The Treatment Of Eating Disorders As Addiction Among Adolescent

advertisement

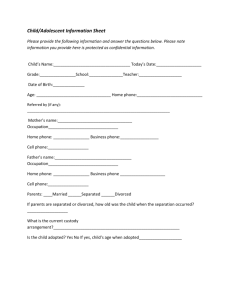

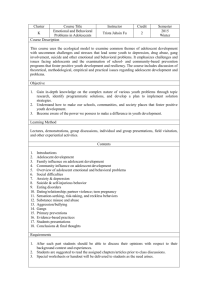

Int J Adolesc Med Health 2002;14(2):269-274. ©Freund Publishing House Ltd. The treatment of eating disorders as addiction among adolescent females Arthur S. Trotzky, Ph.D The Israel Counseling and Treatment Center of the North, Kiryat Bialik, Israel Abstract: As science and medicine enter the new millennium, the influences of genetics and neurochemistry as high-risk determinants in the etiology and development of eating disorders are increasingly manifest in professional literature. Eating disorders are now recognized as major medical and psychiatric problems affecting millions throughout the world. Psychoeducational, cognitive, behavioral, and psychopharmacologic treatments form the basis of most interventions which, for the most part, tend to view the eating disorder as a symptom of underlying psychopathology. The Israel Counseling and Treatment Center of the North has been treating eating disorders as addictive disease by applying the twelve step program of the Anonymous Fellowships as an adjunct to counseling and treatment for those who suffer from compulsive overeating and bulimia. Following the ongoing program of interventions with adults, a counseling group for adolescent females was co-facilitated under the supervision of the author. A co-therapist, in recovery from bulimia and compulsive overeating, uses the twelve step philosophy and served as a role model in this group intervention. Another sample of adolescent females was offered individual counseling adhering to the same addiction treatment approach. Success rates were operationally defined and measured by weight loss in the obese population and the cessation of purging behaviors among bulimic subjects for a sixmonth period. The two adolescent treatment samples had success rates of 62% and 33% respectively. A higher success rate of 71% was observed with adult bulimic females who participated in group counseling. A mean weight loss of 3.9 kg for the small sample of adolescents and a 9.7 kg. mean weight loss for obese adults in treatment was reported. The theoretical basis of the addiction treatment paradigm for eating disorders is presented. Results and problems encountered specific to treating the adolescent population are discussed Key words: obesity, eating disorders, bulimia, food addiction, eating addictions, Israel Correspondence: Arthur S. Trotzky, PhD, The Israel Counseling and Treatment Center of the North, 140/27 Derech Acco, IL-27236 Kiryat Bialik, Israel. Tel: 972-4-8738021. Fax: 972-4-9530023. E-mail: dr@trotzky.com. Website: www.trotzky.com Submitted: January 01, 2002. Revised: January 04, 2002. Accepted: January 05, 2002. INTRODUCTION Many of the approaches to the treatment of eating disorders are derived from traditional psychological theories and systems, and offer cognitive and behavioral interventions as therapeutic methods for dealing with these compulsive behaviors (1,2,3). Early patient histories and unconscious motivations have often been presented as primary determinants in the etiology of the eating disorder and the consequential obesity (4,5). Recent research has suggested a genetic and familial predisposition in the development of anorexia and bulimia (6,7,8). Certain foods have been found to affect the neurochemical balances in areas of the brain and, in certain individuals, certain foods can create a craving for more in a similar manner in which alcohol can create 2 EATING DISORDERS AS ADDICTION craving in the alcoholic (9,10,11). Some attention has been given to compulsive sex and dependency in love and relationships as other manifestations of addictive disease displaying etiology comparable to that of chemical addictions (12,13). Eating disorders such as anorexia, bulimia, and compulsive overeating are seen by many treatment providers as addictions, and methodologies for intervention are being adapted from other addiction treatment paradigms (14,15). The creation of Alcoholics Anonymous in 1935 and the twelve-step spiritual program provided by that fellowship has greatly influenced the attitudes, moral values, and theoretical approaches concerning alcoholism and the treatment of that disease (16). The AA twelve-step program was formulated in the United States and, over the years, has expanded to the treatment of other addictions in numerous other countries throughout the world (17). The AA program is being utilized as adjunct therapy in many rehabilitation centers and has been adopted by groups such as: Narcotics Anonymous, Gamblers Anonymous, Overeaters Anonymous, Eating Disorders Anonymous, Food Addicts Anonymous, and by many other groups suffering from other addictions (15,17). THE ISRAEL COUNSELING AND TREATMENT CENTER In 1990, this author became the first professional in Israel to use the twelve-step program (18) in a rehabilitation setting. As the first clinical director of “Gesher L’Chaim” in Naharihya and “HaDerech” at Kibbutz Gesher Haziv, I supervised a staff of recovering addicts and developed a professional program using this twelve-step model in treating opiate addiction. In 1994, the same twelve-step program and treatment approach was incorporated into treatment interventions at The Israel Counseling and Treatment Center of the North. The center, a private outpatient chemical dependency treatment clinic, became the first clinic in Israel to treat compulsive overeating, anorexia, and bulimia as food and eating addictions following the Minnesota Model of the United States (19) and the Promis Rehabilitation Model in England (20). Since 1994 women suffering from obesity (n=409) and women suffering from bulimia (n=169) were treated in small group settings using the Minnesota twelvestep treatment model. In addition to the adult treatment groups, adolescent females (n=12) were receiving individual counseling for their eating disorders. Because of the successes obtained with adult groupwork using the addiction model, it was decided to offer this medium to an adolescent female population with the hope of observing comparable results. Outcome measures were operationally defined and a group of adolescent females was formed and underwent the same treatment condition as the adults. A comparison of the results is presented as well as a discussion of the methodology and outcomes. Conclusions and recommendations for additional research, for further understanding, and for dealing with these difficult and resistant disorders, are also discussed. METHOD, PROCEDURE AND PARTICIPANTS IN OUR STUDY The participants in this study were all interviewed and accepted to participate as a group for the treatment of food and eating addictions (19,20). The background of each participant was reviewed. Family, education, army service, health problems, current medications, and previous therapy was taken into consideration in order to eliminate additional diagnosis (21). Groups were formed with ten participants and met for a weekly, two-hour session. The groups were controlled for age ARTHUR S. TROTZKY but allowed for both sufferers from bulimia and compulsive overeating to be in the same groups, since the theoretical approach views both disorders as addiction. Adult groups were on-going with a mean time participation of seven months nine days, and were facilitated between 1994-99 (n=578). The adolescent group was solicited by advertisement in the newspaper advertisements. Screening was carried out using the same interview procedure as with the adults. Two candidates with depression and childhood trauma were referred to eating disorders treatment units at the government hospital offering psychiatric supervision and were not accepted for the addiction treatment group. The group (n=10) consisted of adolescent females age sixteen to eighteen, and fully functioning in the eleventh and twelfth grades in high school. The adolescent group was facilitated during the 1998 –99 academic year for an eightmonth period. During the 1997-99 period, twelve adolescent females received individual counseling for eating disorders using the same addiction treatment approach. Between September 1994 and June 1999, 578 adults were treated at the Israel Center and in order to evaluate the results of treatment, they were operationally divided into two groups: Obese (n=409) and Bulimic (n=169). All subjects in the obese group had a BMI (Body Mass Index) greater than 30. All subjects in the bulimic group were seeking help to stop purging behavior. At the start of treatment, weights were obtained and at termination by selfreport. For comparison with the adults and with a similar age group, adolescent females in individual counseling (n=12) were operationally defined as Obese (n=9) and Bulimic (n=3) using the same methods as with the adult group members. Mean weight loss was determined in the obese groups. 3 Success in the Bulimic group was defined as cessation of purging behavior for a six-month period. Percentage rates were used in comparing results. In order to test the efficacy of the group model with adolescents, an advertisement was placed in September 1998 in a Haifa, Israel weekend newspaper presenting group therapy for overweight and/or bulimic females aged 1618 years and using an addition treatment approach. Respondents were interviewed in order to assure group cohesion and to screen for possible emotional problems requiring psychiatric referral. The adolescent group (n=10) was operationally defined as obese (n=8) and bulimic (n=2). Both the adolescent group and the adult group were co-facilitated by an eating disorders counselor who herself was in recovery from compulsive overeating and bulimia, and who utilized the twelve-step program in her recovery. The same parameters for success and mean weight loss were used with the adolescent samples, and percentages were calculated for comparisons. Both group and individual counseling were conducted in the same setting under the auspices of The Israel Counseling and Treatment Center of The North in Kiryat Bialik, Israel. RESULTS FROM OUR STUDY The results obtained for the adult group were much better than those obtained from the intervention with adolescents in individual treatment (see Table 1.). Weight loss was greater for adults, as was the success rate with cessation of purging. However, results obtained for the adolescent group, the rate of success, and weight loss approached those parameters in the adult group but were not at the same levels (see Table 2.). A much greater difference was observed between the adolescent group and results observed in adolescent individual treatment (see Table 3.). Int J Adolesc Med Health 2002;14(2):269-274. ©Freund Publishing House Ltd. Table 1. Adult group and adolescent individual treatment. The Israel Counseling and Treatment Center of the North, Kiryat Bialik, Israel. Group Numbers Adults Bulimic Adults Obese 578 169 Adolescent Bulimic Adolescent Obese 12 9 Mean weight Stopped purging loss in kilograms Numbers 9.7 121 Success rate (%) 71 409 2.5 3 33 3 Table 2. Adult group and adolescent group. The Israel Counseling and Treatment Center of the North, Kiryat Bialik, Israel. Group Numbers Adults Bulimic Adults Obese 578 169 Adolescent Bulimic Adolescent Obese 10 8 Mean weight Stopped purging loss in kilograms Numbers 9.7 121 Success rate (%) 71 409 6.0 5 62 2 Table 3. Adolescent group and adolescent individual treatment. The Israel Counseling and Treatment Center of the North, Kiryat Bialik, Israel. Group Numbers Mean weight loss in kilograms Stopped purging Numbers Success rate (%) Group Bulimic Obese 10 8 2 6.0 5 62 Individual Bulimic Obese 12 9 2.5 3 3 3 Int J Adolesc Med Health 2002;14(2):269-274. DISCUSSION Results seem to indicate that the addiction group treatment intervention, which had been effective in treating compulsive overeating and bulimia in adults, could be utilized beneficially with an adolescent population. In addition, the effect of group intervention produced better results than individual counseling for adolescent females in this study. The addiction treatment paradigm is able to obtain positive results both in weight loss and in helping to stop purging behavior in females suffering from bulimia. The absence of group influence might have been a factor distinguishing results obtained among adolescent treatment variables. The second step of the twelvestep program emphasizes the importance of a power other than that of personal suffering, and this certainly applies to influences of a group (15). Individual treatment did not provide a recovering food and eating addict as a co-therapist and model for the subjects, and her presence might have contributed to the comparatively better results observed in the group situation. In addition to the admission of powerlessness in step one of the twelve steps, one must also be aware of the serious consequences of addiction (15, 22). The adult population has most likely suffered consequences of overeating and bulimia to a greater extent than adolescents, and may consequentially be more motivated to apply a recovery program to his or her life. Since adolescence is a period of selfexpression and self-identification, addictive thinking (22) may interfere with admission of powerlessness and the need to rely on others in order to recover (15). As the addiction treatment model is spiritual in nature, (18) differences in openness and readiness to become involved in spirituality may also be a determinant of the differences ©Freund Publishing House Ltd. CONCLUSION The use of the twelve steps as adjunct therapy in the treatment of eating disorders has generated positive results in this study. Effectiveness with adult group intervention has been shown to produce less favorable but similar results when utilized with adolescent females. The results of this study suggest that group intervention with adolescent females seems to be more effective than individual therapy in treating compulsive overeating and bulimia. REFERENCES 1. Bruch H. Eating Disorders: Obesity, anorexia nervosa and the person within. New York: Basic Books; 1973. 2. Johnson C, ed. Psychoanalytic treatment of anorexia nervosa and bulimia. New York: Guilford;1991. 3. Zerbe K. The body betrayed. A deeper understanding of woman, eating disorders and treatment. California; Gurze, 1993. 4. Bemporad J, Herzog D, eds. Psychoanalysis and eating disorders. New York: Guilford; 1989. 5. Gilbert S. The Pathology of Eating: Psychology and Treatment. London: Routledge and Kegan; 1986. 6. Bulik C, Sullivan P, Kendler K. Heritability of binge-eating and broadly defined bulimia nervosa. Biol Psychiatr 1998; 44(12):1210-8. 7. Kendler K, MacLean C, Neale M, Kessler R, Heath A, Eaves L. The genetic epidemiology of bulimia nervosa. Am J Psychiatr 1991; 148 (12):1627-37. 8. Kaye W. Persistent alterations in behavior and serotonin activity after recovery from anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1997; 28:162-178. 9. Katherine A. Anatomy of a food addiction: The brain chemistry of overeating. California: Gurze; 1991. 6 EATING DISORDERS AS ADDICTION 10. Rogers P, Smit H. Food craving and food addiction: a critical review of the evidence from a biopsychosocial perspective. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2000; 66:3-14 11. Ludwig D, Majzoub J, Al-Zahrani A, Dallal G, Blanco I, Roberts S. High glycemic index foods, overeating, and obesity. Pediatrics 1999; 103(3): 26. 12. Beattie M. Codependent no more. Minnesota: Hazelton; 1992. 13. Mellody P. Facing love addiction. California: Harper; 1992. 14. Lefever R. How to combat anorexia bulimia and compulsive overeating. London: Promis; 1988. 15. Elizabeth L. Twelve steps for overeaters. Minnesota: Hazelden; 1993. 16. Alcoholics Anonymous. New York: Alcoholics Anonymous World Service; 1976. 17. Lefever R. How to identify addictive behaviour. London: Promis; 1988. 18. Twelve steps and twelve traditions, 38th ed. New York: Alcoholics Anonymous World Services;1988. 19. Spicer J. The Minnesota Model. Minnesota: Hazelden; 1993. 20. Lefever R. Kick the habit: Overcoming addiction using the twelvestep programme. London: Carlton Books; 2000. 21. Miller M. Treating coexisting psych- iatric and addictive disorders. Minnesota: Hazelden; 1994. 22. Twerski A. Addictive thinking. Minnesota: Hazelden; 1990. FURTHER SUGGESTED READING 1. Black C. Double duty, dual identity: Raised in an alcoholic/dysfunctional family and food addicted. Denver, Co: Mac Publishing,1992. 2. Black,C. It will never happen to me. Denver, Co: Mac Publishing, 1982. 3. Black C. Repeat after me (2nd Ed). Denver, Co: Mac Publishing, 1995. 4. Carnes PA. Gentle path through the twelve steps. Minnesota, Minn: Hazelden, 1993. 5. Christian S. Working with groups to explore food and body connections. Minnesota, Minn: Whole Person Associates, 1996. 6. Cohen MA. French toast for breakfast: Declaring peace with emotional eating. California: Gurze, 1995. 7. Roth G. When food is love: Exploring the relationship between eating and Iitimacy. New York: Penguin/Plume, 1992. 8. Sacker I. Dying to be thin. New York: Warner Books, 1987. 9. Twerski A. The thin you within you. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 1997. 10. Twerski A. Waking up just in time. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin; 1990.