Reading skills for academic study: Understanding text structure

advertisement

Reading skills for academic study

A. Reading skills for academic study: Understanding text structure

http://www.uefap.com/reading/readfram.htm

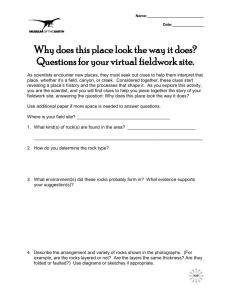

Exercise 1

Look at the structure of the following text.

The Personal Qualities of a Teacher

1. Here I want to try to give you an answer to the question: What personal qualities are desirable

in a teacher? Probably no two people would draw up exactly similar lists, but I think the

following would be generally accepted.

2. First, the teacher’s personality should be pleasantly live and attractive. This does not rule out

people who are physically plain, or even ugly, because many such have great personal charm.

But it does rule out such types as the over-excitable, melancholy, frigid, sarcastic, cynical,

frustrated, and over-bearing : I would say too, that it excludes all of dull or purely negative

personality. I still stick to what I said in my earlier book: that school children probably ‘suffer

more from bores than from brutes’.

3. Secondly, it is not merely desirable but essential for a teacher to have a genuine capacity for

sympathy - in the literal meaning of that word; a capacity to tune in to the minds and feelings

of other people, especially, since most teachers are school teachers, to the minds and feelings

of children. Closely related with this is the capacity to be tolerant - not, indeed, of what is

wrong, but of the frailty and immaturity of human nature which induce people, and again

especially children, to make mistakes.

4. Thirdly, I hold it essential for a teacher to be both intellectually and morally honest. This does

not mean being a plaster saint. It means that he will be aware of his intellectual strengths, and

limitations, and will have thought about and decided upon the moral principles by which his

life shall be guided. There is no contradiction in my going on to say that a teacher should be a

bit of an actor. That is part of the technique of teaching, which demands that every now and

then a teacher should be able to put on an act - to enliven a lesson, correct a fault, or award

praise. Children, especially young children, live in a world that is rather larger than life.

5. A teacher must remain mentally alert. He will not get into the profession if of low intelligence,

but it is all too easy, even for people of above-average intelligence, to stagnate intellectually and that means to deteriorate intellectually. A teacher must be quick to adapt himself to any

situation, however improbable and able to improvise, if necessary at less than a moment’s

notice. (Here I should stress that I use ‘he’ and ‘his’ throughout the book simply as a matter of

convention and convenience.)

6. On the other hand, a teacher must be capable of infinite patience. This, I may say, is largely a

matter of self-discipline and self-training; we are none of us born like that. He must be pretty

resilient; teaching makes great demands on nervous energy. And he should be able to take in

his stride the innumerable petty irritations any adult dealing with children has to endure.

7. Finally, I think a teacher should have the kind of mind which always wants to go on learning.

Teaching is a job at which one will never be perfect; there is always something more to learn

about it. There are three principal objects of study: the subject, or subjects, which the teacher

is teaching; the methods by which they can best be taught to the particular pupils in the classes

he is teaching; and - by far the most important - the children, young people, or adults to whom

they are to be taught. The two cardinal principles of British education today are that education

is education of the whole person, and that it is best acquired through full and active cooperation between two persons, the teacher and the learner.

(From Teaching as a Career, by H. C. Dent)

1

Reading skills for academic study

Notice how the text is structured. Paragraph 1 asks a question and paragraphs 2 - 7 answer it.

Question What are the desirable personal qualities in a teacher?

Answer

paragraph 1

Quality 1. personality should be pleasantly live and attractive

paragraph 2

Quality 2. essential to have a genuine capacity for sympathy

paragraph 3

Quality 3. essential to be both intellectually and morally honest

paragraph 4

Quality 4. must remain mentally alert

paragraph 5

Quality 5. must be capable of infinite patience

paragraph 6

Quality 6. should have the kind of mind which always wants to go on

paragraph 7

learning

Exercise 2

Look at the structure of the following text.

The Rules of Good Fieldwork

1. In my sketch of an anthropologist's training, I have only told you that he must make intensive

studies of primitive peoples. I have not yet told you how he makes them. How does one make

a study of a primitive people? I will answer this question very briefly and in very general

terms, stating only what we regard as the essential rules of good fieldwork.

2. Experience has proved that certain conditions are essential if a good investigation is to be

carried out. The anthropologist must spend sufficient time on the study, he must throughout be

in close contact with the people among whom he is working, he must communicate with them

solely through their own language, and he must study their entire culture and social life. I will

examine each of these desiderata for, obvious though they may be, they are the distinguishing

marks of British anthropological research which make it, in my opinion, different from and of

a higher quality than research conducted elsewhere.

3. The earlier professional fieldworkers were always in a great hurry. Their quick visits to native

peoples sometimes lasted only a few days, and seldom more than a few weeks. Survey

research of this kind can be a useful preliminary to intensive studies and elementary

ethnological classifications can be derived from it, but it is of little value for an understanding

of social life. The position is very different today when, as I have said, one to three years are

devoted to the study of a single people. This permits observations to be made at every season

of the year, the social life of the people to be recorded to the last detail, and conclusions to be

tested systematically.

4. However, given even unlimited time for research, the anthropologist will not produce a good

account of the people he is studying unless he can put himself in a position which enables him

to establish ties of intimacy with them, and to observe their daily activities from within, and

not from without, their community life.

5. He must live as far as possible in their villages and camps, where he is, again as far as

possible, physically and morally part of the community. He then not only sees and hears what

goes on in the normal everyday life of the people as well as less common events, such as

ceremonies and legal cases, but by taking part in those activities in which he can appropriately

engage, he learns through action as well as by ear and eye what goes on around him. This is

very unlike the situation in which records of native life were corn-piled by earlier

anthropological fieldworkers, and also by missionaries and administrators, who, living out of

the native community and in mission stations or government posts, had mostly to rely on what

a few informants told them. If they visited native villages at all, their visits interrupted and

changed the activities they had come to observe.

2

Reading skills for academic study

6. What is perhaps even more important for the anthropologist's work is the fact that he is all

alone, cut off from the companionship of men of his own race and culture, and is dependent on

the natives around him for company, friendship, and human under-standing. An anthropologist

has failed unless, when he says good-bye to the natives, there is on both sides the sorrow of

parting. It is evident that he can only establish this intimacy if he makes himself in some

degree a member of their society and lives, thinks, and feels in their culture since only he, and

not they, can make the necessary transference.

7. It is obvious that if the anthropologist is to carry out his work in the conditions I have

described he must learn the native language, and any anthropologist worth his salt will make

the learning of it his first task and will altogether, even at the beginning of his study, dispense

with interpreters. Some do not pick up strange languages easily, and many primitive languages

are almost unbelievably difficult to learn, but the language must be mastered as thoroughly as

the capacity of the student and its complexities permit, not only because the anthropologist can

then communicate freely with the natives, but for further reasons. To understand a people's

thought one has to think in their symbols. Also, in learning the language one learns the culture

and the social system which are conceptualized in the language. Every kind of social

relationship, every belief every technological process - in fact everything in the social life of

the natives - is expressed in words as well as in action, and when one has fully understood the

meaning of all the words of their language in all their situations of reference one has finished

one's study of the society. I may add that, as every experienced field-worker knows, the most

difficult task in anthropological fieldwork is to determine the meanings of a few key words,

upon which the success of the whole investigation depends; and they can only be determined

by the anthropologist himself learning to use the words correctly in his converse with the

natives. A further reason for learning the native language is that it places the anthropologist in

a position of complete dependence on the natives. He comes to them as pupil, not as master.

8. Finally, the anthropologist must study the whole of the social life. It is impossible to

understand clearly and comprehensively any part of a people's social life except in the full

context of their social life as a whole. Though he may not publish every detail he has recorded,

you will find in a good anthropologist's notebooks a detailed description of even the most

commonplace activities, for example, how a cow is milked or how meat is cooked. Also,

though he may decide to write a book on a people's law, or their religion, or on their

economics, describing one aspect of their life and neglecting the rest, he does so always

against the background of their entire social activities and in terms of their whole social

structure.

(From Social Anthropology, by E. E. Evans-Pritchard.)

Notice how the text is structured. Paragraph 1 asks a question and paragraphs 2 - 8 answer it.

Question how one makes a study of a primitive people - essential rules paragraph 1

1. must spend sufficient time on the study

paragraphs 2 and 3

2. must establish ties of intimacy

paragraph 4

3. must live as far as possible in their villages and camps

paragraph 5

4. must make oneself a member of their society

paragraph 6

5. must learn the native language

paragraph 7

6. must study the whole of the social life.

paragraph 8

Answer

3

Reading skills for academic study

Exercise 3

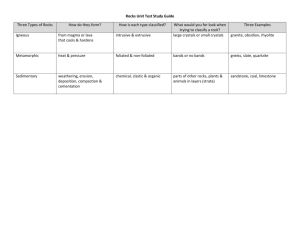

Read the following text and observe the table below.

Making Artificial Diamonds

1. 'It should be possible to make a precious stone that not only looks like the real thing, but that

is the real thing', said a chemist many years ago. 'The only difference should be that one

crystal would be made by man, the other by nature.'

2. At first this did not seem like a particularly hard task. Scientists began to try making synthetic

diamonds towards the end of the eighteenth century. It was at this time that a key scientific

fact was discovered: diamonds are a form of carbon, which is a very common element.

Graphite, the black mineral that is used for the 'lead' in your pencil, is made of it, too. The

only difference, we know today, is that the carbon atoms have been packed together in a

slightly different way. The chemists were fired with enthusiasm: Why not change a cheap and

plentiful substance, carbon, into a rare and expensive one, diamond?

3. You have probably heard about the alchemists who for centuries tried to turn plain lead or iron

into gold. They failed, because gold is completely different from lead or iron. Transforming

carbon into diamonds, however, is not illogical at all. This change takes place in nature, so it

should be possible to make it happen in the laboratory.

4. It should be possible, but for one hundred and fifty years every effort failed. During this

period, none the less., several people believed that they had solved the diamond riddle. One of

these was a French scientist who produced crystals that seemed to be the real thing. After the

man's death, however, a curious rumour began to go the rounds. The story told that one of the

scientist's assistants had simply put tiny pieces of genuine diamonds into the carbon mixture.

He was bored with the work, and he wanted to make the old chemist happy.

5. The first real success came more than sixty years later in the laboratories of the General

Electric Company. Scientists there had been working for a number of years on a process

designed to duplicate nature's work. Far below the earth's surface, carbon is subjected to

incredibly heavy pressure and extremely high temperature. Under these conditions the carbon

turns into diamonds. For a long time the laboratory attempts failed, simply because no suitable

machinery existed. What was needed was some sort of pressure chamber in which the carbon

could be subjected to between 800,000 and 1,800,000 pounds of pressure to the square inch, at

a temperature of between 2200 and 4400�F.

6. Building a pressure chamber that would not break under these conditions was a fantastically

difficult feat, but eventually it was done. The scientists eagerly set to work again. Imagine

their disappointment when, even with this equipment, they produced all sorts of crystals, but

no diamonds. They wondered if the fault lay in the carbon they were using, and so they tried a

number of different forms.

7. 'Every time we opened the pressure chamber we found crystals. Some of them even had the

smell of diamonds', recalls one of the men who worked on the project. 'But they were terribly

small, and the tests we ran on them were unsatisfactory.'

8. The scientists went on working. The idea was then brought forward that perhaps the carbon

needed to be dissolved in a melted metal. The metal might act as a catalyst, which means that

it helps a chemical reaction to take place more easily.

9. This time the carbon was mixed with iron before being placed in the pressure chamber. The

pressure was brought up to 1,300,000 pounds to the square inch and the temperature to

2900�F. At last the chamber was opened. A number of shiny crystals lay within. These

crystals scratched glass, and even diamonds. Light waves passed through them in the same

way as they do through diamonds. Carbon dioxide was given off when the crystals were

burned. Their density was just 3.5 grams per cubic centimetre, as is true of diamonds. The

crystals were analysed chemically. They were finally studied under X-rays, and there was no

longer room for doubt. These jewels of the laboratory were not like diamonds ; they were

4

Reading skills for academic study

diamonds. They even had the same atomic structure. The atoms making up the molecule of the

synthetic crystal were arranged in exactly the same pattern as they are in the natural.

10. 'The jewels we have made are diamonds', says a physicist, 'but they are not very beautiful.

Natural diamonds range in colour from white to black, with the white or blue-white favoured

as gems. Most of ours are on the dark side, and are quite small.'

(From The Artificial World Around Us by Lucy Kavaler)

^

Problem

How to make artificial diamonds.

Paragraph 1

Theoretical Background Diamonds are a form of carbon and carbon is easily available Paragraph 2

Early attempts

Paragraph 3

Failure

Paragraph 4

Failure - need more pressure

Paragraph 5

Failure - produced crystals but not diamonds

Paragraph 6

Failure - too small

Paragraph 7

Solution

Solution - need a catalyst

Paragraph 8

Success

Success - artificial damonds made

Paragraph 9

Evaluation

But ...

Paragraph 10

Attempts

Exercise 4

Read the following text and fill in the table below.

An observation and an explanation

It is worth looking at one or two aspects of the way a mother behaves towards her baby. The usual

fondling, cuddling and cleaning require little comment, but the position in which she holds the baby

against her body when resting is rather revealing. Careful American studies have disclosed the fact

that 80 per cent of mothers cradle their infants in their left arms, holding them against the left side of

their bodies. If asked to explain the significance of this preference most people reply that it is

obviously the result of the predominance of right-handedness in the population. By holding the babies

in their left arms, the mothers keep their dominant arm free for manipulations. But a detailed analysis

shows that this is not the case. True, there is a slight difference between right-handed and left-handed

females, but not enough to provide an adequate explanation. It emerges that 83 per cent of righthanded mothers hold the baby on the left side, but then so do 78 per cent of left-handed mothers. In

other words, only 22 per cent of the left-handed mothers have their dominant hands free for actions.

Clearly there must be some other, less obvious explanation.

The only other clue comes from the fact that the heart is on the left side of the mother's body. Could it

be that the sound of her heartbeat is the vital factor? And in what way? Thinking along these lines it

was argued that perhaps during its existence inside the body of the mother, the growing embryo

becomes fixated ('imprinted') on the sound of the heart beat. If this is so, then the re-discovery of this

familiar sound after birth might have a calming effect on the infant, especially as it has just been thrust

into a strange and frighteningly new world outside. If this is so then the mother, either instinctively or

by an unconscious series of trials and errors, would soon arrive at the discovery that her baby is more

at peace if held on the left against her heart, than on the right.

This may sound far-fetched, but tests have now been carried out which reveal that it is nevertheless the

true explanation. Groups of new-born babies in a hospital nursery were exposed for a considerable

time to the recorded sound of a heartbeat at a standard rate of 72 beats per minute. There were nine

babies in each group and it was found that one or more of them was crying for 60 per cent of the time

5

Reading skills for academic study

when the sound was not switched on, but that this figure fell to only 38 per cent when the heartbeat

recording was thumping away. The heartbeat groups also showed a greater weight-gain than the

others, although the amount of food taken was the same in both cases. Clearly the beatless groups

were burning up a lot more energy as a result of the vigorous actions of their crying.

Another test was done with slightly older infants at bedtime. In some groups the room was silent, in

others recorded lullabies were played. In others a ticking metronome was operating at the heartbeat

speed of 72 beats per minute. In still others the heartbeat recording itself was played. It was then

checked to see which groups fell asleep more quickly. The heartbeat group dropped off in half the time

it took for any of the other groups. This not only clinches the idea that the sound of the heart beating is

a powerfully calming stimulus, but it also shows that the response is a highly specific one. The

metronome imitation will not do - at least, not for young infants.

So it seems fairly certain that this is the explanation of the mother's left-side approach to baby-holding.

It is interesting that when 466 Madonna and child paintings (dating back over several hundred years)

were analysed for this feature, 373 of them showed the baby on the left breast. Here again the figure

was at the 80 per cent level. This contrasts with observations of females carrying parcels, where it was

found that 50 per cent carried them on the left and 50 per cent on the right.

What other possible results could this heartbeat imprinting have? It may, for example, explain why we

insist on locating feelings of love in the heart rather than the head. As the song says: 'You gotta have a

heart!' It may also explain why mothers rock their babies to lull them to sleep. The rocking motion is

carried on at about the same speed as the heartbeat, and once again it probably 'reminds' the infants of

the rhythmic sensations they became so familiar with inside the womb, as the great heart of the mother

pumped and thumped away above them.

Nor does it stop there. Right into adult life the phenomenon seems to stay with us. We rock with

anguish. We rock back and forth on our feet when we are in a state of conflict. The next time you see a

lecturer or an after-dinner speaker swaying rhythmically from side to side, check his speed for

heartbeat time. His discomfort at having to face an audience leads him to perform the most comforting

movements his body can offer in the somewhat limited circumstances; and so he switches on the old

familiar beat of the womb.

Wherever you find insecurity, you are liable to find the comforting heartbeat rhythm in one kind of

disguise or another. It is no accident that most folk music and dancing has a syncopated rhythm. Here

again the sounds and movements take the performers back to the safe world of the womb.

(From The Naked Ape by Desmond Morris. (Jonathan Cape and McGraw Hill, 1967)

Paragraph

1

Paragraph

2

Problem

________________________________

_____________

Most women are right-handed.

_____________

_________________________________

Solution 2

_________________________________

_______________

1. Groups of new-born babies exposed to sound of heart beat

__________________.

2. Three groups of older babies listend to different sounds.

_____________________.

3.

Even

in

old

paintings,

_______________________________________________.

4.

When

observed

carrying

parcels,

______________________________________.

Other

consequences

1.

2.

3.

Paragraph

3

Paragraph

4

Paragraph

5

Paragraph

6

Paragraph

We

locate

Mothers

We

rock

6

love

_________________________.

______________________________.

______________________________.

Reading skills for academic study

7

4. Folk music and dancing ___________________.

Paragraph

8

B. Reading skills for academic study: Understanding conceptual meaning

Exercise 1

Read each of the following paragraphs. Decide which rhetorical structures are used.

1. DIVISIONS OF GEOLOGICAL TIME

The rocks of the accessible part of the earth are divided into five major divisions or eras, which are in

the order of decreasing age, Archeozoic, Proterozoic, Paleozoic, Mesozoic, and Cenozoic.

Superposition is the criterion of age. Each rock is considered younger than the one on which it rests,

provided there is no structural evidence to the contrary, such as overturning or thrust faulting. As one

looks at a tall building there is no doubt in the mind of the observer that the top story was erected after

the one on which it rests and is younger than it in order of time. So it is in stratigraphy in which strata

are arranged in an orderly sequence based upon their relative positions. Certainly the igneous and

metamorphic rocks at the bottom of the Grand Canyon are the oldest rocks exposed along the

Colorado River in Arizona and each successively higher formation is relatively younger than the one

beneath it.

2. There are two traditional theories of forgetting. One argues that the memory trace simply fades or

decays away rather as a notice that is exposed to sun and rain will gradually fade until it becomes quite

illegible. The second suggests that forgetting occurs because memory traces are disrupted or obscured

by subsequent learning, or in other words that forgetting occurs because of interference. How can one

decide between these two interpretations of forgetting? If the memory trace decays spontaneously,

then the crucial factor determining how much is recalled should simply be elapsed time. The longer

the delay, the greater the forgetting. If forgetting results from interference however then the crucial

factor should be the events that occur within that time, with more interpolated events resulting in more

forgetting.

3. WEATHERING AND SOIL. The work of weathering is carried on mainly by the atmosphere,

which affects rocks physically and chemically. Disintegration of rocks into fragments having the same

chemical composition as the main mass is a physical change. The chief agents of disintegration are

frost, temperature change, organ-isms, wind, rain, and lightning. Almost every rock contains some

cracks or pore space, and moisture entering the openings freezes when the temperature is below 32�F.

The change of water to ice is accompanied by an increase of volume of one tenth and by a pressure of

several tons to the square foot. Repeated freezing and expansion followed by thawing break rocks into

chips or blocks, which accumulate on the surface to form mantle rock. Wide variation in daily

temperature combined with other weathering agents causes exfoliation or scaling off of thin slabs of

rocks. Since rocks are poor conductors of heat, rays from the sun penetrate only a slight distance into

the rock, causing this outer heated part to expand. In the night it cools and contracts. Repeated

expansion and contraction weaken the outer layer, but whether the scaling off is due to this or to

moisture is debatable. The effect is greatly increased when a shower of rain falls suddenly on the

heated rock, for many of us have observed that when water is poured on hot rocks around a campfire

they often break open with great violence. Talus is composed of rock fragments broken from cliffs or

steep Slopes by frost action or temperature change, and is moved by gravity down the slope until its

surface approaches the angle of repose of loose materials. Organisms of various kinds are active

instruments of disintegration. Plants extend a network of roots into the cracks which penetrate the

rocks in all directions. These roots enlarge during growth and act as wedges to force the rocks apart.

This wedging force not only lifts blocks of sidewalk and breaks pavements in a few years but also

7

Reading skills for academic study

disrupts natural exposures on a grand scale. Wind blows sand grains against the surface of rocks with

such force that pits of varying sizes are formed. The Sphinx and pyramids of Egypt are deeply pitted

by sand blown over northern Africa. Particles of loosened rock, removed by the next gust of wind,

become the tools for further abrasion. Sand-blasting is a commercially practical method of polishing

and cleaning rocks, including the hard surface of granite. In nature fantastic forms are sculptured by

wind abrasion, especially where materials of different degrees of resistance are in contact. In this way

balanced rocks are formed where drifting sand wears away the softer, less consolidated materials at the

base of a well-cemented layer. Likewise mushroom rocks are carved out of sandy rocks be-cause the

rock material of the stem yields more readily to the impact of sand grains than that of the top. Rain and

lightning are less effective than the other mechanical agents but contribute their share to the process of

reducing a mass of solid rock at the surface to fragments.

4. The Maasai are pastoralists, grazing their cattle over the plains which border Kenya and Tanzania.

The status of a Maasai man is directly related to the number and quality of the cattle he owns which,

traditionally, he would never sell. A Maasai woman, however, has control over housing. When she

marries, her first task is to build her own house, helped by other women in the homestead. This house

belongs to her and no one may enter without her permission. Throughout her life she will build a new

house every ten years or so.

5. American medical technology is the best on earth, but its health-care system is the most wasteful.

Americans spend roughly twice as much on doctors, drugs and snazzy brain scanners as Europeans,

but live no longer. In contrast to the all-inclusiveness of other countries' socialised medical services,

40m Americans have no coverage at all. Chinese children are more likely to be vaccinated against

disease than Americans, despite the fact that health spending per head in the United States is about 150

times higher. The government, many Americans agree, should do something. Sadly, most of their

politicians have misdiagnosed the ailment and are proposing a battery of quack remedies.AMERICAN

medical technology is the best on earth, but its health-care system is the most wasteful. Americans

spend roughly twice as much on doctors, drugs and snazzy brain scanners as Europeans, but live no

longer. In contrast to the all-inclusiveness of other countries' socialised medical services, 40m

Americans have no coverage at all. Chinese children are more likely to be vaccinated against disease

than Americans, despite the fact that health spending per head in the United States is about 150 times

higher. The government, many Americans agree, should do something. Sadly, most of their politicians

have misdiagnosed the ailment and are proposing a battery of quack remedies.

6. Woodleigh Bolton was a straggling village set along the side ofa hill. Galls Hill was the highest

house just at the top ofthe rise, with a view over Woodleigh Camp and the moors towards the sea. The

house itselfwas bleak and obviously Dr. Kennedy scorned such modern innovations as central heating.

The woman who opened the door was dark and rather forbidding. She led them across the rather bare

hail and into a study where Dr. Kennedy rose to receive them. It was a long, rather high room, lined

with well-filled bookshelves.

7. Blood Type, in medicine, is the classification of red blood cells by the presence of specific

substances on their surface. Typing of red blood cells is a prerequisite for blood transfusion. In the

early part of the 20th century, physicians discovered that blood transfusions often failed because the

blood type of the recipient was not compatible with that of the donor. In 1901 the Austrian pathologist

Karl Landsteiner classified blood types and discovered that they were transmitted by Mendelian

heredity. The four blood types are known as A, B, AB, and O. Blood type A contains red blood cells

that have a substance A on their surface. This type of blood also contains an antibody directed against

substance B, found on the red cells of persons with blood type B. Type B blood contains the reverse

combination. Serum of blood type AB contains neither antibody, but red cells in this type of blood

contain both A and B substances. In type O blood, neither substance is present on the red cells, but the

individual is capable of forming antibodies directed against red cells containing substance A or B. If

blood type A is transfused into a person with B type blood, anti-A antibodies in the recipient will

destroy the transfused A red cells. Because O type blood has neither substance on its red cells, it can

be given successfully to almost any person. Persons with blood type AB have no antibodies and can

8

Reading skills for academic study

receive any of the four types of blood; thus blood types O and AB are called universal donors and

universal recipients, respectively. Other hereditary blood-group systems have subsequently been

discovered. The hereditary blood constituent called Rh factor is of great importance in obstetrics and

blood transfusions because it creates reactions that can threaten the life of newborn infants. Blood

types M and N have importance in legal cases involving proof of paternity.

8. An atomic bomb is a powerful explosive nuclear weapon fueled by the splitting, or fission, of the

nuclei of specific isotopes of uranium or plutonium in a chain reaction. The strength of the explosion

created by an atomic bomb is on the order of the strength of the explosion that would be created by

thousands of tons of TNT. An atomic bomb must provide enough mass of plutonium or uranium to

reach critical mass, the mass at which the nuclear reactions going on inside the material can make up

for the neutrons leaving the material through its outside surface. Usually the plutonium or uranium in a

bomb is separated into parts so that critical mass is not reached until the bomb is set to explode. At

that point, a set of chemical explosives or some other mechanism drives all the different pieces of

uranium or plutonium together to produce a critical mass. After this occurs, there are enough neutrons

bouncing around in the material to create a chain reaction of fissions. In the fission reactions,

collisions between neutrons and uranium or plutonium atoms cause the atoms to split into pairs of

nuclear fragments, releasing energy and more neutrons. Once the reactions begin, the neutrons

released by each reaction hit other atoms and create more fission reactions until all the fissile material

is exhausted or scattered.

9. Atomic tests

The first atomic explosion was conducted, as a test, at Alamogordo, New Mexico, on July 16, 1945.

The energy released from this explosion was equivalent to that released by the detonation of 20,000

tons of TNT. Near the end of World War II, on August 6, 1945, the United States dropped the first

atomic bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima. It followed with a second bomb against the city of

Nagasaki on August 9. As many as 100,000 persons were killed by the Hiroshima device, called

"Little Boy," and about 40,000 by a bomb dropped on Nagasaki, called "Fat Man." Japan agreed to

U.S. terms of surrender on August 14th. These are the only times that a nuclear weapon has been used

in a conflict between nations.

10. Aaron Copland was an American composer. He was born in New York City on November 14,

1900. He studied in New York City with the American composer Rubin Goldmark and in Paris with

the influential French teacher Nadia Boulanger. Although his earliest work was heavily influenced by

the French impressionists, he soon began to develop a personalized style. After experimenting with

jazz rhythms in such works as Music for the Theater (1925) and the Piano Concerto (1927), Copland

turned to more austere and dissonant compositions. Concert pieces such as the Piano Variations (1930)

and Statements (1933-1935) rely on nervous, irregular rhythms, angular melodies, and highly

dissonant harmonies. In the mid-1930s Copland turned to a simpler style, more melodic and lyrical,

frequently drawing on elements of American folk music. His best work of the 1940s expresses

distinctly American themes; in Lincoln Portrait (1942), for orchestra and narrator, and in the ballets

Billy the Kid (1938), Rodeo (1942), and Appalachian Spring (1944; Pulitzer Prize, 1945), he uses

native themes and rhythms to capture the flavor of early American life. He adapted Mexican folk

music for El sal�n M�xico (1937). Other orchestral works are the Symphony for Organ and

Orchestra (1925), the Symphonic Ode (1932), and the Third Symphony (1946), which incorporates the

Fanfare for the Common Man (1942). Also from this period is the opera for high school students, The

Second Hurricane (1937). His music for films includes Of Mice and Men (1937), Our Town (1940),

and The Heiress (1949; Academy Award, best dramatic film score). In the 1950s Copland returned to

his earlier austere style. In the complex, virtuosic Piano Fantasy (1957) and such later orchestral works

as Connotations (1962), commissioned for the opening of Lincoln Center in New York City, and

Inscape (1967), he assimilated the twelve-tone system of composition. Copland's Proclamation (1982),

a piano piece orchestrated by Phillip Ramey, was performed in 1985 at a concert celebrating Copland's

85th birthday. Copland died in North Tarrytown, New York, on December 2, 1990.

9

Reading skills for academic study

C. Reading skills for academic study: Identifying reference in the text

C.1. Reference

Identify the references in the following texts:

Exercise 1

Every organization, as soon as it gets to any size (perhaps 1,000 people), begins to feel a need to

systematize its management of human assets. Perhaps the pay scales have got way out of line, with

apparently similar-level jobs paying very different amounts; perhaps there is a feeling that there are a

lot of neglected skills in the organization that other departments could utilize if they were aware that

they existed. Perhaps individuals have complained that they don't know where they stand or what their

future is; perhaps the unions have requested standardized benefits and procedures. Whatever the

historical origins, some kind of central organization, normally named a personnel department, is

formed to put some system into the haphazardry. The systems that they adopt are often modelled on

the world of production, because that is the world with the best potential for order and system.

Exercise 2

We all tend to complain about our memories. Despite the elegance of the human memory system, it is

not infallible, and we have to learn to live with its fallibility. It seems to be socially much more

acceptable to complain of a poor memory, and it is somehow much more acceptable to blame a social

lapse on 'a terrible memory', than to attribute it to stupidity or insensitivity. But how much do we

know about our own memories? Obviously we need to remember our memory lapses in order to know

just how bad our memories are. Indeed one of the most amnesic patients I have ever tested was a lady

suffering from Korsakoff's syndrome, memory loss following chronic alcoholism. The test involved

presenting her with lists of words; after each list she would comment with surprise on her inability to

recall the words, saying: 'I pride myself on my memory!' She appeared to have forgotten just how bad

her memory was'.

C.2. Substitution and ellipsis

Identify examples of substitution and ellipsis in this text:

Exercise 3

The human memory system is remarkably efficient, but it is of course extremely fallible. That being

so, it makes sense to take full advantage of memory aids to minimize the disruption caused by such

lapses. If external aids are used, it is sensible to use them consistently and systematically - always put

appointments in your diary, always add wanted items to a shopping list, and so on. If you use internal

aids such as mnemonics, you must be prepared to invest a reasonable amount of time in mastering

them and practising them. Mnemonics are like tools and cannot be used until forged. Overall,

however, as William James pointed out (the italics are mine): 'Of two men with the same outward

experiences and the same amount of mere native tenacity, the one who thinks over his experiences

most and weaves them into systematic relations with each other will be the one with the best memory.'

Exercise 4

This conflict between tariff reformers and free traders was to lead to the "agreement to differ"

convention in January 1932, and the resignation of the Liberals from the government in September

1932; but, until they resigned, the National Government was a genuine coalition in the sense in which

that term is used on the continent: a government comprising independent yet conflicting elements

allied together, a government within which party conflict was not superseded but rather contained - in

short, a power-sharing government, albeit a seriously unbalanced one.

10

Reading skills for academic study

Exercise 5

The number of different words relating to 'camel' is said to be about six thousand. There are terms to

refer to riding camels, milk camels and slaughter camels; other terms to indicate the pedigree and

geographical origin of the camel; and still others to differentiate camels in different stages of

pregnancy and to specify in-numerable other characteristics important to a people so dependent upon

camels in their daily life (Thomas, 1937)

Exercise 6

There were, broadly, two interrelated reasons for this, the first relating to Britain's economic and

Imperial difficulties, the second to the internal dissension in all three parties.

C.3. Conjunction

Identify examples of conjunction in the following texts:

Exercise 7

These two forms of dissent coalesced in the demand for a stronger approach to the Tory nostrum of

tariff reform. In addition, trouble threatened from the mercurial figure of Winston Churchill, who had

resigned from the Shadow Cabinet in January 1931 in protest at Baldwin's acceptance of eventual selfgovernment for India.

Exercise 8

These two sets of rules, though distinct, must not be looked upon as two co-ordinate and independent

systems. On the contrary, the rules of Equity are only a sort of supplement or appendix to the Common

Law; they assume its existence but they add something further.

C.4. Lexical cohesion

Identify examples of lexical cohesion in the following texts:

Exercise 9

The clamour of complaint about teaching in higher education and, more especially, about teaching

methods in universities and technical colleges, serves to direct attention away from the important

reorientation which has recently begun. The complaints, of course, are not unjustified. In dealing

piece-meal with problems arising from rapidly developing subject matter, many teachers have allowed

courses to become over-crowded, or too specialized, or they have presented students with a number of

apparently unrelated courses failing to stress common principles. Many, again, have not developed

new teaching methods to deal adequately with larger numbers of students, and the new audio-visual

techniques tend to remain in the province of relatively few enthusiasts despite their great potential for

class and individual teaching.

Exercise 10

When we look closely at a human face we are aware of many expressive details - the lines of the

forehead, the wideness of the eyes, the curve of the lips, the jut of the chin. These elements combine to

present us with a total facial expression which we use to interpret the mood of our companion. But we

all know that people can 'put on a happy face' or deliberately adopt a sad face without feeling either

happy or sad. Faces can lie, and sometimes can lie so well that it becomes hard to read the true

emotions of their owners. But there is at least one facial signal that cannot easily be 'put on'. It is a

small signal, and rather a subtle one, but because it tells the truth it is of special interest. It comes from

the pupils and has to do with their size in relation to the amount of light that is falling upon them.

11

Reading skills for academic study

D. Reading skills for academic study: Identifying reference in the text

D.1. Reference

Identify the references in the following text:

Exercise 11

The Troubles of shopping in Russia

A large crowd gathered outside a photographic studio in Arbat Street, one of the busiest shopping

streets in Moscow, recently. There was no policeman within sight and the crowd was blocking the

pavement. The centre of attraction - and amusement - was a fairly well-dressed man, perhaps some

official, who was waving his arm out of the ventilation window of the studio and begging to be

allowed out. The woman in charge of the studio was standing outside and arguing with him. The man

had apparently arrived just when the studio was about to close for lunch and insisted upon taking

delivery of some prints which had been promised to him. He refused to wait so the staff had locked the

shop and gone away for lunch. The incident was an extreme example of the common attitude in

service industries in the Soviet Union generally, and especially in Moscow. Shop assistants do not

consider the customer as a valuable client but as a nuisance of some kind who has to be treated with

little ceremony and without concern for his requirements.

For nearly a decade, the Soviet authorities have been trying to improve the service facilities. More

shops are being opened, more restaurants are being established and the press frequently runs

campaigns urging better service in shops and places of entertainment. It is all to no avail. The main

reason for this is shortage of staff. Young people are more reluctant to make a career in shops,

restaurants and other such establishments. Older staff are gradually retiring and this leaves a big gap. It

is not at all unusual to see part of a restaurant or a shop roped off because there is nobody available to

serve. Sometimes, establishments have been known to be closed for several days because of this.

One reason for the unpopularity of jobs in the service industries is their low prestige. Soviet papers

and journals have reported that people generally consider most shop assistants to be dishonest and this

conviction remains unshakeable. Several directors of business establishments, for instance, who are

loudest in complaining about shortage of labour, are also equally vehement that they will not let their

children have anything to do with trade.

The greatest irritant for the people is not the shortage of goods but the time consumed in hunting for

them and queuing up to buy them. This naturally causes ill-feeling between the shoppers and the

assistants behind the counters, though often it may not be the fault of the assistants at all. This too,

damages hopes of attracting new recruits. Many educated youngsters would be ashamed to have to

behave in such a negative way.

Rules and regulations laid down by the shop managers often have little regard for logic or

convenience. An irate Soviet journalist recently told of his experiences when trying to have an electric

shaver repaired. Outside a repair shop he saw a notice: 'Repairs done within 45 minutes.' After

queuing for 45 minutes he was asked what brand of shaver he owned. He identified it and was told that

the shop only mended shavers made in a particular factory and he would have to go to another shop,

four miles away. When he complained, the red-faced girl behind the counter could only tell him

miserably that those were her instructions.

All organisations connected with youth, particularly the Young Communist League (Komsomo1),

have been instructed to help in the campaign for better recruitment to service industries. The

Komsomol provides a nicely-printed application form which is given to anyone asking for a job. But

one district head of a distribution organisation claimed that in the last in years only one person had

come to him with this form. 'We do not need fancy paper. We do need people!' he said. More and

more people are arguing that the only way to solve the problem is to introduce mechanisation. In

grocery stores, for instance, the work load could be made easier with mechanical devices to move

sacks and heavy packages.

12

Reading skills for academic study

The shortages of workers are bringing unfortunate consequences in other areas. Minor rackets flourish.

Only a few days ago, Pravda, the Communist Party newspaper, carried a long humorous feature about

a plumber who earns a lot of extra money on the side and gets gloriously drunk every night. He is

nominally in charge of looking after 300 flats and is paid for it. But whenever he has a repair job to do,

he manages to screw some more money from the flat dwellers, pretending that spare parts are required.

Complaints against him have no effect because the housing board responsible is afraid that they will

be unable to get a replacement. In a few years' time, things could be even worse if the supply of

recruits to these jobs dries up altogether.

Exercise 2

Every organization, as soon as it gets to any size (perhaps 1,000 people), begins to feel a need to

systematize its management of human assets. Perhaps the pay scales have got way out of line, with

apparently similar-level jobs paying very different amounts; perhaps there is a feeling that there are a

lot of neglected skills in the organization that other departments could utilize if they were aware that

they existed. Perhaps individuals have complained that they don't know where they stand or what their

future is; perhaps the unions have requested standardized benefits and procedures. Whatever the

historical origins, some kind of central organization, normally named a personnel department, is

formed to put some system into the haphazardry. The systems that they adopt are often modelled on

the world of production, because that is the world with the best potential for order and system.

Exercise 3

We all tend to complain about our memories. Despite the elegance of the human memory system, it is

not infallible, and we have to learn to live with its fallibility. It seems to be socially much more

acceptable to complain of a poor memory, and it is somehow much more acceptable to blame a social

lapse on 'a terrible memory', than to attribute it to stupidity or insensitivity. But how much do we

know about our own memories? Obviously we need to remember our memory lapses in order to know

just how bad our memories are. Indeed one of the most amnesic patients I have ever tested was a lady

suffering from Korsakoff's syndrome, memory loss following chronic alcoholism. The test involved

presenting her with lists of words; after each list she would comment with surprise on her inability to

recall the words, saying: 'I pride myself on my memory!' She appeared to have forgotten just how bad

her memory was'.

D.2. Substitution and ellipsis

Identify examples of substitution and ellipsis in this text:

Exercise 4

The human memory system is remarkably efficient, but it is of course extremely fallible. That being

so, it makes sense to take full advantage of memory aids to minimize the disruption caused by such

lapses. If external aids are used, it is sensible to use them consistently and systematically - always put

appointments in your diary, always add wanted items to a shopping list, and so on. If you use internal

aids such as mnemonics, you must be prepared to invest a reasonable amount of time in mastering

them and practising them. Mnemonics are like tools and cannot be used until forged. Overall,

however, as William James pointed out (the italics are mine): 'Of two men with the same outward

experiences and the same amount of mere native tenacity, the one who thinks over his experiences

most and weaves them into systematic relations with each other will be the one with the best memory.'

Exercise 5

This conflict between tariff reformers and free traders was to lead to the "agreement to differ"

convention in January 1932, and the resignation of the Liberals from the government in September

1932; but, until they resigned, the National Government was a genuine coalition in the sense in which

that term is used on the continent: a government comprising independent yet conflicting elements

allied together, a government within which party conflict was not superseded but rather contained - in

short, a power-sharing government, albeit a seriously unbalanced one.

13

Reading skills for academic study

Exercise 6

The number of different words relating to 'camel' is said to be about six thousand. There are terms to

refer to riding camels, milk camels and slaughter camels; other terms to indicate the pedigree and

geographical origin of the camel; and still others to differentiate camels in different stages of

pregnancy and to specify in-numerable other characteristics important to a people so dependent upon

camels in their daily life (Thomas, 1937)

Exercise 7

There were, broadly, two interrelated reasons for this, the first relating to Britain's economic and

Imperial difficulties, the second to the internal dissension in all three parties.

D.3. Conjunction

Identify examples of conjunction in the following texts:

Exercise 8

These two forms of dissent coalesced in the demand for a stronger approach to the Tory nostrum of

tariff reform. In addition, trouble threatened from the mercurial figure of Winston Churchill, who had

resigned from the Shadow Cabinet in January 1931 in protest at Baldwin's acceptance of eventual selfgovernment for India.

Exercise 9

These two sets of rules, though distinct, must not be looked upon as two co-ordinate and independent

systems. On the contrary, the rules of Equity are only a sort of supplement or appendix to the Common

Law; they assume its existence but they add something further.

D.3. Lexical cohesion

Identify examples of lexical cohesion in the following texts:

Exercise 10

The clamour of complaint about teaching in higher education and, more especially, about teaching

methods in universities and technical colleges, serves to direct attention away from the important

reorientation which has recently begun. The complaints, of course, are not unjustified. In dealing

piece-meal with problems arising from rapidly developing subject matter, many teachers have allowed

courses to become over-crowded, or too specialized, or they have presented students with a number of

apparently unrelated courses failing to stress common principles. Many, again, have not developed

new teaching methods to deal adequately with larger numbers of students, and the new audio-visual

techniques tend to remain in the province of relatively few enthusiasts despite their great potential for

class and individual teaching.

Exercise 11

When we look closely at a human face we are aware of many expressive details - the lines of the

forehead, the wideness of the eyes, the curve of the lips, the jut of the chin. These elements combine to

present us with a total facial expression which we use to interpret the mood of our companion. But we

all know that people can 'put on a happy face' or deliberately adopt a sad face without feeling either

happy or sad. Faces can lie, and sometimes can lie so well that it becomes hard to read the true

emotions of their owners. But there is at least one facial signal that cannot easily be 'put on'. It is a

small signal, and rather a subtle one, but because it tells the truth it is of special interest. It comes from

the pupils and has to do with their size in relation to the amount of light that is falling upon them.

14

Reading skills for academic study

E. Reading skills for academic study: Dealing with difficult words and sentences

Exercise 1

Dealing with difficult words.

In An Introduction to Language by Victoria Fromkin and Robert Rodman, many new

words are clearly explained in the text. Can you work out the meanings of the words in

bold.

AIRSTREAM MECHANISMS

The production of any speech sound (or any sound at all) involves the movement of an airstream. Most

speech sounds are produced by pushing lung air out of the body through the mouth and sometimes

also through the nose. Since lung air is used, these sounds are called pulmonic sounds; since the air is

pushed out, they are called egressive. The majority of sounds used in languages of the world are thus

produced by a pulmonic egressive airstream mechanism. All the sounds in English are produced in this

manner.

Other airstream mechanisms are used in other languages to produce sounds called ejectives,

implosives, and clicks. Instead of lung air, the body of air in the mouth may be moved. When this air

is sucked in instead of flowing out, ingressive sounds, like implosives and clicks, are produced. When

the air in the mouth is pushed out, ejectives are produced; they are thus also egressive sounds.

Word

Meaning

pulmonic

egressive

ingressive

implosives, clicks

ejectives

Exercise 2

In Time for a Tiger, a novel set in Malaysia, Anthony Burgess uses some Malay words.

Can you work out their meanings.

He watched with pleasure the food-sellers swirling the frying mee around in their kualis over primitive

charcoal fires.... Ibrahim, watching the swirling mee in the kuali, had suddenly remembered his wife....

Fatima had tracked him down and tried to hit him with a kuali in the mess kitchen.

And again:

They were sitting in a kedai in the single street of Gila, acting, it seemed, a sort of play for the entire

population of the town and the nearest kampong.

15

Reading skills for academic study

In Clockwork Orange, by the same author, he again uses non-English words. What can

you decide about their meanings?

So now, this smiling winter morning, I drink this very strong chai with moloko and spoon after spoon

after spoon of sugar, me having a sladky tooth.

And this one?

Then we slooshied the sirens and knew the millicents were coming with pooshkas pushing out of the

police auto-windows at the ready. That little weepy devotchka had told them, there being a box for

calling the rozzes not too far behind the Muni Power Plant.

Exercise 3

Read the following text. Using the context given, try to work out the meaning and the

grammatical structure of the word.

The Age of the Earth

The age of the earth has aroused the interest of scientists, clergy, and laymen. The first scientists to

attack the problem were physicists, basing their estimates on assumptions that are not now generally

accepted. G. H. Darwin calculated that 57 million years had elapsed since the moon was separated

from the earth, and Lord Kelvin estimated that 20 - 40 million years were needed for the earth to cool

from a molten condition to its present temperature. Although these estimates were much greater than

the 6,000 years decided upon some two hundred years earlier from a Biblical study, geologists thought

the earth was much older than 50 or 60 million years. In 1899 the physicist Joly calculated the age of

the ocean from the amount of sodium contained in its waters. Sodium is dissolved from rocks during

weathering and carried by streams to the ocean. Multiplying the volume of water in the ocean by the

percentage of sodium in solution, the total amount of sodium in the ocean is determined as 16

quadrillion tons. Dividing this enormous quantity by the annual load of sodium contributed by streams

gives the number of years required to deposit the sodium at the present rate. This calculation has been

checked by Clark and by Knopi with the resulting figure in round numbers of 1,000,000,000 years for

the age of the ocean. This is to be regarded as a minimum age for the earth, because all the sodium

carried by streams is not now in the ocean and the rate of deposition has not been constant. The great

beds of rock salt (sodium chloride), now stored as sedimentary rocks on land, were derived by

evaporation of salt once in the ocean. The annual contribution of sodium by streams is higher at

present than it was in past geological periods, for sodium is now released from sedimentary rocks

more easily than it was from the silicates of igneous rocks before sedimentary beds of salt were

common. Also, man mines and uses tons of salt that are added annually to the streams. These

considerations indicate that the ocean and the earth have been in existence much longer than

1,000,000,000 years, but there is no quantitative method of deciding how much the figure should be

increased. Geologists have attempted to estimate the length of geologic time from the deposition of

sedimentary rocks. This method of measuring time was recognized about 450 B.C. by the Greek

historian Herodotus after observing deposition by the Nile and realizing that its delta was the result of

repetitions of that process. Schuchert has assembled fifteen such estimates of the age of the earth

ranging from 3 to 1,584 million years with the majority falling near 100 million years. These are based

upon the known thicknesses of sedimentary rocks and the average time required to deposit one foot of

sediment. The thicknesses as well as the rates of deposition used by geologists in making these

estimates vary. Recently Schuchert has compiled for North America the known maximum thicknesses

of sedimentary rocks deposited since the beginning of Cambrian time and found them to be 259,000

feet, about 50 miles. This thickness may be increased as other information accumulates, but the real

difficulty with the method is to decide on a representative rate of deposition, because modern streams

vary considerably in the amount of sediment deposited. In past geological periods the amount

deposited may have varied even more, depending on the height of the continents above sea level, the

16

Reading skills for academic study

kind of sediment transported, and other factors. But even if we knew exact values for the thickness of

PreCambrian and PostCambrian rocks and for the average rate of deposition, the figure so obtained

would not give us the full length of time involved. At many localities the rocks are separated by

periods of erosion called unconformities, during which the continents stood so high that the products

of erosion were carried beyond the limits of the present continents and "lost intervals" of unknown

duration were recorded in the depositional record. It is also recognized that underwater breaks or

diastems caused by solution due to acids in sea water and erosion by submarine currents may have

reduced the original thickness of some formations. Geologists appreciated these limitations and hoped

that a method would be discovered which would yield convincing evidence of the vast time recorded

in rocks. Unexpected help came from physicists studying the radioactive behavior of certain heavy

elements such as uranium, thorium, and actinium. These elements disintegrate with the evolution of

heat and give off particles at a constant rate that is not affected by high temperatures and great

pressures. Helium gas is liberated, radium is one of the intermediate products, and the stable end

product is lead with an atomic weight different from ordinary lead. Eight stages have been established

in the radium disintegration series, in which elements of lower atomic weights are formed at a rate

which has been carefully measured. Thus, uranium with an atomic weight of 238 is progressively

changed by the loss of positively charged helium atoms each having an atomic weight of 4 until there

is formed a stable product, uranium lead with an atomic weight of 206. Knowing the uranium-lead

ratio and the rate at which atomic disintegration proceeds, it is possible to determine the time when the

uranium mineral crystallized and the age of the rock containing it. By this method the oldest rock,

which is of Archeozoic age, is 1,850,000,000 years old, while those of the latest Cambrian are

450,000,000 years old. Allowing time for the deposition of the early Cambrian formations, the

beginning of the Paleozoic is estimated in round numbers at 500,000,000 years ago. This method dates

the oldest intrusive rock thus far found to contain radioactive minerals. But even older rocks occur on

the earth's surface, for they existed when these intrusions penetrated them. How much time should be

assigned to them, we have no accurate way of judging. Recently attention has centered upon the radio

activity of the isotopes of potassium, which disintegrate into calcium with an atomic weight of 40

instead of 40.08 of ordinary calcium. On this basis A. K. Brewer has calculated the age of the earth at

not more than 2,500,000,000 years, but there is some question that this method has the same order of

accuracy as the uranium-lead method. Geologists are satisfied with the time values now allotted by

physicists for the long intervals of mountain-making, erosion, and deposition by which the earth

gradually reached its present condition.

DIVISIONS OF GEOLOGICAL TIME

The rocks of the accessible part of the earth are divided into five major divisions or eras, which are in

the order of decreasing age, Archeozoic, Proterozoic, Paleozoic, Mesozoic, and Cenozoic.

Superposition is the criterion of age. Each rock is considered younger than the one on which it rests,

provided there is no structural evidence to the contrary, such as overturning or thrust faulting. As one

looks at a tall building there is no doubt in the mind of the observer that the top story was erected after

the one on which it rests and is younger than it in order of time. So it is in stratigraphy in which strata

are arranged in an orderly sequence based upon their relative positions. Certainly the igneous and

metamorphic rocks at the bottom of the Grand Canyon are the oldest rocks exposed along the

Colorado River in Arizona and each successively higher formation is relatively younger than the one

beneath it. The rocks of the Mississippi Valley are inclined at various angles so that successively

younger rocks overlap from Minnesota to the Gulf of Mexico. Strata are arranged in recognizable

groups by geologists utilizing a principle announced by William Smith in 1799. While surveying in

England Smith discovered that fossil shells of one geological formation were different from those

above and below. Once the vertical range and sequence of fossils are established the relative position

of each formation can be determined by its fossil content. By examining the succession of rocks in

various parts of the world it was found that the restriction of certain life forms to definite intervals of

deposition was world wide and occurred always in the same order. Apparently certain organisms lived

in the ocean or on the land for a time, then became extinct and were succeeded by new forms that were

17

Reading skills for academic study

usually higher in their development than the ones whose places they inherited. Thus, the name

assigned to each era implies the stage of development of life on the earth during the interval in which

the rocks accumulated. The eras are subdivided into periods, which are grouped together in to indicate

the highest forms of life during that interval. As the rocks of increasingly younger periods are

examined higher types of life appear in the proper order, invertebrates, fish, amphibians, reptiles,

mammals, man. From this it is evident that certain fossil forms limited to a definite vertical range may

be used as index fossils of that division of geological time. Also, in this table are given for each era

estimates of the beginning, duration, and thickness of sediments, based largely upon a report of a

Committee of the National Research Council on the Age of the Earth. At the close of and within each

era widespread mountain-making disturbances or revolutions took place, which changed the

distribution of land and sea and affected directly or indirectly the life of the sea and the land. The close

of the Paleozoic era brought with it the rise of the Appalachian Mountains. It has been estimated that

only 3 per cent of the Paleozoic forms of life survived and lived on into the Mesozoic era. The birth of

the Rocky Mountains at the close of the Mesozoic was accompanied by widespread destruction of

reptilian life. Faunal successions responded noticeably to crustal disturbances.

UNCONFORMITIES. In subdividing rocks geologists have been guided by the periods of erosion

resulting from extensive mountain construction. Uplift of the continents causes the shallow seas to

withdraw from land thereby deepening the ocean and allowing erosion to start on the evacuated land

areas. Since all the oceans are connected, sea level throughout the world was affected in many

instances, leaving a record of crustal movements in the depositional history of each of the continents.

At many places the rocks of one era are separated from those of another by unconformities or erosion

intervals, in which miles of rocks were eroded from the crests of folds before sedimentation was

resumed on the truncated edges of the mountain structure. There are four stages in the development of

an angular unconformity, so named because there is an angular difference between the bedding of the

lower series and that of the overlying series. If the series above and below an unconformity consist of

marine formations, four movements of the area relative to sea level took place. In stage 1 the

sandstones and shales comprise a conformable marine series, which was laid down by continuous

deposition with the bedding of one formation conforming to the next. We have seen that the deposition

of 24,000 feet of sediment requires repeated sinking of the area below sea level. In stage 2 the region

was folded and elevated above sea level, so that erosion could take place. Since erosion starts as soon

as the land develops an effective slope for corrosion, there is no proof that this structure ever stood

24,000 feet high. But, the evidence is clear that 24,000 feet were eroded to produce the flat surface,

shown in stage 3. In order that the over lying marine series could be deposited the area had to be again

submerged below sea level. Since the region now stands above sea level, a fourth movement is

necessary. In some cases crustal movement does not tilt or fold the beds, but merely elevates

horizontal strata so that erosion removes material and leaves an irregular surface on which

sedimentation may be resumed with the deposition of an overlying formation parallel to the first. An

erosion interval between parallel formations is a disconformity. But not all unconformities and

disconformities are confined to the close of eras. Local deformation and uplift caused erosion between

formations within the same era and within the same period. In the Grand Canyon region Devonian

rocks rest on the eroded surface of Cambrian formations. At other North American and European

localities Ordovician and Silurian rocks occupy this interval, so that the disconformity within the

Paleozoic era at this locality represents two whole periods. It is only by carefully tracing the sequence

of rocks of one region into another that the immensity of geological time can be appreciated from

stratigraphy. -

Exercise 4

In Sociolinguistics by R A Hudson, many new words are clearly explained in the text.

Can you work out the meanings of the words in bold.

Most of the people are indigenous Indians, divided into over twenty tribes, which are in turn grouped

into five 'phratries' (groups of related tribes). There are two crucial facts to be remembered about this

18

Reading skills for academic study

community. First, each tribe speaks a different language - sufficiently different to be mutually

incomprehensible and, in some cases, genetically unrelated (i.e. not descended from a common 'parent'

language). Indeed, the only criterion by which tribes can be distinguished from each other is by their

language. The second fact is that the five phratries (and thus all twenty-odd tribes) are exogamous (i.e.

a man must not marry a woman from the same phratry or tribe). Putting these two facts together, it is

easy to see the main linguistic consequence: a man's wife must speak a different language from him.

We now add a third fact: marriage is patrilocal (the husband and wife live where the husband was

brought up), and there is a rule that the wife should not only live where the husband was brought up,

but should also use his language in speaking to their children (a custom that might be called

'patrilingual marriage'). The linguistic consequence of this rule is that a child's mother does not teach

her own language to the child, but rather a language which she speaks only as a foreigner...

Word

Meaning

phratry

genetically unrelated

exogamous

patrilocal

patrilingual marriage

Gap-fill exercise

Choose the correct word for each gap. Use the context to help you decide on the correct

answer. Press "Check" to check your answers.

The first adding machine, a precursor of the digital computer, was

French philosopher Blaise Pascal. This

tooth representing a digit from 0 to

be

in 1642 by the

employed a series of ten-toothed wheels, each

. The wheels were connected so that numbers could

to each other by advancing the wheels by a correct number of teeth. In the 1670s the

German philosopher and

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz improved on this machine by

devising

one

that

could

also

.

The French inventor Joseph Marie Jacquard, in designing an automatic loom, used thin, perforated

boards to control the weaving of complicated designs. During the 1880s the American

statistician Herman Hollerith

the idea of using perforated cards, similar to Jacquard's

boards, for processing data. Employing a system that

contacts, he was able to

punched cards over electrical

statistical information for the 1890 United States census.

Civilization and History

Read the text on the right and choose the correct answer for each question.

19

Reading skills for academic study

1 This essay can be divided into two main parts, although it has three

paragraphs. Where does the second part begin?

At the beginning of the second paragraph.

At the beginning of the third paragraph.

2 Which of the followings sentences gives the best summary of the

first part?

Some of the people who helped civilization forward are not mentioned

at all in history. books.

Conquerors and generals have been our most famous men, but they did

not help. civilisation forward.

It is true that people today do not fight or kill each other in the streets.

3 Which of the following sentences best summarizes the second part

of the essay?

In order to understand the long periods of history, we have to scale

them down to shorter periods.

The past of man has been on the whole a pretty beastly business.

Mankind is only at the beginning of civilized life; so we must not

expect a great deal of civilization at this stage.

4 In the first sentence the author says that

most history books were written by conquerors, generals and soldiers.

no one who really helped civilisation forward is mentioned in any

history book.

history books tell us far more about conquerors and soldiers than about

those who helped civilisation forward.

conquerors, generals and soldiers should not be mentioned in history

books.