malaysian journal of tropical geography vol. 16 dec. 1987

advertisement

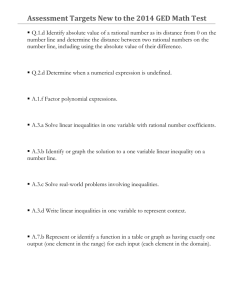

MALAYSIAN JOURNAL OF TROPICAL GEOGRAPHY VOL. 16 DEC. 1987 REGIONAL INEQUALITIES AND DEVELOPMENT IN PENINSULAR MALAYSIA 1970 — 1980 By Fauza Abdul Ghaffar Regional inequalities have existed throughout the development history of Peninsular Malaysia. The major characteristics of regional inequalities are unequal economic progress in the different states, differences in the per capita Gross Domestic Product between the states, differences in the structure of the state economy, variations in the rate of urbanization and, in terms of services, disparities in the standards of living arising from the uneven distribution of basic household amenities, particularly water supply, sewerage and electricity. Three major causes of regional inequalities have been identified. One of the causes is the impact of relief, climate and distribution of natural resources as well as the availability of infrastructure for the development of these resources and related activities. A second major cause may be attributed to colonial rule. British colonial rule had a significant impact on the social, economic and spatial structure of development which resulted in regional inequalities. British rule was centred in the towns, initially in the Straits Settlements (Melaka, Pulau Pinang, Dindings and Singapore) where the population was engaged in commercial pursuits and then in the west coast states especially Selangor, Perak and Negeri Sembilan where tin mining and rubber cultivation flourished. These capital-interest enterprises led to the control of the economy by the metropolitan power which in turn fostered a powerful economic link of the Peninsular economy to that of Britain, but at the expense of internal integration of the economy in the various states. Mass immigration of Chinese and Indians was encouraged by British economic policies. The policy of economic segregation led to the concentration of the major ethnic groups in specific economic sectors and separate areas in the Peninsula. The Chinese concentrated in industrial and commercial activities in the towns, the Indians in European-owned plantations, and the Malay farmers in the poorer, northern and eastern states. This pattern, although less predominant, persists until today. The third cause of regional inequalities may be due to insufficient attention of development planning on the special problems of a 'plural society' (Fisk 1962) and the spatial aspects of resource allocation. Development plans had focussed largely on sectoral allocation of resources and on the relatively well-developed areas of the country (Osborn 1974). Economic inequalities between states and ethnic groups led to serious social implications which constituted an indirect cause of the racial riots in May 1969. The riots forced the government to review the nature of economic inequalities which culminated in the introduction of the New Economic Policy embodied in the Second Malaysia Plan 1971-1975. The New Economic Policy recognized the deep-rooted problem of Malay economic inferiority and attempted to prescribe remedies. The Policy consists of two strategies, to be achieved over a period of 20 years, namely, to eradicate poverty by raising income levels and increasing employment opportunities for all regardless of race, and to accelerate the process of restructuring society so as to reduce and eventually eliminate the identification of race with economic function. The New Economic Policy thus marks the beginning of efforts in regional development through various policies and strategies. The period 1971-80 represented the first decade of the Outline Perspective Plan (OPP), 1971-1990, within which the objectives of the New Economic Policy were to be realized. It was also a period of favourable economic growth with an average per capita GDP of 7.8 per cent per annum (Fourth Malaysian Plan 1981-86). This paper examines the nature, scope and pattern of regional inequalities at the state level in the decade 19701980. The states provide an appropriate level of study as they coincide with the characteristics of Richardson's planning 24 FAUZA ABDUL GHAFFAR regions (Richardson 1974). The state is the areal unit of data compilation and for purposes of administration, planning and resource allocation. There are 12 states in Peninsular Malaysia which constitute distinct geographical and administrative entities (Fig. 1). Due to the problem of data availability, Selangor and Federal Territory (created in 1972) are considered as one state. Each state has its own hierarchy of villages and towns, rural and urban sectors and exhibits a diversity of income within its boundaries. Fig. 1 Peninsular Malaysia: States. An attempt is made to categorise the states in order to obtain a clear picture of the problem of inequality for future planning purposes. METHODOLOGY Due to the problem of availability, adequacy and .reliability of data (Ghaffar, 1981), the variables used in this study are necessarily limited in number. Nevertheless, 23 variables are selected to reflect the multi-dimensional nature of inequality (Table 1). These variables are divided into three groups, namely, five economic variables which show the structure, level of economic activities, output and income of the state, ten 1The social variables comprising health, education and amenities variables, and four demographic and urbanization variables which generally reflect the total population and its distribution. The above variables are subjected to analysis using the coefficient of spatial variation and Factor Analysis techniques. Coefficient of Spatial Variation The aim of using the coefficient of spatial variation is to assess the scope of relative variations between the states for the years 1970 and 1980. For this, the Coefficient of Spatial Variation (CSV)1 was computed for each of the variables on the basis of two measures, the mean and the standard deviation. The result of the above analysis would be sufficient to show the general trend of inequalities. formula for Coefficient of Spatial Variation is (Standard. Deviation) 100 Mean This ratio is similar to the one proposed by Thomson (1957). REGIONAL INEQUALITIES & DEVELOPMENT 25 However, although this seems valid in broad terms, the CSV may conceal important differences among the individual states. For example, it is not possible to have an idea of the relative position of individual states within a hierarchy of regional development. Thus a series of standard-scores i was computed for the variables to provide a means to rank and classify the states on a common scale and to ascertain whether or not certain states had become worse while others had improved their relative positions. THE NATURE AND SCOPE OF REGIONAL INEQUALITIES 1970-1980 To evaluate the nature regional inequalities between states in the period 1970-1980, the variations in the CSV between the variables and changes in the CSV of each variable in 1970 and 1980 are examined. The Situation in 1970 The 1970 data (Table 2) show that the variables present fairly high CSV indicating that inter regional inequalities were quite conspicuous. The economic indicators, especially variables 2 and 3, show high CSV indicating the differences in the structure of the economy of the states and the role of industry and manufacturing sectors in economic development. The CSV for variable 5, though considered low, still ranks higher than five other indicators. Indicators in the social sector, apart from variables 7 and 8, have uniformly lower CSV, reflecting less variations in the availability and distribution of such facilities from state to state. A notable feature is the very low CSV of the education indicators. This reflects the even distribution of education facilities and uniformity of education standard throughout the country, thanks to the efforts of the government in the provision of education throughout the country. An examination of the CSV of the variables shows that inter-regional inequalities were high in 1970, especially in the economic sector and the level of urbanization. Table 2, The Mean, Standard Deviation and Coefficient of Spatial Variation of Variables for 1970 26 FAUZA ABDUL GHAFFAR Variables 16, 17, 18 and 19 in the service and infrastructure sectors also exhibit high CSV. Variables 16 and 17 measure the variations in the extent of motorcar and motorcycle ownership between the states and variables 18 and 19 show variations in water and electricity consumption between the states. These variables indicate the high level of services available in the states of the west coast states compared with the east coast and northern part of the country. The demographic and urbanization indicators have high CSV, especially variable 22 (total urban population in each state). This reflects the concentration of the urban population in the towns of the west coast states. Similarly, variable 23 (percentage of population living in urban areas with a population of 10,000 or more) with CSV of 61.98, indicates marked variations in the distribution of population in urban and rural areas. It is noted that three-quarters of all the towns are found in the west coast states. The high CSV for variables 20 and 21 indicate the uneven distribution of population in the states. These variables help to identify areas of sparse population towards which population movements may be encouraged in regional development policies. The Situation in 1980 The 1980 data (Table 3) reveal a similar pattern of regional inequalities as 1970. Although many indicators point to a progress in the provision of socio-economic facilities, the level of inequalities still remains high. Variable 23 still leads the table, followed by three other variables in the demographic and urbanization sector indicating the persistence of the lop-sided distribution of urban population throughout the country. This is followed by indicators of the service sector which, despite decreasing in CSV, still remain high. Education facilities appear to be the least unequally distributed of all the services. The indicators in the economic sector reveal almost identical patterns as in 1970 with variables 2 and 3 showing the highest variations. Nevertheless, though the CSVs are high, the economic and social development levels have improved and inter-regional inequalities have consequently decreased in the economic sector. Table 3. The Mean, Standard Deviation and Coefficient of Spatial Variation of the Variables for 1980 REGIONAL INEQUALITIES & DEVELOPMENT Certain variables have recorded an increase in inequality among which variable 5 (per capita GDP ratio to average GDP in Malaysia), most of the demographic and urbanisation variables and, surprisingly, the education variables. The increase in inequality of education facilities might be due to the growing-number of children of school-going age in the population and the inability in the states to match the number of teachers with the growing enrolment in schools. CHANGING PATTERN OF INEQUALITIES 1970-1980 Changes in the CSVs of variables in 1970 and 1980 show that, despite remaining high, there has generally been a decrease in the variation of most indicators. Changes in the CSVs of the variables can be seen in Figure 2 and Table 4. In the economic sector, there is a relatively moderate decrease in variables 1, 2 and 3 but substantial in variable 4. More important is the increase in variation in the income indicator (variable 5) which clearly shows that although there is a slight restructuring of the economy in the states, income inequality has increased (Fig 2A). In the demographic and urbanization sectors, the variables yield extremely high CSVs. Except for variable 23, all the other variables register an increase in CSV reflecting greater uneven distribution of population and the level of urbanisation in the country (Fig. 2B). Most of the social and infrastructure variables (Fig. 2C) show a decrease in the CSV. However, the CSV of the service and infrastructure variables are high. In the health sector there is also a slight decrease in CSV, and although there is an increase in the CSV of the education sector it is still the most widespread service available. Fig. 2 Changes In the Economic, Demographic and Social Variables, 1970 — 1980. 28 FAUZA ABDUL GHAFFAR Table 4 shows several features in the relative variations of the variables. Firstly variables which record high CSVs may register a decrease in CSV as in variables 16, 17, 18 and 19 or an increase in CSV as in variables 20 to 23. On the other hand there was also a decrease in the CSV among social indicators with moderate CSVs. Do these features have any impact on the policy of regional development, more specifically have government efforts in regional development been concentrated in a limited area of socio-economic development ? The nature of regional inequalities is related to the multi-dimensional aspect of development. The decade of overall economic growth in the 1970s has indeed led to a decrease in economic inequalities. To have a clearer picture of the situation it would be appropriate to look at the performance of the individual states. RANKING AND CLASSIFICATION OF THE STATES The ranking and classification of individual states can show the relative position of each state in 1970 and 1980 and how each fared in socio-economic development during the decade. Following the work of Nacer (1979) two methods have been used, the first one consisted of a mere ordering of the states according to the individual variables and the summation of their ranks. The second and more common method applies basically the same principles as the first one but uses all the information available and thus allows for the cumulative effects of the previously standardized scores. Table 5 shows the rank of each of the states for both the years 1970 and 1980. Several important features are discernible. Selangor remains first on the rank for both years with scores far ahead of the others. Table 4. Changes in the Coefficient of Spatial Variation of Variables between 1970 and 1980 The second to sixth ranked states are formed by states in the west coast states from Pulau Pinang in the north to Johor in the south. The remaining states at the bottom of the ranks are those of the north and east coast states. Based on the ranking of the Z-scores, a classification of the states can be made. Generally the conventional eastwest dichotomy of development levels in Peninsular Malaysia is clearly revealed with the west coast states being more developed than the east coast states. The Developed States The 1970 data show that the developed states, ranked first to sixth, form a contiguous zone along the west coast of the Peninsula. Based on the socio-economic indicators used in this study, these states can be further divided into groups according to their relative rank scores. (i) Leading all other states by a wide margin is Selangor/Federal Territory. This state is well provided with social services and infrastructure and has a high level of urbanisation, especially the Kelang Valley where Kuala Lumpur is situated, and forms the most industrialised state in the country. Agriculture, on the other hand, plays a relatively minor role in the economic development of this state. (ii) The west coast state of Pulau Pinang in the north and Negeri Sembilan south of Selangor. Pulau Pinang in recent years has grown rapidly in industrial and port facilities. (iii) The states of Perak, Melaka and Johor. The Less Developed States The states which show low values in most of the variables constitute the less developed states. These states are found in the northern and eastern parts of Peninsular Malaysia where agricultural activities constitute the major economic activity and the population is predominantly rural and Malay. These states may be divided into two groups. (i) The states of Pahang and Trengganu which possess natural resources such as forests, agricultural land and petroleum. These states form the resource frontier region of the country with substantial development potentialities. Several urban centres may become potential growth centres. (ii) The states of Kedah, Perlis and Kelantan which form the bottom rank of the table are rice-growing areas. Besides relying heavily on traditional agriculture, these states are deficient in social and infrastructure facilities. In 1980, the developed and less-developed states remain identical but with Pahang joining the rank of the former. Selangor/Federal Territory still dominates, followed by Pulau Pinang, Negeri Sembilan, Melaka, Perak, Johor, Pahang, Kelantan, Kedah and Perlis. Pulau Pinang in particular has experienced rapid growth. Despite certain improvements, Kelantan, Kedah and Perlis remain the least developed of the states. Figure 3 reveals the increase or decrease in the absolute scores of each state and the gradient of inequality over the decade 1970-1980. THE-SENSITIVE INDICATORS' AND THEIR EVOLUTION Improvement in the level of development in the less developed states has not reduced the extent of regional inequalities. This is because the developed states have also undergone development. This section will identify certain sensitive indicators which are common to the less developed states and consequently to specify the sectors which need particular efforts in development planning. Several methods can be used to determine the most sensitive indicators in the less developed states. A method is used by Nacer (1979) where concentration is made on the grouping of the regions and look at the variables which record the lowest rank. This is then expressed as a percentage of the lowest theoretical mark. In this study however, the method employed is by examining the ranks of the Z-scores of each of the indicators in the four less developed states. The rank of each indicator is noted, from which indicators which forms the lowest rank in the 4 states are recorded. If an indicator is ranked 8th, 9th, 10th and llth in each of the states, then it is considered a sensitive indicator. Fig. 3 Gradient of Regional Inequalities, 1970— 1980. One important feature depicted in Figures 3 and 4 is that there is no state belonging to the class -5.00 to -9.99 in 1980. This is the second group of the less-developed states which in 1970 consisted of the states of Kedah and Perlis. In 1980, Kedah is placed in a class higher and Perlis slips into a class lower than the class - 5.00 to 9.99. The performance of the states based on the set of socio-economic indicators shows significant spatial inequalities in the level of development. Although there have been several shifts in the rank of some states in the 1970s, these occur within a given category of development status. Despite a decrease in variation in most of the indicators, regional inequalities are still consi derable in 1980. Several indicators in almost every sector are very useful in defining the less developed states. The 1970 Z-scores reveal that variables 2. 3 and 5 of the economic sectors, and variables 6, 7, 8, 9, 16. 17 and 23 of the social, infrastructure and urbanisation indicators are found to be sensitive. Variables relating to education are the least sensitive of all because of the fairly equal level of provision of educational facilities in all the states. In 1970, variable 8 (the number of person per registered dentist) is found to be the most sensitive indicator in the less developed states. The 1980 Z-scores reveal almost similar numbers and type of sensitive indicators. Other than variable 8. which shows an improvement, the income and urbanization indicators are the most sensitive of all. Some indicators become more sensitive, for example, variable 6 (infant mortality rate) and the infrastructure variables, while variables 7 and 9 become less sensitive. However the impact of these changes is of little consequence. The above analysis shows certain indicators are discriminatory in defining the less developed states. In the decade 1970-1980 the same indicators are responsible for the low level of development in the less developed states. These indicators are represented by almost all sectors, reflecting again the multidimensional aspect of regional inequalities. The implication is that there is a need to adopt an intergrated approach in regional development in order to reduce the nature and scope of inequalities between the developed and less developed states. REGIONAL INEQUALITIES & DEVELOPMENT 31 Fig. 4 Regions based on Z-Scores A. 1970 and B. 1980. . FACTOR ANALYSIS: THE TREND AND PATTERN OF INEQUALITIES In this study, Factor Analysis is used to identify patterns of relationship between variables and to gain an idea of regional variations in socio-economic development in the country. The Situation in 1970 The correlation matrix in Table 6 shows a relatively large number of high and positive coefficients, particularly variables 5, 16, 17, 18, 19 and 23 which are highly correlated with each other. These variables refer to income, infrastructure, services and the level of urbanisation. Note that variable 13 and 14 (education variables) show weak correlation with all other variables. The factor analysis produces three factors as the more significant ones in that they have eigen values of more than 1.0. These factors account for 83.7 per cent of the total variance. Table 7 shows that Factor 1 loads heavily on almost every variable except 9, 13 and 14 which are social indicators. Factor 1 explains 57.3 per cent of the total variance with an eigen value of 5.2, Factor 2 loads heavily on variable 14 and accounts for 14.5 per cent of total variance with an eigen value of 1.3 and factor 3 loads heavily on variable 13 and explains 12 per cent of total variance with an eigen value of 1.0 Since Factor 1 represents a major proportion of the total variance and appears to some extent to capture at least the interlocking nature of socio-economic development, focus of attention is concentrated on the interpretation of this particular factor. From Table 8 it is obvious that there is wide variation in the factor loadings. Variables 5, 16. 17. 18, 19 and 23 have the highest factor loadings and these are the variables with high CSVs, indicating the high degree of variation of these variables between the states. The least sensitive variables are 13 and 14 (the education variables) which describe the second and third factors and do not reveal the same regional pattern as the other indicators. Factor scores on the Factor 1 are computed (Table 9) to gain some idea of the regional variations in Malaysian socioeconomic development. It can be seen that regional inequalities at the beginning of the decade was high. Generally, the ranking and grouping of the states are identical with those derived from the earlier analysis, with the west coast states occupying the top of the table and the northern and east coast states at the bottom. Based on the factor scores four major regions are demorcated for 1970, with Selangor forming the most developed region. The next region of moderate development comprise Pulau Pinang, Perak. Negri Sembilan, Melaka, Johor and Pahang. Of the two less developed regions, one comprises Trengganu and Kedah and the other, the least developed region of all. comprises Perils and Kelantan. The results of factor analysis again emphasize the eastwest dichotomy in the level of socio-economic development in Peninsular Malaysia (Figure 5). 32 FAUZA ABDUL GHAFFAR Table 6. Correlation Matrix for Selected Variables for 1970 VARIABLE 5 9 13 14 16 17 18 19 23 5 9 1.00 0.50 -0.06 0.16 0.90 0.79 0.81 0.92 0.82 13 0.50 1.00 0.01 -0.21 0.52 0.51 0.32 0.57 0.14 -0.6 0.01 1.00 0.10 0.07 0.04 0.09 -0.11 -0.15 14 0.16 -0.21 0.10 1.00 0.27 0.30 0.14 -0.01 0.18 16 0.90 0.51 0.07 0.27 1.00 0.91 0.79 0.75 -0.77 17 18 0.79 0.32 0.04 0.31 0.91 1.00 0.52 0.70 0.62 19 0.81 0.32 0.09 0.14 0.79 0.52 1.00 0.63 0.86 23 0.92 0.57 -0.11 -0.01 0.75 0.70 0.63 1.00 0.71 0.82 0.14 -0.15 0.18 0.77 0.62 0.86 0.71 1.00 Table 7. Rotated Factor Loadings for Selected Variables for 1970 FACTOR 1 VARIABLES V5 % Per capital GDP ratio to Malaysian V9 V13 V14 V16 V17 V18 V19 V23 average Persons/acute hospital bed Transitional rate primary/Form I Transitional rate lower secondary/Form V Motocars/1000 population Motocycles/1000 population Per capita electricity consumption Per capita water consumption % of urban population 0.99 0.49 0.04 0.25 0.96 0.86 0.85 0.87 0.89 Table 8. Factor Loadings on Factor 1 for Selected Variables for 1970 VARIABLES V5 LOADINGS ON FACTOR 1 % Per capita GDP ratio to Malaysian average Persons/acute hospital bed 0.97 V13 Transitional rate primary/ Form 1 0.04 V14 Transitional rate lower secondary/Form V V16 Motocars per 1000 population 0.24 0.96 V17 Motocycles per 1000 population 0.86 V18 Per capita electricity consumption 0.85 V19 Per capita water consumption V23 % of urban population 0.87 0.88 V9 FACTOR 2 0.49 FACTOR 3 -0.09 -0.718 0.07 0.80 -0.00 -0.02 0.08 -0.29 0.20 -0.45 0.22 0.93 0.22 0.16 0.19 0.00 -0.10 -0.26 The Situation in 1980 To provide comparative results with the 1970 data, a matrix of correlation coefficients is computed for the nine selected variables based on the 1980 data. The correlation matrix in Table 10 shows a number of high and positive correlation. Variables 16, 17. 18, 19 and 23 are highly correlated with one another reflecting the interrelationship between the economic, infrastructure and services and the urbanisation indicators. Variable 23 (level of urbanisation) shows a weak and decreasing correlation with most other variables except variables 5 (income)and 18 (per capita electricity consumption). This might be due to the improvement in the distribution and provision of facilities and services in parts of the country outside the highly urbanised areas. As in 1970, three significant factors account for 86.4 per cent of the total variance. Factor 1 loads heavily on most variables except 9, 13, 14 and 17 and accounts for 52.7 per cent of the total variance. Factor 2 loads heavily on variables 9 and 17 and Factor 3 on variables 13 and 14 (Table11). An analysis based on the interpretation of Factor 1 shows that there are wide variations in the factor loadings. Variable 5 has the highest factor loadings followed by variables 18, 23, 19 and 16. The loadings on variable 17 felled from 0.86 to 0.40, possibly caused by an increase in the ownership of motorcycles especially in rural areas in all the states. The variables with the highest factor loadings are those having a high CSV in the earlier analysis and those with low factor loadings coincide with those of low CSVs (Table 12). Factor scores computed on Factor 1 (Table 13) to facilitate comparison with 1970 show that, although not quite similar to the rankings based on the Z-scores, the regions obtained are identical. Selangor and the rest of the west coast states form the developed regions and the north and east coast states the less developed ones. Perlis replaces Kelantan as the least developed state. An improvement in relative position of Trengganu is notable, a fact attributed to the production of petroleum off-shore which began in the late1970s REGIONAL INEQUALITIES & DEVELOPMENT 33 Table 9. Factor Scores for the States, 1970 STATES FACTOR SCORES Selangor/Federal Territory +2.26 Negeri Sembilan Pulau Pinang Perak Pahang Johor Melaka Terengganu Kedah Perlis Kelantan +0.57 +0.44 +0.38 +0.31 +0.12 +0.69 -0.69 - 0.86 -1.19 •-1.25 DISCUSSION Although the techniques of CSV and factor analysis do not produce exactly similar results, they do provide a common understanding to the nature and scope of the regional-inequality problem in the states in Peninsular Malaysia and the grouping of these states into regions according to the level of socio economic development. An examination of the regional inequality problem in the early stage of national development in Peninsular Malaysia has led to the hypothesis that regional inequalities, unless checked by strong government intervention are likely to increase in the course of development. Although plagued with problems in implementation, several of the regional development policies can be considered to have attained some success in increasing the economic as well as social development level in most of the states in Peninsular Malaysia. This shows that government policies, to a certain extent have been decisive in contributing towards overall development and at the same time arrested further widening of economic inequalities between the states. Despite this relative success, the level of inequalities is still gloring and, more important, part of the improvement may be due to different rates of population growth between the states. The latter may imply that relative decrease in the inter-regional level of inequalities may have been achieved at the expense of corresponding deterioration of the intra-regional and rural-urban levels. Over the decade of overall economic growth and government intervention, there-has been a decrease in the level of economic inequalities. Inequalities were already conspicuous since the beginning of modern economic development in Peninsular Malaysia and future widening in inequalities were, arguably, difficult to continue indefinitely. Fig. 5 Regions based on Factor Scores A. 1970 and B. 1980. REGIONAL INEQUALITIES & DEVELOPMENT 35 Table 13. Factor Scores for the States, 1980 STATES FACTOR SCORES Selangor +2.21 Negeri Sembilan Pulau Pinang Perak Pahang Johor Melaka Terengganu Kedah Perlis Kelantan -0.15 +1.30 -0.22 -0.16 +0.09 -0.01 -0.01 -0.82 -1.38 -0.84 Moreover, investments made to reduce the gap between the developed and less developed states since independence in 1957 had inevitably improved the overall socio-economic level of all the states. Additionally, various programmes had been designed to distribute as wide as possible basic amenities and facilities to improve living standards and the quality of life. Over the decade, these had cumulative impacts on improving socio-economic conditions in the less developed states. Finally official intervention in regional development in favour of the less developed states provided a sufficient base for further development and improvement in socio-economic conditions leading to a reduction in the gap in development between the states in the late 1970s. CONCLUSION This study shows that while development has been achieved in the less developed states, equal or even more rapid development has occurred in the developed states to sustain a disturbing level of regional inequalities. It is argued that although regional development planning has increasingly become an important part of national planning, there seems to be an inherent conflict between transferring resources to poorer regions and the national development goals of political and social integration. While different kinds of projects are implemented in different states, a more comprehensive policy framework is needed for regional planning. Regional plans in the country have drawn on data on the distribution of natural and human resources but generally in an ad hoc manner. It is seen that while the national plan recognizes the goal of general economic and regional balance to overcome such difference the planning process is still geared towards the sectoral rather than a regional approach. Furthermore, the ad hoc nature of regional development planning has led to several problems in regional plan formulation and implementation. For example, development plans tend to compete with one another often resulting in the neglect of opportunities for geographic specialisation and the disregard for development in certain regions. These problems and the fact that several of the •sensitive' indicators were highly discriminatory with regard to the less-developed states, support the need for an intergrated approach to regional development planning. The adoption of the intergrated approach requires the establishment of a regional planning machinery and the introduction of certain strategies applicable to both national and regional planning. There is a need for a policy aimed at achieving a strong and favourable growth of the national economy to benefit the entire population. This implies a regional approach to planning rather than the sectoral approach. To achieve the stated goals in the New Economic Policy, it is relevant that spatial aspects of development be taken into proper account. This will in turn necessitate an adequate spatial framework in the planning process. This spatial framework may be in the form of areal division of the country into various homogeneous regions according to the level of or potentiality for development. The identification of the 'development areas' and the grouping of the states into developed and less-developed ones are based on the per capita GDP of each state. It is stressed that a wider range of socio-economic indicators be used to delineate these groupings. An important measure in moving towards an intergrated approach of regional development planning involves the reorganisation and strengthening of the planning machinery in the form of a Regional Planning Department. This would replace the present structure of regional planning involving- many agencies at different levels but where the power of decision-making rests with the Federal level. Policies on regional development will be decided by a council consisting of members of the highest political authority from both the Federal and state governments. Active involvement of both Federal and state authorities will allow decentralisation of the regional planning process and a wider participation of different interests to work towards the stated goals of national development. REFERENCES Baer. W. (1964), 'Regional inequality and economic growth in Bra/.il', Economic Development and Cultural Change. Vol. XI 1, No. 3, pp. 268-285. Fau/.a Abdul Ghaffar (1982), Regional Inequalities and National Development, (unpublished M.A. Thesis. University of Sheffield ). Fisk. E.D. (1962). 'Special development problems of a plural society '. Economic, Record, Vol. 38, pp. 209-225. Government of Malaysia (1981). Fourth Malaysia Plan 19811985, (Government Press. Kuala Lumpur). Kuznets S. (1955), 'Economic growth and income inequality', American Economic Review. Vol. XLV. pp. 1-28. Nacer, M. (1979), Regional Development in Algeria, (unpublished M.A. Dissertation. University of Sheffield, England). Osborne (1974). Area Development '/Policy, and the Middle City in Malaysia, Department of Geography. Research Paper No. 153, (University of Chicago ). Richardson H.W. (1978), Regional and Urban Economics, (London, Penguin Books). Snodgrass, D.R. (1980), Inequality and Economic Development in Malaysia. (Oxford University Press, Kuala Lumpur). Thomas, W.R. (1957). "The Coefficient of Localization: An Appraisal', Southern Econ. Journal, Vol. 23, pp. 305-308. Williamson, J.B. (1965), 'Regional inequality and the process of national development: A description of patterns', Economic Development and Cultural Change, Vol. 13, pp.3-4