Imagine I have invented a device—the JulesVerne-o

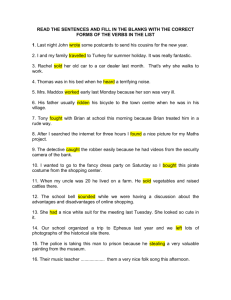

advertisement

From Why Privacy Matters Richard Warner The JulesVerne-O-Scope, Privacy, and the Internet Imagine Brian invents a device—the JulesVerne-O-Scope—which allows him to view a video-like display of any part of anyone’s past. When, in the spirit of scientific experiment, Brian asks his friend, Brianna, to consent to his viewing her past, she declines. She objects to losing control over what Brian knows about her. She objects, for example, to his learning what she is really willing to pay for the house she is offering to buy from him; and, she objects to his learning facts she would reveal only to more intimate friends—such as her feelings about her marriage. When she withholds consent, Brian promises not to use the device, but she does not trust him, and, over time, she begins to suspect he is viewing her past. She begins to wonder constantly whether and to what extent what Brian says and does in her regard is premised on knowledge he has obtained using the JulesVerne-O-Scope. She fears Brian’s new found power and resents his transgression of her boundaries of intimacy. The distrust, fear, and resentment destroy the friendship, and Brianna eventually refuses even to be in the same room with Brian. Compare their pre-Jules-Verne-O-Scope friendship. Both were limited in what they knew about each other, and, to a considerable extent, both knew those limits: they knew what they did and did not know about each other. Both knew that Brian did not know how much Brianna was willing to pay for the house, and that he did not know her unexpressed feelings about her marriage. Against this background of shared knowledge of knowledge limits, Brianna was confident that Brian did not have unwanted power over her in the house deal, and that Brian’s knowledge did not exceed Brianna’s degree of intimacy. Brianna interpreted Brian’s words and actions against this background, and, exceptional circumstances aside, did not worry that he knew personal facts she desired he did not know. In general, we conduct our relations with others against a background of shared knowledge of the limits of our knowledge of each other. A device like the JulesVerne-O-Scope would, if widely used, fundamentally alter this background by reducing the amount of information we knew others did not know about us. Two things would happen as a result. First, many people would be disadvantaged in ways they would not be if the device did not exist. Newspaper and magazines could—and no doubt some would—discover and publish the names of rape victims and thereby cause them great emotional distress. Employers would discover their potential or current employees’ political affiliations, sexual preferences, past crimes, and the like, and refuse to hire them or fire them as a result. Most will deplore the publication of the rape victims’ names; what an employer is entitled to know is, on the other hand, considerably more controversial. There would also be a second result, and this is the result I want to emphasize here. In doing so, I by no means intend to minimize the harms that the disclosure of personal information may cause; however, many have already emphasized this point. The second result would be a fundamental change—for better or worse—in our relations with each other. Those relations are premised in part on what we know others do not know about us. Change that background knowledge, and you alter the relationship. This is the point of the Brian/Brianna example. Suppose that Brian never does use the JulesVerne-O-Scope to view Brianna’s past; nonetheless, Brianna’s suspicion destroys her prior confidence that Brian did not know certain things about her and replaces it with distrust, fear, and resentment. The effect need not be so corrosive, of course. Brianna might react by ceasing to care so much about what others think of her and, as a result, enjoy a new-found sense of peace. But the point still stands: change the background knowledge, and—for better or worse—you change our relations with each other. The JulesVerne-O-Scope does not exist. But computers, databases, and the Internet do. Advances in surveillance techniques allow us to collect, search, and analyze vast amounts of information, and the Internet worldwide distribution. Does the availability of this information amount to something akin to a JulesVerne-O-Scope? If so, what will the effect be on the background of knowledge against which we conduct our relationships with others? It helps here to borrow the game-theory concept of common knowledge. Something is common knowledge between you and me when (and only when) we know it; we know we know it; we know we know we know it; and so on. Suppose, for example, that you and I make eye contact; we see each other seeing each other and hence know that we are making eye-contact; know that we know; know that we know that we know, and so on. In general, shared culture, education, and experience create a great deal of common knowledge. It is common knowledge among most U. S. citizens that George Washington was the first president of the United States. It is common knowledge between you (as the reader of these words) and me (as their writer) that these are English words. It is possible to redescribe the Brian/Brianna example in terms of common knowledge. It is—absent the JulesVerne-O-Scope—it is common knowledge between Brian and Brianna that Brian knows neither the top price she is willing to pay, nor her feelings about her marriage. The Brian/Brianna example illustrates the general point that we conduct our relations with others against a background of shared knowledge of the limits of our knowledge of each other. Recast in terms of common knowledge this becomes: we conduct our relations with others against a background of common knowledge of the limits of our knowledge of each other. The advantage of the common knowledge redescription of these facts is that it provides a broader context in which to set the fact that our relations with others proceed against a background of shared knowledge of the limits of our knowledge of each other. Common knowledge plays a role in a wide range of activities; indeed, as Peter Vanderschraff and Giacomo Sillair emphasize, [c]ommon knowledge is a phenomenon which underwrites much of social life. In order to communicate or otherwise coordinate their behavior successfully, individuals typically require mutual or common understandings or background knowledge. . . . If a married couple are separated in a department store, they stand a good chance of finding one another because their common knowledge of each others' tastes and experiences leads them each to look for the other in a part of the store both know that both would tend to frequent. Since the spouses both love cappuccino, each expects the other to go to the coffee bar, and they find one another.1 Prior to the JulesVerne-O-Scope, Brian and Brianna coordinated also coordinated their actions in light of their common knowledge. The JulesVerne-O-Scope destroys the coordination by destroying the common knowledge. Lack of common knowledge often causes lack of coordination. Vanderschraff and Giacomo Sillair offer the example of “a pedestrian [who]causes a minor traffic jam by crossing against a red light . . . [She] explains her mistake as the result of her not noticing, and therefore not knowing, the status of the traffic signal that all the motorists knew. . . . [T]he pedestrian and the motorists miscoordinate as the result of a breakdown in common knowledge.” 2 One well-known point about common knowledge is particularly important here: namely, doubt can easily undermine common knowledge.3 This is what happens in the Brian/Brianna example. Brianna begins to wonder—with some justification, let us suppose—whether Brian is using the JulesVerne-O-Scope to view her past, and, as result, she is no longer sure that he does not know, for example, the highest price she is willing to pay and her feelings about her marriage. She does not know that he does know; she just doesn’t know that he does not. She is just in doubt. The doubt is enough, however, to undermine the prior common knowledge about the limits of what they knew about each other. This brings us back to computers, databases, and the Internet. The digital and Internet revolution make vast amounts of information about people readily available worldwide. One thing seems clear: a profound change—for the better or worse—is already underway. Consider Facebook. Eight out of ten college students belong to Facebook, and the site draws 250,000 new members a day. [M]ore than 60 percent of Facebook users posted their political views, relationship status, personal picture, interests and address. . . . People also post a whopping 14 million personal photos every single day, making Facebook the top photo website in the country. Then users diligently label one another in these pictures, enabling visitors to see Peter Vanderschraff and Giacomo Sillair, Common Knowledge, http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/common-knowledge. 2 Peter Vanderschraff and Giacomo Sillair, Common Knowledge, http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/common-knowledge. 1 Michael Chwe, Structure and Strategy in Collective Action, 105 AMERICAN JOURNAL OF SOCIOLOGY 128 (1999); Michael Chwe, Communication and Coordination in Social Netoworks, 67 REVIEW OF ECONOMIC STUDIES 1 (2000); MICHAEL CHWE, RATIONAL RITUAL (2001). 3 every photo anyone has ever posted of other people, regardless of their consent or knowledge. . . . Facebook's 58 million active members have posted more than 2.7 billion photos, with more than 2.2 billion digital labels of people in the pictures.4 The default setting (which most users leave unchanged) makes posted information available to any other member of the Facebook network. Social networking sites like Facebook show that people (at least the younger generations) willingly share personal information with strangers. The result is a profound change in the common knowledge background. Where strangers have ready access to your personal information, you do not know what they know about you. They may know all the posted details, or none of them. Is this change for the better or the worse? Ari Melber, About Facebook, THE NATION, http://www.thenation.com/doc/20080107/melber 4