constitutional development in nigeria

advertisement

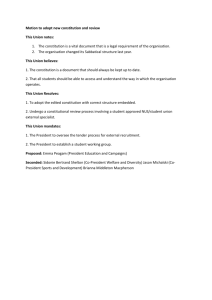

DYNAMICS OF CONSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENT IN NIGERIA, 1914-1999 Indian Journal of Politics(XL No 2&) April -Sept 2006) S.O. Aghalino Abstract: This article examines the intractable problem of constitutional engineering in Nigeria. It is asserted that the drafting of constitutions is a recurring decimal in Nigeria’s chequered political history. Right from the colonial period, Nigerians were barely involved in the art of constitution making while the British colonial overlords employed constitution making to consolidate their imperial strategies. Post colonial Nigerian leaders have utilized constitution drafting to ensure regime longevity. The current 1999 constitution is a product of haste because the receding military junta was in a hurry to leave the political turf. Consequently, the 1999 constitution has all the trappings of military centralization of power resulting in de-federalization of Nigeria and the consequent clamour and agitation for the amendment of the constitution. Introduction: The drafting of constitutions has been a recurring decimal in the political history of Nigeria. Right from the colonial period, Nigeria has witnessed incessant clamour for one form of constitution or the other. The series of constitutions that were put in place during the colonial period were geared towards consolidating British imperial strategies. ____________________________ 1 Senior Lecturer, department of History, University of Ilorin, Nigeria Dynamics of Constitutional Development in Nigeria, 1914-1999 2 The point to note about colonial constitutions is that, the Nigerian people were barely involved in the drafting process. When Nigeria was eventually de-colonised, post-colonial constitutions reflected the idiosyncrasies and worldview prospective leaders, with little consideration for the interests of the citizenry. This is particularly so because post-colonial Nigerian politics has been dominated by one ruling military junta or the other. Indeed, constitution drafting initiatives embarked upon by successive military regimes were merely cosmetic and plastic. At best, they were time saving devices to ensure the longevity of their regimes. In this paper, an attempt has been made to review, albeit briefly, constitutional development in Nigeria. While it could be taken for granted that colonial and military constitutions have generated due attention, it appears that the 1999 Constitution which is presently in operation has not received due attention from scholars. In this light, the bulk of our analysis will tilt towards the 1999 Constitution while assessing how earlier efforts have coloured it. Attributes of a constitution: The constitution of a State is that collection of rules and principles according to which a state is governed. In other words, the Constitution refers to the framework or the composition of a government, the structure with regards to its organs, how power is allocated and the process by which power is exercised. 1 The criterion which served as the basis for assigning political powers reflects the ethos of a given society. Nevertheless, it is conventional for the present day constitutions to reflect the composition of government and the relationships among these institutions. 3 Second, a constitution should provide for the distribution of governmental power over the nation’s territory. Third, and more importantly, a constitution should provide a compendium of fundamental rights and duties of citizens including their rights to participate in the institutions of government.2 Among the aforementioned attributes, the fundamental and inseparable segment of the constitution is its origin from the organic will of the people who it governs. This is referred to as in the autonomy of constitution, implying that the people have been part of the deliberation, formulation and adoption of the constitution, taking the heterogeneous nature of such a country as reflected in her multi-ethnic, multi-linger and multi-religious nature.3 since the constitution must be, logically, the original act of the people directed resulting from the exercise of the inherent power, it becomes a binding instrument by which the sovereignty of the people is measured. Thus, the phrase ‘we the people….hereby resolve to make for ourselves the following constitution’, should not be dismissed as a mere preliminary formalism because it suggests that the document is a replica of the compendium of the people’s view and the objectives of their association. The question that naturally arises is whether successive Nigerian constitutions contain the above-identified salient pre-requisites for a good and durable constitution. A close examination of the litany of constitutions in Nigeria should assist us to drive home the point. Constitutional development in Nigeria: A synopsis: It is on record that until now, eight constitutions have been operated in Nigeria. It began with the sir Frederick Lugard’s Amalgamation Report of the 1914. 4 Thereafter, there were the sir Clifford Constitution (1922); Sir Arthur Richards Constitution (19465); Sir John Macpherson Constitution (1951), Oliver Littleton’s Constitution (1954), the Independence Constitution (1960); the Republican Constitution (1963) and the 1979 Constitution (1979).4 There was another draft Constitution in 1989 prepared during the regime of former President Ibrahim Babangida. This was never tried until general Sanni Abacha’s administration brought about the 1994/95 constitutional Conference, which laid the foundations for the 1999 Constitution. The Clifford constitution, which was introduced by sir Hugh Clifford in 1922, replaced both the Legislative council of 1862 which was subsequently enlarge in 1914, and the Nigerian council of 1914. Under the Constitution, a Legislative Council was for the first time established for the whole of Nigeria, which was styled as, ‘The Legislative Council of Nigeria.’5 In spite of the embracive colouration of the Council, its jurisdiction was confined to the southern Provinces, including the colony of Lagos, whose Legislative council was subsequently abolished. The Legislative Council did not legislate for the Northern Provinces but its sanction, signified by a Resolution was necessary for all its expenditure out o 5the revenues of Nigeria in respect of those Provinces.6 The point to note is that the Nigerian Council was not created for any altruistic motive, But rather to ‘enable the British officials obtain, in the central exercise of their power, as much local advice and opinions as could be evoked.’ One feature of Clifford’s Constitution was that only Africans with minimum gross income of $100 a year were eligible to vote and be voted for.7 5 This might have been a strategy to divide and rule – a fallout off the so-called ‘Indirect rule Principle’ that was in operation in colonial Nigeria. Though, this charge cannot be easily denied, there is no written evidence that it was in operation. The elective principle in the Constitution simulated political activities in Lagos as in other parts of Nigeria and by extension created the leeway for the formulation of political parties. Besides, the wide powers conferred on the governor created a forum for unrestrained use of absolute power and this was naturally unacceptable to Nigerian nationalists. The disaffection caused by Clifford’s constitution invariably created the need for another constitution. Thus, when Sir Richards became the governor of the colony of Nigeria, he initiated moves to draft a new constitution. In March 1945, through a Sessional Paper Number 4, the Chief Secretary to the government, sir general whitely, initiated a motion in the Legislative Council which was passed unanimously in the House. This motion for a new constitution gave birth to the Richards Constitution. In this constitution there was one Legislature for the whole of Nigeria. It also made provisions for three delineated provinces, viz – North, West and East. There was an overwhelming African majority, but were not to be elected in the provinces and the Central Legislative House.8 The constitution also created three regional Assemblies. The monetary requirement noticeable in Clifford’s Constitution was reduced in order not to disenfranchise eligible voters and contestants for political offices. The salient feature of the Richards Constitution is the emphasis on regionalism with its attendant negative consequences. 6 In spite of the fact that some concessions were granted to Nigerian nationalists in the Richards constitution, it was regarded as a divisible document. In fact, Nigerian nationalists opposed Richards Constitution on two major pedestals. The first was the manner and procedure by which the constitution was introduced. Second, and most importantly, were its inherent weaknesses. Just like Clifford’s Constitution, Nigerians were hardly given the opportunity to shape their future. The constitution did not make provisions for the training of Nigerians in their gradual march towards self-rule.9 Richard’s constitution could not run its full course of nine years due to the vociferous opposition to its configurations. In order, therefore, to “rectify” the perceived deficiencies of Richard’s Constitution, when Sir Macpherson became the Governor of Nigeria in 1948, he decided to fashion out a new Constitution. After much deliberations and debates of the draft constitution Macpherson Constitution (1951) sought to impose a colonial hybrid arrangement, which had the characteristics of both Federal and unitary legal frameworks.10 Nevertheless, it represented a major advance from the pre-existing constitutional provisions because it introduced majorities in the Central Legislature and the Regional Houses of Assembly. Among other provisions of the constitution were a Central Legislative Council, Central executive Council, Regional Executive Councils, Regional Legislature and the establishment of the Public Service Commission. One shortcoming of the Constitution which was conspicuously highlighted was the establishment of a Regional Legislature. This invariably led to the emergence of ethnic-based parties such as the National Council of Nigerians and the Cameroons, (NCNC) Action Group,(AG) and the Northern Peoples congress, (NPC). The acrimonious way these parties contested the elections has been duly documented. 7 Despite the fact the Macpherson Constitution represented a major constitutional advance, yet it was unsatisfactory to Nigerian nationalists who vigorously campaigned for its sack. Consequently, the Macpherson Constitution was set aside and replaced by the Littleton Constitution, which laid the foundations for a classical Federation for Nigeria. The component units of Nigeria were “separate yet united” in their sub-economies, civil service, legislature and public services.11 The constitutional evolution of Nigeria which started in concrete terms with the Clifford’s constitution of 1922, climaxed with the enactment of the1960 Independence constitution. The Constitution, as expected, was fashioned after the British West Minster model. Amongst its provisions was the presence of the office of governor-General who was the non-political Head of State, while the Prime Minister was the Head of government. Even when Nigeria became a republic in 1963, the Republican constitution did not change this position but merely removed the constitutional umbilical cord binding Nigeria to Britain.12 Within six years of independence, the constitution had failed, basically due to the cracks that had started appearing within its first two years. One of the factors that led to the collapse of the first republic was the nature of political authority within the State. The President, who was constitutionally, the chief executive usually, exercised his powers on the advice of the Prime Minister and his Cabinet Members. The West Minster model could not fit into African society where “the leader wants to assert his authorities without restraint.”13 Expectedly, there were ‘clashes between the President and the Prime Minister, the climax of which was the federal elections crisis of 1964.14 8 The consequent collapse of the First Republic in January 1966 and the assumption of position of governance by the Military dealt a fundamental blow on constitutional development in Nigeria. It would appear that the discovery of the apparent con traditions in the parliamentary system of government made the drafters of the 1979 Constitution to jettison the dual system of leadership for the executive presidential system. The Constitution Drafting committee admirably rationalized the choice of the presidential system when it claimed that the choice was based on the need for:Effective leadership that expresses on aspiration for national unity without at the same time building a leviathan whose powers may be difficult to curb.15 The process and ways of curbing the powers of the President were enshrined in the Constitution and were also rooted in the principle of separation of powers. One fundamental innovation in the 1979 Constitution was the primacy given to federal character principle aimed at national integration and equitable representation of all the ethnic groups.16 The inadequacy of the federal character principle has received due attention from scholars. A related stabilizing device in the 19790Constitution was the prescription that political parties should not be ethnically based. Ethnic politics was an observable feature of the First Republic. It is difficult to accept the 1979 Constitution as a document which emanated from the people. This is particularly so because the Constitution was not adopted by the people through a referendum, although there was a Constituent Assembly established through a military decree in 1977 with 230 members. 9 It is relevant to add that of this number, 20 were appointed by the government. Other members were elected not direly by the people rather they were elected by the local councils acting as electoral colleges.17 Clearly, a Constituent Assembly Elected this way cannot claim to have the mandate of the people to adopt a Constitution on their behalf. An attempt was also made by the General Ibrahim Babangida administration to draft a constitution for the country. Indeed, a constitution was drafted for Nigeria. The 19089 Constitution was promulgated through Decree Number 12 of 1989.18 As things were, a Constitution review process was embedded on the transition programme of the administration. A close scrutiny, of the modalities for drafting the 1989 Constitution would suggest that there was adequate consultation and had some semblance of popular participation. In reality however, the outcome of the process turned out to be highly influenced and manipulated. At the end, one critic stressed, “the outcome was more of political engineering than of popular consultation and participation.”19 What is important, however, is the fact that the provisions of the 1989 Constitution did not depart markedly from the 1979 Constitution.20 The 1999 Constitution: An Appraisal: The Constitutional conference, which produced the 1999 Constitution, was inaugurated in 1994 in the wake of the turmoil that greeted the annulment of the June 12, 1993 Presidential election. Some members of the conference were “elected” ⅓of he members of the conference. Those appointed were pliant individuals who openly canvassed the position of the regime ofn the floor of the Conference. 10 As was expected, the Abacha regime used its effective grip on the technical and executive committees of the Constitutional Conference to manipulate the decisions arrived at on the floor of the Conference. Nevertheless, the Body identified and somehow discussed Nigeria’s problems for well over a year before it wound up. No doubt, the Conference had an image problem, as participants were highly discredited. Suffices to say however that, in spite of the tensed-up political atmosphere they worked, the body brought some ideas that could lead to solving nation’s myriad problems. Immediately after the conference submitted its reports, the Abacha regime appointed another Constitution review Committee (CRC) consisting of about 40 persons to “rework” the report and evidently make if in tune with the self-succession agenda of his regime. When the CRC finished its task in 1997, its report was further subjected to scrutiny by a group of close advisers to Generals Abacha. The point to note is that the recourse to the drafting of constitution by the Abacha regime, apart from securing his self-succession agenda, was merely diversionary in order, for the regime, to consolidate its hold on the nation. Expectedly, the regime reasoned just like Babangida initiative that, once the people were pre-occupied with the “why and how” of constitution making, their attention would be diverted from the monstrous policies of the regime. But the Nigerian people did not fall for this, as they were hell-bent on subverting the Abacha regime. In any case, General Abacha did not live long enough to actualize his self-succession agenda s he died mysteriously in June 1998. 11 With his death, General Abdulsalam Abubakar’s regime re-invigorated the hope of Nigerians when it became clear at the beginning that the new regime was willing to be difficult from the high handed regime of General Abacha. This ray of optimism was again buoyed up with the dismantling of some of the transition structures of Abacha’s administration. The people’s positive euphoria was dimmed when Generals Abubakar announced that his administration was willing to review Abacha’s 1995 draft constitution with a view to its possible adoption.21 To most Nigerians, this was rather an unpopular measure. Critics insisted that everything associated with generals Abacha should be discountenanced including the constitution. The Abubakar administration was not receptive to this radical posture. Instead, it raised a committee to organize a debate on the draft. The committee was named the Constitution Debate Co-coordinating Committee. Shades of opinion were harvested by the committee, which later submitted its report to the government in the end of December 1998. An overriding opinion of the “debaters” was put together. The over-riding feeling was a preference for the 1979 Constitution. Some amendments and reviews were recommended. The 1999 Draft Constitution was signed into Law on May 5, 1999 after an agonizing wait. It is obvious that the 1999 constitution being practiced today was hurriedly put together. Besides, it was exclusive and devoid of consultation and popular participation. However, it may be said that Abdulsalam’s regime would no really harvest different shades of opinion before the 1999 Constitution was drafted is understandable. 12 The regime was in a hurry to conduct elections and relinquish power to a democratically elected civilian administration because popular opinion was against continuous stay of the military in politics. Since the 1999 constitution came into force on May 29, 1999, it has been variously dismissed as a “false” document and a mere Tokunbo (fairly used). The preamble, which states among other things “we the people of the federal Republic of Nigeria do hereby make, enact and give to ourselves the following constitution”, amounts to a false claim.22 It would appear that this criticism is predicated on the fact that the people of Nigeria were barely consulted before the 1999 Constitution was enacted. Nonetheless, some salient provisions in the constitution deserve a close study. A cursory look at the second Schedule of the Constitution which deals with the legislative powers of the National Assembly under the executive lists reveals that all the important sectors of the society are listed here. The import of this is that, the ability of the State assemblies to legislate on these matters is restricted. And to this extent, the pseudo-sovereignty of the States in the Federation is greatly checkmated in such a way that the federal arrangement appear in reality to be a unitary one.23 The erosion of the powers of the States is more pronounced when Part II of the Second Schedule of the Constitution, which deals with the concurrent powers of the federal government and the federating states, is examined.24 section 4 (5) in clear language, gives the National Assembly express power where there is a conflict between the laws enacted by the States Assembly and the National assembly. This gives the impression that the States are mere appendages of the federal government when in reality they are part of a whole.25 13 With regard to public revenue allocation, as spelt out under Section 162 of the Constitution, the revenue allocation formula titled heavily in favour of the federal Government. Of particular interest is in the realm of derivation. The Constitution is succinct when it states that “The principle of derivation shall not be less than 13 per cent of the revenue accruing to the federal Account directly from natural sources.”26 The handling down of the percentage to be paid on derivation negates the principle of true federalism.27 It is not surprising therefore that oil mineral producing states have opposed the 13 percent derivation and instead are clamouring for total control of their resources while agreeing to pay taxes to the Federal Government.28 A corollary to this is that Item 34 on the executive Legislative List empowers the central government to legislate on national minimum wage There is no doubt that this is in prejudice to the disparity in conditions of service, revenue, derivation and resources of each State. Recent events in the country clearly demonstrate the absurdity of this Section of the constitution. Currently, there are spates of strikes and lock-outs in virtually all the States in the country in view of the demand for a new minimum wage which the federal government pegged at seven thousand and five hundred Naira (about $54) for Federal workers and five thousand and five hundred Naira for State workers (about $39). Naturally, States should determine how much they could pay to their workers based on their available resources. The Federal Government has no business fixing of minimum wages for States. This perhaps haves demonstrated in bold relief, some of the contradictions in the 1999 Constitution. 14 One area in the Constitution, which has attracted so much controversy is Section k275, which provides that “There shall be, for any State that requires it, a Sharia Court of Appeal.” Section 277 provides that the ‘Sharia court of appeals of a state shall in addition to such other jurisdiction as may be conferred upon it by the law of the state, exercise such appellate and supervisory jurisdiction in civil proceedings involving the questions of Islamic Personal Law, which the court is competent to decide’… The Constitution no doubt recognizes the Sharia to the extent that Section 6(3), (5) recognizes a Sharia court of appeal as a court of superior record in Nigeria, but the constitution did not elevate Islam to a State religion. Indeed, Section 10 of the constitution of the federal Republic of Nigeria 1999 prohibits State religion.29 Thus, the foregoing provisions makes the official launching of the adoption of the Sharia in Zamfara and Kano States to be in direct conflict with the spirit and letter of the constitution of the Federal republic of Nigeria, 1999. It would appear that the authorities off the concerned States might have relied on Section 4 (7) of the 1999 Constitution, which states: ‘The House of Assembly of a State shall have power to make laws for the peace, order and good government of the State or any part thereof…’ Whatever be the provision of Section 4(7), it is clear that sub-section 4(7) (e) stipulates that the State Houses of assembly may make laws but must not contravene the provisions of the 1999 constitution. It is noteworthy that Sharia had been operational in some parts of Northern Nigeria even during the colonial period.30 15 It was then known as Alkali courts, now area courts. Under this system the Islamic law was employed only in civil and personal matters. With the adoption off the Sharia, all Muslims in the said states have to abide by the Sharia provisions in both civil and personal matters as well as criminal matters. The adoption of the Sharia has all the trappings of infringing on individual rights as provided for under Chapter IV of the 1999 Constitution. Under Section 130 of the 1999 Constitution, the President is described as the “Head of State, the chief executive of the federation and commander-in-Chief of the Armed forces.” In addition to the monstrous and alarming executive powers bestowed on the President; the President is empowered with legislative’ judicial powers to alter, amend, repeal, or modify any “existing” law so as to bring the law into conformity with the provisions of the constitution. Granted that a level-headed President would not deliberately abuse these enormous powers but there is no guarantee that a power-drunk President who is conscious of his powers would not abuse them and virtually declare a reign of terror on the citizenry by displaying dictatorial tendencies. Falana has shown that “it can be argued that what the 1999 Constitution had done is to confer all the dictatorial powers that hitherto were exercised by the former military Heads of state on the elected President of the Federal republic of Nigeria.”31 In a way this could be excused based on the background of the initiators of the constitution. The point was made earlier that the 1999 Constitution is a product of a highly exclusive, hurried and closed process. The present clamour for its disuse and/or review is therefore not unexpected. 16 The Constitution is widely rejected because it was imposed and it is entirely undemocratic as such it cannot serve as the foundation for a new Nigeria. There kis a concern and demand for a more open, legitimate and popular process of re3viewing the Constitution. This is particularly so when it is realized that the people’s aspirations have not been met by the 1999 Constitution. Popular participation in constitution making is essential because it confers legitimacy on it and by extension, makes it popular, acceptable and sovereign. The 1999 Constitution is merely an embellishment of a unitary constitution. It is clear that all the trappings of federalism have been eroded particularly in the realm of the control of resources and separation of powers within the various tiers of government. The Obasanjo regime seems to have acknowledged the deficiencies in the 1999 Constitution. The Obasanjo regime has responded positively to demands of Nigerians for the need to review the Constitution, hence, he set up the Yusuf Mamman – led Constitution Review Committee. The National Assembly appears to be working towards this direction with the setting up of its own Committee to review the constitution. Just like earlier attempts at constitution making, the present review process has been elitist rather than popular and much more exclusive rather than inclusive. The Yusuf Mamman Committee appears to be too elitist and technical to the extent that the committees sits in Abuja, the federal Capital and calls on Nigerian people to “submit memoranda in ten (10) copies typed in double spacing and submitted personally or by speed post or e-mail.”32 The point must be made that in this kind of elitist and exclusive arrangement, the voice of the “ordinary” Nigerian would not be heard. At the end of the exercise, the committee would submit a report that reflects the class and aspirations of the elites rather than a popular and a people-driven report. 17 Consequently, such thorny issues like Niger Delta question, the issue of Sharia, resource controls and the nationality debate would be treated as non-issues and the vicious cycle of constitution making would continue. Summary and Conclusion: The point has been made that right from the colonial period, Nigeria has had a plethora of constitutions. Starting from the 1914 initiative of Lord Lugard to the Independence constitution, the people of Nigeria were hardly involved in the drafting of their constitutions. We opined that the colonial state used constitution drafting to consolidate imperial strategies. The post-colonial period does not look promising. Post-colonial Nigeria until recently was dominated by the military who in a bid to earn legitimacy had drafted one form of constitution or the other. The current 1999 constitution is characterized by a number of deficiencies that have inevitably led to a clamour for its disuse. For one, it has all the trappings of a unitary constitution. The concept of federalism as embedded in the constitution is only a paid lip service. Nevertheless, the document may not be perfect, but it signals a starting point. In due course, it would be amended to reflect the views of Nigerians. In this process, it would fulfill one of the attributes of a constitution, which is that it should reflect the ethos of the people. 18 References: 1. Encyclopedia of Social Sciences, Vol. 3, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London, 1985, (Also see, Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative. “Consultation on Participation in constitution Making recommendation to CHOGM”, Holiday Inn, Burgerspark, Pretoria, 16-17 August, 1999. 2. B.O. Nwabueze, Ideas and Facts in Constitution Making. Spectrum Books, Ibadan, 1993, p.1. 3. Enugu, Friends of the Environment and Minorities, 1999. 4. The Guardian, Lagos, Nigeria, May 9, 1999. 5. B.O. Nwabueze, The Presidential constitution of Nigeria, C. Hurst & Co., London, 1982. 6. G.O. Olusanya, “Constitutional development in Nigeria, 1861-1960”, in O. Ikime (ed.), Groundwork of Nigerian History, Heinemann, Ibadan, 1980, p. 518. 7. N. Nwosu et.al., Introduction to Constitutional development in Nigeria, Sunad, Ibadan, k1998. 8. G.O. Olusanya, Op. Cit., p. 520. 9. K. Eso, “Opening address”, in Frederick Ebert, Constitution and Federalism, Frederick Ebert, Lagos, 1976. 19 10. Chief Obafemi Awolowo asserted that the Constitution failed to satisfy the three criteria by which federalism and Unitarianism should be judged and concluded that the Constitution was therefore “a wretched compromise between federalism and Unitarianism.” For details, see Awolowo, Awo: An Autobiography of Chief Obafemi Awolowo, Oxford University Press, k1960, p. 179. 11. The Guardian, Lagos, June 16, 1997. 12. M.O. Adeniran, “Separation of Powers in the 1999 Constitution: a Myth or Reality?”, paper presented at the 2000 Biennial Law Week of the Ilorin chapter of The Nigerian Bar association held on 18-20, April 2000. 13. Constitution Drafting Committee report, Vol. I, Federal Ministry of Information, Lagos, 1976. 14. A.A. Madiebo, The Nigerian revolution and the Biafran War, Enugu, Fourth Dimension, 19870, pp. 1-14. 15. CDC. Vol. II XXXI, k1978. 16. See Section 14 (3) of the 1979 Constitution. 17. R.T. Suberu, “Background Principles of Nigeria’s Presidential System”, in V.I. Ayeni and K. Soremeku (eds.),Nigeria’s Second Republic, Daily times, Lagos, 1988. 18. N. Nwosu, Op. Cit. 19. The Post Express, Lagos, September 6, 2000. 20 20. M. Abubakar, “The History of constitution Making in Nigeria (1922-1999)”, in CDHR, Path to People’s constitution, CDHR, Lagos, 2000. 21. The guardian, Lagos, May, 1999. 22. Community Rights Initiative, “We Cannot Go on Like this,” a position paper presented at the conference of the Peoples of the Niger delta and the 1999 constitution, port-Harcourt 2-04 November, 1999, p.1. 23. This kind of subtle device was also noticeable in the Macpherson constitution, which was desperately resisted by Nigerian nationalist. 24. See Part II, Schedule II of the 1999 Constitution. 25. Nigerian Institute of Human rights, “Federalism: The 1999 constitution and the People of the Niger Delta”, position paper presented at the conference of the people of the Niger Delta”, position paper presented at the conference of the people of the Niger delta and the 1999 constitution held in Port Harcourt, 2-4 November 1999, p. 3. 26. See Section 162 (2) of the 1999 Constitution. 27. B. Onimode, ”Fiscals Federation and revenue Matters in Nigerian Constitution”, Conference Paper. The centre for Democracy and Development (CDD), Nicon Hilton, Abuja, 1999. 28. The Guardian, Lagos, 16 July 2000; and The Comet, Lagos, 6 March 2000. 29. See Section 10 of the 1999 Constitution. 21 30. E.P.T. Crampton, Christianity in Northern Nigeria, Geoffrey Chapman, London, 1976. 31. F. Falana, “The Nigerian Federation, the 1999 Constitution and Sovereign National Conference”, in CDHR, Path to People’s Constitution, CDHR 2000, p.133. 32. J.O. Ihonybere, “Towards Participatory Mechanisms and Principles of constitution Making in Africa”, in CDHR, Path in People’s Constitution CDHR, Lagos, 2000.s