice offers a possible route to dealing with such complexity in a way that recognizes the structural limitations on agency. This paper represents an exercise in critical reflection, in ‘double loop’ learning (Argyris and Schon, 1974), and a ‘triple hermeneutic’ (Alvesson and Skoldberg, 2000). The ‘deep and surface structures’ (Deetz and Kirsten, 33 1983) underlying LML have been problemetised, hopefully to the benefits of the students who will experience the programme. The praxis will continue to be subject to critical reflexivity. However, the process engaged in so far is self-reflexive, and requires to be presented for debate with colleagues in a process of reflective dialogue. 34 REFERENCES Alvasson, M., & Skoldberg, K. (2000) Reflexive Methodology. New vistas for qualitative research. London:Sage Anderson, G., Boud, D. & Sampson, J (1996) Learning Contracts. A Practical Guide. London: Kogan Page Argyris, C. & Schon, D (1974) Theory into Practice. San Francisco: JosseyBass Bagnall, R.G., (2000) Lifelong Learning and the Limitations of Economic Determinism International Journal of Lifelong Education 19:1, 20-35 Barnett, R. (1990) The Idea of Higher Education. Buckingham:OUP Barnett, R. (1997) Higher Education: A Critical Business. Buckingham: OUP Bateson, G. (1973) Steps Towards an Ecology of Mind. London: Paladin Beck, V. (1992) Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity. London: Sage Beck, V., Giddens, A. & Lasch, E. (1994) Reflexive Modernisation. Cambridge: Polity Press Belenky, M, Clinchy, B, Goldberg, R & Tarule, J. (1986) Womens’ Ways of Knowing. New York: Basic Books. Boud, D. Keogh, R, & Walker, D (eds) (1985) Reflection: Turning Experience into Learning. London: Kogan Page Boud, D. & Walker, D. (1998) Promoting Reflection in Professional Courses: the challenge of context. Studies in Higher Education, 23, 2, 191-206 Brockbank, A., & McGill, I. (1998) Facilitating Reflective Learning in Higher Education. Buckingham: OUP Brookfield, S. D. (1995) Adult Learning: An Overview in A. Tuinjman (ed.) International Encyclopedia of Education. Oxford: Pergamon Press Brookfield, S. D. (1992) Developing criteria for formal theory building in adult education. Adult Education Quarterly, 42, 2, 79-93 Brookfield, S.D. (1984) Self-directed adult learning: a critical paradigm. Adult Education Quarterly, 35, 2, 59-71 Brookfield, S. D. (1980) Independent Adult Learning Unpublished doctoral dissertation. University of Leicester. 35 Brookfield, S. D. (1985) Self-directed Learning: from theory to practice. San Francisco: Jossey Bass Brookfield, S.D. (1987) Developing Critical Thinkers: challenging adults to explore alternative ways of thinking and acting. San Francisco: Jossey Bass Caffarella, R.S., & Caffarella, E.P. (1986) Self-directedness and learning contracts in adult education. Adult Education Quarterly, 36, 4, 226-234 Clark, M.C., & Wilson A. (1991) Context and Rationality in Mezirow’s Theory of Transformational Learning. Adult Education Quarterly, 41, 2, 75-91 Coffield, F. (1999), Breaking the Consensus: Lifelong Learning as Social Control, British Educational Research Journal, 25:4 pp.479-499 Coffield, F. ed. (2000) The necessity of informal learning. Bristol: Policy Press CVCP (2000) Information for Members. I/00/173 Deetz, S. & Kersten, S. (1983) Critical models of interpretive research. In L. Putnam & M. Pacanowsky (eds), Communication and Organisations. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. Dewey, J. (1933) How We Think: a restatement of the relation of reflective thinking to the educative process. Lexington, MA, D.C. Heath Dewey, J (1958) Experience and Nature. Dover DfEE (1998) The Learning Age: a renaissance for a new Britain. London: HMSO DfEE (2000a), David Blunkett’s Speech on Higher Education, 15 February 2000 at Maritime Greenwhich University. London: DfEE DfEE (2000b), Foundation Degrees, A Consultation Document London:DfEE Edwards, R. (1998) Flexibility, reflexivity and reflection in the contemporary workplace. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 17, 6, 377-388 Edwards, R. and Usher R. (1994) Disciplining the Subject: the Power of Competence, Studies in the Education of Adults, 26:1 pp. 1-14 Eisner, E (1991) Forms of understanding and the future of education, Educational Researcher, 22, 5-11 Eraut, M. (1994) Developing Professional Knowledge and Competence. London: Falmer Press 36 Eraut. M (2000) Non-formal learning, implicit learning and tacit knowledge in professional work, in F. Coffield (ed.) (2000). Evans, N. (1985) Post Education Society: Recognising Adults as Learners. London: Croom Helm Fairclough, N. (2001), New Labour, New Language, London: Routledge Freire, P. (1970) Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Seabury Press Frost, P.J. (1987) Power, politics and influence. In F. Jablin (ed.), Handbook of Organisational Communication. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Fullan, M (1999) Change Forces: The Sequel. London: Falmer Gadamer, H. (1974) Truth and Method. New York: Seabury Press Gallagher, C. J (1997) Drama-in-Education: Adult Teaching and Learning for Change in Understanding and Practice. Ph. D Dissertation, University of Wisconsin. Giddens, A (1990) The Consequences of Modernity. Cambridge: Polity Press Giddens, A (1991) Modernity and Self-identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age. Cambridge: Polity Press Gosling, D. (2000) Using Habermas to Evaluate Two Approaches to Negotiated Assessment. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 25, 3, 293-304 Habermas, J (1971) Knowledge and Human Interests. London: Heineman Hager, P. (2000) Knowledge that Works: Judgement and the University Curriculum, in Symes, C. and McIntyre, J. (eds.) (2000) pp. 47-65 Harrison, R. (2000) Learner Managed Learning: Managing to Learn or Learning to Manage? International Journal of Lifelong Education, 19, 4, 312321 Hart, M. (1990) Critical Theory and Beyond: Further Perspectives on Emancipatory Education. Adult Education Quarterly, 40, 3, 125-138 Harvey, L. & Knight, P. (1996) Transforming Higher Education. Buckingham: SRHE/OUP Holmes, L. (2000) What can performance tell us about learning? Explicating a troubled concept. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 9, 2, 253-266 37 Hyland, T. & Johnson, S. (1998) Of Cabbages and Key Skills: exploding the mythology of core transferable skills in post-school education. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 22, 2, 163-172. Illich, I. (1971) Deschooling Society. London: Calder and Boyars Improvements Development Agency (2001). The Local Government Improvement Programme 1999-2000. http://www.idea.gov.uk Kemmis, S (1985) Action research and the politics of reflection, in D. Boud, R. Keogh & D. Walker, Reflection: Turning Experience into Learning London: Kogan Page King, P. & Kitchener, K (1994) Developing Reflective Judgement. San Francisco: Jossey Bass Knowles, M.S. and Associates (1986) Using Learning Contracts. San Francisco: Jossey Bass Knowles, M.S. (1980) The modern practice of adult education (rev. ed.) Chicago: Follet Knowles, M. S. (1984) Androgogy in Action: applying modern principles of adult learning. San Francisco: Jossey Bass Kold, D. (1984) Experiential learning. Experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall Lash, S & Urry, J (1994) Economies of Signs and Space. London: Sage Lave, J. and Wenger, E. (1991) Situated Learning. Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge: C.U.P. Marton, F., Beaty, E. & Dall’Alba, G (1993) Conceptions of Learning. International Journal of Education Research, 19, 277-300 Marton, F., Hounsell, D. & Entwistle, N. (eds) (1984) The Experience of Learning. Edinburgh: Scottish Academic Press Maslow, A.H. (1968) Towards a Psychology of Being. 2nd ed. New York: Van Nostrand Mezirow, J., and Associates (1990) Fostering Critical Reflection in Adulthood. San Francisco: Jossey Bass Mezirow, J. (1991a) Transformative Dimensions of Adult Learning. San Francisco: Jossey Bass Mezirow, J. (1991b) Transformative Theory and Cultural Context: A Reply to Clark and Wilson. Adult Education Quarterly, 41, 3, 188-192 38 Miettinen, R. (2000) The concept of experiential learning and John Dewey’s theory of reflective thought and action. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 19,1,54-72 Moon, J.A. (2000) Reflection in Learning and Professional Development. London: Kogan Page National Committee of Enquiry into Higher Education (1997). Higher Education in the Learning Society, London:SO Neave, G. (2000), Diversity, differentiation and the market: the debate we never had but which we ought to have done. Higher Education Policy 13, 7-12 Newman, J (2000), Beyond the New Public Management? Modernising Public Services in New Managerialism, New Welfare? Clarke, J.,Gerwitz, S., McLaughlin, E. (eds) London:OUP/Sage Norris, N (1991) The Trouble with Competence. Cambridge Journal of Education, 21, 3, 331-341 Ramsden, P. (ed) (1988) Improving Learning: New Perspectives. London: Kogan Page Ranson, S. ed. (1998) Inside the Learning Society. London: Cassell Rogers, C. (1978) Carl Rogers on Personal Power. London: Constable Ryle, G. (1949) The Concept of Mind, London: Hutchinson Saljo, R. (1982) Learning and Understanding: A Study of Differences in Constructing Meaning from a Text. Gothenburg: Acta Universitatis Gothenburgensis Schon, D. (1971) Beyond the Stable State. London: Maurice Temple Smith Schon, D (1983) The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. New York: Basic Books Schuller, T, Bynner, J., Green, A., Blackwell, C, Hammond, C., Preston, J &Gough, M (2001) Modelling and Measuring the Wider Benefits of Learning. Publication pending: Institute of Education, Birkbeck, London Stephenson, J. (1993) The Student Experience of Independent Study: Reaching the parts other programmes appear to miss, in N. Graves (ed.) Learner Managed Learning. London: HEC Tarrant, J (2000) What is Wrong with Competence? Journal of Further and Higher Education, 24, 1, 77-83 39 Taylor, E.W. (2001) The Theory and Practice of Transformative Learning: a critical review. http://www.ericacve.org/majorpubs.2asp?ID=16. Information series no. 374 Tennant, M. C. (1993) Perspective Transformation and Adult Development. Adult Education Quarterly, 44, 1, 34-42 Tough, A. (1979) The Adults’ Learning Projects: A Fresh Approach to Theory and Practice in Adult Education. Toronto: Ontario Institute for Studies in Education Usher, R.(1985) Beyond the anecdotal: adult learning and the use of experience. Studies in the Education of Adults, 17, 1, 59-74 Usher, R. S. & Solomon, N (1998) Experiential learning and the shaping of subjectivity in the workplace. Paper presented to the 6th International Conference on Experiential Learning (ICEL), ‘Experiential Learning in the Context of Lifelong Learning’, Tampere University, Finland, 2-5 July Van Manen, M. (1977) Linking ways of knowing and ways of being. Curriculum Inquiry, 6, 205-208 Van Manen, M. (1991) The Tact of Teaching. New York: The State of New York Press 40 41