20th Century Cities In The Philippines

advertisement

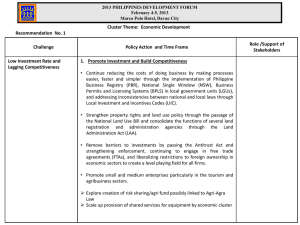

Globalization And Localization In The 21st Century: The Case of Mindanao Regions in the Philippines 1/ Sophremiano B. Antipolo 2/ Globalization has, indeed, emerged as one of the most powerful phenomena shaping our socio-economic environment. In this 21st century, matters concerning globalization present new challenges for rural, urban and regional development planners throughout the world. In the Philippines, with the enactment and implementation of decentralization, the central challenge becomes twofold: confronting global competition and improving local governance. This is because globalization is accompanied with localization that tends to erode the regulatory power of nationstates. This paper reviews the implications and the challenges posed by globalization and attempts to examine and demonstrate how the decentralized cities in the Mindanao regions of the Philippines continue to gear towards such challenges in this century. Introduction Globalization and localization: to what extent will these paradoxical and co-existing forces determine the course of urban and regional planning? And what are the challenges they pose upon the decentralized cities in the 21st century? Globalization has recently emerged as one of the most powerful phenomena shaping our socio-economic environment. In this 21st century, matters concerning globalization present new challenges for urban and regional planners throughout the world. Indeed, increasing globalization of economic activities necessitates a critical re-evaluation of existing urban and regional development strategies which seek to improve the quality of life and to reduce spatial inequalities. In the Philippines, with the enactment and on-going implementation of the decentralization policy through the 1991 Local Government Code -- hereafter referred to as the Local Code -- the central challenge becomes twofold: (1) facing global competition, and (2) improving local governance. This is because globalization is accompanied with localization and, in the process, tends to erode the regulatory power of nation-states. For one, globalization is closely related to the localization strategy of transnational corporations (TNCs) for their business activities. Under these circumstances, the general propensity of TNCs is to integrate their business activities with the local economic environment where their establishments are located. Globalization and localization, then, signal the need to emphasize the active role of spatial planning in determining regional and economic development policies and strategies. In this context, the performance of rural, urban and regional economies are largely dependent upon the capacity and capability of local government units. In this paper, I shall attempt to examine and demonstrate how the cities under the decentralized form of governance can gear towards the challenges of globalization and localization, using the case of Mindanao Regions in the Philippines. In particular, the paper is organized in seven parts. It begins with a review of the spatial implications of globalization in order to put into context the more specific challenges for urban and regional planning. Part 2 presents a reconciliation of the issue surrounding "balanced growth" and "inequality". Part 3 provides a brief elucidation on how decentralization can be pursued by strengthening urban-rural linkages. Part 4 reviews the current MediumTerm Philippine Development Plan to provide a macro-perspective concerning the country’s response to the challenges of globalization. Part 5 discusses the spatial and urban development patterns of the Philippines “before” and “during” the 20 th century to provide some reference points for examining the potentials of Mindanao cities. Part 6 demonstrates how the decentralized cities in the Mindanao Regions are gearing towards the challenges of globalization and localization in the 21st century. Paper. Part 7 concludes this The Spatial Implications and Challenges Of Globalization and Localization Lee and Kim (1995)3/ alerted us of at least three distinctive impacts of globalization on spatial configuration and regional development. First, the weakening of nation-states reduces their ability to control the movement of capital, products, and labor across national boundaries and to distribute resources to achieve territorial equalization. They argued that this situation can lead to the intensification of competition among regions and localities and are likely to expand spatial inequalities. There will be greater inequality between cities and rural areas and among cities of different sizes. In addition, regions and local units will become more important economic units operating on a global scale rather than the nation-states. Thus, globalization will require a new approach to policymaking based on a “partnership” with localities and regions, whose local knowledge is far superior to that of the central government (Dubford and Kafkalas, 1992)4/ . Localization of the economy and decision-making mechanism are also closely related to the corporate globalization and localization strategy of business activities. Transnational corporations have tended to seek the expansion of their market and production spaces on a global scale but their transnational plants have tended to be integrated with local business environments to make maximum use of resources where their plants are located. No wonder, Swyngedouw (1992)5/ reiterated Andrew Mair (1991) who coined the term ‘glocalization’ to characterize this paradoxical co-existence of globalization and localization. Also, the weakening of the nation-states has tended to expand the role of the private sector in regional and local development. Over time, the public sector is increasingly dependent upon the private sector, even for the provision of infrastructure. Second, the increase in the mobility of capital is likely to increase outflows of domestic capital to other countries and inflows of foreign capital. The increase in outflows of capital may lead to a rapid decrease of production activities in industrialized areas, particularly in areas where labor intensive industries are concentrated and also a reduction of factory movements between industrialized and less industrialized areas. Since the industrialization of less prosperous areas has greatly relied on the demand created in industrialized regions, the increase of capital outflows is likely to reduce the potentiality of industrial development in the less prosperous regions. Furthermore, the increase of foreign capital inflows may undermine the self-sufficiency of the local economic development base, since local economic activities controlled by foreign ownership is increasing. Thus, one of the major challenges confronting future regional development is to maintain stability and self-sufficiency in the local economy during the process of globalization. Recent empirical studies show that the creation of industrial districts, localities programs can be an effective development strategy for the localization of the economy in the process of globalization (Amin, 1992)6/. Third, there is a global spread of a capitalist mode of production based on flexible production technology. In economic sense, globalization was initiated by advanced economies as a response to the crises of post-war capitalist production system. This system was based on capital intensity, standardization of production and unionized labor organisation. This Fordist mode of production has been transformed into a PostFordist mode based on flexible production technology. A new capitalist production system will move towards flexible specialization in high valued-adding activities and specialized producer services. Rapid changes in technology and market demands have created uncertainty and risk in the investment climate. To adapt to this changing environment, manufacturing firms have increased vertical and horizontal disaggregation of their organizations and established linkages with other organizations. Thus, in a flexible regime, firms favor business environments in which they can easily obtain professionals and scientists and establish cooperative production systems or networks 2 with other organizations (Leborgne & Lipietz, 1988)7/. Also, in situations of greater decentralization of economic activities, decision-making tend to be tied and rooted in a particular place while they maintain immediate global contacts. “Balanced Growth” and “Inequalities” Reconciled Prominent in the quest for decentralization as in the approach for inter-regional planning are the terms “balanced growth” and “regional balance”. The achievement of a regional balance between people, jobs, and environment is a fine rhetoric, but the term ‘balance’ is somewhat confusing and has been given a variety of meanings. It could mean that poorer regions should grow faster than the rich ones so that their income levels tend to equalize; in this context, ‘balance’ means ‘convergence’. Another interpretation could mean that the rate of growth in the poor regions should keep pace with that of the prosperous regions. In this case, the nation and the constituent regions would grow at the same rate, but as a consequence of this would be a widening of absolute income differentials between the rich and the poor regions. To settle the matter of operational meaning of the terms in relation to the quest for equality, Friedmann (1978)8/ offers that by the word ‘balance’, no rigid mathematical balance is needed. What is meant instead is a sense of systematic inter-relations between and among regions, between rural and urban areas in which their notorious differences or ‘inequality’ in levels of living and opportunity will become progressively less pronounced. Decentralization By Strengthening Urban-Rural Linkages While on professional affiliation with the Infrastructure and Urban Development Department at the World Bank Headquarters in Washington, D.C., Antipolo (1989)9/ conducted an international survey on rural-urban linkages. The survey pointed to an ultimate general recommendation – pursue decentralization. Hereunder is a brief summary of some lessons learned out of the empirical evidence that bear relevant implications for pursuing decentralization. Faced with the increasing concentration and economic activity in few large cities, policy-makers have sought to implement spatial policies to decentralize population and employment from the large urban centres. In most developing countries, spatial policies have taken various forms, including outright prohibition of manufacturing activities by rule of laws, various fiscal incentives and infrastructure investments (Lee, 1989)10/. The most important services and facilities for rural development within a region cannot be merely scattered over its landscape, but must be located in towns and cities whose sizes are sufficiently large and diversified to offer economies of scale and proximity. In this connection, decentralization through the development of market towns, small and intermediate cities is important not only for the efficient location of services and infrastructure needed to support rural and agricultural development, but also because these urban centres function as markets for agricultural goods, as channels through which agricultural products from rural areas are distributed to larger urban markets, and as source of off-farm employment (Owens et. al., 1976)11/. Rural and agricultural development stimulates growth of small and intermediate cities. Studies in the Philippines have shown that the impact of agricultural development on urban growth is particularly strong at the lower end of the settlement hierarchy. This implies that governments can stimulate the growth of small and intermediate cities by decentralizing agricultural programs and rational allocation of investments in support services, including infrastructure (Gibb, 1984)12/. An alternative approach to spatial development should seek to move away from highly skewed pattern of population and resource distribution found in the primate city toward a more diffused or decentralized pattern of urbanization in which the small and intermediate urban centres play important role in integrating urban and rural economies (Friedman, 1981) 13/. 3 The strategy for strengthening of urban-rural linkages is discussed in the Philippine Medium-Term Development Plan as well as in the Philippine Framework for Physical Development . The Current Medium-Term Philippine Development Plan: Responding to the Challenges of Globalization The current Medium-Term Philippine Development Plan is anchored on the twin strategies of people empowerment and global competitiveness within the context of sustainable development. On one hand, the strategy of people empowerment has its roots from the restoration of Philippine democracy through the world acclaimed “People Power at EDSA”14/ in 1986 after over two decades of dictatorial regime. On the other hand, the strategy of global competitiveness aims to respond to the rapid development in the international trade environment such as the establishment of the World Trade Organization (WTO), liberalization, deregulation, and facilitation initiatives under the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), and the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC). Strengthening the Mindanao Cities for Global Competition The Philippines recognizes the need to increase the capacities of Mindanao urban centres to be more competent for global competition. To further enhance their capacities, the Medium-Term Development Plan has adopted the following key development strategies, namely: (1) full physical integration of Mindanao into the global economy by infusion of the much needed infrastructure support that can consolidate the region’s potential into a vibrant economic unit; and (2) strengthen Mindanao’s direct global trade and economic links with the rest of the world through the implementation of enabling policies. This approach is intended to encourage more inflow of private sector investments -- both local and foreign -- to spur economic growth. At the same time , Mindanao cities shall continue to provide critical services such as health service delivery, tertiary education, inter-Mindanao regional coordination and international collaboration. To reinforce the key development strategies, three sub-strategies have been identified to strengthen rural-urban linkages and, in the process, minimize rural-urban, and interregional disparities: (1) rural-focused strategy - identification of rural satellite centers to serve as trading posts of consumer goods and raw materials and providing them with adequate physical and social infrastructure; (2) multi-polar strategy - identification of growth poles or regional agro-industrial centres as recipients of foreign investments; and (3) growth corridor strategy - promotion of investments along existing main transport routes or through communication networks Through the adoption of a rural-focused strategy, investments will be poured into the People’s Industrial Estates (PIEs) set within the identified rural satellite centres. These centres serve as trading posts of consumer goods as well as provide the necessary raw materials for processing at the urban centres. The second sub-strategy -- multi-polar development -- involves the identification, promotion and development of growth centres within each region which will relate with the key partners in East Asia and even extending up to Australia. These identified urban centres will be the main recipients of local and foreign investments. Finally, the growth corridor development sub-strategy involves the promotion of investments along the existing and potential transport routes as well as through communication networks connecting two or more growth poles. Decentralized Form of Governance The MTPDP emphasizes that for the twin strategies to work, policies flowing from such strategies must conform to the guiding principles of decentralization, democratic 4 consultation, and reliance on non-government initiatives Specifically, the MTPDP provides that: (NEDA Board, 1992)15/. In governance, a direct outcome of the strategy of empowerment is the principle of decentralization and subsidiarity. Lower levels of government (regional and local) must be allowed to set priorities and decide matters in their own spheres of competence. Indeed, in the 1990s -- towards the end of the Aquino administration and for much of the Ramos presidency -- three major events had taken place in the area of politicoadministrative development that bear relevance to decentralization in the Philippines: 1) The Local Government Code (LGC) was enacted in October 1991 to carry out the government’s commitment to local autonomy and people empowerment. The Local Code allocates substantive portion of government funds and devolves extensive powers to the local government units (LGUs). 2) Executive Order 505 was passed in February 1992 to make the Regional Development Councils (RDCs) more responsive to the increased needs of local government units (LGUs) for technical assistance in the areas of planning, investment programming and project development. Specifically, the key features in the reorganized RDCs are the inclusion of the legislators (congressmen) as regular members, and the addition of some functions related to the devolution process. 3) Executive Order 512 was issued in March 1992 creating the Mindanao Economic Development Council (MEDCo) to ensure the increased viability of programs and projects in the four administrative regions in Mindanao, including the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM). The Philippines is, perhaps, the only country in Southeast Asia that has implemented political decentralization (i.e., devolution) through the enactment of the 1991 Local Code. And while the time frame of the current national plan is winding up, indications are clear that the successor MTPDP for the plan period, 2010-2014, will remain anchored on the twin strategy above-stated as the newly-elected Benigno Simeon C. Aquino III has vowed to continue the worthy initiatives of the past administrations. Spatial and Urban Development In the Philippines The first three quarters of the 20th century saw profound changes in the Philippine economy. Over the period 1900-1975, the country experienced a more than quintupling of its population and a roughly twenty-one-fold increase of the total number of industrial establishments (Paderanga and Pernia, 1978)16/. This was accompanied by a structural transformation of the economy as exemplified by shifts away from some industries towards others. For instance, estimates of gross value added indicate that in 1903, the primary (agricultural) sector accounted for 55 per cent of the total output, followed by the tertiary (service) sector with 32 per cent, and the secondary (industrial) sector with 13 percent. By 1975, the primary sector’s share had declined to 27 per cent, with the tertiary and secondary sectors contributing expanded shares of 40 and 33 per cent, respectively. Running parallel to the structural transformation of the economy was a changing spatial configuration. In general, the seventy-five-year period saw a secular increase in the primacy of Metropolitan Manila – the National Capital Region (NCR). Already the administrative capital and economic centre of the country at the turn of the century, Manila steadily became more dominant especially in the postwar period. These developments are traceable to policy shifts17/. The forces that shaped the overall growth of the economy and its accompanying spatial configuration necessarily also left deep imprints on the system of cities. Cities have developed in varying ways and at different rates corresponding to their roles in the regions and in the country as a whole. They tend to reflect the importance of their regions of influence as well as their relationship to the macro-economy. The predominance of Metropolitan Manila, for example, manifests its centrality in the economy. 5 The Hierarchy of Settlements Before the 20th Century The pattern of settlements during the pre-colonial period reflected the prevailing institutional arrangement and the economic activity in the settlements. Most of the largest communities were coastal villages engaged in extensive external trade. Manila (in Luzon) and Cebu (in the Visayas) were large agricultural and fishing villages with strong secondary trade functions. Urban clusters were established during the Spanish regime to act not only as trading centres but also as defensive points from which control of indigenous villages was possible. Doeppers18/ identified a three-level hierarchy of settlements then prevailing: (a) capital city with Manila directing the affairs of the country; (b) provincial centres (ciudades and villas) were centres of military, political, and ecclesiastical control composed of Cebu, Naga, Nueva Segovia, all ciudades and villas in Panay, and Fernandia (Vigan); and (c) central church villages or cabeceras which became the focal points of activity and cultural change. These settlements were given functional importance and social prestige which distinguished them from other settlements. In the late 19th century – the end of the Spanish colonial period – the urban hierarchy that evolved mirrored the economic development of that period. Consistent with the development pattern at that time, the urban hierarchy in 1900 was such that urban places were not evenly distributed. Almost half of the third-ranked towns, for instance, were concentrated in Southern Tagalog and Central Luzon and the secondranked cities were found in the Visayas namely: Cebu and Iloilo. The Urban System in the First Half of the 20th Century Since the turn of the 20th century, the urban system has been growing both in terms of their proportion to the total population and the number of urban places. Likewise, there had been remarkable mutations within the urban hierarchy during the seventy-five year period. Membership in the top thirty urban places, for example, has continually changed, implying that centres of population and economic activity have been shifting20/ The earlier census years had more top central places located in Luzon and in the other traditional agricultural regions (the Visayas), reflecting the earlier development of places closer to the seat of government. The later years show the representation to be more evenly balanced among the regions. Urbanization In the Second Half of the 20th Century The urban population of the Philippines grew at an average of 4.43 per cent from 19482000 (Table 1). However, the distribution of urban population has been highly skewed, with Metropolitan Manila or the National Capital Region (NCR) accounting for about 27 per cent of the total urban population in 2000. The NCR has been the singular focus of all economic, social, political, and cultural activities in the Philippines. Its primacy has been reinforced to a level of a “mega city” that it can hardly meet the demands of its ever-growing population. At present (2010), the population of Metropolitan Manila is estimated at about 14 million. As it is, there are telling signs that the available urban services and facilities have deteriorated. 6 Table 1 URBAN-RURAL DISTRIBUTION OF POPULATION, 1948-2000 (Levels, Per cent Shares, and Growth Rates) YEAR TOTAL POP. (M) GROWTH RATE 1948 1960 1970 1975 1980 1990 2000 19.23 27.09 36.64 42.07 48.20 60.68 76.50 Source: (%) URBAN POP. (M) URBAN % TO TOTAL 2.89 3.01 2.80 2.75 2.33 2.46 5.83 8.07 12.07 14.04 17.94 29.64 37.25 30.32 29.89 32.94 33.37 37.22 46.85 48.70 URBAN POP GR (%) 3.74 4.10 3.06 5.02 5.14 5.39 RURAL POP (M) RURAL % TO TOTAL RURAL POP GR (%) 70.67 19.06 24.61 28.02 30.16 31.05 39.25 70.36 67.17 66.60 62.57 53.15 51.30 3.57 2.58 2.62 1.48 0.58 0.67 Census of Population and Housing National Statistics Office Furthermore, the primacy of Metro Manila (the National Capital Region or NCR) has brought about regional imbalance in terms of economic growth as well as urban development. In view of this, the Philippines has adopted regional development both as a goal and strategy in the attainment of balanced development in the country with urban development as a critical element of the country’s regional development. Pursuant to a Presidential instruction, the National Economic and Development Authority (NEDA) is in the process of formulating the National Urban Policy which aims to focus on policy measures that would strengthen the roles of urban centers in national and regional development, as well as improve the living conditions in urban areas. Mindanao Cities: Gearing Towards The Challenges of Globalization In the 21st Century The 21st century is, indeed, expected to be a world of cities. The United Nations projected that about half of the world’s population or over 5 billion people will be living in urban settlements. Under the current Local Code, urban centers throughout the Philippines are being primed to serve as new hubs for industrial development. Most notable is the development in General Santos City, one of the cities in the Mindanao. General Santos City has gained the status as a “boom city” with the influx of both population and economic activities in the area. This development may be attributed to the dynamism of local government leadership and aggressiveness of the private business sector. In addition, other cities from the different regions in Mindanao such as Davao, Cagayan de Oro, Zamboanga, Cotabato, and Iligan, have shown significant economic activities. And to further enhance the development in these growth centres, a new dimension to interregional cooperation is taking place and this is referred to as “regional cross-border cooperation”. Better known as the BIMP-EAGA (Brunei-IndonesiaMalaysia-Philippines East ASEAN Growth Area), it is the Philippine’s initiative to position Mindanao as a gateway to sustained international economic cooperation (Sobrepena, 1995)19/. Cities And Global Competition While there has been a proliferation of academic papers and discussion concerning globalization, a unified approach to defining the words “global city” and "world city" has remained a difficult task. Of late, though, “global city” and “world city” have been used interchangeably in urban and regional studies literature. The term “world city” was denoted as the centre of specific world economies -- the logistic heart of its activity (Braudel, 1984)20/ while others denoted “global cities” as nodal points to 7 coordinate and control global economic activity (Sassen, 1986)21/. Some define such cities as the location of the institutional heights of worldwide resource allocation, concentrating the production of cultural commodities that knit global capitalism into a web of symbolic hierarchy and interdependence (Ross, 1983)22/. Recent literature indicate that the factors which brought about a world-city status include the following (King, 1990)23/: (1) strength of the economy to which the world city belongs; (2) location in relation to zones of growth or stagnation in the international economy; (3) attraction as a potential basing point for international capital; and (4) population size. In an attempt to resolve the definition of “world city”, Friedman (1986)24/ devised the following specific criteria to determine world city status: (1) major financial center; (2) site of headquarters for transnational corporations, including regional headquarters; (3) international institutions; (4) rapid growth of businessservice sector; (5) important manufacturing centre; (6) major transportation node; and (7) population size. Using this set of criteria, only Metropolitan Manila is included in the roster of secondary “world cities”. And the cities in Mindanao can hardly, as yet, be described as global or world cities. However, certain characteristics have started to appear pointing to the direction towards future globalization of these urban centres. Urban Development Potentials In Mindanao Regions In the traditional context, inter-regional planning in the Philippines aims to integrate the development of neighboring regions within the country. With the objective of preparing for globalization, development efforts have been outward-looking, transcending regional boundaries, and even going beyond the geographic boundaries of the country. Thus, in pursuit of the strategy of global competitiveness, the Ramos Government then had initiated and decided to showcase this strategy through the development of Mindanao. As one of the visions of his administration, the strategy of global competitiveness aims to strengthen the country’s capacity to produce an increasing range of products and offer opportunities comparable to those in the rest of the world by preparing Mindanao as the Philippine’s gateway to sustained global economic cooperation. Mindanao: Gateway To A Sustained Economic Cooperation Located in the south, Mindanao is the second largest island in the Philippines. It comprises about 102,043 square kilometers of land area. Ideally situated outside of the typhoon belt, Mindanao enjoys a generally fair and tropical climate throughout the year making it the nation’s leader in agriculture and agri-based industries. Mindanao is composed of four administrative regions and one autonomous region comprising 23 provinces and 19 cities. Mindanao is the site of one of the world’s richest nickel deposits, while accounting for three-fourths of the country’s iron reserves and a third of its coal resources. Forests still cover two-thirds of the island. And apart from the usual agri-based industries, there are heavy industries along the northern coast producing sintered iron and steel plates. Mindanao also remains to be the “fruit basket of the Philippines”. Coconut and banana exports contribute largely to the island’s income. It registers a manpower reserve of 10 million with a functional literacy rate of 94 percent. Moreover, the area is an ideal blend of vast frontiers and highly urbanized centres of commerce and industry suitable for the development of viable tourism industry and a business climate for investors (NEDA, 2006)25/ . Urbanization and Urban Development Trends Mindanao has been urbanizing significantly in recent years. Pernia et. al. (2000)26/ noted that the urbanization levels of Northern Mindanao (Region X) and Southern Mindanao (Region XI) alone, doubled in three decades (Table 2). Outside of Metro Manila (the National Capital Region), these regions posted the third and fourth highest urbanization levels among all other regions in the Philippines in 2000, next to Central Luzon (Region III) at 60.3 per cent and Southern Tagalog (Region IV) 8 Table 2 LEVELS OF URBANIZATION AND ANNUAL RATES OF CHANGE BY REGION, PHILIPINES, 1970-2000 (In Percent) REGION LUZON NCR Region I Region II Region III Region IV Region V VISAYAS Region VI Region VII Region VIII MNDANAO Region IX Region X Region XI Region XII PHILIPPIN 1970 1980 1990 2000 1970-80 1980-90 1990-2000 98.1 17.6 14.1 26.5 26.8 21.9 100.0 19.4 14.1 30.2 30.6 19.2 100.0 23.8 16.7 41.8 37.1 21.9 100.0 36.6 24.5 60.3 51.1 31.2 0.19 0.97 0.00 1.31 1.34 -1.33 0.00 2.04 1.66 3.26 1.91 1.34 0.00 4.30 3.85 3.66 3.20 3.54 30.5 22.2 18.9 26.7 27.9 19.4 28.4 32.1 21.8 35.8 40.4 31.2 -1.34 2.29 0.27 0.62 1.41 1.17 2.31 2.29 3.57 16.8 20.2 20.9 N.A.* 15.8 20.9 26.6 15.6 17.4 27.1 33.9 18.9 30.7 43.4 47.4 25.3 -0.65 0.34 2.41 N.A.* 0.99 2.61 2.41 1.92 5.70 4.69 3.36 2.90 29.8 31.8 37.5 48.6 0.66 1.64 2.59 * Not Available Source of Basic Data: National Statistics Office at 51.1 per cent. Worth noting are the urban growth rates of all four Mindanao regions which posted higher than that of the national average in 1990-20007/. Western Mindanao (Region IX) had the highest growth rate at 5.70 per cent followed by Northern Mindanao (Region X) at 4.69 per cent. This trend may be attributed to the fast growth of cities in Mindanao such as Marawi City in Central Mindanao which was ranked second highest growth rate at 5.30 percent in 2000, and followed by General Santos City in Southern Mindanao (Region XI) at 5.20 percent. Other cities in Mindanao showed notable growth rates. Development Potentials of Mindanao Despite its natural and human resource potentials, the utilization of the island’s land resources is not yet fully maximized. It is also strategically situated to take advantage of the vast and growing trade opportunities particularly with its ASEAN neighbors. The past performance of Mindanao’s economy speaks eloquently of its potentials. Over the past years, its percentage share in the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has grown steadily. This growth has been propelled mainly by industry -- the fastest growing sector in the economy. Mindanao Cities As Focal Points for International Trade Despite the economic slowdown brought about by the global meltdown, and the El Nino phenomenon, Mindanao contributed 19.8 per cent to the Philippine gross domestic product (GDP) and registering a 2.7 percent real growth by the end of 2010. Such economic resiliency can be accounted for by its rapidly urbanizing cities, namely: Zamboanga, Cagayan de Oro, Davao, Cotabato, and General Santos. These cities have grown dramatically in terms of population size and economy in the past decades. Except for General Santos City, all four cities have been designated as regional centres, serving as focal points for administrative and trade relations, as well as centres for health service delivery and tertiary education. In fact, all cities are equipped with some level of infrastructure facilities viable for external linkages and exchanges, such as airports, seaports, road network and telecommunication system. Over the years, Mindanao experienced the influx of 9 industries which are resource-based or oriented towards domestic consumption. The top manufacturing activities include: (1) food and beverage manufacture; (2) wearing apparel; (3) wood and wood cork products; (4) furniture and fixtures repair; (5) industrial chemicals; (6) rubber products; (7) non-metallic mineral products; (8) iron and steel basic industries; (9) machinery except electrical; and (10) cement. As the cities of Mindanao prove to be viable centres of trade and external linkages, these industries locate along its periphery. Philippine corporations which have entered the global market have also invested in these industries, such as the San Miguel Corporation, RFM Corporation and DOLE Philippines. To further sustain these economic activities of the private sector, large Manila-based universal banks have extended their services to these cities. Because of the increase of exports of products, such as fresh and processed fruits and canned fish, international air and seaports have been upgraded and international flights have began. This has brought about strong economic ties between Davao City of the Philippines and Manado of Indonesia and Zamboanga City of the Philippines and Labuan of Malaysia, among others. From these developments, one can conclude that these cities have begun to position themselves in the global competitive market. These cities shall serve to catalyze the process of agri-industrialization in the suburban areas and regions. With the increasing role of these cities in processing, service delivery, financial transactions, transshipment activities, they shall likewise serve as gateways of Mindanao in the East ASEAN Growth Area (EAGA). Zamboanga City’s link with East Malaysia through Labuan, Davao City’s with Manado in North Sulawesi, Indonesia and General Santos City’s with Maluku, Indonesia shall be intensified through trade and cultural relations. Mindanao and East ASEAN Growth Area An innovative approach to urban and regional development planning is being pioneered in East Asia (Sobrepena, 1994)28/. The approach, called regional cross-border cooperation, adopts outward-looking, transnational solutions to domestic concerns like depressed regions, inequitable distribution of growth and urban core-periphery relations. It was brought to fore when China, through economic relations with neighboring countries, attained high economic growth rates. Its underlying concepts crystallized when Singapore initiated cooperative ties with Johore, a southern state of Malaysia and the islands of Riau in Indonesia to form the Singapore-Johore-Riau (SIJORI) Growth Triangle. Since then, Asian countries have increasingly tried to replicate regional cross-border cooperation, also known as the growth triangle approach. Toward this end, the urban centers play a major role as they are expected to stimulate growth in the area being the existing primary centers of economic activities. Rationale and Concept of the Planning Approach Recent transformations in the foreign trade policies of European and Western countries as manifested in the recent emergence of trading blocs such as the European Community (EC) and the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) have freed these countries from restrictions that isolated them from one another for years. In the process, developing Asian countries have increasingly become concerned about the impacts these changes would have on Asian exports and capital inflows. The formation of the EC and NAFTA, therefore, created a need for counterpart Asia-Pacific groupings in a form that had to be different from existing trading blocs because of fundamental problems such as insufficient volume of trade among Asian countries, differences in trade policies, similar factor endowments, geographical features and political considerations. What has resulted are various proposals for alternative ways to group Asian countries. The growth triangle approach is a transnational economic zone spread over large yet defined neighboring areas covering three or more countries. At the vertices of the triangle are he existing centers of trade and economic activities. Within the zone, the 10 resource endowments of each member country are trapped based on comparative advantage to spur overall external trade and investments and channeled through existing vertices. In addition, these centres are mobilized to serve as linkages of opportunity, transportation, communication, and tourism. Hence, unless these centres are strengthened, linkages with the other centres will not progress. This manifest the crucial role played by cities or urban centres. The development activities in the growth triangle are primarily implemented by sub-national government units. In terms of utilization of foreign capital, the participants of the growth triangle are classified either as a recipient or investing groups. Recipient groups are countries or regions of countries which complement the inflow of foreign investments by offering land, labor, and other natural resources while investing groups are those which provide capital, technology, management skills and at times, access to foreign markets. Economic cooperation in the form of the growth triangle approach can thereupon overcome the fundamental problems associated with the formation of a trading bloc in Asia. Specifically, the advantages of growth triangles are (1) lesser economic and political risk; (2) lower organizational cost; (3) wider scope of trade; and (4) attractiveness to foreign investment (Sobrepena, 1995)29/. Geographical Coverage The East ASEAN Growth Area covers Brunei Darussalam, the provinces of North Sulawesi, East and West Kalimantan in Indonesia and Sabah, Sarawak and Labuan in Malaysia and Mindanao in the Philippines. Coverage may, however, be modified. For instance, Southern Palawan of the Philippines showed strong interest in the EAGA because it complements Palawan’s existing geographic and cultural ties with Sabah and Sarawak in Eastern Malaysia. Priority Areas of Cooperation At the Inaugural Ministerial Meeting in March 1994, the initial priority areas identified for cooperation include the following: Expansion of Air Linkages. A regional air services system will be established to promote, develop and enhance trade in the growth area with Bandar Seri Begawan as the center. The national airline of Brunei has already been granted landing rights in the cities of Davao, Zamboanga, General Santos, and Puerto Princesa of the Philippines. Direct flights have already been established between Manado and Davao and between Labuan and Zamboanga. Joint Tourism Development. There will be a separate study leading to a Joint Tourism Master Plan based on the tourism development plan of each country. An East ASEAN Tourism Workshop for the Growth Area has been completed in Labuan, Malaysia. This activity will be spearheaded by the Malaysian Government. Expansion of the Fisheries Cooperation. The Philippines takes the lead in this activity and a meeting of public and private sector representatives of the fisheries sector from the EAGA has been completed which assessed the status of the industry and discussed possible joint ventures. Expansion of Sea Linkages, Transport and Shipping Services. An existing shipping system connects General Santos City of the Philippines and Manado of Indonesia primarily to service the tuna industry. A Philippine shipping line is now plying the Zamboanga-Sandakan route, offering both passenger and cargo services. Indonesia, being the lead country for this activity, had organized a meeting in Balikpapan between port and shipping authorities and the private sector participating countries which discussed potential activities, including the possibility of a shipping route with Zamboanga and Bandar Seri Begawan as additional ports. It is worthy to mention at this juncture that the BIMP-EAGA initiative in Mindanao is facilitated by the a pool of able Technical and Administrative Secretariat of the Mindanao Economic Development Council (MEDCo) based in Davao City. 11 Decentralized Cities in Mindanao Under the 1991 Local Government Code The Cory Aquino Government, then, was interested in decentralization as a centerpiece of public administration for a number of reasons – political as well as economic. In particular, the administration saw three major reasons for devolution (LDAP, 1990) 30/: (1) greater share of resources from the national government to the local government units; (2) increased revenue mobilization and generation; and (3) local participation for improved services. The current Local Code is a detailed legal instrument for local autonomy as defined in the 1987 Philippine Constitution. Its immediate greatest impact was the creation of an “enabling environment” through which the local government units (LGUs) could be self-governing. In the words of President Corazon C. Aquino (1991)31/, the enactment of the Code was "... high point in our efforts as a people to strengthen democracy and attain a sustainable development. The new law lays down the policies and seeks to institutionalize democracy at the local level. It hopes, therefore, to complete the initial process of empowering our people through direct participation in the affairs of government, by allowing them the widest space to decide, initiate, and innovate". The Code required devolution of many personnel from the national agencies and their corresponding authorities to the LGUs. This also involved stripping the national agencies of their “oversight” and control roles. However, national agencies retained the duty to assist LGUs in technical and procedural matters until such time that the LGUs could become self-sufficient. By unleashing energies and initiatives at the front lines -- where people are -local autonomy is expected to bring about greater productivity, and broaden access to resources and opportunities. Time will tell what the strategic impact of the Code will be. Indeed, time will tell as the succeeding summary highlights the report from the seven (7) rapid field appraisals (RFAs) on devolution (ARD, 1997)32/: The First RFA of July 1992 saw local government officials adopting a “wait-and-see” attitude. The Second RFA of January 1993 found local government officials beginning to move forward on Code implementation, with national government agencies responding. The Third RFA of September 1993 had problems in the devolution of personnel being solved, and the Internal Revenue Allotment (IRA) system beginning to function. The Fourth RFA of June 1994 demonstrated increased momentum on the part of the LGUs as they reaped the fruits of experimentation. The Fifth RFA of June 1995 found increased local resource mobilization, and improved service delivery. However, national government agencies (NGAs) had not pro-actively filed new roles after devolution was accomplished. The Sixth RFA of May 1996 demonstrated incredible diversity. Within this diversity, the decentralization process was diffused and deepened. LGU management was more pro-active and developmental, and local governments and communities were insisting on more local autonomy. The Seventh RFA of August 1997 revealed innovation, quality and relevance at the local level. Governance in the Philippines is being redefined at the local level. The Code provides an enabling environment that allows experimentation, participation, and differentiated service delivery throughout the country. Despite the transition difficulties, encountered at the beginning of Codal implementation, the redefinition of governance has allowed LGUs to better serve their communities. A new participatory style of leadership is emerging. Decentralization through devolution under the 1991 Local Code has been an overall success. 12 Cities As Decentralized Local Government Units Indeed, the setting up of decentralized form of governance can be considered a landmark achievement in the Cory Aquino and Ramos administration. In a country where the urban focus tends to get confused and biased in favor of large conglomerations such as Metropolitan Manila, the empowerment of lower level units will definitely improve policies and programs on more realistic and attainable grounds. Constituted by law, local governments are endowed with political and corporate powers that allow substantial control over local affairs and representation of the inhabitants of their territories. For its part, “cities” constitute a separate tier in the four-tiered local government hierarchy of the country. Along with barangays, municipalities, and provinces, they form the Philippine local government system. A city is classified as either “highly urbanized” or component. Highly urbanized cities are completely independent of the province and exercise total control of their own resources. They are required to have a minimum population of 200 thousand and the latest annual income of P50 million. Cities which do not meet these requirements are classified as “component”. Of the fifteen highly urbanized cities, six or 40 per cent are located in Mindanao. These include the cities of: Davao, General Santos, Cagayan de Oro, Butuan, Zamboanga, and Iligan. The Fiscal Opportunities for the Cities Under the Current Local Code Among the local government units, cities are in the best position to go beyond basic needs and undertake development projects because of their broader revenue base and revenue authority. They can levy all impositions by municipalities and provinces; however, they can only exceed the maximum rates allowed for the provinces and municipalities by up to 50 per cent except in the case of professional and amusement taxes. Cities have the power to raise and use their own income which include taxes, fees, and charges. The biggest revenues are usually derived from real property tax and business taxes. One of the newest local sources under the Local Code is the community tax, replacing the old national residence tax., which has to be paid by every inhabitant of eighteen years of age and over who is regularly employed on a wage or salary basis, or who is engaged in business or an occupation, or who owns real estate of an assessed value of P1,000 or more, or who is required to file an income tax return. Fees and charges come from public utilities and enterprises owned, operated, and maintained by cities within their jurisdictions. Aside from locally generated revenues, local government units are entitled to allotments coming from national internal revenue collections based on the third preceding fiscal year, computed at a maximum rate of 40 per cent by the third year of the effectivity of the 1991 Local Code. The shares are allocated by type or level of the local government unit in the following manner: provinces – 23 per cent; cities – 23 per cent; municipalities – 34 per cent; and barangays -- 20 per cent. The allocation formula includes: population (50 per cent); land area (25 per cent); and equal sharing (25 per cent). Local government units also have a share in the proceeds derived from the utilization and development of the national wealth within their respective areas. These include shares from mining taxes, royalties, forestry and fishery charges, and other surcharges, interests, or fines in any co-production, joint venture, or production-sharing agreement. Any government agency or government-owned or controlled corporation (GOCC) engaged in the utilization and development of the national wealth is also required to share its proceeds with the local government units concerned (Panganiban, 1994)33/. 13 Conclusion The implications of globalization outlined in Part 2 of this paper called our attention to at least three sets of challenges: (1) the breakdown of national regulatory power is likely to lead to the devolution of government functions to local government units; thus, there will be intensification of competition among regions and localities which are likely to expand spatial inequalities; (2) the increase of the mobility of capital and business activities will change the comparative advantage for industrial location as production space for domestic firms expand across national boundaries; therefore, it will be a challenging task for local government units to maintain the stability and self-sufficiency of their local economies in the global economy; and (3) the spread of the capitalist mode of production has also significant impact on the changes of regional and local development because it will change the spatial structure of economic activities such as in production, financing, R&D, management and the like which will require a different set of location factors of production. High-tech and information industries require not only advanced communication and information facilities and specialized services but also high quality residential environments. Judging not only from the spatial and urbanization trends in Mindanao, but more so from its initiative in cross-border cooperation via the BIMP-EAGA, it is with optimism that the cities of Mindanao are poised to face up-front the forces of globalization in the 21st century. The issue concerning intensification of inter-regional competition and inequalities can be addressed by the strengthening of urban-rural linkages as demonstrated by the key development strategies as well as the three substrategies adopted in the medium-term development plan. The implementation of the People’s Industrial Enterprises (PIEs) found parallel trends from the successful British “new towns experiences” and Japan’s “technopolis experiences” (Masser, 1995)34/. For practical purposes, however, it is best to be reminded of Friedman’s attempt to settle the issue of inequalities in the context of “balance growth” as there can never be an absolute balance in quantitative terms across space. Our general agreement with this stance brings us to postmodern theory in politics and planning. As Watson and Gibson (1995: 262-3)35/ emphasized, post-modern politics suggests many possibilities. It defines an end to simplistic notions of class, alliances, or urban social movements. It also defines an end to a politics which assumes linearity of progress or the inevitability of revolution. No one political solution will emerge which will be universally just. Power will be continually contested, and new and different strategic alliances will emerge at each point of resistance. Postmodern politics recognizes that there never can be one solution which will benefit all people in all places for all time. Such an ideal can only lead to disappointment. Rather, postmodern politics allows for – both marginal and mainstream -- recognizing that victories are only ever partial, temporary and contested. At the very least, what postmodern theory has done is to open up a plethora of ways of thinking and acting politically. The challenges brought about by localization forces accompanying globalization could be contained by the local governments of Mindanao cities as substantiated by the overall success in the implementation of the current Local Code – at least during the first six years of political decentralization. Again, following postmodern theory, this “success story” narrative may be contested. Therefore, the complexity of globalization and localization forces should continue to position the national government -- but more strongly the regional and local government units in Mindanao regions of the Philippines to sustain exploration of progressive and rational spatial development strategies and policies that combine the concerns for the economic, social, political, environmental, and cultural dimensions of urbanization. 14 Notes 1/ Paper virtually presented to the International Conference on Learning and Community Enrichment (ICOLACE 2010) held on July 27-29, 2010 at Traders Hotel, Singapore. 2/ Professor VI, College of Governance, Business and Economics (CGBE) and Director, Mindanao Center for Policy Studies (MCPS), University of Southeastern Philippines, Obrero Campus, Davao City, PHILIPPINES. 3/ Lee, G and Kim, Y (1995). Globalization and Regional Development In Southeast Asia and Pacific Rim (Seoul, Korea: Korean Research Institute for Human Settlements) 4/ Dubford, Mick and Kafkalas, Grigoris(1992). 'The Global-Local Interplay, Corporate Geographies and Spatial Development Strategies in Europe' in Dunford, M & Kafkalas, G. (eds.), Cities and Regions in the New Europe (London: Belhaven Press).' 5/ Swyngedouw, Erik (1992). 'The Mammon Quest: Globalisation, Interspatial Competition and the Monetary Order, The Construction of New Scales in Dunford, M. & Kafkalas, G. (eds.) Cities and Regions in the New Europe (London: Belhaven Press). 6/ Amin, Ash (1992). 'Big Firms Versus the Regions in the Single European Market' in Dunbford, M. & Kafkalas, G. (eds.) Cities and Regions in the New Europe (London: Belhaven Press). 7/ Leborgne, _D. and Lipietz, E. 1988). 'New Technologies, New Modes of Regulation: Some Spatial Implications, Environment and Planning: Society and Space, Vol. 6,. 8/ Friedmann, John (1978). Regional Policy: Readings in Theory and Application (Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of technology Press) 9/ Antipolo, Sophremiano (1989). 'Strengthening Urban-Rural Linkages As Alternative Strategy for Regional Development: A Survey' Internal Working Paper (Washington, D.C: Urban Division, The World Bank). This working paper was later recast and published as a book entitled: Strengthening Rural-Urban Linkages An An Alternative Strategy for Regional Development: An International Survey and Synthesis With Philippine Component (Davao City: Mindanao Center for Policy Studies, University of Southeastern Philippines). 10/ Lee, Kyu Sik (1989). The Location of Jobs In A Developing Metropolis: Patterns of Growth In Bogota and Cali, Colombia (New York: Oxford University Press). 11/ Ownes, Edgar and Shaw, R. (1976). Development Reconsidered: Bridging the Gap Between Government and People (Lexington, MA: Lexington Publishing) 12/ Gibb, Arthur Jr. (1984). 'tertiary Urbanization: The Agricultural Market center As A Consumption Related Phenomenon' in Regional Development Dialogue (Nagoya, Japan: United Nations Centre for Regional Development) 13/ Friedmann, John (1978). Regional Policy: Readings In Theory and Application (Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press) 14/ “People Power at EDSA” refers to the 1986 historic, peaceful, and bloodless revolution mounted by the Filipino people against then President Ferdinand E. Marcos who ruled the Philippine for more than two decades – generally under martial law. EDSA refers to Epifanio de los Santos Avenue -- the major highway in Metro Manila linking its northern and southern suburbs. 15/ NEDA Board (2006). The Medium-Term Philippine Development Plan, 2006-2010 (Manila: National Economic and Development Authority). 16/ Paderanga, Cayetano, Jr. And Pernia, E. (1979). ‘Economic Policies and Spatial and Urban Development: The Philippine Experience’ in Regional Development Dialogue, Vol 5, 1979 (Nagoya, Japan: United Nations Centre for Regional Development) 17/ The policy shifts refer to free trade period under the Underwood-Simmons Act during the Colonial period in 1900-1939; the Import Substitution Period in 1948-67; and the Regional Awareness Period in 1970s onwards. 18/ Doeppers, D. (1972). ‘Development of Philippine Cities Before the 1900’ in Young, Y. And Lo, C. (eds.) Changing Southeast asian Cities: Readings In Urbanization (singapore: Oxford University Press). 19/ See Sobrepena, Aniceto in Lee, G.Y and Kim, Y.W (1995) Globalization and Regional Development in Southeast Asia and Pacific Rim (Seoul: Korean Research Institute in Human Settlements) 20/ Braudel, F. (1984). The Perspective of the World (London: Fontana Publishing). 21/ Sassen, Saskia. (1986). ‘New York City: (London: Blackwell Publishing) 22/ Ross, R. et. al. (1993). ‘Global Cities and Global Classes: The Peripheralization of Labor In New York City in Review , New York. 23/ King, A. (1990). Publishing). 24/ Friedmann, J. (1986). ‘The World City Hypothesis’ in Development and Change (London: Blackwell Publishing) Economic Restructuring and Immigration’ in Global Cities: Post-Imperialism and the Internationalization of London 15 Development Change (London: Blackwell 25/ National Economic and Development Authority (1993). Mindanao Development Framework Plan, 1993-1998 City: Mindanao Economic Development Council). 26/ Pernia, Ernesto et. al. (1994). Spatial Development, Urbanization and Migration Patterns in the Philippines (Makati City: Philippine Institute for Development Studies) 27/ Disaggregated data for the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM) is not yet available; hence, it is still covered by Regions IX and XII. 28/ Sobrepena, Aniceto (1994). Regional Cross-Border Cooperation: A New Dimension in Regional Planning City: Philippine Institute for Development Studies) 29/ Sobrepena, Aniceto (1995). 'Regional Cross-Border Cooperation: Towards Higher Forms of Economic Integration' in Lee, Gun Young and Kim, Yong Woong (eds.) Globalization and Regional Development in Southeast Asia and Pacific Rim (Seoul: Korean Research Institute for Human Settlements) 30/ Local Development Assistance Program (1990). LDAP Policy Paper on Decentralization (Manila: National Economic and Development Authority) 31/ Aquino, Corazon (1991). 'Presidential Message' in Congress of the Philippines Local Government Code of 1991: A Primer (Manila: Congress of the Philippines). 32/ Associates in Rural Development (1997). 'Synopsis of Findings' in Report from the First to Seventh Rapid Field Appraisals on Decentralization and Local Development (Makati City: Associates in Rural Development, Inc.) 33/ Panganiban, Elena (1994). ‘Cities As Decentralized Institutions for Urban Development In The Philippines’ in Regional Development Dialogue, Vol. 15, No. 1, Summer 1994 (Nagoya: United Nations Centre for Regional Development. 34/ Masser, Ian (1995). 'Urban and Regional Strategies In An Era of Global Competition' in Lee, G.Y. & Kim, Y.W. (eds.) in Globalization and Regional Development in Southeast Asia and Pacific Rim (Seoul: Korean Research Institute for Human Settlements) 35/ Watson, Sophie and Gibson, Katherine (1995). 'Postmodern Politics and Planning: A Postscript' in Watson, S. & Gibson, K. (eds.) Postmodern Cities and Spaces (Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing) -oOo- 16 (Davao (Makati